Interview with Fernando Garlin Politis, conducted by Yoletty Bracho

Could you give us a quick overview of Venezuelan migration in Latin America? More precisely, what is the immigration policy toward Venezuelans in neighboring Colombia?

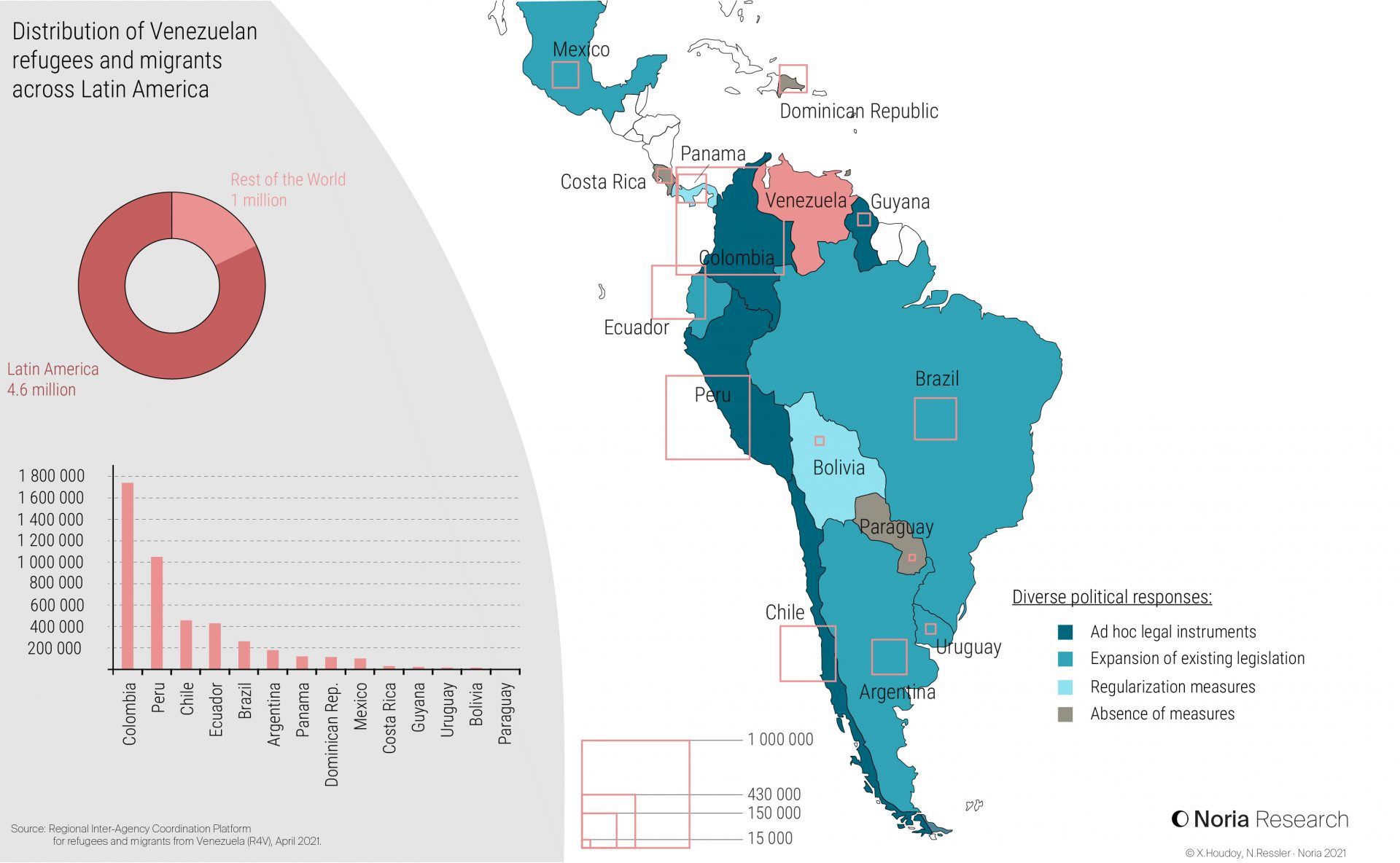

In less than six years, Venezuelan migration has become the largest exodus in contemporary Latin American history and the second largest in the world after the Syrian exodus. To cope with the mass arrival of Venezuelans, most South American countries have adopted policies to control and organize migration flows. For instance, “humanitarian” or “democratic” visas have been issued to regularize Venezuelans’ immigration status in Ecuador, Chili, and Peru. Compared to the sensational policies of forced return and deportation of refugees at European and American borders, these restrictions are more subtle, and their divisive, marginalizing effects on the populations are less obvious.

To address this mass immigration, the Colombian government has implemented a two-stage policy toward Venezuelans. The first stage began in 2018 and continued until January 2021: over that period, official rhetoric promoted a policy of “integration through work.” The second stage began on February 8, 2021 and could be described as a “humanitarian integration” policy, promising the regularization of 1.7 million undocumented Venezuelans through a “temporary migrant protection status.” Since the second stage is still very recent, I will focus in this interview on the effects of the “integration through work” policy, and of its disruption during the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, on the experience of Venezuelan refugees.

In 2018, Special Stay Permits (PEP in Spanish) were made available to Venezuelan refugees. They granted Venezuelan citizens temporary residency for 90 days, with the possibility of an extension of up to two years. Those Special Stay Permits were free, but could only be issued upon the presentation of a valid passport, which in practice excluded a large number of refugees. In fact, Venezuelans must sometimes wait up to a year to receive a passport through the official channels. Many of them, under time pressure, sometimes have to give bribes of as much as USD$2000 to administrative clerks to accelerate the process. Since a lack of economic resources is usually one of their main reasons for leaving their country in the first place, these backdoor methods for obtaining passports are often out of reach for people whose financial situation is already precarious. As a consequence, they are forced to take out loans and arrive in Colombia in even worse financial shape.

Once the Special Stay Permits expired, there was no procedure in place for acquiring permanent residency in Colombia. This restriction had serious consequences on the lives of Venezuelan refugees. Indeed, as Venezuelan organizations in Colombia point out, it is already very difficult for them to open bank accounts, obtain employment contracts, enroll in universities, or receive recognition for their professional experience. Because of these issues, especially the last, many refugees end up working in the informal sector, for instance as street vendors selling coffee and candy.

This situation was aptly described by a representative of an international humanitarian organization at an academic forum attended by officials from the Colombian Ministry of Labor. “Venezuelans can only work the jobs that Colombians no longer want: garbage collection, street cleaning, heavy manual labor in factories and in other sectors,” he said. This seems to contradict the official narrative of so-called “integration through work.”

As immigration policies are tightened, one can assume that the COVID-19 pandemic has still further restricted refugees’ migration experiences. Could you tell us to what extent immigration policies have been affected by the pandemic, and what impact lockdowns have had on Venezuelan refugees?

The Covid-19 pandemic has put Colombian immigration policy toward Venezuelan refugees to the test. Borders were closed on March 14 and a lockdown was imposed a week later, lasting until August 31, or for more than five months. Those measures limited commercial activity, the only source of income for much of the Venezuelan community: according to the National Statistics Office (DANE), 90% of Venezuelans work in the informal sector. In addition, most refugee support centers and shelters for indigent Venezuelans were forced to close.

Under these circumstances, economic insecurity and the lack of protection for Venezuelan refugees in Colombia were being felt more acutely than ever. Once more, the limits of the “integration through work” policy were exposed, along with the discreet refoulement practices that it entailed. Indeed, Venezuelan refugees’ fear for their own safety and increasingly dire financial straits led some to return to their home country.

According to Colombian statistics, 2.35% of Venezuelan refugees in Colombia returned home in 2020. For now, this trend is still limited in scope, since before restrictive measures were imposed to curb the pandemic, the number of Venezuelans coming to Colombia had kept increasing: they rose by 62% from 2017 to 2018, and by 39.45% from 2019 to 2020. These figures should also be read in conjunction with the stories of thousands of Venezuelan “caminante” (walker) families, who cross the border illegally every day in spite of the strict travel restrictions.

Who are those refugees who decide to go back home, and how do they prepare for this journey, both financially and emotionally?

Through interviews conducted remotely, due to access and travel restrictions, I was able to identify two main categories of Venezuelans who return home.

The first category, less common, is comprised of lower-middle-class immigrants originating from impoverished suburbs, who return permanently to Venezuela for three main reasons. First, these people have homes in Venezuela, something they do not always manage to find in Colombia; back in Venezuela, they often own a family house or apartment. Secondly, faced with two situations of equal uncertainty, they believe they would have more possibilities to get by in their home country. The third reason is the discrimination that they suffer in Colombia, and the impression of being treated like “beggars.” Based on the interviews, it appears that this group of migrants, equally downgraded in Venezuela and in Colombia, tends to return because of economic and family ties.

The second category represents the majority of migrants who go back to Venezuela. They are working-class people from rural areas and the suburbs of small towns. They return home to better prepare for their next journey; as Franklin puts it, the idea is to “immigrate home for now, in order to go back abroad later.” The people in this group generally had a very difficult first experience of emigration, without documents or familiarity with the legal procedures necessary to obtain a residency permit in Colombia. As a result, many fell victim to scams when attempting to legalize their status by buying an identity card or Special Stay Permit.

This group of refugees often decided to emigrate following a specific event, such as the murder of a relative; food, water, and power shortages; lack of medication in hospitals; and so forth. They then set off on a long journey, most of them on foot. They describe learning to “survive” in a variety of perilous situations, and they are willing to undertake the journey multiple times in the unwavering quest for a better life.

Your work with these groups of refugees shows that their return is difficult and the outcome far from guaranteed. How are they received in Venezuela, given the current health crisis? Why do some of them choose to stay, while others prepare to leave again?

Once migrants begin their journey back to Venezuela, their experiences greatly depend on the quality of their social connections. For instance, Yolanda is a refugee who went back to Venezuela for good after living in Colombia for two years. Her story illustrates the hardships that Venezuelans must face as they return home in the midst of the pandemic.

Yolanda grew up in the suburbs of Caracas, where she worked in a hair salon. She decided to emigrate to Colombia when some friends offered her a position as a mobile hairdresser in the border city of Cúcuta. She had to stop working when the lockdown was announced. With no prospects of economic stability in the short term, and no support from the people she knew in Colombia, she chose to go back to Venezuela, where she decided that she would sell perfumes that she had used her savings to buy to make ends meet.

Yolanda’s journey back home began in Cúcuta, where she put her name on a waiting list to cross the border through a humanitarian corridor. After 17 days, Yolanda learned she might still have to wait another two weeks, and since she was nearly out of money to support herself, she called her cousin, a member of the Venezuelan armed forces, for help. He pulled a few strings in the Colombian border control agency to allow Yolanda to cross the border two days later. This example shows that border outcomes often hinge on unofficial communications between Venezuelan and Colombian state agents.

Yolanda’s ordeal did not end on the other side of the border. She was first transferred to one of the “shelters” set up by the government to restrict the movements of returning Venezuelans in order to stop the spread of the virus. These centers are known as Integrated Social Services Points (PASI in Spanish). She was then transferred to a sports-facility-cum-holding-center monitored by soldiers during daytime.

The “refugees” were forced to remain in the makeshift shelter until they tested negative for Covid-19. After leaving this second shelter, Yolanda was transferred to a school, where she spent nine days. Having gained the trust of the school’s chief security officer by informing him about two women who were about to give birth and needed urgent evacuation, she was allowed to leave soon thereafter.

Yolanda further recounts that upon arriving in Caracas, she was inexplicably “allowed to go free,” unlike several of her acquaintances, who were placed in a hotel by the government for 21 days as a preventive (and excessive) measure. Now, after a 58-day journey, Yolanda asserts that she is back for good, although she keeps in touch via WhatsApp with refugees whom she met in the shelter at San Antonio del Táchira. They have invited her to return to Colombia with them as soon as the borders reopen. But Yolanda has decided to stay, saying that she loves her country, even though life is hard and she feels like an outsider now.

There are seemingly two reasons for Yolanda’s decision: first, she is anxious about the debt she incurred in Colombia in order to support herself; and secondly, she claims that she prefers to scrape by in a city where she can give her daughters a home, which is easier for her in Venezuela than in Colombia. However, in the end, she says that she would be ready to leave again, “if it is in God’s plan.”

In learning about these difficult and sometimes dangerous experiences, one wonders about the impact they must have on refugees. Can you tell us more about the subjectivity of the refugees that you interviewed?

In studying Yolanda’s and other refugees’ journeys during the pandemic, I observed the effects of these experiences on the ways in which they define their objective needs, i.e., food, shelter, and healthcare; their subjective needs, including legitimacy and the feeling of being taken into account; and their capacity to interact with public and international authorities to fulfill these needs. Pervasive in Yolanda’s story is a feeling of detachment caused by her forced return to Venezuela. Her ordeal as a refugee, along with the immobility imposed by public health measures in both countries, emphasizes how little protection she expects from both national and international authorities. This type of subjective experience prevents refugees like Yolanda from viewing themselves as right-holders, and therefore discourages them from applying for the protections that are available to them.

The experience of migration also has a significant impact on migrants’ attitudes toward their future. Many of the refugees who return to Venezuela no longer dream of improving their situation. Their hopelessness has been exacerbated by the pandemic; returning refugees, largely criminalized by the Venezuelan government, often feel excluded in their own country. One of my interviewees aptly put this feeling into words: “I’m not asking anything of anyone,” he said. “I don’t want to be given anything. I just want to have something to do and to be paid, anywhere, so that I can eat.”

Thus, subtle refoulement practices have become more visible on both sides of the border during the COVID-19 pandemic, alienating refugees from the social and health protections of both states.

Further Readings:

- Eduardo Domenech. “”Las migraciones son como el agua”: Hacia la instauración de políticas de “control con rostro humano””. Polis [online], 35 | 2013