This article is Chapter 4 of Noria MXAC “Violence Takes Place” Editorial Series.

Introduction – Oro verde, social change, and environmental destruction

In Tancitaro, Michoacán, the main road connecting two of the towns in the municipality winds through undulating countryside, flanked on both sides by avocado orchards. As we drive, Don Gerardo gestures out of the open window to the avocado trees:1

“All of this here – on both sides – it used to be fields of marijuana, just here right out in the open. They say that it was the Army who brought it here and said it should be planted, but who knows, right? Up until thirty years ago more or less it was like this, but now you see everything here is avocado. It’s a real problem because they’ve even cut down all of the pines as well”.

In recent years there has been a pronounced boom in demand for avocados in places such as the USA and western Europe. The health properties of this ‘superfood’, as well as its aesthetic qualities, make it primer fodder as Instagram content and as the inspiration behind a broad range of products. Its growing presence has sparked global media interest in where the fruit comes from, and the conditions on the ground in growing areas.

The focus on the issue of ‘cartels’ and their victimization of avocado producers is important, but it does not tell the whole story.

It misses the complex and historical web of relations of the agro-export industry more broadly.

This coverage has often focused on Michoacán, Mexico, not simply because it is the predominant growing area in the world’s biggest avocado producing country, but also due to the fact that it combines the coverage of fashionable avocados with the seemingly insatiable appetite for coverage of Mexico’s drug cartels and all things ‘narco’ related.

Much of the reporting has seemingly focused on attempting to educate – or indeed induce guilt from the reader eating their avocado toast – as to the conditions in which avocados are produced. The focus on the issue of ‘cartels’ and their victimization of avocado producers is obviously important, but it does not tell the whole story. Such reporting often reproduces simplistic state vs cartel narratives and misses the complex and historical web of relations of the agro-export industry more broadly.

The rise of the avocado industry in Michoacán is the product of broader processes of transformation in rural Mexico and indeed of the state in recent decades. To understand the complexity of the historical processes at play, and the relationships that they engender, a local level approach which goes beyond simple narratives of cartel activities to look at the broader impacts of social, economic, and environmental change that the growth of the avocado industry has produced – and the relationships of unequal power therein – is necessary.

The development of the avocado industry in Michoacán

Michoacán accounts for 80% of Mexico’s avocado production – which itself is the largest avocado producer and exporter in the world, with an average annual production of 1.56m tons over the last decade.2

Within Michoacán, 35 municipalities have certification to export avocados to the USA, but the key production area is concentrated within 11 municipalities which are located on the western and southern fringe of the Meseta Purepecha (the Purepechan Plateau – named after the indigenous Purepecha people who are originally from, and inhabit this area) as it descends towards the Tierra Caliente (hotlands) region. The scale of such cultivation has led to this area being referred to as the ‘Avocado zone’.

Whilst the criollo avocado is native to Michoacán, the widespread commercial cultivation of avocados in the state really began in the 1970s on the initiative of a group of businessmen in the Uruapan area – with the support of state institutions and private investment – who trialled the Haas avocado to see whether the region’s climate was amenable to such cultivation.3 The combination of temperature, precipitation, and volcanic earth, provided perfect avocado growing conditions and cultivation gradually started to spread.

The Haas avocado has a key advantage over the criollo in terms of commercialization as its thicker skin allows for refrigeration and gives greater protection from bruising, both of which makes it more suitable for transportation over long distances for both domestic consumption and particularly exportation. The growth in avocado cultivation continued during the 1980s and the early 1990s, and especially following the entry into force of the NAFTA agreement in 1994, which saw avocados from Michoacán exported to the US starting in 1997 – previously such exports had been banned for phytosanitary reasons. The ability to export to the US opened up the rapid expansion of cultivation and underpins the growth in the industry, especially from the mid-2000s onwards.

Licit and illicit cultivation in times of structural reforms

The growth of avocado cultivation has had a profound impact on crop cultivation – both licit and illicit – in what has become the avocado zone.

Traditional licit cultivations consisted of both subsistence and cash crops, such as corn, beans, wheat, sugar cane, and coffee. Given the wooded nature of large parts of the zone, a key economic activity in these municipalities derived from the pine and mixed forests therein, such as the sale of timber, woodwork, and resin tapping. Illicit crops, primarily marihuana, but also some poppy, have been cultivated historically in parts of the zone since the 1950s.

The growth of illicit crops in Michoacán was especially pronounced from the mid-1980s onwards as a result of the wider crisis in the Mexican countryside occasioned by neoliberal structural reforms.4 Specifically, whilst the Mexican state had played a role in supporting the prices of subsistence crops and also subsidizing agricultural inputs and services – such as through agricultural credit unions and the agricultural insurance system – this reduced significantly during the latter half of the 1980s and into the 1990s.5 This reflected not only the economic crisis brought about by the collapse in oil prices – which also raised the prices of some agricultural inputs as the peso devalued – but also a broader move away from domestic self-sufficiency in staples, towards an agro-export model.

This was underlined in the early 1990s with reforms to land ownership which opened up participation in agricultural production to small private companies to the disadvantage of existing agricultural associations (such as ejidos – community owned landholding associations).6 In the case of avocados in Michoacán, production had increased during the 1980s as the move towards an agro-export model gathered pace. However, as the US market remained closed, and the purchasing power of many Mexican families fell during the 1980s and 1990s, the increased production resulted in real price falls of nearly 60% from 1982 to 1991.7 Therefore, rural areas suffered a perfect storm as traditional agricultural production became unsustainable whilst the new model of agro-export was not ready to take its place.

As avocado prices rose over time, they also eclipsed illicit cultivations such as marihuana and poppy.

These were also replaced by avocado cultivations.

This was exacerbated in many respects by the advent of NAFTA which saw a reduction in prices for many crops, and a further turn to illicit crops (which were still rentable), as well as increased migration to the USA. However, NAFTA also signalled an opportunity for areas suitable for avocado production as the gradual opening of US states to exportation – and the fruit’s growing popularity in the US – meant that avocado cultivation became increasingly lucrative. This led to the further replacement of existing subsistence and cash crops with avocados in areas suitable for such cultivation. As avocado prices rose over time, they also eclipsed illicit cultivations such as marihuana and poppy and these were also replaced by avocado cultivations.

Forested areas were similarly cleared – either by felling or burning – to make way for avocado cultivation, even though this was illegal given the need for authorisation for changes in land use. Estimates vary but it is thought that around 50% of avocado cultivation in Michoacán is illegal as the change in land use has never been officially approved.8The changes in legislation around land ownership – referred to previously – also facilitated the parcelling up and sale of communally owned lands. Such land was often bought by entrepreneurs and already existing large producers who had the resources to invest in its cultivation, meaning that the former landholders became peones (agricultural day labourers) on their ancestral lands. Once the lucrativeness of avocado cultivation became clear, it provided further impetus to the clearance of virgin forest for such cultivation on the part of those who had previously sold their lands relatively cheaply.

The mass cultivation of avocados was seen to have an important impact on communities in the zone, for example:9

“Well, it was like a small town, very tranquil, not civilised. But because of the avocado boom… everything grew, everything”, and “…from the point at which the avocado started to be more valuable everything got very expensive here, very expensive. So, the land, the rent for houses; everything, everything is expensive, everything is more expensive here”.

Tensions have also been generated within local societies due to such a seismic shift:10

“Many people think that if you don’t have a huerta (avocado orchard) you don’t count for anything…I say this to you because they have said this a lot, personally to my family”.

Over time, the fact that such wealth has not led to a broader development of municipalities has also produced dissatisfaction and resentment amongst residents, as Margarita recalled: “The people prefer to buy in other places, invest in other places, so that complicates things massively”. Another interview with Antonio presents the same argument:11

“I tell you that little by little you started to see more money, you could see it in the houses, in the cars, you saw it from people’s clothes, in the trips they took, in the parties, in the weddings. In all that is the social area there started to be a change, but also a disparity because he who had a lot of money, well yes, started to have more money; but he who was an employee, kept on earning the same and so there was this inequality”.

Therefore, the wealth associated with avocado cultivation produced major changes within the societies of the zone, and indeed provoked social differentiation and divisions between those who had benefitted from such changes and those who did not.

The environmental and economic impacts of avocado cultivation

In economic, social, and environmental terms the impact of avocado cultivation has been seismic in Michoacán. Economic gains have been huge but highly unequally shared leading to transformed communities replete with social tensions as the majority remain mired in poverty as wages remain stagnant whilst costs rise. Similarly, the environmental consequences are becoming increasingly obvious as the remaining forests succumb to plagues, water runs short, and people suffer health complications.

Whilst organised crime may represent one actor with interests in such expansion, in reality there are multiple interests – state and non-state, licit and illicit – aiming to benefit from the economic riches stemming from avocado cultivation and export. And though tackling illegal orchards is seen as important in communities in order to reverse the loss of forests, there is very little appetite – aside from the odd headline grabbing statement – on the part of state agencies to tackle the problem. This is due to the fact that the industry produces important revenues – licit and illicit – for state actors (amongst others), and forms an important potential source of political revenues.

Aside from deforestation, the expansion of cultivations has caused significant environmental concerns given their impact on biodiversity and the environment. The phytosanitary requirements – dictated by the USDA (US Department of Agriculture) – which are necessary for exportation certification essentially dictate that no other crops, plants, or trees can be inside the export certified huertas aside from the avocado trees. This requires regular attention and the liberal use of pesticides to meet such standards and has had important ramifications in terms of a loss of biodiversity such as in plants, crops, and wildlife in the avocado zone. It also demonstrates the power that the USDA has over the way in which avocado is cultivated.

The lack of other plants within such huertas has also been seen as having led to increased surface run-off which has resulted in flash flooding when there have been heavy rains. The use of pesticides has affected the health of people in the avocado zone in the form of higher rates of cancer, respiratory problems, and the use of fertiliser – which provokes clouds of flies – causes gastrointestinal problems for many residents.

Given that the avocado zone is located on the fringes of a mountainous plateau, the cultivation of avocados has had a key influence on the water basin of the surrounding lowlands. Avocados utilise a significant amount of water, and far more than the equivalent area of pine trees for example. The huge growth in avocado cultivation has thus drained aquifers and has led to water shortages for crop cultivations within the southern Tierra Caliente region. The cultivation of avocados has also exacerbated the drying out and warming of the climate within the avocado zone which has seen temperature rises, and has meant that the production of avocados in some of the lower parts of the zone has become uneconomical.

This has increased deforestation as huertas are sought at increasingly high altitudes where the temperature is still cool enough for avocado cultivation. The warming of the climate and use of pesticides have also provoked plagues which have affected the native pines trees, causing them to dry out and die. Thus, residents of the zone – whilst acknowledging the positive impact that avocado production has brought in terms of jobs and economic benefits – also speak of the ecocide which has been visited upon their local environments.

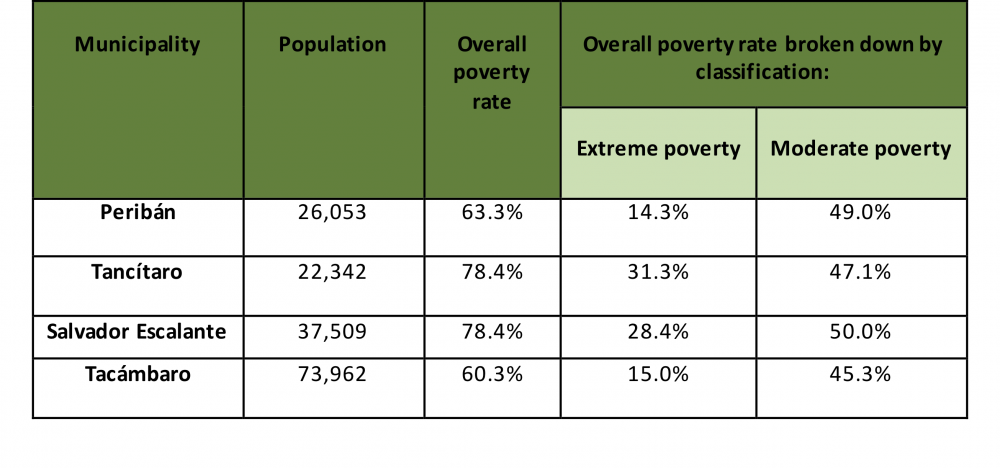

Whilst avocado production has reduced poverty and migration levels within the key producing municipalities, such reductions have been marginal. For example, in the latest census – conducted in 2010 – some of the major avocado growing municipalities had the following rates of poverty.12

This reflects the fact that the riches stemming from the trade are shared unequally amongst those who form part of the supply chain. The agricultural day labourers who cut the fruit, and those who live within the huertas to attend to the daily needs, earn wages that are generally speaking slightly higher than what an agricultural labourer in the neighbouring Tierra Caliente would earn. A person cutting avocados from the trees – which is extremely arduous work, especially if the terrain is not flat – can earn around $250 pesos a day, which is roughly USD $12 in 2020 prices.13 Such earnings are minuscule when compared to the riches concentrated elsewhere in the supply chain. Producers who own the land on which the avocados are cultivated gain far more from the trade, but how much depends on the amount of land that they cultivate, the maturity of the trees, and whether they produce for domestic or the more lucrative export market.

It is said to be possible for a family to live well on the proceeds from 0.5 to 1 hectare of cultivated avocado, and producers with 5 hectares or less are seen as small producers. In Tancítaro, for example it is estimated that 70% of avocado growers are small producers, and thus, broadly speaking, earn a comfortable living from the trade – depending on the price they can obtain from export companies/intermediaries – but not spectacular wealth. The largest producers however, can have hundreds if not thousands of hectares of cultivated avocados and so the concentration of riches, and power, from avocado cultivation and commercialisation is really concentrated amongst the large producers, and particularly the packing and exportation companies (mainly foreign owned transnational corporations), though there is sometimes overlap (i.e. some large producers also pack and export on their own account).

Conclusion

This article shows that avocado can be considered to be ‘oro verde’ but only for relatively few. As one interviewee put it:14

“The mode of producing avocados here is generating important environmental damages and enriching very few. And many continue mired in poverty, so despite the fact that much of the area is dedicated to avocados it isn’t everyone’s, this cultivated area. So I think from this the inequality gap is important and I think the environmental impact is also significant”.

In Michoacán, the economic, social, and environmental impact of avocado cultivation has been staggering. Economic gains have been huge but highly unequally shared leading to transformed communities replete with social tensions as the majority remain mired in poverty as wages remain stagnant whilst costs rise. Similarly, the environmental consequences are becoming increasingly obvious as the remaining forests succumb to plagues, water runs short, and people suffer health complications.

Citizen efforts to stop deforestation and reforest areas with native pines were gathering pace during my last visit to the avocado growing region in 2019, and these have continued subsequently as the growing impact of climate change becomes more prevalent. Despite participation in such movements some residents nonetheless look at the avocado orchards and the pines succumbing to plagues and feel that it may be too late for their municipalities in terms of preventing environmental collapse. As such, some hope that their experiences will serve as a cautionary tale to others to avoid a similar fate. Though given continued rates of deforestation – often through deliberate fires – across south central Mexico, one which does not appear to be being heeded.

Finally, as the avocado example demonstrates, both state and non-state interests are served by such an industry, which can have ties to drug trafficking and cartels, but the violence involved – both physical and structural – is not only utilised by criminal groups. And given the overwhelming rate of impunity in Mexico there is little disincentive to use violent means to achieve such ends. As with the broader panorama of contemporary Mexico, understanding such processes through a lens of state versus cartels can at best give a partial picture, and indeed often obscures the way in which the interests of state actors coincide with those of illegal actors.

Notes

- Field diary 2019. All names within this article are pseudonyms to protect the identities of interviewees. ↩︎

- Federal Ministry of Agriculture, 2019. ↩︎

- Martín Carbajal, M. D. L. L. (2016) ‘La formación histórica del sistema de innovación de la industria del aguacate en Michoacán’, Tzintzun. Revista de estudios históricos, (63), pp. 268-304. ↩︎

- Maldonado Aranda, S. (2012), “Drogas, violencia y militarización en el México rural: El caso de Michoacán”, Revista mexicana de sociología, vol. 74, núm. 1, pp. 5-39. ↩︎

- Hewitt de Alcántara, C. (1994) ‘Introduction: Economic Restructuring and Rural Subsistence in Mexico’, in Hewitt de Alcántara, C. (Ed.) Economic restructuring and rural subsistence in Mexico: corn and the crisis of the 1980s (University of California, San Diego) pp. 1-24. ↩︎

- Martín Carbajal, M. D. L. L. (2016) ‘La formación histórica del sistema de innovación de la industria del aguacate en Michoacán’, Tzintzun. Revista de estudios históricos, (63), pp. 268-304. ↩︎

- Colín, S. S., Oviedo, P. M., López-López, L., & Barrientos-Priego, A. F. (1998) ‘Historia del Aguacate en México’. ↩︎

- Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable y la Soberanía Alimentaria (CEDRESSA) (2017), ‘Caso de Exportación: Aguacate’. ↩︎

- Interview with Maria, 2017. ↩︎

- Interview with Margarita, 2017. ↩︎

- Interview with Antonio, 2017. ↩︎

- Overall, Michoacán is the 5th poorest state in Mexico with a poverty rate of 55.3% (2016 – 45.9% in relative poverty, 9.4% in extreme poverty (CONEVAL 2016). ↩︎

- This varies depending on the person however, as cutters are paid ‘bit rate’ – i.e. they are remunerated according to how much fruit they can cut (as is the case in much of US agricultural production as well). One unintended consequence of this is that some cutters become addicted to drugs – methamphetamine principally – which they take in order to be able to overcome physical pain and stress to continue to cut fruit. ↩︎

- Interview with Francisco, 2017. ↩︎