The Jordan Compact was designed to pioneer a new, hybrid modality of emergency response and developmental aid. Much has been written about its financial aspects and its impact on work opportunities for Syrians. But what about its influence on European market access for Jordanian companies?

Introduction

As is the case everywhere else, Jordanian politics has long turned on questions of economics. Recent contentious episodes well attest to this fact: 2018 saw protests erupt over proposed changes to the tax code, 2019 saw street actions prompted by the introduction of austerity measures, and 2020 and 2021 saw the Teachers’ Syndicate organize a lengthy fight for better wages. With 25%1 of the population already unemployed, debt repayment obligations demanding a combination of tax hikes and spending cuts, and the Covid shock still reverberating across the economy, there is every reason to believe these events are but a precursor of what is still to come.

In circumstance so tense to begin with, the enormous populations of Syrian refugees which came to settle in Jordan—some 650,0002 between 2011 and 2016—was bound to become a political football. As it played out, it was not long before these populations, initially welcomed as “brothers” and “neighbors”, came to be viewed as undesirables—as burdens absorbing scarce resources.3

Aware of this, the European Union and members of the broader international community attempted to ease some of the pressures introduced by Jordan’s absorption of Syrian refugees. Efforts were organized through 2016’s London Conference, where a program—referred to as the Jordan Compact—was developed.

In design and self-concept, the Jordan Compact aimed to combine and synthesize two aspects of international aid that, until this point, had never been brought together before: a humanitarian emergency response (targeted at supporting Syrian refugee populations) and a development package (targeted at supporting the host communities and Jordanian economy writ large).

As expressed in the official language of the Jordanian state, the goals of the Jordan Compact are as follows: “1. Turning the Syrian refugee crisis into a development opportunity that attracts new investments and opens up the EU market with simplified rules of origin, creating jobs for Jordanians and Syrian refugees whilst supporting the post-conflict Syrian economy; 2. Rebuilding Jordanian host communities by adequately financing through grants to the Jordan Response Plan 2016–2018, in particular the resilience of host communities; and 3. Mobilizing sufficient grants and concessionary financing to support the macroeconomic framework and address Jordan’s financing needs over the next three years, as part of Jordan entering into a new Extended Fund Facility program with the IMF”4.”

The agreement 5 itself comprises several elements: $1.8 billion in pledges to support the Jordan growth plans and a UK commitment of $250 million to underwrite a World Bank loan, support to education programs, and an economic collaboration based on a relaxation by the EU of the rules of origin for Jordanian exports.

Five years on, few reports or analyses have been published that adequately evaluate whether 6 the Jordan Compac achieved twhat it set out to do. Almost all observers have agreed, however, that the intervention was a gamechanger of sorts, one that saw “Jordan… effectively become the model for refugee compacts, providing important lessons learned on which to build subsequent iterations in other protracted displacement contexts.”7

This article aims at determining whether the hype around the Jordan Compact is warranted. It does so by honing in on the effects of one of its more underresearched aspects: namely, those initiatives that were meant to benefit Jordanian companies through facilitating export-oriented activities.

To explore this subject matter, fieldwork was undertaken by the author of this report during 2019 and 2021. In 2019, this entailed conducting interviews with executives of companies registered to participate under provisions established by the Jordan Compact, executives of companies not registered to participate, officials from the European delegation in Amman, and members of the Jordanian Chamber of Commerce. In 2021, some of these same interlocutors were contacted for follow-up interviews by the author of this report and Zaid Awamleh, Research Assistant of the Migration Governance and Asylum Crises Program (MAGYC).8 Mr Awamleh interviewed five company executives, an employee of the Ministry of trade, and a Syrian employee of one of the firms in question. It should here be stated that any claims made henceforth do not reflect Mr. Awamleh and MAGYC’s positions as they had no involvement in the design of this research, analytical process or in the writing of this article.

From the “refugee rentier state” to specific economic measures

Financially speaking, the Jordan Compact mobilized a wide and diverse range of grants and loans. In view of the moneys involved, many scholars appropriately directed their attentions toward evaluating how these capital injections interacted with the rentierist political economy traditionally maintained by the Hashemite regime. After conducting such an investigation, Gerasimos Tsourapas went so far as to contend that the Jordan Compact functioned to finance a new formation he calls the “refugee rentier state.” As he posits, the arrangement represented a mechanism by which the Hashemite regime could leverage its role as refugee “shock absorber” to extract material and diplomatic benefits for itself.

Though doing important work by highlighting the political economy of migration, one can dispute the merits of the arguments that have been put forth by Tsourapas and like-minded scholars such as Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar and Rawan Arar, as I do in an article set to be published in 2022. More importantly, whether those scholars were ultimately justified in making their claims not, their analyses still leave a number of critical questions unanswered. None such question is more salient than whether the Jordan Compact—regardless of its effect on the regime itself—had a positive social and developmental effect for the population at-large.

In order to gain traction on these matters, one must first be made familiar with the precise economic objectives that EU officials had in mind while negotiating the Jordan Compact. Reduced to their simplest form, these objectives were dual: (i) to improve the labor market outcomes of Syrian workers in Jordan and (ii) to do so through boosting the prospects of export-oriented firms operating in particular sectors of the Jordanian economy.

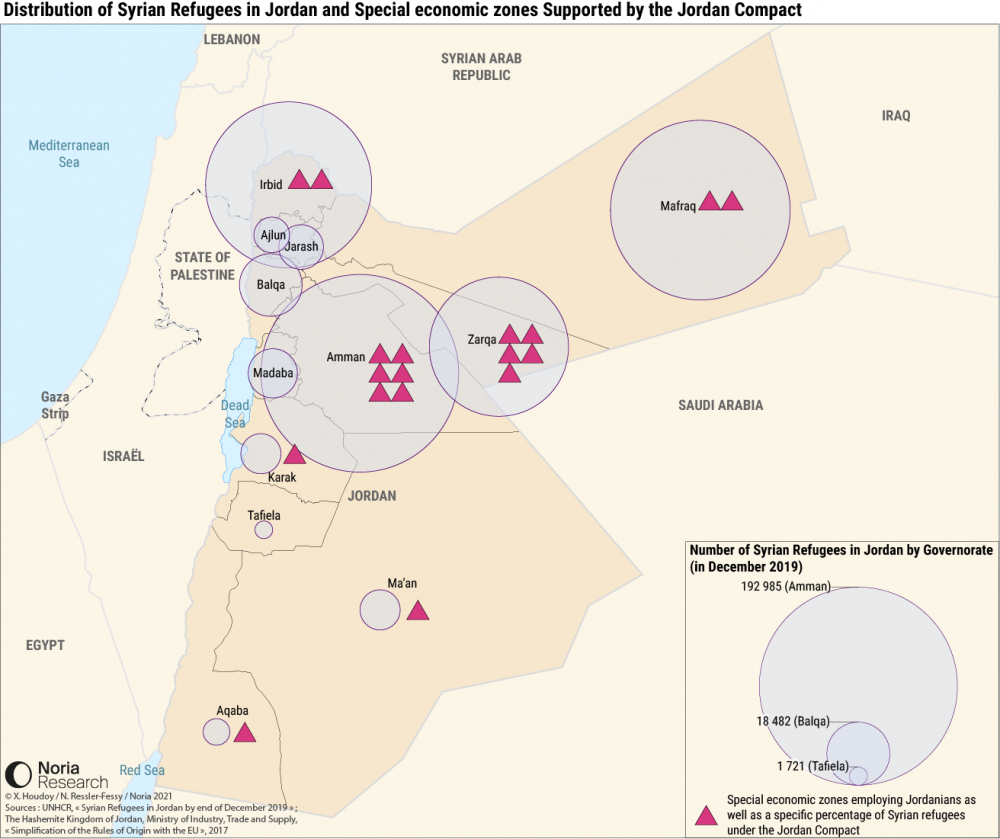

In service of these ends, the EU and IMF made the release of the variety of loan and grant facilities contained within the Jordan Compact contingent upon Jordanian policymakers agreeing to provide 200,000 work permits to Syrian refugees. Note that the permits extended were not to be of universal validity, but specific to the agriculture, construction and manufacturing sectors of the economy. So to incentivize firms operating in the manufacturing sector in particular to hire Syrian refugees, the Jordan Compact also installed conditional provisions related to EU market access. Specifically, it made firms that could satisfy two criteria—(i) the employment of a labor force at least 15% comprised of Syrian workers and (ii) the running of business operations within one of Jordan’s Special Economic Zones—eligible to export goods to Europe without having to meet rules of origin requirements.

Evaluating the Jordan Compact: Jobs and Export Effects

Despite good intentions, the Jordan Compact did not deliver the outcomes that its designers hoped for. The program’s underperformance can be attributed to a number of variables.

The first is policy design. As mentioned, the Jordan Compact sought to improve Syrian labor market outcomes principally through facilitating their access to sector-specific work permits. This was a problematic tact to take in two regards: to begin, it assumed that the possession of a work permit would alone be sufficient to secure a job seeker employment, a rather absurd notion in view of contemporary unemployment and labor force participation figures in Jordan. It also ignored the fact that employment within the sectors targeted by the program—agriculture, construction and manufacturing—tends to be informal in nature. The latter being the case, securing work permits for Syrian refugees in these sectors was bound to have a marginal effect on their job prospects. Finally, there was the matter of the incentive structure on the employer side of things. Per the original terms of the Jordan Contract, broadened access to the European market was conditional upon a firm both employing Syrians and operating out of a special economic zone (SEZ). The country’s SEZs, however, were located nowhere near the main Syrian population centers. Though firm location was eventually removed from eligibility criteria related to EU market access—as were provisions demanding that employers’ eventually scale up the Syrian portion of their workforce to 25%— the damage was, by that point, already done. All in all, a mere seventeen companies would wind up able to take advantage of the export opportunities furnished under the Jordan Compact. 9

Project implementation also proved to be littered with issues. Work permit distribution processes were muddled and ineffectual. By 2018, only 120,000 work permits had been given out, which represented a mere 60% of the figure officially targeted two years prior. Worse, only 42,000 of those with work permits had managed by that point to secure formal employment.10

Program implementation floundered when it came to supporting firms as well. Many firms that participated in schemes meant to trade expanded access to the EU market for the hiring of Syrians reported receiving little help or guidance as pertained to actually finding export opportunities inside of Europe. As a business owner of a detergent and medical sanitizer company put it in an interview in July 202:

“To be able to compete in the EU market, there should be up-to-date studies of what is an available market, the prices, the user’s culture, and so on. We lack such studies. I believe that there should be organizations offering that kind of study to the exporters.” Nor was there any effort taken to help firms overcome the traditional blockages—principally high tax rates and high shipping and storage costs—impeding export-oriented activities.11

Cui Bono?

All its problems notwithstanding, there were still some companies who came to benefit from the Jordan Compact. The lack of transparency around program participants and export-related data of course makes drawing hard conclusions on this subject a fraught undertaking. Nevertheless, information gathered through fieldwork does allow us to posit the claim that the biggest gainers from relaxed rules of origins-related incentives tended to be older, larger, and traditionally export-oriented firms. This outcome seems to be a function not only of such firms being a natural fit with the program’s designs, but of their positioning within social networks and their knowledge of sites of power.

Such a hypothesis is lent considerable credence by the testimony of different business executives. Those who knew their way around ministries and Chambers of Commerce found the Jordan Compact to be a wonderful and skilfully administered program. As one such individual put it:

“Personally, I have very good relations with the Chamber of Commerce. Honestly, these people are working very hard to keep us updated on any useful information regarding our businesses. They do have great communications with the companies, either by phone, email, or their social media platforms. We honestly owe them a thank you for all their efforts. (…) The ministry of trade and finance played a great role in helping in the registration process. They really made things easy for us.”

In contrast, those from outside the commercial elite and thereby less familiar with the senior levels of the bureaucracy found the Compact to be alienating and impossible to navigate. As an executive in the very same business as the one quoted above described, “After finishing the registration (for relaxed rules of origins benefits), we didn’t hear back from them. Not even any reports about the EU market that would have been so useful and relevant to our work”. Interviews with a number of other executives from firms with little pre-existing experience in exporting to Europe suggest the grievances of this particular businessman to be generalizable. Their disappointment with the Jordan Compact is perhaps best summed in the following quote spoken by another company executive involved in the relaxed rules of origin initiative: “As a company, we feel neglected and we cannot be open to the global market by ourselves.”

Conclusion

All in all, the Jordan Company largely failed to jumpstart exports and generate the employment gains it set out to. To some extent, it also reinforced existing fractures within the business classes, benefiting connected and established actors while offering little to those outside elite circles.

Should such an initiative be tried again in the future, it is imperative that more concern be paid to both program design and program implementation. On the firm side of things, it will also be critical that efforts be taken to better link young, less experienced and less socially and politically connected companies to the benefit regime being provided. By drawing such entities into the program design process itself and directly helping them navigate the challenges of the export business, the yield on the EU’s investment could be greatly enhanced.

The project relies on a partnership between Noria Research, Sine Qua Non and the French Institute of the Near East (IFPO). It benefitted from the financial and research support of the French Institute of the Near East, a first peer-review by Sine Qua Non and a full edition and peer-review support given by Noria Research.

Bibliography

- “Unemployment rate hits 25%- DoS” The Jordan Times, June 2021 (link)

- Arar, Rawan. 2017. “The New Grand Compromise: How Syrian Refugees Changed the Stakes in the Global Refugee Assistance Regime”, Middle East Law and Governance, 9(3), 311

- Cuéllar, Mariano-Florentino. 2006. “Refugee Security and the Organizational Logic of Legal Mandates”, Working Paper, Georgetown Journal of International Law, Stanford Public Law, 37 (918,320), 1–102

- Empociello, to be published. “The thickness of the Syro-Jordanian borderland”. In Dorai, Kamel and Dallal, Ayham. Camps in the Middle East

- Huang, Cindy ; Gough, Kate, 2019. “The Jordan Compact: Three Years on, Where Do We Stand?”, Center for Global Development (link)

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Support to the middle East and North Africa (MENA) Jordan’s Statement from the London Conference on “Supporting Syria and the Region” held on 4 February 2016 (link)

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos. 2019. “The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Foreign Policy Decision-Making in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey”, Journal of Global Security Studies, 4(4), 464–481.

- Tsourapas, G. (2020) The Jordan Compact, Working paper, MAGYC (link)

- Decision n°(1)2018 of the EU-Jordan association committee, 4/12/2018.of the EU-Jordan association committee, 4/12/2018.

Notes

- On the first quarter of 2021, “Unemployment rate hits 25%”, DoS The Jordan Times ↩︎

- This number draws from the UNHCR official number, with counts 650,000 individuals. Jordanian authorities claim hosting up to 1.5 million Syrian refugees. ↩︎

- But also potential security threat after the terrorist attack targeting border guards that happened in 2016. See Empociello, to be published. “The thickness of the Syro-Jordanian borderland”. In Dorai, Kamel and Dallal, Ayham. Camps in the Middle East. ↩︎

- Government of Jordan, 2016 ↩︎

- https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/jordan-compact-three-years-where-do-we-stand ↩︎

- https://www.cgdev.org/blog/jordan-compact-three-years-on ↩︎

- https://www.cgdev.org/blog/jordan-compact-three-years-on ↩︎

- This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 822806. ↩︎

- The official document amending the Jordan Compact in 2018 declared that only eleven companies had to date been registered for relaxed rule of origin benefits, with only a handful amongst them having managed to export any actual output. By 2021, registered companies jumped to seventeen, though only eleven had successfully exported products to Europe. ↩︎

- Decision n°(1)2018 of the EU-Jordan association committee, 4/12/2018 ↩︎

- As one executive in the hygienic paper business described these blockages: “We pay a lot of taxes in Jordan as a manufacturing industry. In addition to our commitment to paying the workers, we also pay a lot for storing our products before exporting through Aqaba harbour. Adding to that, the regular bills of energy, electricity, and water.” ↩︎