The USSR’s collapse in 1991 gave rise to various conflicts and tensions amongst the young states which emerged from the Soviet Union. In Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, a consensus was formed not to question the borders stemming from the Soviet period. Only four cases depart from this rule: Abkhazia, South Ossetia, High-Karabagh and Transnistria, a controversial territory situated along Moldova’s Eastern border, between the Dniestr river and Ukraine.

Derived from the Latin word Transnistria meaning «beyond the Dniestr», this word is contested by the Tiraspol authorities who named the territory Pridnestrovskaia Moldovskaia Respublica or Pridnestrovia in the 1995 constitution. Transnistria appears in its present form for the first time in 1924 under the name of Soviet Socialist Autonomous Republic of Moldavia (SSARM) and was tied to Bessarabia in 1940 during its annexation by Stalin’s USSR

During the Perestroïka, at a time when nationalism was rising in Moldavia, the non-Moldavian majority territories claimed their independence in order to maintain their status of republics integrated within the Soviet Union. Primarily inhabited by a Turkish-speaking orthodox minority, Gagauzia did not continue in this direction with the end of the Soviet empire and instead opted for the status of an autonomous region within the Moldavian state. On the contrary, Transnistria, mainly populated by Moldavians but also by Russians and Ukrainians, declared its independence in September 1990.

This declaration triggered an armed conflict between the secessionist province and Moldova’s army until 1992, when Russia’s 14th army intervened in favour of Transnistria. Since then, the conflict has remained frozen and a buffer force made up of Russian, Moldavian, Ukrainian and Transnistrian soldiers has been guaranteeing the respect of the ceasefire between the different parties.

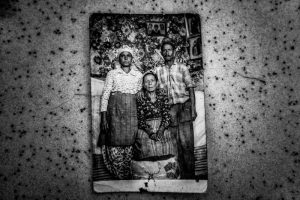

Julien Goldstein went to Transnistria in 2002, two decades after the signature of the ceasefire. His photographs illustrate a situation that has enabled the Tiraspol regime to constitute a de facto state with its administration, its flag and its coat of arms clearly reclaiming a Soviet heritage. Throughout the years, the Transnistrian authorities have developed a national narrative to legitimise the province’s independence1. It is thus described as a land of historical mixture between populations having a shared attachment for the Russian neighbour and the Soviet past. In December 2011, Evgueni Chevtchouk won the presidential elections, putting an end to Igor Smirnov’s decade-long rule. However, even though there are notable differences between the new president and his predecessor, and talks have resumed last November, the frozen conflict between Moldova and the secessionist province of Transnistria is still a long way from being resolved.

Notes

- Florent Parmentier, « La Transnistrie, politique de légitimité d’un Etat de facto», Le Courrier des pays de l’Est, 2007/3 n° 1061, p. 69-75 ↩︎