This report is part of the Elections & Violence in Mexico Project

Data production and analysis are coordinated by María Teresa Martínez Trujillo

Click here to read our Summary of Data on Political & Electoral Violence in Mexico, 2020-2021

Click here to go back to the Project’s main page

Introduction

Elections are probably the most revealing ritual about a democracy. What are the conditions under which candidates persuade the electorate? How do the latter exercise their right to vote? What are the campaigns like? And, eventually, what do victories and defeats go? These are the questions that define not only democracy, but also the political game itself.

In Mexico, the entire process involves violence. If incidents occur during every electoral cycle, it means that they cannot be analyzed apart from the complexity of the political life itself: they are part of it.

In this report, we analyze the 2020-2021 electoral period. This garnered special attention both inside and outside the country. It was the largest election in Mexican history, and multiple incidences of violence involving candidates were recorded. This violence manifested itself in the form of threats, intimidation, and other violent acts, including homicide.

In a few words, violence and coercion appear to be key factors in the Mexican democracy. However, what do we know about the political-electoral violence that occurred during the recent elections? What type of incidents occurred and how? What is the profile of the victims and the aggressors? This report responds to these and other questions based on our Noria MXAC Database on political and electoral violence Mexico, 2021.

In order to reformulate these questions, and review certain recurring narratives, we have undertaken this project not only to count the number of incidents but also lay the foundations for a series of explanations that can be developed through the available data.

In our Report, the term “political-electoral violence” covers any act of coercion that is committed against political actors or those who play a role in this arena.

The report is divided into four sections.

In the first section, we discuss the ways in which political-electoral violence in Mexico is measured. We highlight the scope and limits of the data available. We also describe the creation of the aforementioned Noria Database in order to provide transparency about our methodology, while outlining its analytical limitations.

In the second section, we analyze the incidences of political and electoral violence reported by the local and national press, which were compiled and systemized by the Noria Program for Mexico and Central America (herein referred to as MXAC). In this section, we discuss what the data reveals about electoral violence, in addition to relevant blind spots, anticipating how they could be mitigated in the future.

The third section focuses on the case study of the state of Veracruz, in which the highest number of incidents were recorded during the 2020-2021 period. We explore some clues as to what happened there.

Finally, in the fourth section, we look at the incidents reported on election day, June 6, 2021. Even though this is a summarized version of events, given the magnitude of the election, it is important to analyze what type of incidents occurred, what we know about the perpetrators, and discuss the implications has on the act of voting, and the aftermath for current administrations.

Counting, Measuring, Explaining. Three ways to better understand the phenomenon of political-electoral violence.

What do we investigate?

“The most violent election ever” is a label that tends to be handed down from one electoral cycle to another, both in terms of expectations surrounding the election process and its conclusion. However, how do we measure and decree that one election is more violent than another? What parameters do we use to define the level of political violence that occurs during an electoral process? How, in fact, do we categorize political and/or electoral violence?

The first step in finding an answer to this question is to define – and basically decide on – what we are referring to when we talk about political-electoral violence. In our report, the term covers any act of violence that is committed against political actors or those who play a role in this arena. Generally speaking, in Mexico, this concept encompasses incidents that occur during electoral periods, which is why there is a trend of focusing mainly on candidates standing for election who suffer any form of aggression, especially homicide.

Expanding the notion of violence beyond the act of homicide enables to analyze other forms of coercion, such as threats or intimidation, which have crucial effects on political life and which are generally underestimated or overlooked.

Yet, this does not include incidents that occur whilst they are in office, or when their candidacies are being defined, both of which are situations where there may be tensions between actors who are competing against or facing one another. Furthermore, expanding the notion of violence beyond the act of homicide enables to analyze other forms of coercion, such as threats or intimidation, which have crucial effects on political life and which are generally underestimated or overlooked.

In our work, we take into consideration acts of violence that are committed against actors who are in office, not just candidates standing for office. Furthermore, in order to ensure the discussion transcends the electoral period, given that the purpose of this report is to reflect on what happened during the campaign, we will use data from the period comprising September 2020 to June 6, 2021, election day, which is formally known as the electoral process.

How, and where do we investigate?

Once we have a better idea about what we want to explore, the challenge lies in actually investigating it. The most basic approximation is counting, i.e., adding the number of cases of aggressions, threats, attacks, enforced disappearances, and homicides, among other forms of violence. To do so, we require a source of information that allows us to find cases of interest to study.

Court records, police files or sentencing documents should be the ideal source of information given that, in addition to compiling data about the number of cases, it is possible to find details about what actually happened. However, given the high levels of impunity in Mexico, very few cases end up in court, and the quality of the data depends on the ability of institutions to learn about the cases, first, and then document, register and, eventually, report them.

Furthermore, medical records could also be a valuable source. But these – if and when they exist – are limited to serious forms of aggression that require the intervention of medical, and even forensic, personnel. Then, they tend to overlook other forms of violence, such as threats or damages that are committed against the assets of political actors, for example.1

Almost 100% of the data available on political-electoral violence comes from press reports.

Then, the vast majority of it is compiled by private consulting firms, or centralized in non-accessible academic databases.

Then, official records (police files and/or medical records) are partially accessible through mechanisms that have been implemented to promote transparency. Compiling this data is an extensive documentary procedure, not to mention the series of requests that must be filed to access data that is still probably incomplete.2

This is why the major source of information used in Mexico to compile cases of political-electoral violence is the press, at both a national and local level.3 Although this is not a bad place to start, it is important to remember that not everything that happens in certain areas is then reported in a newspaper. Besides, the data published by the press and which, after a careful and systematic process, is converted into a database, is not exempt from replicating the bias with which the press compiles and reports on what has happened.

Because we work with press reports, we must not lose sight of the fact that the cases reported may say more about a media outlet’s coverage than it does about what is actually happening.

For example, one media outlet may run an editorial line that means that greater or lesser attention is paid to certain types of electoral violence, over-representing some practices, or even under-reporting others. On the other hand, if a violent act occurs in an area in which major media outlets do not have a correspondent, it is likely that this story will not go any further than local media outlets with low readership figures, if any record is actually made of said incident. In other words, to mobilize the data that comes from reviewing media outlets: 1) it is important to ensure the highest possible number of media outlets and types in the process, and; 2) we must not lose sight of the fact that the cases reported may say more about a media outlet’s coverage than it does about what is actually happening.

Finally, social networks may be of great help in order to diversify our sources of information about political violence, even posts that are made in real time. Information published on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter or that is shared via discussion groups on WhatsApp and other semi-private forms of collective communication can also be a privileged data. In these cases, digital ethnography techniques should be implemented4, allowing for the compilation of information, the development of mechanisms to filter unreliable data, and the overcoming of ethical dilemmas associated with the analysis of this type of data. This is a process that we have begun implementing at Noria-MXAC, one that is still in its infancy.

Counting is not measuring

Compiling the incidences of political-electoral violence does not mean that we understand the magnitude of the phenomenon. Besides, comparing totals from different years does not give us a clear idea of the seriousness of the issue nor does it enable us characterize it.

A series of questions then arise. Are there more attacks because there are more electoral seats at stake? Is there more political violence because there is more insecurity in general? In order to better understand these acts of violence, it is also necessary to understand the circumstances under which they occur.

For example, if we compare the figures from the COVID-19 pandemic, we can see that looking at the total number of people infected is not sufficient to fully understand the global situation; it is also necessary to know where the infections are happening, how many tests have been carried out, how many people have been hospitalized, and how many have survived. This is the same for incidences of violence: if we only look at the absolute numbers, we are left with a blurry and short-range overview of the situation, one that does not pave the way for the design of possible solutions.

This is why it is important to reaffirm the premise that counting is different from measuring. To achieve the latter, the compiling of incidents must be undertaken in conjunction with benchmarks that allow us to scale and characterize what is being observed. For example, the 101 politicians assassinated during the 2020-2021 electoral cycle (Noria-MXAC Database) could effectively be a higher number than those recorded during previous electoral processes. However, this does not necessarily reflect a worsening of the situation if, for example, we are dealing with an electoral process in which there is an increased number of candidacies or posts in play.

Counting is different from measuring. To achieve the latter, the compiling of incidents must be undertaken in conjunction with benchmarks that allow us to scale and characterize what is being observed.

Compiling the incidences of political-electoral violence does not mean that we understand the magnitude of the phenomenon. Besides, comparing totals from different years does not give us a clear idea of the seriousness of the issue nor does it enable us characterize it.

A series of questions then arise. Are there more attacks because there are more electoral seats at stake? Is there more political violence because there is more insecurity in general? In order to better understand these acts of violence, it is also necessary to understand the circumstances under which they occur. For example, if we compare the figures from the COVID-19 pandemic, we can see that looking at the total number of people infected is not sufficient to fully understand the global situation; it is also necessary to know where the infections are happening, how many tests have been carried out, how many people have been hospitalized, and how many have survived. This is the same for incidences of violence: if we only look at the absolute numbers, we are left with a blurry and short-range overview of the situation, one that does not pave the way for the design of possible solutions.

This is why it is important to reaffirm the premise that counting is different from measuring. To achieve the latter, the compiling of incidents must be undertaken in conjunction with benchmarks that allow us to scale and characterize what is being observed. For example, the 101 politicians assassinated during the 2020-2021 electoral cycle (Noria-MXAC Database) could effectively be a higher number than those recorded during previous electoral processes. However, this does not necessarily reflect a worsening of the situation if, for example, we are dealing with an electoral process in which there is an increased number of candidacies or seats in play.

Then, measuring the levels of political-electoral violence in Mexico implies going beyond merely adding up the details found in a newspaper article. What role do elements of the political and socio-economic context have on the occurrence of violence within the political game? Are rural areas more prone to the use of violence? How important is the role of partisanship in the strength or vulnerability of local politicians?

By adding context, we are able to operationalize different attributes (variables) that can surround, both in proximity and further afield, the incident. In addition to the efforts involved in compiling information – the latter being generally disperse, hard to make compatible, and almost always incomplete or inaccessible – this exercise involves no small number of discussions to define how to convert categories into more complex concepts.

For example, if our goal is to incorporate the variable of “partisanship” into our analysis, a logical step would be to consider the political party to which the victim of the violent incident belonged. However, this tells us little about the internal workings of a political party as it does not fully reflect whether being a member of the PAN or MORENA in one area is comparable to being so in a different one.

Then, party affiliations do not reflect whether a political party may have internal tensions in a certain area, or function in a more standardized manner in others – being affiliated to the PRI in Atlacomulco, (State of Mexico) does not mean the same as it does in Buenavista Tomatlán, Michoacán, or Tijuana, Baja California.

A violent incident is not just a number. Rather it equates to a proportion, a trend, a trajectory, a message, a practice, a relationship that may change over time. Hence, it may reveal or hide dynamics and behaviors that exceed and transcend specific situations.

Even more important, party labels can transform over time, even through alliances that would have been unthinkable in recent memory – the PRI-PAN-PRD alliance in 2021, for example. Nor does it indicate the candidate’s party loyalty or allegiance: the same surname can, over time, be linked to a number of different parties, as tends to happen in many regions throughout Mexico. As such, assuming that the workings of national political parties – or assuming what we know about them – are comparable to the workings at a local level is, at the very least, short-sighted.

Therefore, within the political game, a violent incident is not just a number. Rather it equates to a proportion, a trend, a trajectory, a message, a practice, a relationship that may change over time. Hence, it may reveal or hide dynamics and behaviors that exceed and transcend specific situations.

How to move from gathering data to explaining it?

Although the process of characterizing the perpetration of violent acts is one step beyond merely counting them, this does not yet imply that an explanation can be given. This means that the pedigree of the data can give us clues about how to analyze it, but its explanatory value depends on an interpretation that, once again, is not exempt from bias and propensities to replicate the stories of violence that we have already heard (narco-violence, for example).

In terms of political-electoral violence, preliminary measurements allow us to establish certain patterns regarding the perpetration of acts of violence against political players, but it does not necessarily reveal whether these are the result of a power struggle in the area between several groups capable of violence or whether these are efforts by criminal groups to control illegal markets or valuable sources of revenue from extortion.

The process of interpretation must incorporate an honest exercise that acknowledges the limits of the data and the disparity between what it tells us, and what it hides.

If we follow the dominant narrative that is used to explain violence in Mexico, it is likely that the number of incidents would be interpreted as another example of “organized crime groups striving to dominate the market”. However, if we incorporate the difficulty of distinguishing between one group of perpetrators from another based on their practices, the extent to which they cooperate with one another, how frequent their confrontations are, and how frequently the line between legal and illegal becomes unclear, we are able to better understand that the explanation surrounding this phenomenon must begin by compiling data.

Yet, said explanation will not be fully formed during this stage. This is when the process of interpretation must incorporate an honest exercise that acknowledges the limits of the data and the disparity between what it tells us, and what it hides; and what we could observe from a prolonged fieldwork, combined with data collection, production, and analysis.

Our Project, and the Creation of the Noria MXAC Database

The Noria-MXAC Database on political and electoral violence in Mexico-2021, is based on a wide-ranging and systematic review of national and local newspapers. Given the restrictions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, during this preliminary stage we compiled incidents only from those media outlets that are available online. However, the design of the database itself allows us to add cases and variables that will serve in the future, when we are able to return to newspaper libraries and archives.

The methodology

With a focus on minimizing the bias in coverage that we have already discussed, the selection of the media outlets reviewed was not based on considerations stemming from their level of circulation or reputation as specialist media outlets or watchdogs. Instead, a state-level approach was used, searching for all possible media outlets in the state, given that, during the exploration stage, we noted that local newspapers frequently reported incidences of violence against politicians that did not make it into more widely recognized media outlets in each state and, much less, into the national press.

The national newspapers include: Reforma, El Universal, Animal Político, La Jornada, Milenio and El Economista, among others. In terms of local newspapers, we reviewed several renowned publications – such as Zeta or El Informador – but we also looked at other lesser known ones, which, however, offer wide-ranging coverage of violent incidents. Although it is true that ‘nota-roja’ newspapers no longer document violent incidents in a detailed manner, as occurred between 1920 and 19505 in some cases these media outlets reveal the most information about a certain incident.

If, as we have mentioned, the data extracted from the press may contain significant bias, why should we continue working on a database that is based on newspaper articles?

In the search for cases, a media consultation process was employed based on 4 groups of keywords: the first group referred to the type of incident; the second focused on the victim’s post; the third dealt with the state in question; and the fourth referred to the year.

As such, in the first group, searches were undertaken based on terms such as “assassination”, “attack”, “kidnapping”, “threat”. In the second group, words such as “mayor”, “municipal president”, “alderman”, “councilor”, “deputy”, “candidate”, “public official” and “politician” were used, in addition to variations such as “ex-public official” or “ex-mayor”. The third and fourth groups of key words corresponded to the 32 states in Mexico and, for this stage of the project, the years 2020 and 2021.

How can we mitigate the bias?

Once a case that could be integrated into the database had been found, all available information was registered regarding the what, the how and the when of the incident. Furthermore, data about both the victim’s profile and those deemed responsible for the act were also added.

We frequently found articles containing little information about the incident. Given that the database has been designed to extract the largest possible amount of data relating to the incident, searches focusing on an identified case were expanded, using the name of the victim or other details about the incident.

Once the data relating to the incident and the victim profile have been compiled, supplementary variables from other sources were fed into the database. These variables are divided into three groups: those relating to the victim, those relating to the town or area in which the incident occurred, and those relating to the electoral context. For example, while newspaper articles regularly include the victims’ party affiliations, historical information about mayors from the National Municipal Information Service has enabled us to establish whether the victim belonged to the party in power or to the opposition party. Furthermore, attempts were made to record part of the victim’s political career in order to determine if he or she had belonged to more than one party and, with regard to candidates, if he or she had been supported by a coalition.

In terms of variables relating to the town or area, using databases from institutions such as National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) and the Executive Committee of the National Public Security System (SESNSP), distinctions were made between urban and rural areas and those with the highest rates of homicide and extortion. In terms of the electoral context, historical election results and participation numbers were recorded. This data compilation allows us to pinpoint the incident within a wider spectrum.

If, as we have mentioned, the data extracted from the press may contain significant bias, why should we continue working on a database that is based on newspaper articles? It is true that any record involving violence, be it from official sources, media outlets or other sources, will be incomplete and ambiguous.6

However, some of these limitations can be mitigated by using other sources to bolster the data. Furthermore, warning about possible bias enables us to exercise greater caution when interpreting the data and drawing conclusions from it. This is why the following section explores patterns in political-electoral violence in the 2020-2021 cycle that can be extracted from the Noria-MXAC 2021 Database, taking into account the richness of the data, but also highlighting what this approach does not reveal.

Lessons learned and blind spots in the analysis of political-electoral violence (2020-2021)

The 2020-2021 electoral cycle was considered to be the largest in history given the notable growth in voters and the 21,000 elected posts in play.

What do we know about the political-electoral violence that occurred during these elections?

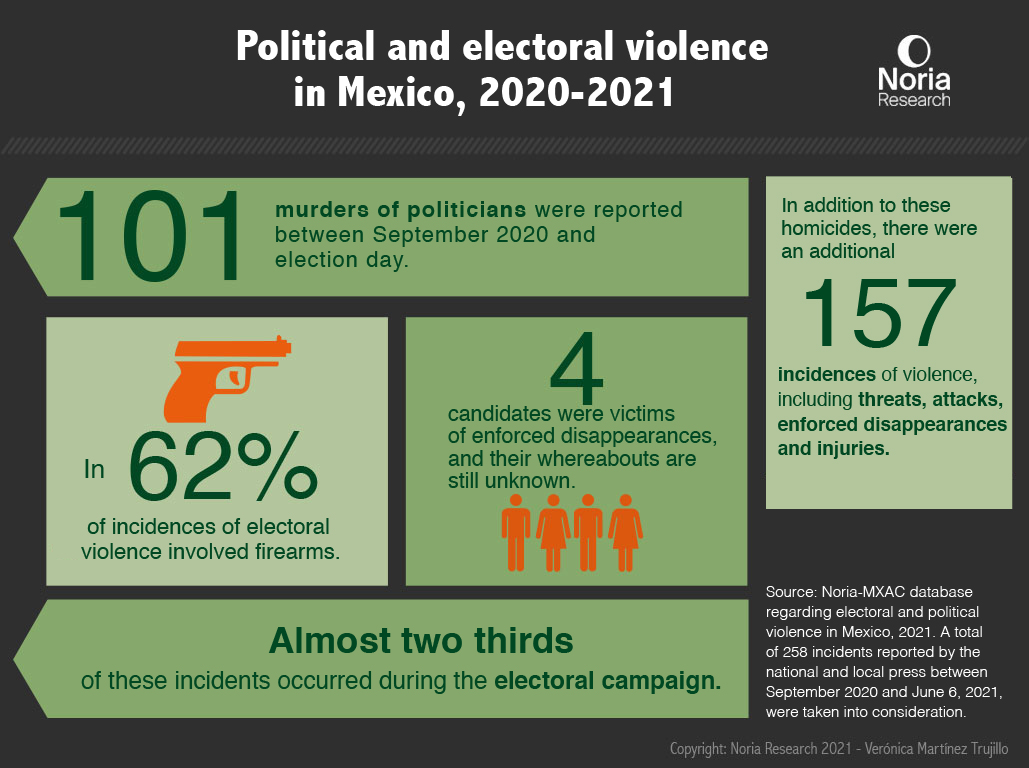

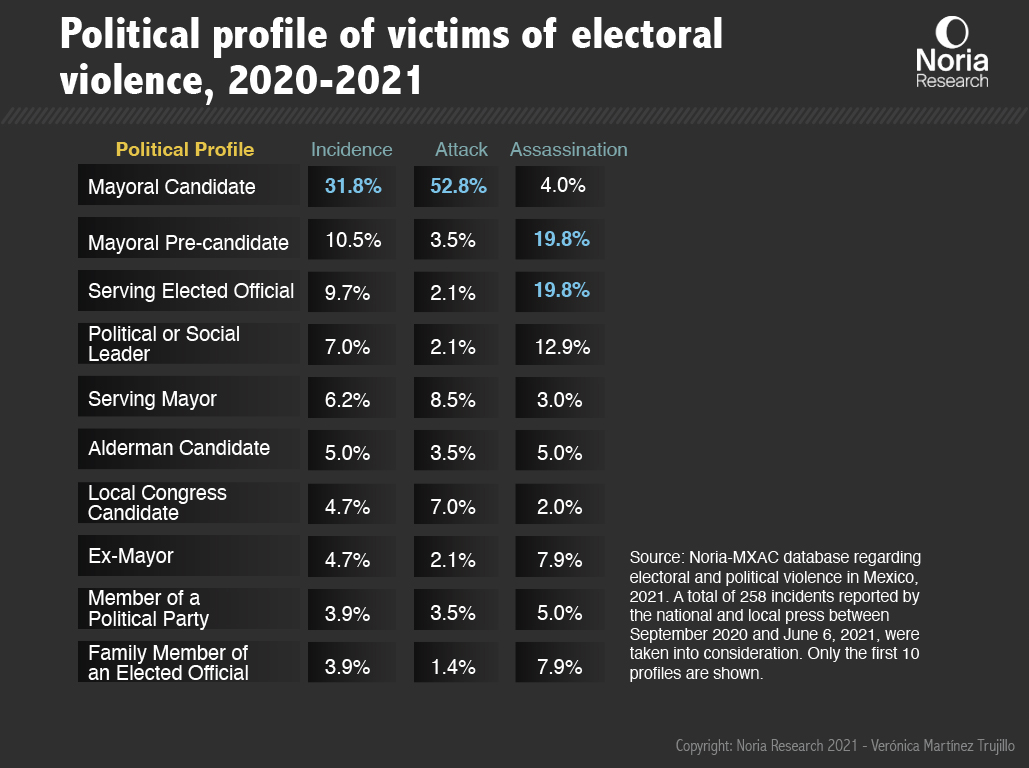

According to the Noria-MXAC Database on Electoral-Political Violence, 2021, from September 2020, when the electoral period began, and up until June 6, the day of the election, 258 incidences of violence against politicians were registered. As shown in Figure 1, of this number, 55% were attacks (142 cases), i.e., threats, shootings or attacks on politicians that did not end in the homicide of the person involved, while 39.1% of incidents were assassinations (101 cases).

It is important to take into consideration the fact that 58% of the victims of incidences of violence are pre-candidates, aspiring candidates or candidates for an elected post. On the one hand, this shows that candidacies, in terms of the processes involved in reshuffling political power, become spaces which outside interest seek to control through violence. On the other hand, it is noteworthy how, during an electoral process, violent practices are not limited to candidates, but they also focus on serving and ex-government officials.

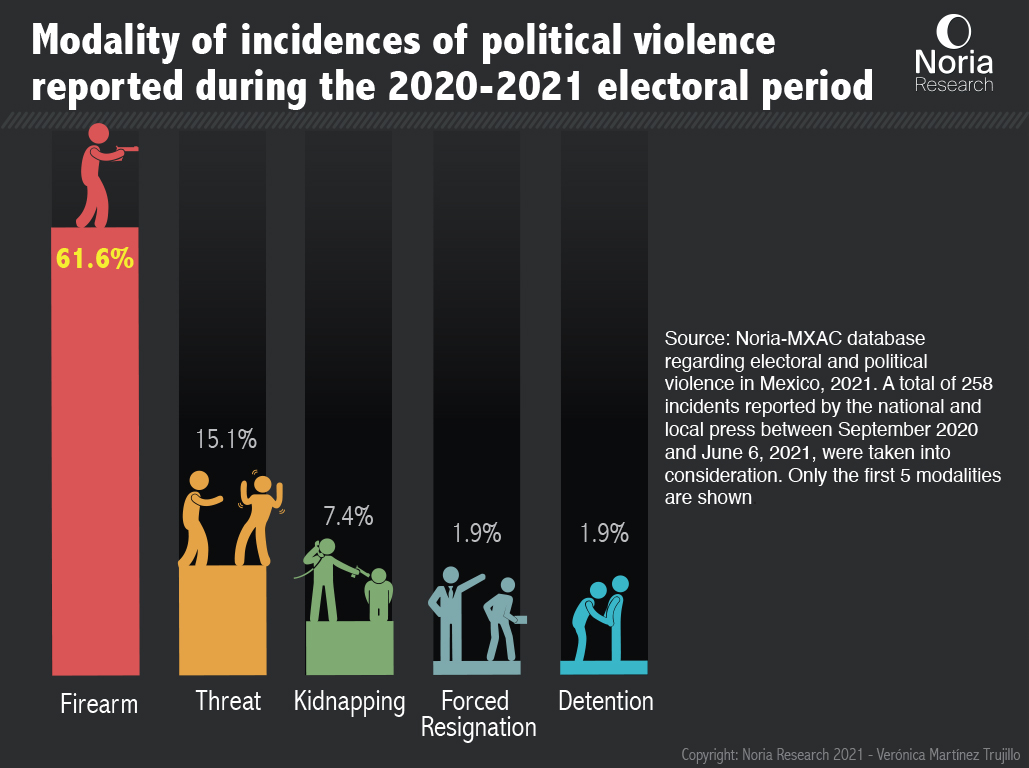

However, assassinations, as the most visible act of violence, should not overshadow the other forms of violence that abound, and which lead to a threatening atmosphere for candidates and other local politicians. In fact, one of the key elements in understanding this phenomenon has to do with the wide-ranging availability of firearms among potentially violent players. According to the data compiled, a firearm was used in 61.6% of the incidents. Furthermore, there are threats, kidnappings and other forms of violence in which the line between an attack and a homicide can be crossed with relative ease.

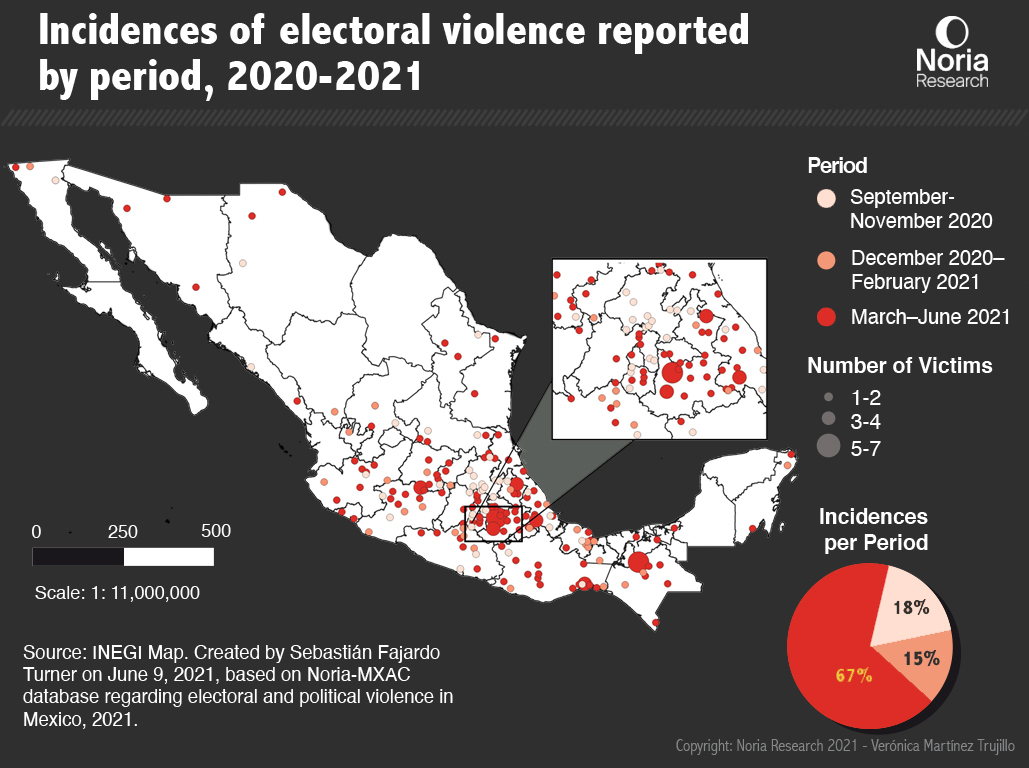

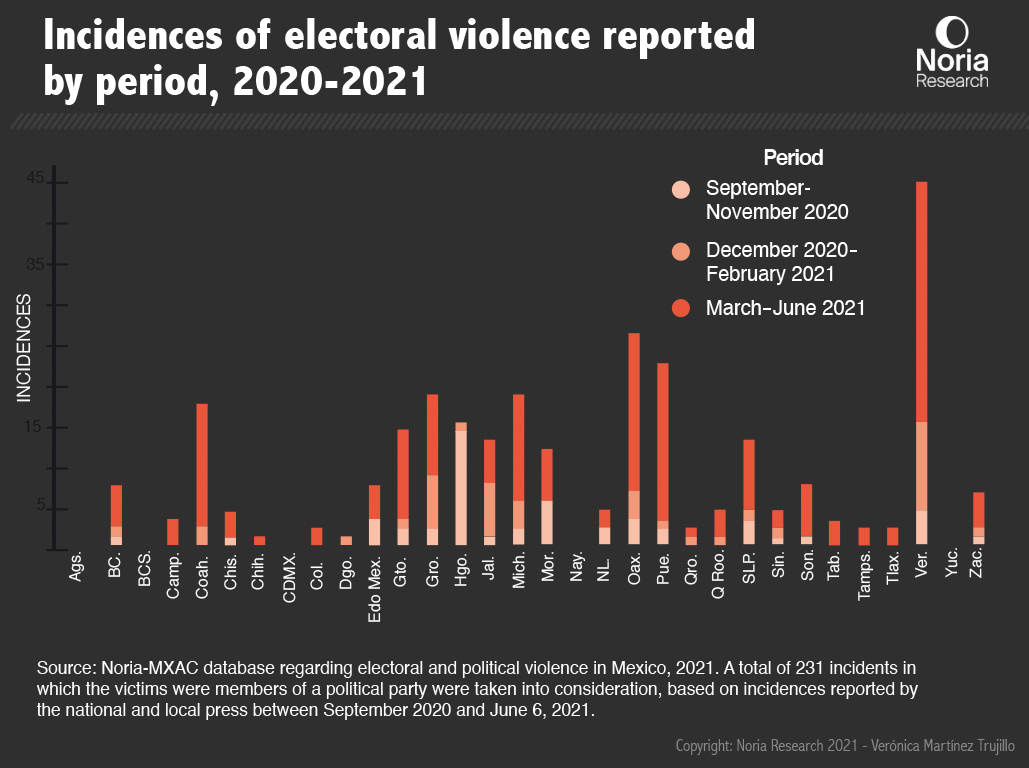

Incidences of political-electoral violence occur especially during the campaign and pre-campaign periods (Figure 3). In fact, as shown in Figure 4, between March and June 2021, 67% of the incidences of violence occurred. This period saw a higher number of victims compared to the earlier stages of the electoral cycle. This pattern is replicated in almost every single state, with the exception of Hidalgo, in which the vast majority of the incidences occurred between September and November 2020, i.e., the beginning of the electoral cycle.

Despite the fact that based on the data it is complicated to establish an explanation regarding the rate of incidences, it is important to relate them to other variables within the electoral context – for example, the level of competition present in the election – in order to determine if the ‘closer’ races could be more susceptible to incidences of violence, or even if leading candidates are particularly vulnerable. To do so, as we have mentioned previously, the database of incidents must be supplemented with data that is not always available. In the example given, this hypothesis could be proven through local voting polls linked to data from the incidence of violence that has been compiled in our database.

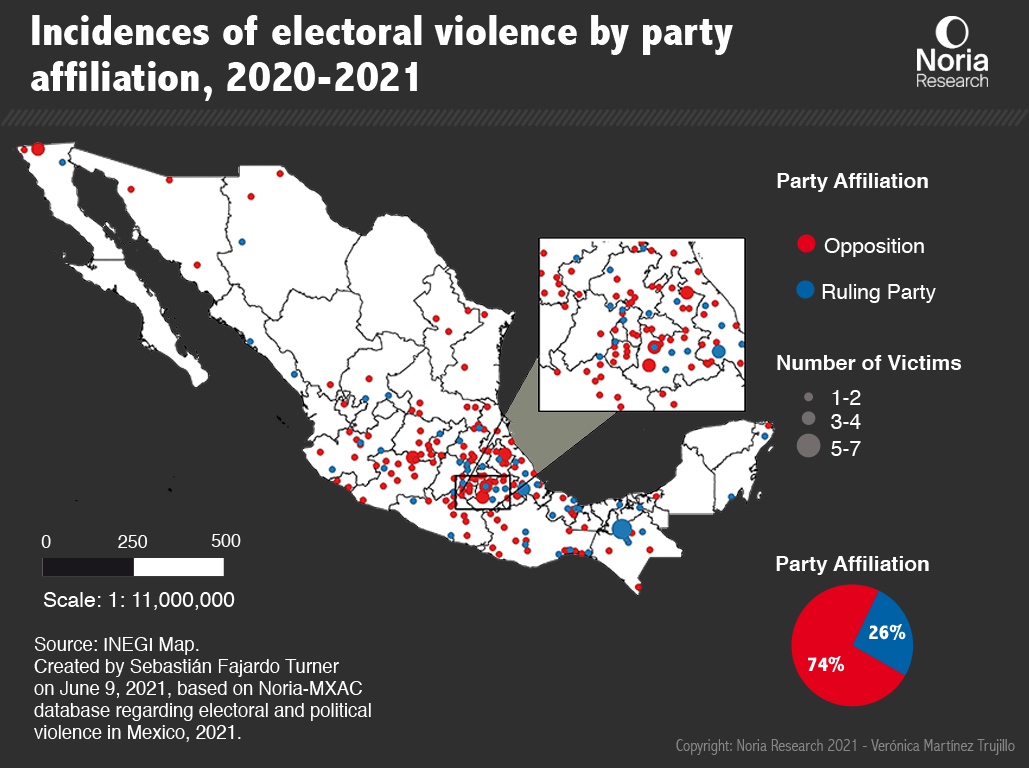

Regarding the geographical distribution of these incidents, it is noteworthy that they are concentrated in the central and western areas of the country, in addition to along the Gulf of Mexico. By contrast, incidents in the north of the country appear to be less frequent. For example, the six border states only recorded 24 of the total 258 incidents (9.3%). Although this could be explained by the underreporting of cases, it is important to take note of the fact that the northern border, which tends to be linked to patterns of daily violence attributable to drug trafficking, does not appear to be an area in which political-electoral violence has occurred frequently. Once again, it is worthwhile asking ourselves to what extent the geographical distribution of incidences of political-electoral violence is more closely related to political tensions, party influences , the composition of clientelistic networks, the influence of local chiefdoms (caciques), and patterns of political-criminal agreements, among other factors, rather than to the nature of illegal markets or the presence of ‘drug cartels’.

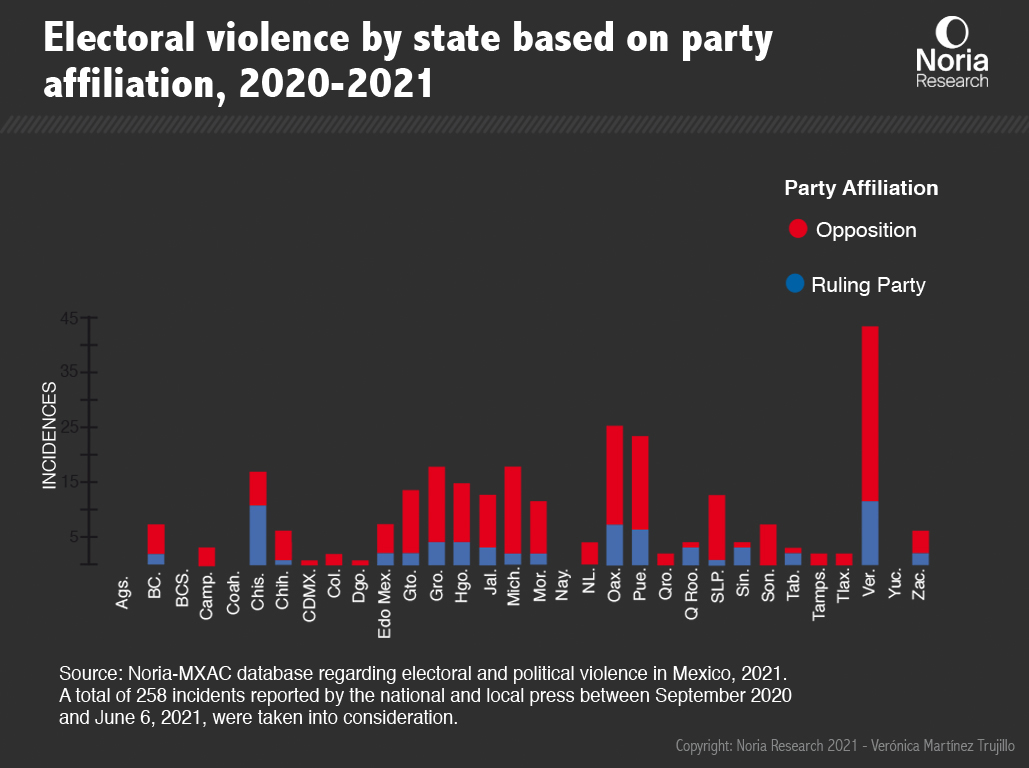

In fact, by analyzing the incidents by state, we note that 48% of recorded incidents are concentrated in five states: Veracruz, Oaxaca, Puebla, Guerrero and Michoacán.

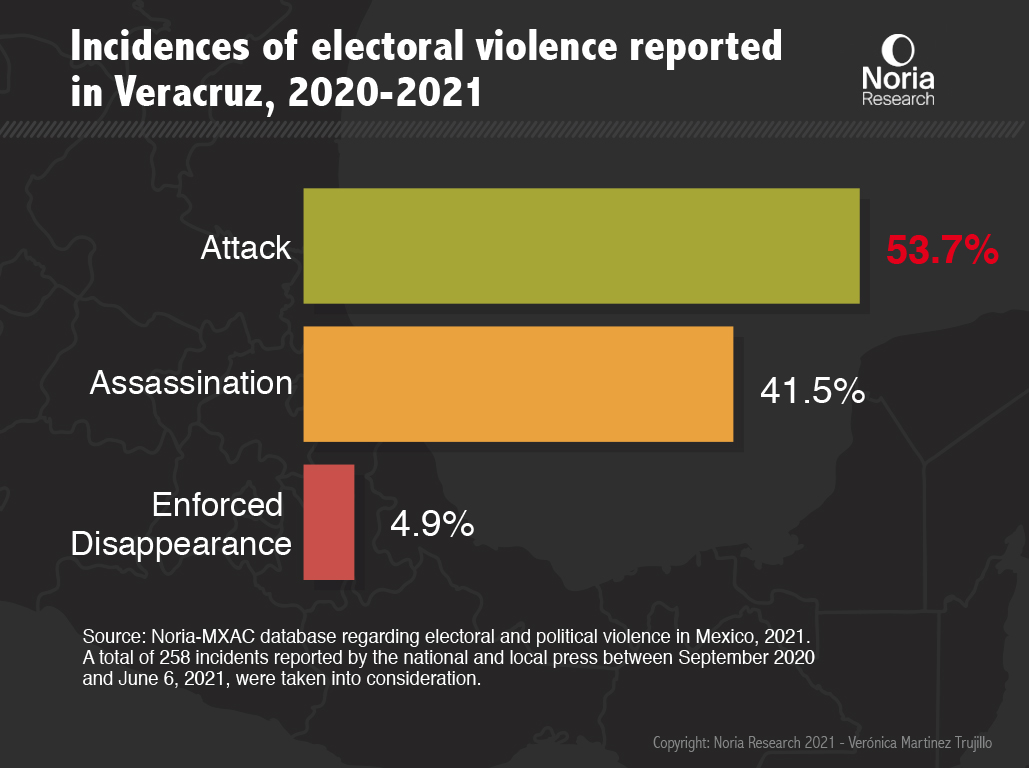

As shown below, Veracruz saw 15.9% of the recorded incidents, and it is also the state with the highest number of case of violence in the country. Of these, 41.5% were assassinations and 53.7% were attacks. In terms of Oaxaca and Puebla, there was a lower ratio of assassinations versus attacks. This means that it may appear that there are more episodes of violence, but these are less lethal than in states such as Chiapas, Jalisco, Guanajuato or Sonora, to mention but a few.

This list reveals, at least, two key traits of political violence. Firstly, it confirms that incidences of violence do not necessarily coincide with the most relevant so-called “drug-trafficking routes” or “locations”. Probably, the cases of Veracruz, Guerrero and Michoacán could be explained from this narrative – a point that we will come back to later – bur Oaxaca and Puebla, on the other hand, do not fit into this explanation. Secondly, the states with the highest number of incidents have a long history of political-electoral violence, predating the so-called “war on drug cartels” and the violence this caused. NORIA-MXAC believes that evidence of this can be found in the analysis of Hélène Combes into the violence perpetrated against members of the PRD at the beginning of the 1990’s, in addition to historical reports that we will be publishing in this space in the future.

The idea that “the country is worse than it was before” should be seriously discussed based on the available historiography, in addition to a discussion regarding the structural limitations that we have mentioned in our work: there is little – or no – reliable statistical data regarding political-electoral violence in Mexico prior to the 1990’s.

This analysis clearly shows that today’s violence comes from the past, not to mention that the idea that “the country is worse than it was before” should be seriously discussed based on the available historiography, in addition to a discussion regarding the structural limitations that we have mentioned in our work: there is little – or no – reliable statistical data regarding political-electoral violence in Mexico prior to the 1990’s. As such, the argument that the country was a peaceful one “before” is based mainly on the lack of data to confirm or critique this. In order to put an end to self-fulfilling prophecies, better data about these phenomena is urgently required.

What do we know about the victims of political-electoral violence?

The gender variable

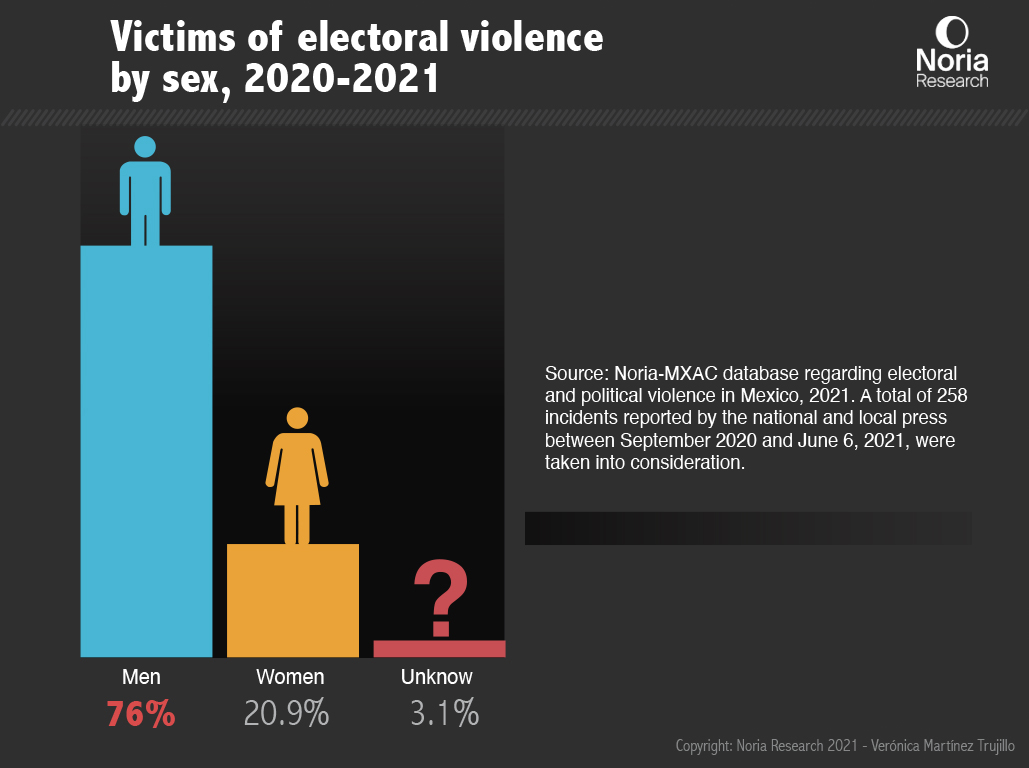

Based on the data we have compiled, the vast majority of victims of political-electoral violence are men (76%) while 20.9% are women.

At first glance, we can deduce that the pattern of violence during the electoral cycle replicates that of the violence observed out with political posts, given that men are the most frequent victim – in 8 out of every 10 deaths by homicide the victims are men (INEGI, 2019). However, this conclusion could overlook certain traits of violence against women that should be analyzed in more detail and that are not necessarily reported in media outlets, and, as a result, they do not make it into the database in question.

One of the most widespread forms of political violence against women lies in limiting the political spaces in which they can participate. The result of this structural violence is clear: women do not even aspire to stand as candidates.

For example, one of the most widespread forms of political violence against women lies in limiting the political spaces in which they can participate. The result of this structural violence is clear: women do not even aspire to stand as candidates. It has already been documented that, given that political parties continue to be patriarchal structures, measures such as the definition of parity quotas do not necessarily lead to equal access to political posts for women (Cerva Cerna, 2014), turning this into an unresolved matter that goes beyond the question of violence.

Furthermore, although the 2021 election was the first to see 10 out of 32 state congresses with a female majority, it is important to take a closer look at the processes of political violence to which the women who compete in this area are exposed to. For example, female government officials from the Department of Women in Oaxaca interviewed by María Teresa Martínez Trujillo7 stated that in certain municipalities governed by customs and traditions women have both a presence and a voice in their community assemblies. However, when it comes to voting (or being voted for) or the decision-making process, these female representatives are removed from the session. Moreover, the threats made against female candidates, both in rural and in urban areas, are aimed not only at them, but also their families (children, parents, siblings), using their role as mothers or carers – which are gender-based mandates – to make them vulnerable.

The female government officials interviewed in Oaxaca estimate that women involved in politics are progressively showing a greater awareness and propensity to report violence-based practices against women within the political game. If this observation is confirmed in other states over time, it is possible that, in the future, we will see an increase in the number of cases of political-electoral violence against women being reported, in addition to an increase in requests for protection. If this proves to be the case, once again, more detailed and comprehensive information will help distinguish between what can be classified as an increase in violence and what can be viewed as an increase in the number of reports and the response to a problem that tends to be minimized. In any case, political violence for reasons involving gender requires a much wider-ranging and accurate analysis.

Local scale: maximum vulnerability

The political profile of the victims, outlined in Figure 7, reveals that political-electoral violence is a phenomenon that exists mainly at a local level. In fact, only 3.5% of incidents involve federal government officials – members and ex-members of the Chamber of Deputies. Mayoral pre-candidates and candidates are those most affected. Furthermore, this pattern of victimization also includes other serving government officials, political leaders, local council candidates, or candidates for local congress.

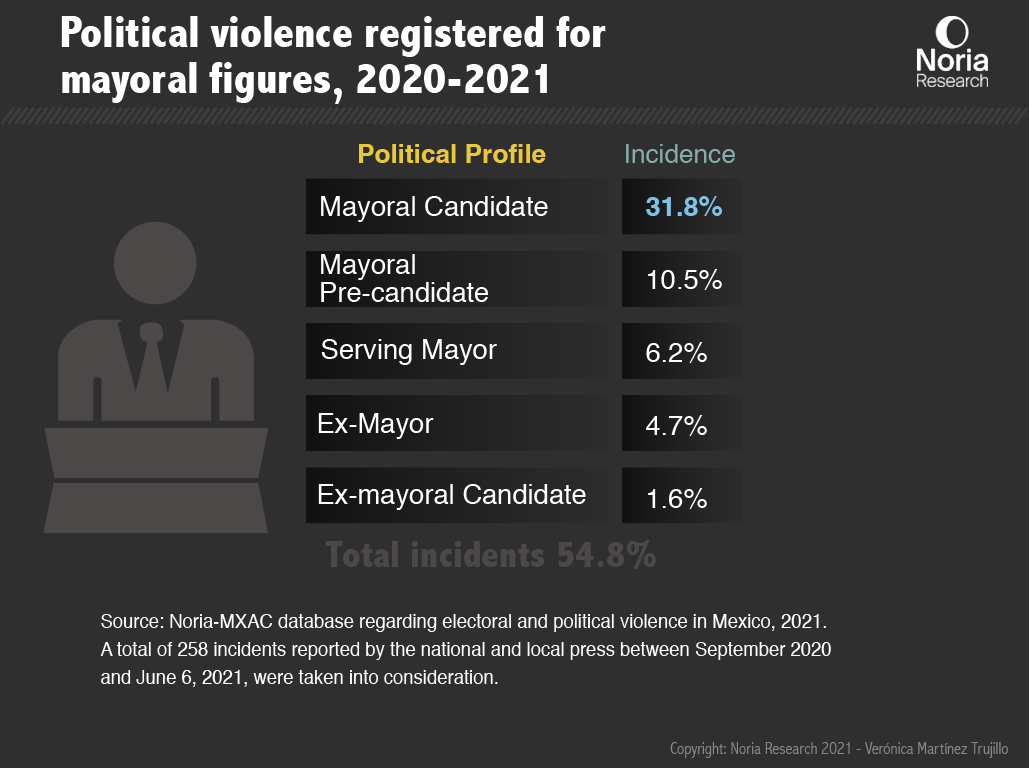

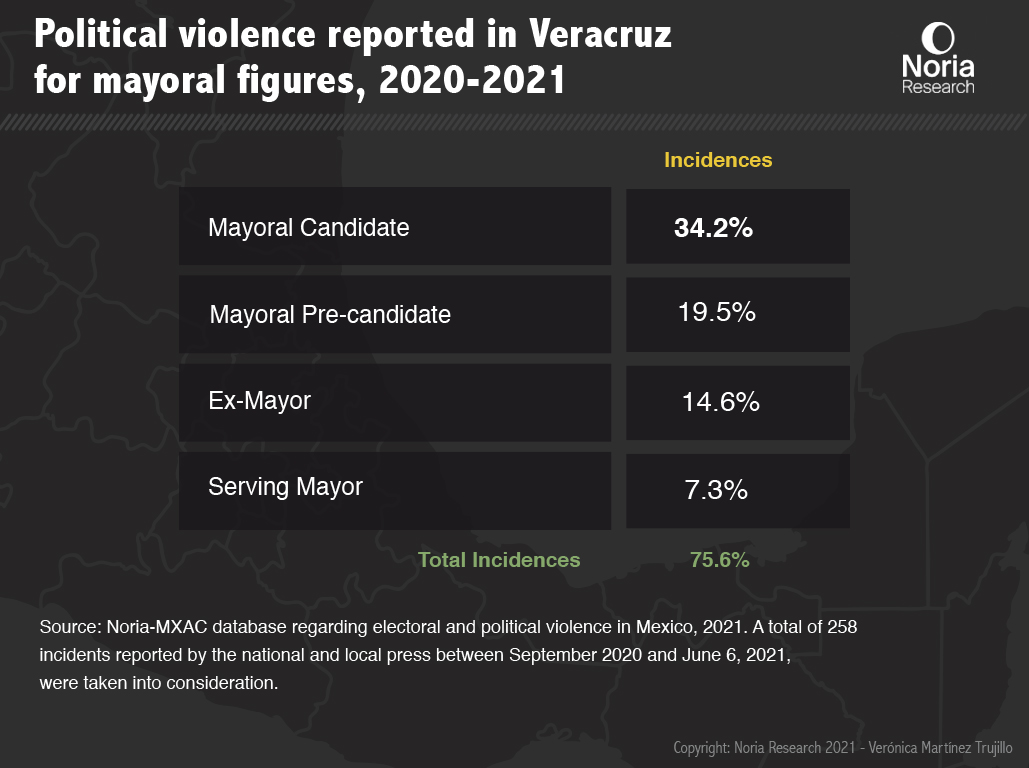

As such, it is noteworthy that 54.8% of the incidents recorded in the database involve mayoral figures (Figure 8). In addition to mayoral candidates and pre-candidates, serving mayors, ex-mayors, and ex-mayoral candidates have also been victims of political-electoral violence.

This allows us to confirm that the role of mayor and the functions associated with the post, and not the person behind the post, appear to be the epicenter for practices of political-electoral violence. This reflects the analysis of candidate protection mechanisms undertaken by Ana Velasco for Noria-MXAC. According to the study, in Mexico, mechanisms to minimize violence perpetrated against political figures during the electoral cycle have focused on the candidates, which has led to a number of limitations, which are detailed by the author. By contrast, reviewing the Italian case study presented by Ana Velasco highlights how, in that country, more than protecting candidates, measures aimed at decreasing electoral violence focus on dissolving local administrations affected by the collusion between the political elite and the mafia. Therefore, rather than temporarily assigning security details to mayors, these measures seek to neutralize access by violent groups to local public administrations.

Furthermore, our database reveals that 39% of the victims of violence had already suffered some form of violence in the past. This suggests that, on the one hand, the trend of violence seen during this electoral process is part of a larger trend that requires more in-depth analysis. Furthermore, it shows that those who participate in the political game, especially candidates, do so in the knowledge, experienced first-hand, that they are at risk of being a victim of violence, and, despite this, they continue along this path.

Qualitative research, which will be published on our website shortly, will complement these hypotheses and investigate the motivations behind and the conditions under which a candidate decides to remain in the political game despite the danger this poses to his or her life.

Party affiliations

With regard to the victims’ party affiliations, data shows that 54.1% of victims were members of one of the country’s three major political parties: Morena, PRI and PAN (Figure 9).

In a context of previously unimaginable political alliances, it is important to explore to what extent the construction of these agreements could be associated with the incidences of violence. According to the data compiled from press coverage, 15% of the victims were members of a political party alliance. Although this is not a majority, it does open the door to discussing to what extent coalitions can lead to violence, under certain conditions.

For example, if the violence is the result of inter-party tensions stemming from the decision to create coalitions, this would show that the agreements reached by party leaders to create a common front is not necessarily easy to replicate at a local level. In order to explore this possibility, a more in-depth analysis would characterize the way in which local parties implement the alliances decided on at a national level. Furthermore, in certain cases it is possible that the forging of an alliance would increase the risk of losing power, and, as a result, any violence could be attributed to the confrontation this generates. Admittedly, the data available is not sufficient to prove these two points without further analysis.

Even though Morena recorded a higher number of incidents (22.9%), the data shows that 74% of the victims belonged to an opposition party, while 26% were members of the governing party. This is true in every state, with the exception of Chiapas. This leads us to focus on the resistance of figures in power to ceding spaces to their opponents or reacting to the possibility of losing their grip over local power.

We know that 12% had belonged to another party in the past. This should lead us to the following question: what led to this change in party, and how much did it influence patterns of violence? The answer remains open.

In this sense, it would seem that we have repeated one of the findings in the aforementioned study by Combes: political violence could result in resistance from those holding positions of local power with regard to the arrival of greater political pluralism. However, these scenarios must be put to the test by compiling wider-ranging data, which, on numerous occasions, goes beyond that available in statistical records.

The affiliation of the victims, despite the information that it provides, says little or nothing about intraparty tensions, i.e., the conflicts among groups within the same political party. This aspect is relevant because there are no reasons to believe that political parties have any internal cohesion, especially during such tumultuous times and especially at a local level.

This means that the careers of politicians and candidates within their own parties, in addition to the internal dynamics of the latter, are another aspect that should be systematically researched using other methodological resources. For now, we know that 12% had belonged to another party in the past. This should lead us to the following question: what led to this change in party, and how much did it influence patterns of violence? The answer remains open.

The alleged perpetrators of violence

One of the most important aspects regarding the incidences of political-electoral violence is the identity of the perpetrators.

As has been mentioned previously, the lack of sources of judicial data means that any information compiled talks about ‘alleged perpetrators’, since there is no information about sentences that clearly accredit their responsibility. Furthermore, after reviewing what the database showed about alleged perpetrators, we must not lose sight of the fact that this comes from media coverage. So, those who have identified the alleged perpetrators of these acts of violence are reporters who, in turn, may have paraphrased statements made by the authorities, eyewitnesses, or versions of the incident that they use as a source of information. Therefore, this data is not exempt from bias associated with the type of sources that reporters use in their articles, and it is then recorded in the database.

After reviewing what the database showed about alleged perpetrators, we must not lose sight of the fact that this comes from media coverage.

So, those who have identified the alleged perpetrators of these acts of violence are reporters who, in turn, may have paraphrased statements made by the authorities, eyewitnesses, or versions of the incident that they use as a source of information.

However, bearing that in mind, it is worthwhile analyzing who, according to local and national news coverage, the perpetrators of this violence actually are.

Leading news headlines, such as “the drug trafficking vote” and “the organized crime party”, are frequently seen during this electoral cycle. Based on these headlines, it is easy to deduce that those responsible for the recorded political-electoral violence are involved in ‘organized crime’, and they also show that these violent incidents are part of a much wider context of the ‘war on drug cartels’. However, a more cautious review process would allow us to not only minimize the emphasis that tends to be focused on such a generic actor as ‘organized crime’, but it would also lead to a series of questions about what we know about the alleged perpetrators and what remains in the blind spots of the data available.

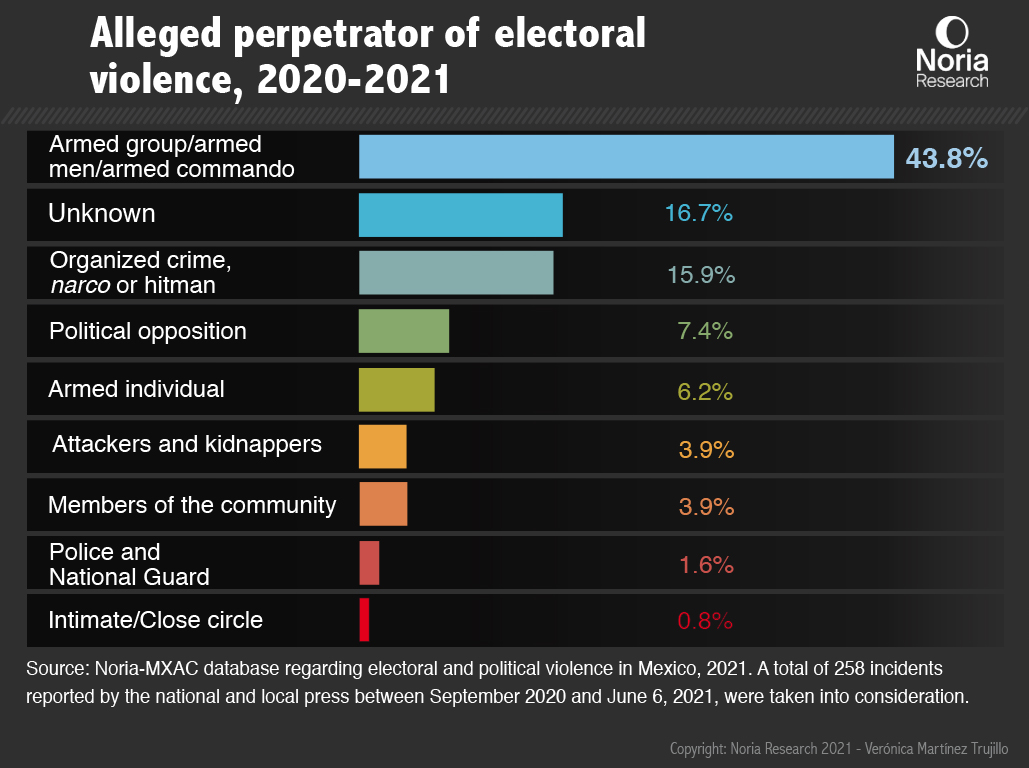

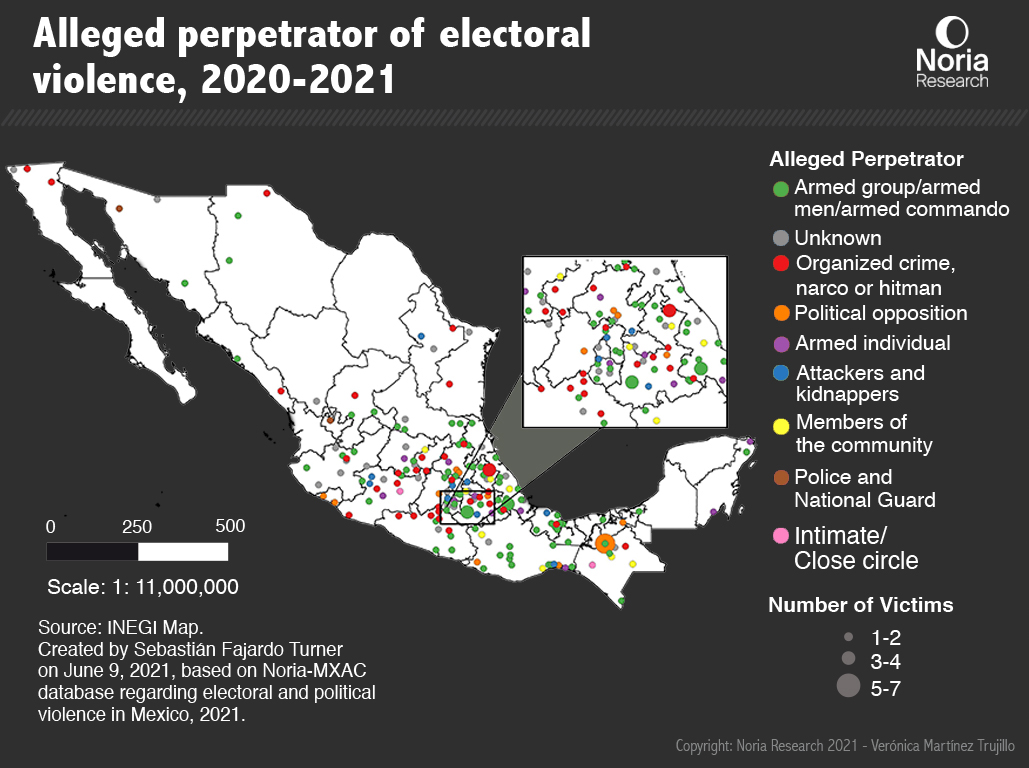

As shown in Figure 11, 43.8% of the incidents are associated with an armed group, armed man or armed commandos as the party responsible for these violent acts. This is followed by similar levels of cases in which the party responsible is unknown (16.7%) and those attributable to organized crime, drug cartels or hitmen (15.9%).

What do we talk about when we talk about armed men?

If we focus on the first label, we note that the notion of “armed men” says little or nothing about who is materially and intellectually responsible for the violence in question.

On the one hand, it is certain that it once again elicits questions about the availability of firearms; however, its generic nature leads to more questions than answers. How many? Although they are within the same category, is a group of 3 armed men comparable to a group of 10 or 20? Who are they? Are they working alone or for some else? If the latter is true, then for whom? What are their reasons? Who ordered the use of violence? Why do they act as a group and not on an individual basis? How organized are they? Are they long-standing groups, or have they recently been created? Do they have any other activities as a group, in addition to perpetrating violent acts? Where did they learn about violence, and to whom do they offer their services?

In any case, these findings allow us to highlight the fact that, when we talk about armed groups as the perpetrators of the political-electoral violence , we credit the idea that in Mexico there are dozens of configurations where violent actors who, under certain conditions, can employ this “know-how”. In fact, it has been documented that both local chiefs and leaders, not to mention business owners or industrial leaders, have groups of “armed men” at their service to protect them.8

The notion of “armed men” says little or nothing about who is materially and intellectually responsible for the violence in question.

As this is the case, the question that we should ask ourselves is: under what conditions could these actors use these violent resources in the political game? Is the outcome of an election such a threat that these local actors feel they have to deal with it through their violent protectors? A more comprehensive search should focus on this idea in order to identify explanations that, most certainly, will go far beyond narratives such as “drug cartels are voting to control the territory”, whatever that actually means.

Now, as we have mentioned, thanks to the data we know that in 16.7% of the cases compiled in the database the perpetrator of the violence is unknown. This means that the articles published in media outlets do not mention the alleged perpetrators or explicitly state that it is unclear whether there was one or more assailants, or what they looked like. This is a relevant piece of data, not only because it ranked as second highest on the list of alleged perpetrators, but also because in a context where there are high levels of impunity, this proportion shows us that any attack – including homicide – that occurs during a time when all eyes are focused on campaigns, messages and candidates, could occur without any clues as to who is responsible.

What about ‘organized crime’, cartels, and hitmen?

It is important to focus on the figure of “organized crime”, drug cartels and hitmen.

Firstly, the data shows that the explanation that political-electoral violence occurs because cartels are seeking to infiltrate the political arena, more than a certainty, becomes a possibility that merits further discussion. As shown in Figure 12, the incidents attributed to organized crime are concentrated in areas such as Guerrero, Michoacán, Guanajuato and the State of Mexico, which are considered to be zones of conflict between different cartels.

As occurs in the homicides registered in Mexico, distinguishing between those attributable to organized crime and those stemming from other acts of violence represents a major challenge. However, this process has been simplified by classifying any incident that fulfills certain criteria as being the work of “drug cartels”

However, in these zones – and in others – there is an abundance of incidents that have been attributed to armed groups and men, broadening the scope of the category and leading us to ask ourselves the following question: how do we know if an attack or a homicide is the work of organized crime or a group of armed men? This means that we should focus the discussion on the way in which violence is classified as being “the work of narcos” (Escalante, 2012).

As occurs in the homicides registered in Mexico, distinguishing between those attributable to organized crime and those stemming from other acts of violence represents a major challenge. However, this process has been simplified by classifying any incident that fulfills certain criteria as being the work of “drug cartels”: the type and caliber of the firearm used; whether or not there are any signs of torture or physical damage; whether there were any messages from a specific group taking responsibility for the incident; and even whether the incident took place in an area in which there is deemed to be a conflict between drug cartels.

This means that, based on a series of attributes, an act of violence is declared to be the “work of drug cartels”, as if they had a signature form of dying or killing. So, based on the modus operandi, deductions are made regarding the parties responsible or, at least, the focus is then turned on an entity that is defined as being responsible. Although these deductions may be based on historical records or characterizations inspired by well-documented criminological studies (for example, those studies focusing on the mafia), what is true is that unless there are serious judicial investigations, this classification represents an arbitrary, and somewhat artificial, process.

One of the implications of classifying political-electoral violence as “something to do with organized crime” is that, in terms of public opinion, the case is then deemed to be closed. As has been widely documented, violence attributed to organized crime tends to be accompanied by narratives such as “they are killing each other” or “there must be a reason why they were killed”.9 This means that the violence in question “involves other people”, those who inhabit a world far detached from that of ordinary citizens. If it were drug cartels, it seems that no further information is required: “they were up to something”, which, reading between the lines, means “they deserved it”.

Based on a series of attributes, an act of violence is declared to be the “work of drug cartels”, as if they had a signature form of dying or killing.

So, based on the modus operandi, deductions are made regarding the parties responsible or, at least, the focus is then turned on an entity that is defined as being responsible.

The problem is that the “others”, this time around, aspired to represent us in local legislative and executive powers. The problem is that “there must be a reason why they were killed” is not an explanation, much less proof. The problem is that “drug cartels” are an vocable that obscures one (or various) intellectual and material authors, and, as such, their motives and incentives. The problem is that “it was the drug cartels”, although it seems sufficiently robust as a social sentence, is not a judicial sentence, and it ends up absolving the State from the responsibility of implementing measures to prevent this violence or process it judicially if and when it occurs. If that were not enough, by saying “it was the drug cartels”, they are massively exculpating other political actors – government officials or local leaders – who may be directly involved in these acts of political-electoral violence.

Finally, the data that we have compiled regarding alleged perpetrators highlights the role of other actors who are not precisely consigned to the imaginary criminal underworld: political opponents, members of the community, members of the victim’s circle, and even State agents. Although it appears that there are few cases registered with this criteria, they do show how, in the political game, legal actors can opt for violent mechanisms to manage tensions or confrontations, a trait that is widely confirmed in the numerous testimonies collected during field work in the country’s most violent regions.

So, the line that divides what is legal from what is illegal once again becomes blurred, pointing towards the idea that, which is also the case in terms of the phenomenon of political-electoral violence, more than illegal actors, we tend to observe an intricate configuration of (potentially) violent actors who use these tools to play the political game.

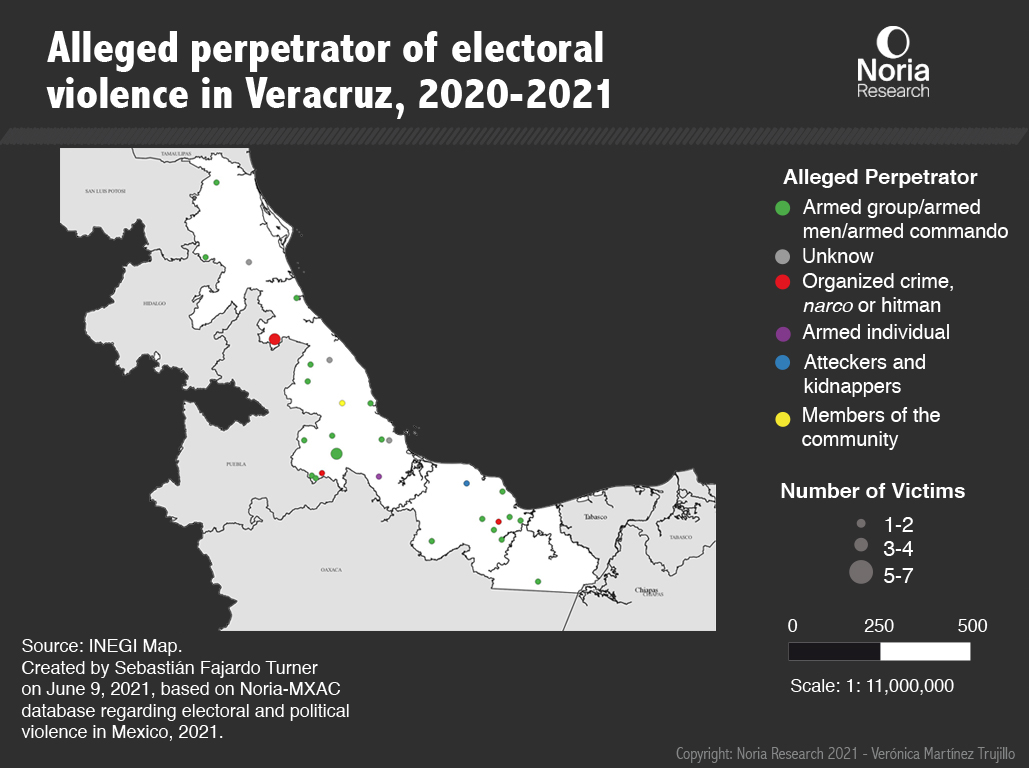

What happened in Veracruz, the most violent state in 2020-2021?

The highest number of incidents recorded in the Noria-MXAC Database 2021 come from Veracruz, making it the most violent state in the country during the previous electoral cycle. A total of 41 incidences of political-electoral violence were recorded, of which, 53.7% were attacks, while 41.5% were homicides.

As occurs at a national level, mayoral figures are the most vulnerable; however, this figure is 20 percentage points higher in the state of Veracruz than the national average of 54.8%, given that incidences involving mayoral figures in Veracruz reaches 75.6%. As shown in Figure 14, 34.2% of incidents were perpetrated against mayoral candidates, 19.5% against pre-candidates or those aspiring to stand as candidates for mayor, 14.63% against ex-mayors, and 7.32% against serving mayors.

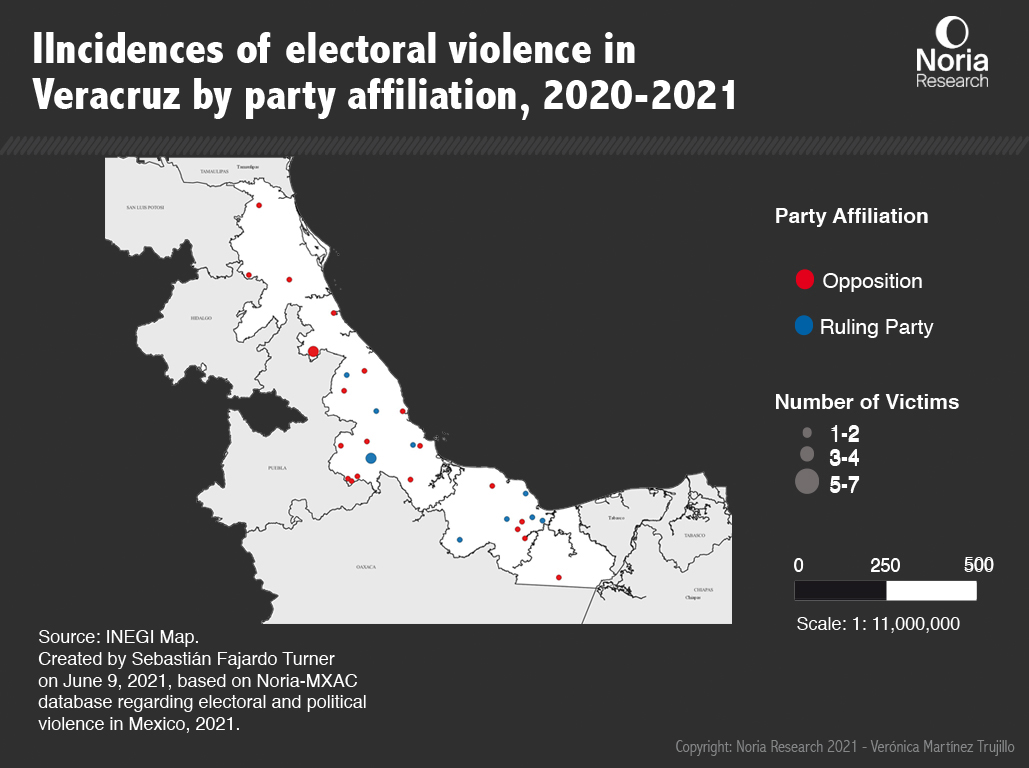

In terms of party affiliation, it is important to highlight the fact that 26.8% of victims were members of the PAN political party. This is noteworthy as, given that this party governs 66 of the state’s 122 municipalities, its candidates and party members were the victims of violence especially in those municipalities in which they were the opposition party. Morena, which one 16 municipalities in the 2017 election, is ranked second in terms of victimization, given that 19.5% of incidences of political-electoral violence were perpetrated against its members.

The level of violence against those running for election, compared to those running for re-election, is higher, which is consistent throughout the country, as illustrated in this map that highlights the location of classified incidences based on the victims’ party affiliations.

Based on the data relating to party affiliations and the primacy of victims who were members of the opposition, a more in-depth exploration of the extent to which inter- and intra-party competition is a relevant factor in explaining the political-electoral violence in the state.

As such, once the results of the election held on June 6 become official, it would be worthwhile to analyze whether there was a close race in the municipalities in which there were violent incidents, especially homicides, as well as to ascertaining whether the governing party was re-elected or if the opposition party came to power. Furthermore, a more detailed review of the context surrounding the campaign and all relevant actors is required, i.e., factors that are not necessarily covered in the press when a violent incident is reported. This would help hone the explanations and data behind the cases that we have covered or the patterns that we have measured, both in Veracruz and in any other state of interest.

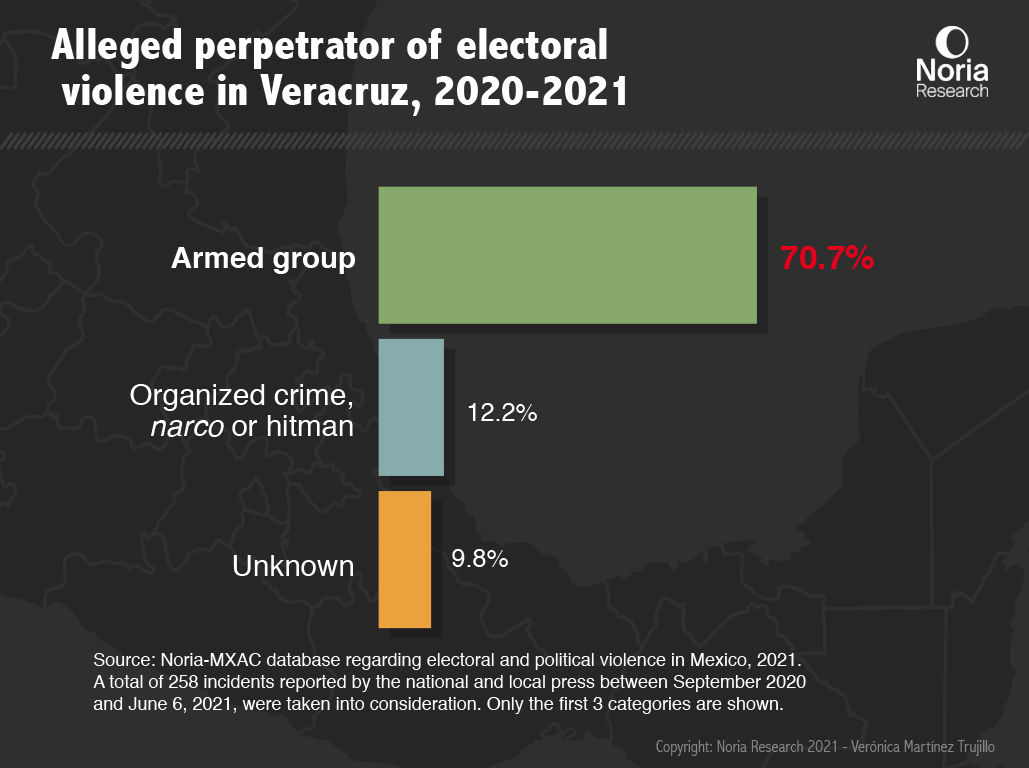

This route of analysis is fed by those individuals that the press articles compiled identify as being the alleged perpetrators. In Veracruz, 70.7% of the acts of violence are attributed to an “armed group”. There are no labels for “armed commando” in this national analysis. This leads us to the question about the relevance of certain concepts within a regionalized or localized language, compared to terms that flow freely within the Mexican vocabulary. In any event, the figure of an “armed group” continues to be a vague response to the question of who commits violence against local politicians.

In Veracruz, investigations have begun surrounding a case that highlights some of the workings that could be behind these “armed groups”. The assassination of René Tovar, Movimiento Ciudadano’s candidate for the mayorship of Cazones, just days before the election was recorded as having been perpetrated by a group of armed men who attacked him at his house. The candidate, who actually won the election, died on his way to hospital, leaving his candidacy to his alternate – his campaign coordinator. Over the next few days, the Veracruz State Attorney’s Office (FGE) held the substitute mayor on suspicion of being involved in the homicide of his colleague. Although the investigation is still on-going, and any speculation could impact on the suspect’s right to presumption of innocence, the case illustrates that, at least within the remit of the investigation, behind these “armed groups” there may be representatives of local politics looking to settle conflicts or make their political aspirations a reality through violent acts, including murder.

Despite the fact that the electoral violence in Veracruz has tried to be explained by the presence of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), only 12.2% of cases are attributed to organized crime, drug cartels or hitmen, while in 9.8% of cases the perpetrator is unknown.

The case leads to a series of core questions: under what conditions does a local politician have access to an armed group willing to commit murder? To what extent does violence, as a resource that is available to certain local politicians, condition the political game? What is the relationship between political-electoral violence and violence that goes beyond electoral processes?

Despite the fact that the electoral violence in Veracruz has tried to be explained by the presence of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), only 12.2% of cases are attributed to organized crime, drug cartels or hitmen, while in 9.8% of cases the perpetrator is unknown. The data appears to draw a line that leans further towards political tensions between local actors. This does not rule out the possibility that the presence of this cartel or other criminal groups is behind, or at least part of the reason for, this violence, but it does lead us to the conclusion that it should be studied not only as a criminal phenomenon inspired by the search for money, but also as an analysis of political-criminal configurations. This is a more complex approach, but one that is probably more relevant.

Once the political-electoral violence witnessed by the inhabitants of Veracruz during this electoral cycle has been characterized, at least generally speaking, we are left with the question as to what type of effects this has on the democratic life in the municipalities and areas affected. Do the patterns of violence inhibit people’s participation in the election process? To what extent is voting, as an emblematic exercise in democracy, change?

Although the data compiled in the 2021 Database that we analyzed does not provide any clues about the implications of violence on the future of the election, thanks to the data provided by the electoral authorities, we can at least explore the possible effects on voter turnout.

What is the effect of violence on voter turnout?

As shown in Figure 19, the voter turnout recorded in Veracruz in 2021 was considerably higher than that for other mid-term elections (60.06%), almost reaching the levels recorded for elections that occur at the same time as presidential elections. Furthermore, turnout was above the national average (52.6%). This suggests that, despite being the state with the highest number of recorded incidences of violence, this has not had a negative effect on turnout at elections.

A more in-depth analysis of not only the different types of violence, but also the effect on turnout and other traits of democracy at a local level, would be worthwhile. For example, did the violence recorded during the campaign inhibit the organization of assemblies, rallies or public events? Did it persuade potential voters to explicitly support a given candidate? Did it hinder the participation of any sector in particular?

The case of Veracruz provides a series of leads for analysis and proposes questions that help us look beyond counting cases and incidences of violence.

Furthermore, it highlights the importance of analyzing the dynamics behind electoral and political violence at a state-wide level, creating a strategy that would allow us to better understand and better tackle this phenomenon. Finally, this case highlights how analysis at a local scale requires a long-term approach, supplemented through mid- and long-term field work. Otherwise, the data compiled will not be sufficient for satisfactory explanations.

The lights and shadows of a ‘peaceful’ election day

After a 9-month campaign, and given the violent context we have mentioned, the expectations for a violent election day seemed justified. So, when the electoral authorities confirmed that 99.98% of polling sites had been opened –the states of Michoacán, Oaxaca and Tlaxcala were unable to open all polling sites – and that the vast majority of trained polling officials had carried out their duties under optimum conditions, we caught our breath, rating the June 6 election as a peaceful election day. However, a series of violent incidents recorded on the day led us to qualify our statement and discuss how “opening polling sites” does not necessarily mean that violence, and the effects it has, can be left behind.

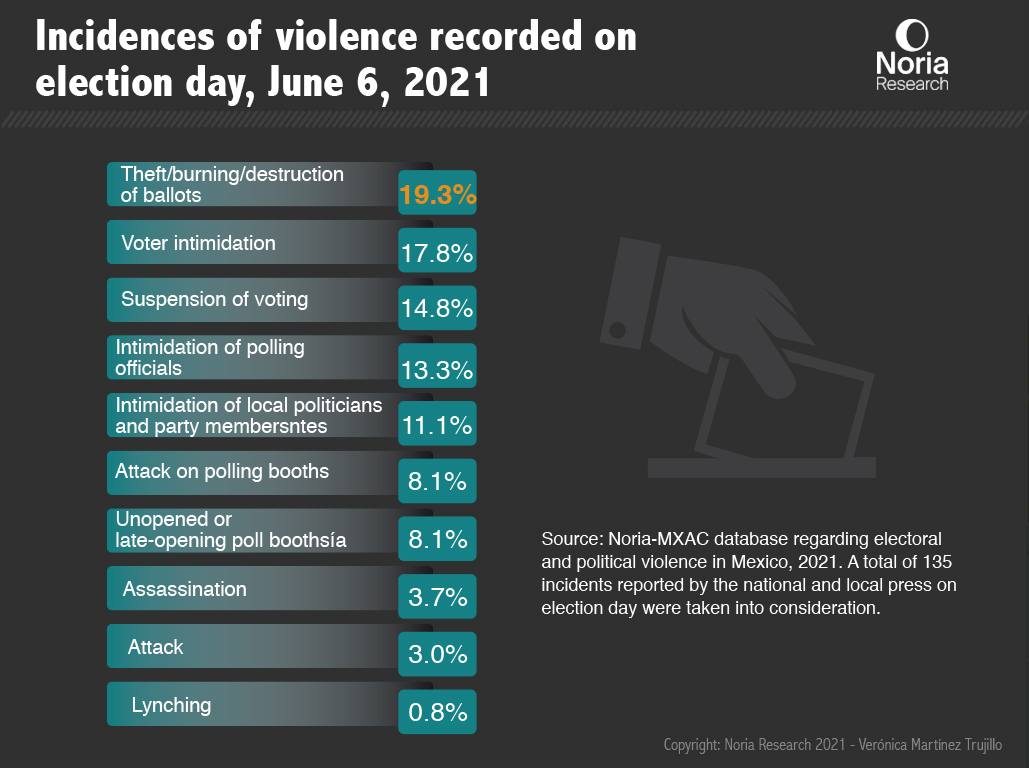

As part of the work undertaken to create the Noria-MXAC Database on political and electoral violence, we recorded violent incidents as reported by the local and national press during election day. This component of the Database contains 135 incidents, stemming from both the work done by the reporters and correspondents stationed in each area, and from the reports published by electoral and government authorities and published by the media.

If we consider the fact that, on election day, 19,915 local posts were up for election (including 15 governorships and 1,923 mayorships), not to mention 500 federal posts, 135 incidences of political-electoral violence does not seem to be a significant number. However, as shown in Figure 20, a series of incidents that, clearly, sought to hinder the electoral process occurred, leading to acts of violence against polling sites, their officials or voters.

In more than 20 cases, ballots were stolen, burned or destroyed. Despite this, in the areas in question, the polling sites continued operating and the election was not interrupted. There was even at a shoot-out at one polling site. So, when the number of polling sites opened is used as a means of measuring the normalcy of an election, the occasions on which this occurred within a context of violence tend to be overlooked.

Furthermore, the reports compiled highlight acts of voter intimidation (18.2% of the total number of incidents), including attacks, shootings and the carrying of firearms. The data does not show what effects this voter intimidation had, such as, for example, if it hindered turnout or led to voters favoring a certain candidate. Once more, a more detailed analysis at a local level, which goes beyond merely counting cases, would offer us a better understanding of the impact this violence has on democratic life in these areas.

15.2% of the incidents reported on election day led to the definitive suspension of voting given attacks and the theft or destruction of ballots. 13.6% of cases involved the intimidation of polling officials by blocking polling sites, attacks and even death threats. Ten attacks on polling sites were also recorded, leading to the destruction or vandalizing and blocking of facilities, as well as the use of harmless artifacts that simulated explosive devices. Finally, there were a dozen cases in which polling sites were not opened or were opened late as a result of anticipated security conditions or violent confrontations between members of different political parties. For example, in Apatzingán, Michoacán, some polling sites were not opened because members of the community were demanding that the elections be held under a customs and traditions model, while in Jerez, Zacatecas, some polling sites were not opened because, according to the press, there were security issues relating to organized crime.

In addition to violence, the goal of which was to hinder the voting process, there were cases of intimidation against local politicians and party members (11.1% of recorded incidents) that includes property damage, shootings and other attacks. We should not overlook the case of the party members assassinated in Pueblo Nuevo, Chiapas.

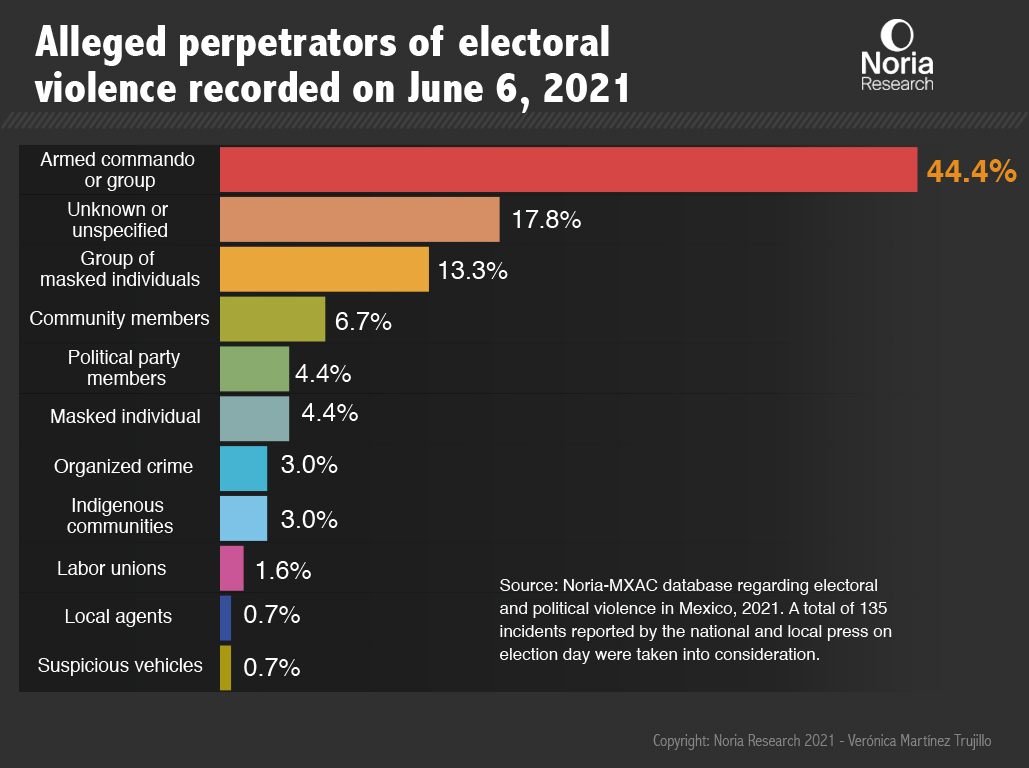

Who are those allegedly responsible for the incidences of political-electoral violence that took place on election day?

Armed commandos or groups once again appear as the alleged perpetrators (42.5% of recorded incidents). Once more, the availability and use of firearms is shown to be a core trait in acts that focus on hindering the outcome of the election. In 18.2% of cases, the alleged perpetrator is still unknown, while in 13.6% of cases they were carried out by a group of masked men.

Only 3% of recorded incidents are attributed to organized crime, a lower figure than that of cases attributed to a masked individual. Also noteworthy is the use of “suspicious trucks”, which, according to the press, were used to intimidate voters. In this case, it would appear that a reputation for violence and the fact that members of the local community know the possible perpetrators of violence are enough to intimidate polling officials and voters.

In this report, we also discuss the figures of members of the community, party members, labor union groups and municipal agents, highlighting how we tend not to categorize these actors as violent, despite the fact that they were involved in these practices. So, once again, it becomes evident that there is a need for a more detailed analysis of these cases.

Compiling and analyzing the data available opens up myriad possibilities of understanding a topic that merely counting cases does not. In this first review, we have tried to explore new ways in which to broaden the scope of the discussion surrounding this topic, but, above all, to define a series of relevant questions, to which there are no simple answers, and, which, we, as a society, should never stop asking ourselves.

This report is part of the Elections & Violence in Mexico Project

Data production and analysis are coordinated by María Teresa Martínez Trujillo

Click here to read our Policy Report on candidates protection protocols in Mexico

Click here to go back to the Project’s main page

Notes

- It is important to take into account the way in which government authorities register and report data about violence, such as homicides, no matter if it is within a political-electoral context or not, as this could be analyzed as public policy, in as such as they providing information about what a government is doing or not doing in light of a public problem. ↩︎

- We are currently undertaking this process at Noria-MXAC in order to find more answers to the questions that have inspired this project. ↩︎

- See for example the work of Guillermo Trejo and Sandra Ley (2020); the data produced by Integralia or Etellekt, two major consulting firms. ↩︎

- Christine Hine, Virtual Ethnography, Sage Publications, 2000. ↩︎

- Pablo Piccato, A history of infamy: crime, truth, and justice in Mexico, University of California Press, 2017. ↩︎

- Lawrence Freedman,The Future of War, NY: Public Affairs, 2017. ↩︎

- Interview conducted by María Teresa Martínez, June 3, 2021. ↩︎

- Martínez-Trujillo, M. T., Bussinessmen and Protection Patterns in Dangerous Contexts: Putting the Case of Guadalajara, Mexico into Perspective, PhD. Dissertation, CERI-Sciences Po, Paris, 2019. ↩︎

- Blazquez, A. (2017), «Enquêter en terrain suspect : usages de contraintes à Badiraguato», en Micropolíticas de la violencia : reflexiones sobre el trabajo de campo en contextos de guerra, conflicto y violencia, Cuadernos de Trabajo de MESO, No. 5,p. 34-45; Escalante, F. (2012), El crimen como realidad y representación, El Colegio de México; Mendoza, N. (2008). Conversaciones en el desierto: Cultura y tráfico de drogas, CIDE. ↩︎