This report is part of the Elections & Violence Project

The report has been produced by Ana Velasco Ugalde, and coordinated by María Teresa Martínez Trujillo and Romain Le Cour Grandmaison

Introduction

Mexico’s transition to democracy has been a process characterized by plurality and alternation, but also by violence. Through multiple expressions and a range of intensity over time and throughout the country, political-electoral violence has raised doubts about the authorities’ ability to guarantee free and safe elections for its citizens, both in terms of exercising their right to vote and their right to be voted for.

Article 216 of the General Law of Electoral Institutions and Procedures is clear with regard to the importance of the voting process: “Safeguarding and protecting electoral ballots is considered to be an issue of national security”.1 As such, the law stipulates specific security measures for the entire electoral process, from the printing of ballots to requesting support from police officers for all levels of government – or even the involvement of the armed forces – in order to guarantee order on election day.

What has been taken from this legal text is the need to create institutional vote protection measures as a strategic issue, while understanding its role as a possible threat to State stability and security.

In light of this context, the pertinent questions to be asked are: what happens when this violence is not directed at voters or election organizers, but rather at those men and women who are standing for election? What formal measures have been implemented to safeguard candidates within the country? What do the protocols that have been implemented reveal about how threats are perceived and how they should be handled?

In short: how can we ensure that elections do not become a matter of life or death for the candidates?

In this text, we analyze the formal mechanisms implemented by the Mexican State to prevent, identify, handle and sanction violence in electoral contexts. The objective is to, firstly, summarize the institutional efforts that have been made in recent decades. This will enable us to question the idea that no attempts have been made by the government to temper the problem, or even if any recent efforts have been made. Based on this review process, it will be possible to posit a series of ideas that analyze the positive impact public policy has had on this phenomenon, in addition to reviewing the main limiting factors.

What formal measures have been implemented to safeguard candidates within the country? What do the protocols that have been implemented reveal about how threats are perceived and how they should be handled?

In short: how can we ensure that elections are not a matter of life or death for the candidates?

The exploration of the formal measures that have been implemented is also useful in shedding light on the constant tension that exists within the federal authorities, and between the latter and the local authorities, in terms of the complexity of defining responsibilities, the room for discretion that the law offers in terms of designing and implementing protection measures, and the limitations in the Mexican State’s approach, in comparison to, for example, similar experiences in other countries.

The basis of this text is not to review the law, but rather, based on it, better understand how the problem is being conceived and from which direction it has been approached.

Part 1 – Protection Protocols in Mexico

Presidential Elections: the Old Matter of Concern

Historically speaking, measures to protect candidates in Mexico are linked to the democratic transition.2 In 1990, the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) was created as an autonomous body tasked with organizing and guaranteeing impartiality in the electoral process. The Federal Electoral Institutions and Processes Code (COFIPE), the legal framework for the IFE, includes a provision regarding protecting presidential candidates. Article 183 stipulates that the president of the Council (of the IFE) may request from “the corresponding authorities” the personal security measures deemed necessary for candidates.3 Its predecessor, the 1987 Federal Electoral Code, did not include this provision.4

However, it is important to highlight the ambiguity in the way in which both the adjudication of responsibilities and the definition of a process and its effectiveness are drafted. To begin with, the obligation of the electoral authorities to assist or intermediate can only be activated at the express request of a candidate, but it does not outline under what situation of vulnerability it was possible to do so, nor how this was to be achieved. It does not describe whether the authorities tasked with providing protection had previously evaluated the relevancy of the request – as they were also liable for absorbing the cost of this process -, nor what the ”personal security measures” they offered were.

The basis of this text is not to review the law, but rather, based on it, to better understand how the issue of electoral violence is being conceived and from which direction it has been approached.

There was also no indication of who the competent authorities were, i.e., whether the request was made directly to security institutions, such as the police or Armed Forces, or if there was an intermediary. It is important to take into account these gaps that have been present since the initial regulations were implemented, as they will provide the basis to allow us to review the evolution of this mechanism and how it has been interpreted based on changes in government or in light of specific situations.

The drafting of the base mechanism within the COFIPE became clearer during the 1994 presidential elections, the first to be organized by the IFE. As had occurred since at least 1988, the body tasked with protecting presidential candidates, if requested, was the Presidential General Staff (Estado Mayor Presidencial – EMP).5 This involved the assignment of a security escort that worked in coordination with the candidate’s team and the local authorities during the campaign.

The fact that the EMP was already providing this type of protection to presidential candidates prior to the creation of the IFE suggests that Article 183 of the COFIPE absorbed and institutionalized a practice that already existed, in addition to ensuring a more democratic approach and making it available to any candidate no matter their party affiliations. The responsibility of the EMP continued up until 2019, when this body was disbanded at the behest of the current Executive Branch.6 To date, it is unclear who will be the new “competent authorities” tasked with taking over from the work undertaken by the EMP during the next presidential elections given that, despite reforms to the Army and Armed Forces Act that state that those who belonged to the EMP would be reintegrated into the Armed Forces, it is not clear what will happen to the functions they exercised.

The next adjustment to the specificity of the protection mechanism took place in 2006 with the incorporation of the Mexican State Department (Secretaría de Gobernación – SEGOB) as an intermediary between the candidates, the IFE, and the EMP. In January of that year, a support agreement was published in the Mexican Official Gazette (DOF) “covering the area of security for presidential candidates from the different political parties during the 2006 electoral process.”7 Said agreement stipulated that SEGOB would be the institution tasked with receiving the request from the president of the Board of the IFE and relaying this information to the EMP, in addition to ensuring that it would handle any unforeseen circumstances.

The objective, according to the document, was to help contribute “to the security and trust in” the electoral process, “ensuring the country remains in a state of governability.”

This agreement is relevant for two reasons:

- It establishes a clear process and assigns responsibilities.

- It recognizes the task as one of governability, not merely security, bringing it within the SEGOB’s sphere of influence as the coordinator of this mechanism.

The Integration of Federal Deputies to the Mechanism

The 2008-2009 federal electoral process, during which the Chamber of Deputies was renewed, increased the scope of this mechanism for these candidates. In January 2009, the IFE presented an agreement with political parties that included, for the first time, a provision to protect candidates seeking to be elected to the federal Chamber of Deputies.8

In January 2009, the IFE presented an agreement with political parties that included, for the first time, a provision to protect candidates seeking to be elected to the federal Chamber of Deputies.

One year prior, a new version of the COFIPE had been issued, modifying the wording of the provision regarding candidate protection: “The president of the Council may request from the competent authorities personal security measures for those candidates who require said measures, as well as for Mexican presidential candidates, from the moment in which, based on the internal mechanisms within their party, they are requested to that effect.”9 The agreement states that the request for protection may be made to “the competent federal, state or local authorities”.10 This means that the EMP is not tasked with providing security in these cases, and, the local level is “recognized” by the mechanism for the first time. It is important to highlight the fact that the context in which these adjustments were implemented was at the beginning of the “War on Drugs” and there had already been a recorded increase in incidents of political and electoral violence. In the states with high levels of violence, such as Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla and Michoacán, there were 2 cases recorded in 2007 but a total of 14 in 2008.11

Despite the adjustments that were being made to the mechanism, there was still a significant margin for discretion. For example, it was still unclear how the responsibility to protect candidates was to be defined, especially in terms of the possibility of the participation of local or state authorities in this process.

Electoral Authorities, Security, and a Measure of Success

In spite of the fact that, at first glance, the ambiguity in the mechanism could be deemed a fault, it is worthwhile reviewing its implications.

Firstly, it is necessary to highlight that in Mexico, the electoral authorities are not responsible for providing security. The work they do focuses on ensuring that the process, especially election day itself, takes place without any setbacks. In efforts to achieve this goal, it is possible that they may encounter security, logistics or technical problems, and, as such, they may request support from the institutions with these faculties. This is how it is included within their regulations.

It is important to highlight that in Mexico, the electoral authorities are not responsible for providing security. The work they do focuses on ensuring that the process, especially election day itself, takes place without any setbacks.

However, the creation of a more specific security process not only exceeded their field of expertise, but it also presented obstacles to the work they do. These comments were made to us by public officials interviewed for this report. In other words, it is not that they are unaware of these security problems; in fact, the opposite is true – they must fully understand them in order to be able to carry out their work; however, their obligation lies not in finding a solution to them but rather avoiding them affecting the process. For example, electoral authorities in the state of Guerrero, a state in which organized crime is a major issue, we were told that electoral authorities do not use “risk maps” to decide where to open polling booths, given the fact that if they did so, it would be likely that many would never be opened. What they do is to talk to and negotiate with the communities and local or federal institutions responsible for security in the area, including the deployment of the Armed Forces, in order to guarantee that the polling booth is set up correctly, the ballot boxes are protected, and all ballots are transported safely.

It is important to analyze these questions. For motives based on history and even international reputation, the Federal government is extremely jealous when it comes to its electoral process. In recent years, for example, we have noted that the indicators to measure the success and quality of the democratic action of voting revolved mainly around the opening of 100% of polling booths in the country, the prevention of fraud, and the effective counting of votes. In other words, and this must surely have something to do with the scrutiny of international organizations and bodies – the OAS and OECD, for example – what is important is logistics. Not necessarily how many candidates have been threatened or who have lost their lives during the electoral process.

Along the same line, violence against candidates who are politically visible and important, may have a direct and resounding impact on the legitimacy and reliability of the process, as was the case with the assassination of the PRI presidential candidate in 1994, Luis Donaldo Colosio. Viewed from this angle, it makes sense that the mechanism, in this preliminary stage, focuses only on protecting federal candidates: the protection of these candidates safeguards the process itself.

Since the 2000s, the indicators to measure the success and quality of the democratic action of voting revolved mainly around the opening of 100% of polling booths in the country, the prevention of fraud, and the effective counting of votes.

However, as the security situation worsened in various regions in the country, the authorities involved in this protection mechanism began to face a new dilemma. For the IFE, the task of reinforcing the electoral process became more complicated as it became a major player with key information regarding the conditions on the ground vis-à-vis electoral security. The Federal Government, on the other hand, was waging a battle to ensure that the “War on Drugs”, and the violence associated with this endeavor, would not have an impact on local electoral processes, fueling the narrative that there was no control over the territory. Meanwhile, it had to strike a political and institutional balance: remaining on the sidelines of the electoral process while ensuring that it was held in a peaceful setting that did not the democratic stability of the country at risk. Finally, the local authorities were left holding a timebomb. They had no protection protocols in place for their candidates, all while facing exploding situations of violence. The remaining question was a simple, and yet crucial one: who was tasked with protecting them, and what was the best way in which to do so?

Part 2 – The Violence that Never Happened? The 2012 Elections

“We must recognize that, despite the fact that it is not a generalized trend, there have been public security issues and incidences of interference, attempts at meddling by organized crime in some elections.”12

At the beginning of 2012 and with the presidential elections just around the corner, the then Secretary of State, Alejandro Poiré, euphemistically acknowledged the difficulties facing the electoral process. Just a few days before the 2010 local elections in Tamaulipas, the PRI candidate for governor had been assassinated.13 The following year, in elections held in the state of Michoacán, an organized crime group called Los Caballeros Templarios, publicly pressured people to vote for the PRI, a party that had not been successful in the state’s previous elections.14 This intimidation apparently worked. The PRI won in Michoacán and after the elections one cartel leader, Servando Gómez Martínez, La Tuta, called mayors to demand a periodic payment of a percentage of the public budget.15

The scrutiny of international organizations and bodies – the OAS and OECD, for example – what is important is logistics.

Not necessarily how many candidates have been threatened or who have lost their lives during the electoral process.

This declaration by the person in charge of domestic security at a time when public debate focused solely on the “War on Drugs” highlights the level of alert in place at institutions linked to the election process. The expectation of the electoral authorities was that the 2012 elections, the largest in history at the time, could become marred by violence.16 However, the predicted violence never happened, and the number of victims was considered to be low, at just three: two mayoral candidates and one local congress candidate assassinated.17

The Protocols’ Evolution, On the Road to 2012

Our goal here is to review if mechanisms implemented by the federal authorities may have contributed to mitigating the number of incidents.

The measures taken by the Federal Government began several months before Poiré’s statement, while Francisco Blake Mora was still the head of SEGOB. From the beginning of 2011, the then Secretary of State signed several specific agreements with the states that were to hold elections that year: Guerrero, Baja California Sur, Coahuila, Nayarit, the State of Mexico, and Hidalgo.18

At the beginning of 2012 and with the presidential elections just around the corner, the Secretary of State euphemistically acknowledged the difficulties facing the electoral process.

These resolutions consisted of coordination agreements with a range of security institutions in each state, including the participation of federal forces to protect each stage of the electoral process. This suggests that more than a national plan, at that stage there was a case-by-case approach that relied on working directly with local authorities instead of a uniform national protocol.

This trend becomes more obvious in the case of Michoacán, which, as mentioned previously, also had elections that year. Two and a half months prior to election day, in August 2011, Blake Mora – from the PAN – and Governor Leonel Godoy Rangel – from the PRD – signed an agreement that included a security coordination protocol, a provision covering the assignment of a security escort for candidates who requested one, and a new proposal: the creation of a negotiating body to predict and resolve conflicts among candidates and political parties through a dialog-based approach. This mechanism seems to indicate, once again, the willingness to tackle this phenomenon as one that is rooted in governability and not merely security, and it highlights how the federal and state governments were warning that political tensions could lead to violence during the electoral process, in addition to threats being made by organized crime.

Despite these efforts, once these agreements had been signed, the violence that, as mentioned previously, plagued the November elections in Michoacán highlighted at least two limiting factors of this strategy being spearheaded at the time by SEGOB.

The first weak point in the Michoacán strategy became clear after the assassination of the mayor of La Piedad on November 2, 2011, nine days after the election. This incident clearly highlighted how not only candidates were at risk, but also elected officials. When questioned by the media, several days after the event, regarding the security measures in place for mayors, Secretary Blake stated that the federal government was unable to provide additional security to mayors.19 In truth, this protection loophole is not unique to Michoacán; in fact, it is part of the design of the base mechanism, which only contemplates candidates who are recognized by their political parties and the electoral authorities.

The 2011/2012 resolutions consisted of coordination agreements with a range of security institutions in each state, including the participation of federal forces to protect each stage of the electoral process.

This suggests that more than a national plan, at that stage there was a case-by-case approach that relied on working directly with local authorities instead of a uniform national protocol.

The second limiting factor of this mechanism became evident in light of another tragedy. Two days prior to the elections in Michoacán, on November 11, Secretary Blake was killed in a helicopter crash. The sudden absence of the coordinator of the political negotiation body led to its collapse at a critical moment.20 This means that the lack of institutionalization of these mechanisms transfers the personal responsibility for their effectiveness directly to public officials, and, as such, discretion comes into play.

For 2012: a New Agreement with IFE

After these events, the SEGOB started collaborating with the IFE to draft a cooperation agreement. This document was signed in December 2011 by the new Secretary of State, Alejandro Poiré.21

The new agreement included crucial new additions. For the presidential elections in July 2012, SEGOB would coordinate protection measures being offered to candidates running for office who requested it, and not only for presidential candidates and those running for the Chamber of Deputies, as had been the case up until then. The IFE would be tasked with implementing communication and coordination mechanisms with security institutions through local taskforces. This agreement was the springboard for innovative and more wide-ranging coordination efforts firstly among federal institutions, followed by state and local authorities. As such, this agreement highlighted how this phenomenon was being tackled not as a transversal public policy issue, but rather by using SEGOB as an indispensable intermediary to help navigate and reconcile electoral issues with public security activities.

For the presidential elections in July 2012, SEGOB would coordinate protection measures being offered to candidates running for office who requested it, and not only for presidential candidates and those running for the Chamber of Deputies, as had been the case up until then.

SEGOB quickly developed three specific mechanisms to tackle violence within the electoral process.

The first encompassed the task of identifying electoral zones with a risk of violence and potential issues for the opening and operation of polling stations. This translated to the rolling out of support for the electoral authorities. This mechanism relied on cooperation and information sharing between the latter and the federal government in order to create a communication channel based on trust that should not be taken for granted. As explained previously, since its creation, the IFE has faced a difficult situation in which to fullfil its duties, which has increased the degree of protectionism regarding its procedures and resources.

The second mechanism consisted of a candidate protection protocol. This encompassed the assignment of state law enforcement agents to act as a security escort, a process that was generally assigned to the federal police force. This assignment was coordinated by a Security Taskforce comprised of the SEGOB and federal security agencies. Despite the fact that any candidate could request protection, the job of this taskforce was to assess who was going to receive it, given that not all cases represented the same level of risk.

The members of this taskforce used intelligence information and other data to allow them to assess the risk presented by the candidate in question. As a result of limited resources and the chronic mistrust between federal and local authorities, it is difficult to say that this assignment would be dealt with a universalist vocation. In the case in study, this highlighted the fact that, for example, there was a possibility that a security escort would be assigned to a candidate who had ties to organized crime.

The third was the creation of a political dialog commission comprising political parties and the IFE. As mentioned previously, this mechanism had been tested in the past. In any event, the public officials that we have interviewed estimate that this allowed them to address areas of tension among political parties during the 2012 elections. Furthermore, this mechanism reaffirms the fact that this perceived threat could not only be attributed to criminal groups, but also to other political actors.

The Complicated Collaboration between Federal and Local Authorities

To replicate national security task forces, the fourth mechanism focused on the creation of bodies to coordinate with different states. There are at least two important points to be analyzed regarding these bodies. The first focuses on selectivity, as they were not created in each state, only in those with the highest levels of political violence. This is in keeping with the key point of this phenomenon, which is the variation in the level of violence that exists at a regional level, for example, in terms of the range of potential perpetrators of violence in each state.

In interviews conducted with ex-public officials, they referred to the examples of Campeche, where there was no need for these mechanisms given that there appeared to be no risk to candidates; Oaxaca, where violent incidents required greater political dialog as they were not necessarily related to organized crime, but rather to another form of local conflict; and Michoacán, where the problem was clearly organized crime. It would seem that this fourth mechanism would require not only working alongside local authorities, but also a wide-ranging understanding of the situation in different parts of the country.

In Mexico, the efficiency of the mechanisms is not associated with established institutional protocols, but rather an interpersonal capacity to negotiate, collaborate, and undertake tasks in a precise and defined manner.

The second relevant factor is the importance of the partnership between federal and local authorities. Given that this type of coordination is generally complicated, this element gains greater importance in a situation of mutual mistrust, such as was the case at the time. On the one hand, the federal government, especially President Felipe Calderon, repeatedly stated that some local authorities were possibly linked to organized crime. On the other hand, some local opposition governments questioned the legitimacy of the president as a result of doubts raised by the opposition candidate regarding the 2006 election. These sources of tension make coordination activities even more complicated, such as was the case of Guerrero, where the authorities we interviewed stated that they had had difficulties cooperating with multiple public institutions.

Those people interviewed also admitted that the low number of incidents, which they say can be attributed to the mechanisms in place at the time, could have been, above all, the result of interpersonal dialog that existed between the groups at that time. Based on their a posteriori analysis, they believe that those who were coordinating efforts from SEGOB and IFE had prior experience in security and electoral issues. This not only meant that they had the necessary know-how in both fields, but they also had shared experience prior to becoming part of this taskforce. This, they say, facilitated an unparalleled synergy that facilitated cooperation.

Despite the value that these relations could have had on achieving a much less violent electoral process than was expected, it must be highlighted that, once again, this shows that the efficiency of the mechanisms is not associated with established institutional protocols, but rather an interpersonal capacity to negotiate, collaborate, and undertake tasks in a precise and defined manner.

Despite the apparent success of the mechanisms implemented in 2012, no measures were implemented to protect those who continued to be at risk after the election, nor were any agreements or protocols drafted to ensure the continuity of the mechanisms for future elections.

In fact, despite the apparent success of the mechanisms implemented in 2012, no measures were implemented to protect those who continued to be at risk after the election, nor were any agreements or protocols drafted to ensure the continuity of the mechanisms for future elections. From the latter, there are two key takeaways, at least. Firstly, if, more than within the mechanisms themselves, the key lies in the synergy between government and electoral authorities, these efforts may not be able to continue when public officials are replaced, as happens once an administration ends. Secondly, this creates crucial issues of institutional memory, especially in terms of policies in which a large number of actors are involved, and in which not all details of day-to-day operations are documented in agreements and protocols.

Part 3 – Violence Unleashed: the 2018 Elections

As happened in 2012, the 2018 electoral process was preceded by an increase in indicators of violence throughout the country. In Chihuahua, in 2013, a PRI mayoral candidate for the town of Guadalupe y Calvo was kidnapped and murdered.22 In 2015, in the State of Mexico, the PRD candidate for the seat of Valle de Chalco wasassassinated at his campaign headquarters.23 In Guerrero, in 2015, the mayoral candidate for the PRI-PVEM coalition for the town of Chilapa was killed in a shootout during his campaign tour.24

These episodes of violence, among many others, especially from 2015 onwards, sounded the alarm regarding a complex outlook for the 2018 elections to be held in June. Despite this, no-one had foreseen that this would be “the most violent process in the country’s history”, with a total of 152 candidates assassinated between September 2017 and June 2018.25

New Protocols

The SEGOB, this time with Alfonso Navarrete Prida at the helm, maintained its role as coordinator in terms of the implementation of the base mechanism, using an extremely cautious strategy in terms of communication.

In April 2018, the SEGOB presented, alongside the head of the National Electoral Institute (INE) – the successor to the IFE –26 the “Personal Protection Protocol for Presidential Candidates.”27

In 2018, the law finally stated that any candidate could seek official protection in Mexico.

Navarrete stated that the National Security Commission (CNS) and the EMP would be tasked with ensuring the security of presidential candidates, and that requests should be made via the President of the INE Council and SEGOB. It is important to remember that, during the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, the CNS had taken over the functions of the defunct Ministry of Public Security and was incorporated into the SEGOB. In other words, according to the 2018 protocol, the SEGOB would continue to coordinate efforts, but it would not be responsible for public security.

During the event in question, Navarrete also stated that not only presidential candidates could request protection, but also any other candidates, with the difference being that the federal police force and “civilian authorities” would be tasked with providing the protection required.28 This is the result of the INE’s General Law of Electoral Institutions and Procedures keeping the same wording as the last version of the COFIPE with regard to the base mechanism, although now contained in Article 244, in which it formally increases the scope of the provision to cover “candidates who require it, in addition to presidential candidates”.29

One notable aspect of the presentation of the protocol, and which is also a constant in terms of Navarrete’s communication after the elections, is his insistence that the federal government should not intervene in the electoral process. Despite the fact that this message was also publicly communicated in 2012, the emphasis made by the head of SEGOB in 2018 merits closer attention.30 We must remember that the federal government was acting within an adverse context of public opinion and intense international scrutiny. The numerous landmark cases of human rights violations, such as in Ayotzinapa, and scandals including Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s escape from a high-security prison, not to mention the PRI’s ominous electoral past in previous decades, were major incentives for SEGOB to seek to safeguard the electoral process and reinforce its image of neutrality. Therefore, being overly present in local elections could be easily seen as deceitful interference in the electoral process. However, the political decision to maintain its distance is questionable when faced with the number of deaths recorded during those elections.

A clear example of the international pressure on the federal government and its difficulty in promoting its insistence on neutrality was its communication with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IAHCR). In May 2018, the IAHCR called on the Mexican State to urgently put a halt to the increasing violence against candidates.31 According to the press release, between September 2017 and April 2018, there had been multiple acts of violence perpetrated against people who held and had held office, as well as against pre-candidates and candidates, especially at a local level.

Four days later, the head of SEGOB gave a press conference during which he defended the federal government’s position. Navarrete reaffirmed that the current administration was acting in strict compliance with federalism and the law, and he repeatedly called for political parties and presidential candidates to initiate dialog to tackle the issues of governability and security.32 He also made a plea to avoid political debates inciting violence and condemned acts of aggression against candidates, although he did not refer specifically to the victims.

“They Are Killing Each Other”

Several weeks later, during a press release regarding an operation entitled Operativo Escudo-Titán, Navarrete stated that, to date, protection was being offered to 30 candidates at a federal level and 6 at a local level, all of whom had requested this measure.33 He also maintained that the majority of cases that had already been reviewed by the state attorney’s offices, found that the violence was the result of disputes among “organized crime” groups, and were personal and family issues or linked to the local political contest.34

While stating that it is “organized crime” means that the legal responsibility of addressing this crime would fall within the remit of the federal government, the phrasing refers to the narrative of “they are killing each other”. This not only reinforces the dominant hypothesis that electoral violence follows an exclusively crime-based pattern, but it also allows the authorities to eschew any responsibility of preventing, investigating, or solving these deaths.

A posteriori, when analyzing the levels of violence reached during the 2017-2018 electoral process, it appears evident that the federal government’s strategy failed. This is particularly of concern at a local level, where there is a world of difference between the SEGOB’s communication about its protection measures and the number of deaths, threats and intimidations recorded.

While stating that it is “organized crime” means that the legal responsibility of addressing this crime would fall within the remit of the federal government, the phrasing refers to the narrative of “they are killing each other”.

This can be explained in part by Article 244 of the electoral law.35 This article is not explicit in explaining the obligations of providing security to local candidates and, as such, it provides the authorities with a loophole to eschew their responsibility. This indicates that, despite the experiences of previous elections in the implementation of a clear protection mechanism, there still exists a degree of discretion. As such, the scope of the mechanism continues to depend on the incentives and on the willingness and specific – and perhaps interpersonal – synergies of the authorities at the time.

The paradox is that the evidence from 2018 indicates that the Mexican State can have an extremely violent electoral process for those citizens who aspire to hold public office at any level of government and still act in strict compliance with the law.

Part 4 – Elections of 2021: Ongoing Violence

The 2018 elections not only marked the arrival of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) to presidential power and a major political change, but they also represented a before-and-after of how electoral violence is handled in Mexico when they were declared – and duly recorded – as “the most violent in recent history”.36

Perhaps as a result of this classification and the concern surrounding the size of the elections in June 2021 – the “largest elections in history” – the federal government opted this year to implement a protection mechanism that evokes the protocols implemented by the PAN-led government in 2012. However, there are also a number of significant differences that must be analyzed.

The Strategy Against “the Organized Crime Party”

For the elections on June 6, 2021, the guidelines focused around the “Electoral Context Protection Strategy”, presented on March 4 of this year by the Minister for Citizen Protection and Security (SSPC), Rosa Icela Rodríguez Velázquez. This policy is spearheaded and coordinated by this institution.37 A few weeks after the elections, it appears that violence was not prevented – as 101 candidates were killed, for example. Yet, these figures will be analyzed in a different report. Here, we will focus on the evaluation of the model.

First, it is important to look at the institutional evolution promoted by the government. In fact, the current mechanism offers a different variable for analysis compared to its predecessors: it is coordinated by the SSPC and not by SEGOB. This is primarily the result of an institutional shift that began in 2018. At the beginning of this administration, the old SEGOB lost a number of its faculties and resources. These were taken over by the SSPC and the Ministry for National Defense (SEDENA). Similar to the arguments provided by the ex-authorities, the design and implementation of this protection mechanism combines a public security approach and a major element of governability and coordination with numerous federal and state public institutions. For example, governors, electoral authorities, state and local police, and the Armed Forces.

2021: the actions indicate that within the SSPC there is clarity regarding the need for grassroots understanding of the threats being made to candidates and, as such, of the actions to be taken and the need for cooperation with local authorities.

Second, the coordination component appears upon careful review of the new strategy, which encompasses four areas of action: four dealing with intermediation or negotiation, and another four that focus more on protection. The first group contains an appeal to political parties and electoral authorities to comply with the law, taskforces that comprise political parties and local authorities, consultations with governors, and weekly strategy evaluations. The second group contains efforts to consolidate the Security Strategy in high-risk states and towns, support for candidates at all levels of government, support for local polices forces to help safeguard the election process, and the establishment of territorial protocols. Together, these actions indicate that within the SSPC there is clarity regarding the need for grassroots understanding of the threats being made to candidates and, as such, of the actions to be taken and the need for cooperation with local authorities.

However, these guidelines do not publicly and in detail outline the responsibilities of the other federal institutions involved in this Strategy: the Mexican State Department, the Office of Legal Affairs, the Financial Intelligence Unit, and the National Intelligence Center (CNI).38 As a result of the violence mentioned by Rodríguez when referring to the “campaign of fear”, it can be inferred that the SSCP focuses its efforts on the first two, given that they coincide with the actions described in the previous paragraph, while the other institutions would review the co-opting and imposition of public officials, illegal campaign financing, and complicity.

This indicates that, as confirmed by the federal public officials interviewed, that the institutional framework for the protocols encompasses two levels: the first and most visible is with those institutions tasked with coordination and protection, while the second is with those who undertake intelligence and legal support work.

The 2021 Protocols

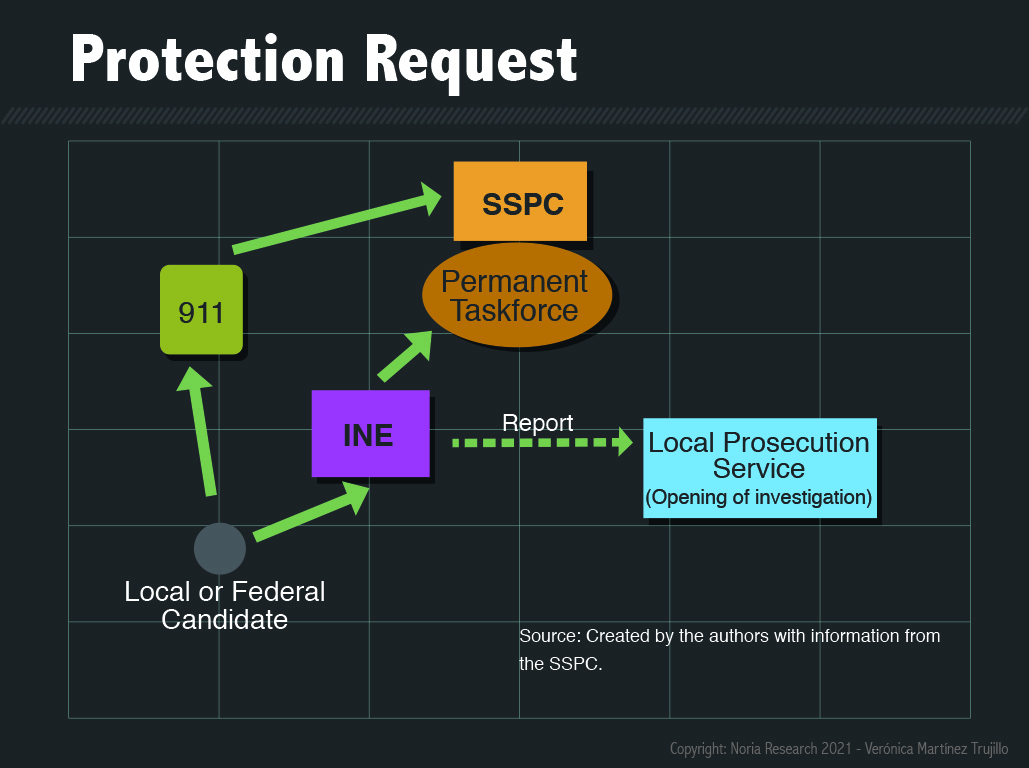

According to the SSPC, the mechanism has been designed at a national level, meaning that it must be implemented in a similar manner throughout the country. More specifically, it works in the following way: any candidate, at either a federal or local level, can contact the electoral authorities to report a threat. If running for federal office, he or she must contact the INE; if it is for a local political office, he or she must contact the corresponding state electoral institution. Another means of filing a report is by calling 911.

As illustrated in Figure 1, any report filed, via either of the two routes, is channeled directly to the SSPC, which acts, firstly, as a central hub, and then as an intermediary between the electoral authorities and the institutions that will provide protection to the candidate in question. The area responsible for these tasks within SSPC is the Policy and Strategy Unit for the Construction of Peace in States and Regions (UPECPE).

Figure 1: Protection Request

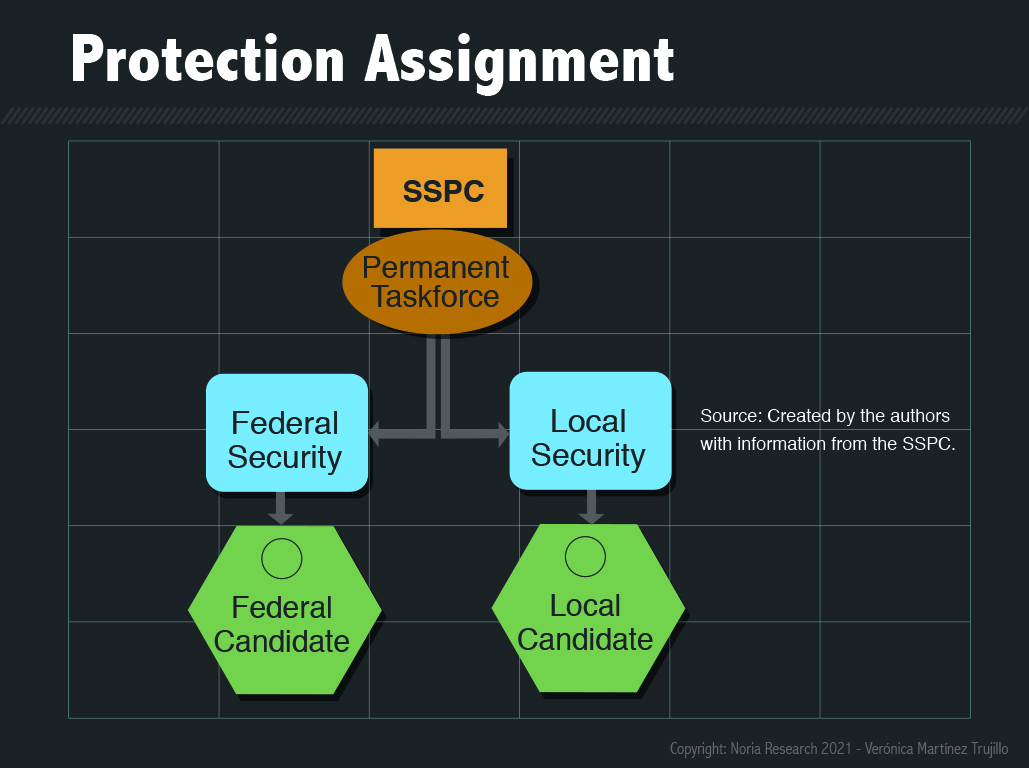

Then, the report is sent directly to the monitoring center of the Permanent Electoral Strategy Taskforce (Figure 2), which is coordinated by the SSPC. It works 24 hours a day and all relevant federal institutions are represented. It is coordinated by the Unit. The goal, according to the SSPC, is to analyze the threats on a case-by-case basis and assign the protection it deems necessary.

Figure 2: Protection Assignment

According to the SSPC, the goal lies in streamlining the response that, using traditional channels – via local police departments or prosecution services – would take too long or could get lost. Despite the fact that the need for urgency could be justified in numerous cases of threats, the decision by the SSPC to centralize responses removes this responsibility from other institutions. Without detailing specific institutions, in an interview with members of the SSPC, references were made to strategies of resistance within the bureaucracy to not attend requests or demands on an urgent basis. This is similar to what happened in 2012 with the creation of the “Security Taskforce”, which also acted as a hub to respond to protection requests made by candidates.

There are also two important points. The first is that no clear information has been given about the criteria used to calculate the level of risk. Minister Rodríguez presented the classification of cases divided into three groups – serious, preventive, and relevant – but she did not provide further details about the criteria for each division.39 It is likely that they exist but have not been presented, or perhaps there are none, and the assignment of a security escort is decided on a case-by-case basis. If this is the case, there may be a margin of discretion when assigning protection, which calls the neutrality of the mechanism into question. There are precedents regarding the politicization of security in previous administrations40, and this issue is a source of concern given that, in 2018, the majority of the victims were from opposition parties.41

On the other hand, the fact that a federal authority acts as the central hub for responses calls into question the role of the local authorities, particularly at a municipal level. There may be cases in which marginalizing them is justified if there is collusion with the perpetrator, or if they are, in fact, the perpetrator themselves. However, this does not explain if this possibility is taken into consideration and, if so, by whom – perhaps the CNI. Moreover, if collusion is detected, it does not establish the legal action to be taken as a result.

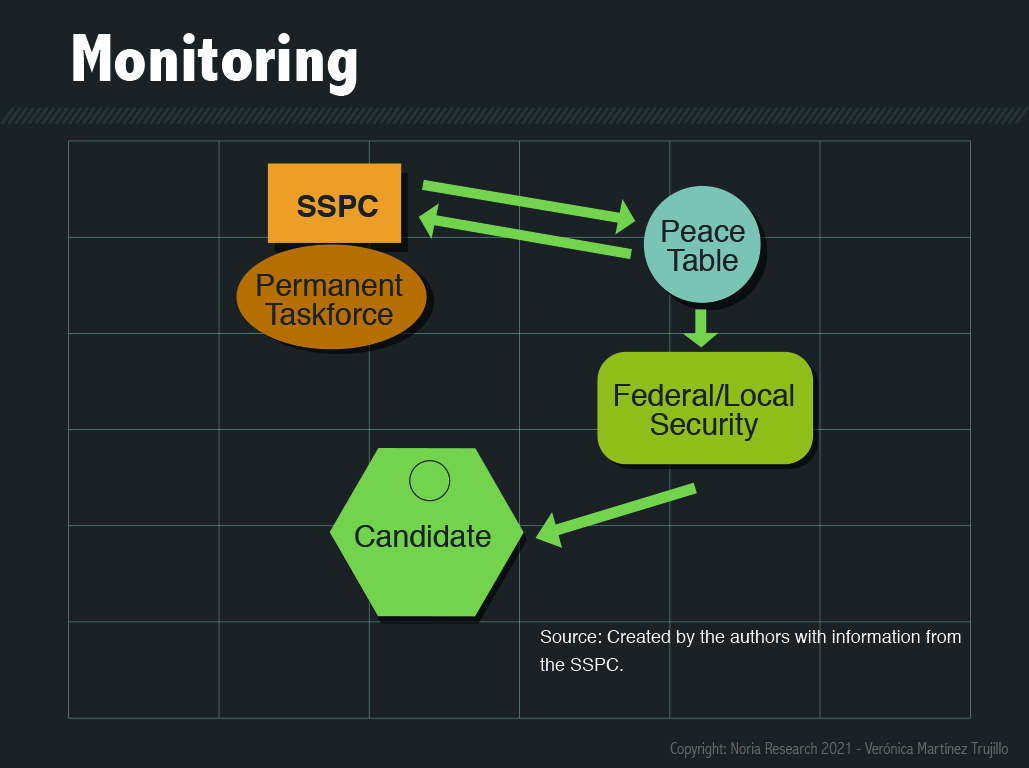

In the next stage of the process, in order to monitor the assignment of protection in each case, the SSPC relies mostly on the Construction of Peace and Security Taskforces (see Figure 3). These bodies were created at the beginning of the administration as part of the National Public Security Strategy, and their goal is to share information and coordinate actions.42 In this case, they are used as a point of liaison with the local authorities, and they allow the SSPC to monitor each case on a weekly basis, as well as redirecting responsibility to their counterparts. This is for those cases in which the security is coordinated by the state police, which, according to Minister Rodríguez, represent 60%.43

The focus of the SSPC lies in combining a strong capacity for centralization with the need to liaise with states in order to enable them to exercise their responsibilities. This can contribute to the allocation of operational tasks, which is in keeping with the institutional federalism approach. However, this can also lead to the transferal of these public policy tasks and their costs to the states, with the federal government eschewing a number of its responsibilities, especially if the narrative continues to focus on electoral violence as a manifestation of organized crime, which is a federal felony.

Figure 3: Monitoring

This is not a minor issue. The tension between the states and the federal government in terms of security has been on-going for years. In September 2020, for example, 10 opposition governors abandoned the National Governors’ Conference.44 At least two of these were from states with the highest levels of electoral violence, such as Jalisco and Tamaulipas.45 This raises doubts about the federal government’s ability to negotiate and coordinate with state authorities, especially those with complex security situations and opposition governments, as is the case of Guanajuato46 and Sonora,47 and, as such, its effectiveness in implementing this mechanism and the SSPC’s leadership as a political intermediary.

Our Analysis – Going Beyond the Temporary Protection Formula

The mechanisms reviewed in this text are all based on the same basic formula: in light of a threat, any citizen running for public office can request the intervention of the electoral authorities to ensure that security institutions, through a federal government coordination institution, assign them protection.

This was the basic formula designed by the IFE in 1990, and it is still present today. During some administrations, the executive has tried to design an implementation mechanism that makes this response more wide-ranging and effective, but there is no obligation on federal, state, or local governments to do so.

Currently, 21 states have candidate protection measures.

Yet, some of the states that do not have these measures are among the most violent, including Veracruz, Michoacán, the State of Mexico and Puebla.

This point is notorious in state electoral laws and codes, which do not do much to consolidate the base mechanism. Currently, 21 states have similar candidate protection measures. Some of the states that do not have these measures are among the most violent, including Veracruz, Michoacán, the State of Mexico and Puebla. The drafting of the provision is a transposition of the federal law, which is why the wording is practically identical. For example, Article 244 of the Tamaulipas State Electoral Law states that: “The president of the Council may request from the competent authorities personal security measures for those candidates who require them, from the moment in which, based on the internal mechanisms within their party, they are requested to that effect.”48 However, this does not mean that all states see this as an issue that must be addressed, as they continue seeing this as the responsibility of the Council of the INE, which ties their hands in the matter. And, as can be seen in the wording of the current INE electoral law, the allocation of responsibilities and the process itself are both ambiguous.

After reviewing the implementation of the mechanism from its inception, there are several limiting factors.

-1- The feasibility of access to the mechanism.

According to the SSPC’s explanation, the mechanism is, apparently, easily accessible. The incentive for candidates to file a report is that they will receive effective protection through formal channels. But this is based on the assumption that there is a level of trust in the local authorities’ ability to file the report and fullfil their responsibility. This structural limitation had already been noted in mechanisms implemented in previous years, when they were coordinated by SEGOB.[56]

-2- The next question must then be: what options are available for candidates to obtain protection?

In certain cases that we have documented that involve local candidates, there are efforts to skip the local authorities and the institutional chain of command in order to directly access federal resources. This can be achieved through personal connections, political party networks or the candidate’s own experience. These channels alter the equality of accessing protection as there will be those people who do not have these resources. Another possibility is that they will resort to informal protection, using violent local individuals as protection, seeking to engage the services of private security companies, or entering into informal arrangements with authorities or public forces present in their territory. This entails the de facto disabling of the mechanism

-3- The time for which protection is offered to local candidates.

For example, in 2018 there were 11 assassinations recorded during the transition period in the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla and Michoacán. Once the campaigns had come to a close, so too did the operational side of the strategy. If the candidate wins, he or she may be able to replace their security escort. However, if they lose, he or she becomes a citizen who has attracted attention, which could lead to new threats. No matter the case, the tragic outcome that is trying to be avoided, an attack or assassination within an electoral context, ends up occurring despite prior efforts and investment during a different scenario.

This limiting factor can be observed in all the strategies herein reviewed, and, in fact, it is an inherent part of the design of the mechanism. One solution could be to extend the protection period, but this does not truly help to neutralize the threat. In essence, the job of the mechanism, both the current one and those employed in previous administrations, is to temporarily increase the cost for perpetrators of achieving their goals when the authorities are providing protection, but this does not remove the incentives for threats or attacks. This happens because the strategies fundamentally focus on withstanding the threat in order to protect the electoral process, not neutralizing it to decrease the chances of it happening again.

Finally, it is important to highlight the lack of institutionalism of the mechanism. As described earlier, the common denominator of the 2012 and 2021 strategies was the room for discretion they offer and the fact that both are underpinned by the specific leadership skills of public officials and, of course, the support of the administration at the time. This means that these were executive decisions. However, this is where their major weakness lies. There is no follow-up when the administration changes, and the only protocol that demands continuity is the protection of presidential candidates, as this has not been dependent on the political volition of the administration at the time in question.

The goal is to achieve a public policy that does not depend on this variable. An important question to ask, therefore, is whether it is convenient or not to institutionalize a protection mechanism based on the good practices and experiences. However, it is also possible to look back and question what other way can we understand, and better tackle, the phenomenon of political and electoral violence?

International Experiences: The Case of Italy

A relevant issue in understanding institutional responses and identifying areas of opportunity is to review those found in other countries. Italy is an interesting case study given the relevance of violence being perpetrated against candidates or public officials over the past number of decades, in addition to the articulation between these facts and a number of criminal organizations – the different mafias, to use a generic term that includes, for example, the Sicilian Cosa Nostra, the Calabrian Ndrangheta or the Camorra from Naples.

Italy is a particularly interesting case study because of the level of documentary evidence and research that there is in this area, undertaken both by the State – particularly through anti-mafia justice – and by academia and civil society. If that were not enough, the advances that have been made in reducing violence are a good reason to take a more careful look at this case study.

Italy is an interesting case study given the relevance of violence being perpetrated against candidates or public officials over the past number of decades, in addition to the articulation between these facts and a number of criminal organizations.

Beyond using it as a comparison – the Mexican and Italian situations are, without a doubt, extremely different – we are interested in finding references to public policy that support lessons about what works and what does not, in addition to the conditions under which this is the case. This entails responding to questions about how other States approach electoral threats and what formal mechanisms they have implemented.

In Italy, as in Mexico, organized crime groups represent a strong threat at a local level.49 This enables them to co-opt, run or seize public budget resources and channel them into their own economic interests. Unlike Mexico, the use of homicidal violence seems to have progressively reduced, leaving in its place a greater integration of the formal and informal economies – something that has been increasingly observed in the country.50 As such, methods of intimidation against candidates have evolved to threats or violence against assets, such as is the case of the burning of vehicles.51

Despite the aforementioned, and unlike Mexico, Italy does not have dedicated tools for protecting candidates from violence perpetrated within electoral contexts. In fact, there is no specific protection mechanism enshrined in Italian law. However, the Italian approach is interesting as it seems to focus more on the systemic collusion that may exist between local governments and criminal groups, which could indicate a willingness to tackle this issue in a more comprehensive and long-term manner, and not only during elections.

The Italian approach seems to focus more on the systemic collusion that may exist between local governments and criminal groups, which could indicate a willingness to tackle this issue in a more comprehensive and long-term manner, and not only during elections.

In effect, the measures that the Italian State have taken to counteract mafia involvement in local government are: 1) dissolving local governments that have been infiltrated by the mafia; 2) prohibiting anyone who has been found guilty of being involved in organized crime after the process of dissolution from standing as a candidate. Both tools highlight the tension between the different levels of government and the vulnerability that exists on a local scale, as can be seen in Mexico, in addition to the structural potential that legal mechanisms that aim to neutralize this threat can have, moving beyond situational protocols that only seek to mitigate the immediate risks for candidates.

Our task lies in asking a series of questions about how these different legal mechanisms in Italy work based on the variables of the game, such as, for example, the definition of specific characteristics of organized crime groups, local and national political balances, and the presence of other players who have an interest in local politics. It is important to mention that this section will not provide an exhaustive overview of the area, but rather it will provide possible areas of reflection and pave the way for researching it in a more in-depth fashion.

Dissolution of Local Governments

In Italy, the most notorious measure, which was integrated into the national legal framework in 1991, is the dissolution of local governments. This is a unique tool to combat and prevent serious criminal infiltration in local governments.52 The goal of this law is to “eradicate the relationship between local politics and the mafias to ensure the impartiality, efficiency, effectiveness and transparency of public administration”.53

In the dissolution mechanism, the mayor or provincial president, city hall, and city or provincial government, in addition to any person involved, is removed. “Infiltration” does not only take into consideration agreements reached when these public officials were in office, but also the contamination of the electoral process. An example of this are pre-electoral agreements between candidates and criminal groups. This means that the goal is to decrease, from the very first time they try and engage with a future elected official, the incentives for the mafia to infiltrate the government.

The dissolution process is based on an investigation undertaken by a committee to try and find “real, unequivocal and relevant”54 indicators of a relationship between members of the local government and mafias, or if there are any influences that put the independence of the public administration at risk.55 The responsibility of implementing the mechanism falls on the Prefect, a post that represents the national government at a local and provincial level, who can fully exercise the functions of the State.

In Italy, the most notorious measure, which was integrated into the national legal framework in 1991, is the dissolution of local governments. This is a unique tool to combat and prevent serious criminal infiltration in local governments.

In the event of suspected infiltration, the Prefect convenes an investigative committee comprising three public officials from the national government. They are tasked with compiling evidence in a period of between 3 and 6 months. When they finish their investigation, they prepare a report for the Prefect, who, based on the evidence, decides if there is sufficient proof to take the case to the Interior Ministry. If this happens, the Ministry prepares a proposal for dissolution that is discussed during the Ministerial Council. In the event the dissolution of the local government is authorized, the decree is emitted by the President within a period no greater than three months after the Council’s decision has been made.

In the decree, an extraordinary commission comprising three members (public officials or members of the Judiciary) will take over the local administration for a period of between 12 and 24 months, at the end of which new elections are organized. The Ministry of the Interior sends the proposal for dissolution to the corresponding tribunal, which analyzes the authorities’ responsibilities and eventually declares ineligibility and proceeds to prosecute those responsible.56 Politicians found guilty may not participate in the subsequent two elections that take place after the dissolution.[/mfn] It continues to be an administrative mechanism that does not substitute the eventual criminal proceedings that can be taken by the Prosecution Service. In any event, the ineligibility for standing for office is not automatic.

It is important to highlight the fact that the ex-public officials who were involved in these dissolved governments can begin an appeals process against the decree.57 As such, local public officials are not defenseless against a mechanism that depends fully on the national authorities.

Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry

Although this is not a mechanism in itself, it is useful to review the recent “Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into the Phenomenon of Intimidation toward Local Administrators”.58

In 2013, the Italian senate authorized the creation of this commission, which is presided over by Senator Doris Lo Moro, to investigate acts of violence – including those not linked to criminal organizations – against local public officials, in addition to proposing legislative proposals and administrative solutions to allow them to freely exercise their functions. The final report provided a detailed overview of the phenomenon of intimidation, the range of underlying motives, and the different ways in which it manifests itself. For example, in 2013, a mayor in the province of Lombardy was shot by a policeman who had been suspended after being found guilty of fraud and embezzlement.

Furthermore, in the region of Emilia-Romagna, local officials referred to smear campaigns on social networks as being the most common method of intimidation. Although the report states that the judicial authorities may not consider it as such, it goes on to say that this is a phenomenon that requires attention given the effects it has on the relationships between public officials and voters.

In 2017, Italy created an observatory that compiles, on a permanent basis, statistics about local administrators who receive threats and are subject to violence. The observatory acts as a liaison between local administrators and the government.

Among the measures recommended by the Commission, there is a focus on increasing the presence, physical and otherwise, of national institutions in local administrations, in addition to the adoption of territorial control and prevention programs by the police. Furthermore, it recommended amendments be made to the Penal Code, which were accepted by the Italian parliament in 2017. Another innovation was the creation of an observatory that compiles, on a permanent basis, statistics about local administrators who receive threats and are subject to violence. The observatory acts as a liaison between local administrators and the government, for example, to share solutions that consolidate protection tools and support administrators who report acts of intimidation.59 It is also tasked with training local officials regarding prevention and support campaigns, in addition to the possibility of activating, in the capital’s regional prefectures, similar courses aimed at administrators.

This initiative is interesting with regard to the discussions about Mexico for at least three reasons:

-1- The co-responsibility of the legislative and judicial powers in addressing this phenomenon.

-2- The relevance of compiling empirical evidence to draft public policy.

-3- The consideration of other intimidating or violent actors, apart from the mafia, that could affect electoral processes and the functions or legitimacy of local governments. It is important to highlight the fact that the members of the commission determined that, between 1974 and 2014, of the 132 local politicians who were assassinated, 47% were victims of organized crime. This figure is considered to be too high.60This means that the data invalidates the possibility of a one-dimensional argument regarding violence (e.g., “the organized crime party”; “they kill each other”).

Notes

- General Law of Electoral Institutions and Procedures, published in Mexican Official Gazette on May 23, 2014. ↩︎

- Prior to the reforms attributable to the transition to democracy, it is possible to find indications of candidate protection measures; however, these were not formal. For example, in the 1950’s, the recently created Auxiliary Police Force in Mexico City offered protection to candidates, as well as at party buildings or polling stations (Martínez Trujillo, 2019). ↩︎

- Published in the Mexican Official Gazette on August 15, 1990. ↩︎

- Published in the Mexican Official Gazette on February 12, 1987. ↩︎

- The Presidential General Staff (EMP) was a military and technical body whose fundamental mission was to protect the president, his family, the secretaries of State, and other individuals who, given their mandate or situation, were designated by the executive branch. With more than 2,000 military personnel, 9 aircraft and 8 helicopters at its disposal, it also provided security and comprehensive logistical support to protection foreign dignitaries during their visits to Mexico. Its mission was also to coordinate comprehensive logistical and security support for international meetings involving heads of state and government, as well as ministerial-level meetings organized by the Federal Government. ↩︎

- Mexican Senate, Disbanding of the Presidential General Staff, Bulletins, May 2, 2019. ↩︎

- Published in the Mexican Official Gazette on January 9, 2006. ↩︎

- Federal Electoral Institute, Council Agreements, Extraordinary Session held on January 14, 2009. ↩︎

- COFIPE 2008. ↩︎

- Federal Electoral Institute, “AGREEMENT OF THE COUNCIL OF THE FEDERAL ELECTORAL INSTITUTE TO ESTABLISH INSTITUTIONAL POLICIES FOR THE FILING OR REFERRAL OF COMPLAINTS AS A RESULT OF THE PROBABLE COMMISSION OF CRIMES RELATING TO THE 2008-2009 FEDERAL ELECTORAL PROCESS, THE REQUEST FOR SECURITY MEASURES FOR CANDIDATES, AND THE CONSOLIDATION OF COLLABORATION AGREEMENTS WITH DIFFERENT AUTHORITIES”. ↩︎

- Database Noria-MXAC on political and electoral violence in Mexico, 2021. ↩︎

- Newsroom, “Poiré admits interference of organized crime in electoral processes”, Proceso, January 6, 2012. ↩︎

- Camarena, S., “PRI candidate for governorship of the State of Tamaulipas is shot and killed”, El País, June 29, 2010. ↩︎

- Calderón, L. M., Interview with María Teresa Martínez Trujillo. March 18, 2014. ↩︎

- Zepeda, M. “Organized crime threatened candidates in 18 municipalities in Michoacán”, Animal Político, December 2, 2011. ↩︎

- Martínez, F., “IFE public security indicators plummet”, La Jornada, March 11, 2012. ↩︎

- Rueda, R., “From 2008 to 2015, violence has left 30 candidates dead”, El Financiero, April 11, 2016. ↩︎

- NTX, “Government will safeguard elections in Guerrero”, Informador Mx, January 16, 2011; Muñoz, A.E. and León, R., “Signing of Security Agreement for BCS”, La Jornada, February 4, 2011; Newsroom, “Coahuila and the Secretary of State sign protocol to guarantee election security”, Territorio de Coahuila y Texas, May 30, 2011; Newsroom, “Nayarit Signs Electoral Security Agreement”, La Jornada, June 28, 2011; Magallanes, J., “Blake Signs Security Protocol with Governors of Hidalgo and Mexico State”, MVS Noticias, May 6, 2011. ↩︎

- Marín, L., “Blake Defends Security Protocols”, W Radio, November 4, 2011. ↩︎

- Calderón, L. M., 2014, op. Cit. ↩︎

- Macías, V., “IFE and SEGOB drive coordination to protect candidates in 2012”, El Economista, December 18, 2011. ↩︎

- Ureste, M., “PRI candidate found dead in Chihuahua”, Animal Político, June 12, 2013. ↩︎

- Newsroom, “Candidate for Valle de Chalco seat assassinated”, El Economista, June 2, 2012. ↩︎

- Aguilar, R., “PRI mayoral candidate for Chilapa is assassinated”, Excelsior, May 2, 2015. ↩︎

- Etellekt Consultores, Seventh Report on Political Violence in Mexico, (Mexico City: Etellekt, July 9, 2018). ↩︎

- After an amendment was made to Article 41 of the Constitution to standardize local and federal criteria, on April 4, 2014, the IFE was dissolved, paving the way for the creation of the INE. Among its new functions was the organization of federal elections and collaboration in local elections, in addition to oversight of the resources of each political party throughout the year. ↩︎

- INE, “SEGOB and INE present Personal Protection Protocol for presidential candidates”, Central Electoral, April 18, 2018. ↩︎

- SEGOB, “Personal Protection Protocol for presidential candidates”, YouTube, April 4, 2018. ↩︎

- General Law of Electoral Institutions and Procedures, op. Cit. ↩︎

- Statements made by the Secretary of State on his Twitter account. ↩︎

- Rivero, M. I., “IAHCR observes violence during electoral process in Mexico”, Press Release 102/18, May 10, 2018. ↩︎

- Ballinas, V., “SG: action will be taken in light of any acts of violence during the elections”, La Jornada, May 14, 2018. ↩︎

- Operativo Escudo-Titán was deployed by SEGOB on January 29, 2018, with the goal of decreasing crime levels in a number of areas deemed to be violent. It was based on serving a large number of arrest warrants. For information about its results and limitations, please see Gallegos, J., “Operativo Escudo Titán”, Animal Político, May 24, 2018; Mexican Secretary of State, “Message from the Secretary of State, Alfonso Navarrete Prida”, Press Release, May 27, 2018. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- General Law of Electoral Institutions and Procedures, op. Cit. ↩︎

- Urrutia, U., “Elections in Mexico, the most violent in recent history according to observers”, La Jornada, August 23, 2018. ↩︎

- President of Mexico, “Presentation of plan to prevent political violence during the elections on June 6”, Bulletin, March 4, 2021. ↩︎

- President of Mexico, op. Cit. ↩︎

- López Obrador, A. M., “Presentation of Candidate Protection Report; “let the people choose freely”, reaffirmed the President”, April 30, 2021. ↩︎

- Trejo, G. and Ley, S., “Towns under fire (1995-2014)”, Nexos, February 1, 2015. ↩︎

- Mendoza, A., “Political and electoral violence in the 2018 elections,” Alteridades, Vol. 29, No. 57 (2019), pp. 59-73. ↩︎

- Mexican Government, National Public Security Strategy. ↩︎

- On April 30, the Minister stated that 65 candidates were being protected: 40 of them by state police, 17 by the National Guard, and 8 by local police, the FGR, or the SSPC and the Ministry of the Navy combined. Further information from López Obrador, A. M., op. Cit. ↩︎

- García, J. “Opposition governors in Mexico break from federal government”, El País, September 7, 2020. ↩︎

- López Obrador, A. M., op. Cit. ↩︎

- Espinosa, V. “Elections in Guanajuato: When security problems hit untenable levels”, Proceso, May 14, 2021. ↩︎

- Morán Breña, C., “The assassination of Abel Murrieta, electoral candidate and lawyer for the LeBarón family massacre”, El País, May 13, 2021. ↩︎

- The Tamaulipas State Electoral Law, published in the official state newspaper (POE) on June 13, 2015. ↩︎

- Ley, S., Violence and Citizen Participation in Mexico: From the Polls to the Streets, (San Diego, California: University of San Diego, Justice in Mexico Project, 2015). ↩︎

- Daniele G. and Dipoppa G., “Mafia, Elections and Violence Against Politicians”, Journal of Public Economics, 154 (2017), pp. 10–33. ↩︎

- Di Cataldo M., Mastrorocco N., “Organised Crime, Captured Politicians and the Allocation of Public Resources,” TEP Working Paper No. 1018 (2019), Trinity Economics Papers, Department of Economics. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Occhiuzzi, F., “The Dissolution of Municipal Councils due to Organized Crime Infiltration,” European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, Vol. 5, Issue 2 (2019), pp. 45-53. ↩︎

- Calderoni, F., y Di Stefano, F., “The Administrative Approach in Italy”, in Administrative Measures to Prevent and Tackle Crime, eds. Spapens A.C.M., Peters, M., y Van Daele, D., Eleven, International Publishing (2015), pp. 239-264. ↩︎

- Article 143 of Legislative Decree 267 in 2000, Testo Unico degli Enti Locali (TUEL). ↩︎

- Occhiuzzi, op. Cit. ↩︎

- Avviso Pubblico, “SCIOGLIMENTO DELLE AMMINISTRAZIONI LOCALI PER INFILTRAZIONI MAFIOSE E SUCCESSIVA INCANDIDABILITÀ: SINTESI DELLA NORMATIVA”, December 2018. ↩︎

- Avviso Pubblico, “AMMINISTRAZIONI SCIOLTE PER MAFIA: DATI RIASSUNTIVI”, April 30, 2021. ↩︎

- Lo Moro, D., Gualdani, M., Zizza, V., Cirinnà, M., Commissione Parlamentare d’inchiesta sul fenomeno delle intimidazioni nei confronti degli amministratori locali. Final Report, Session held on February 26, 2015, Italian Senate; UPI Newsroom, “Osservatorio Atti Intimidatori contro Amministratori locali”, June 23, 2020. ↩︎

- Occhiuzzi, op. Cit. ↩︎