The Violence takes place series is edited by Jayson Maurice Porter, and co-edited by Alexander Aviña.

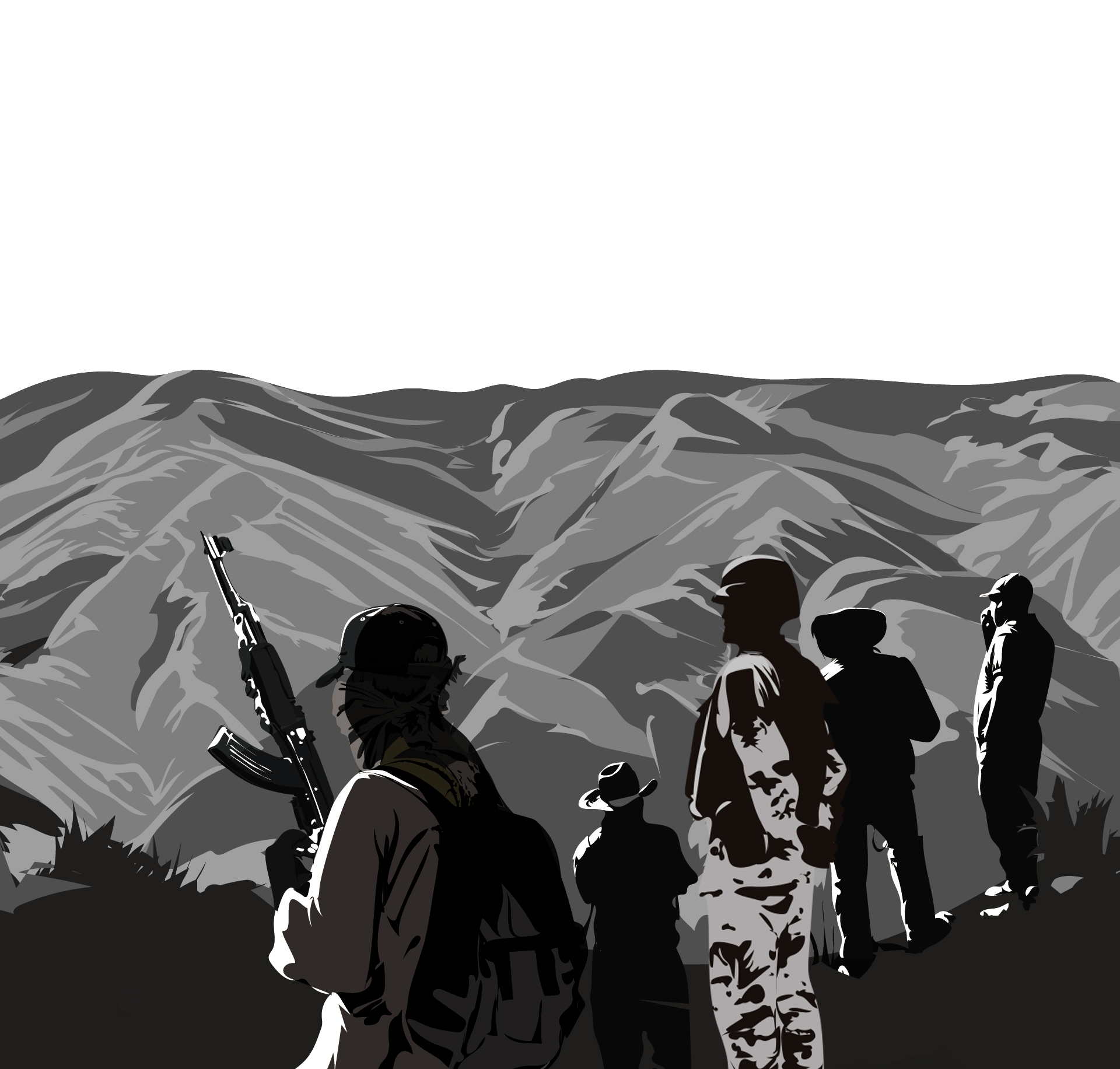

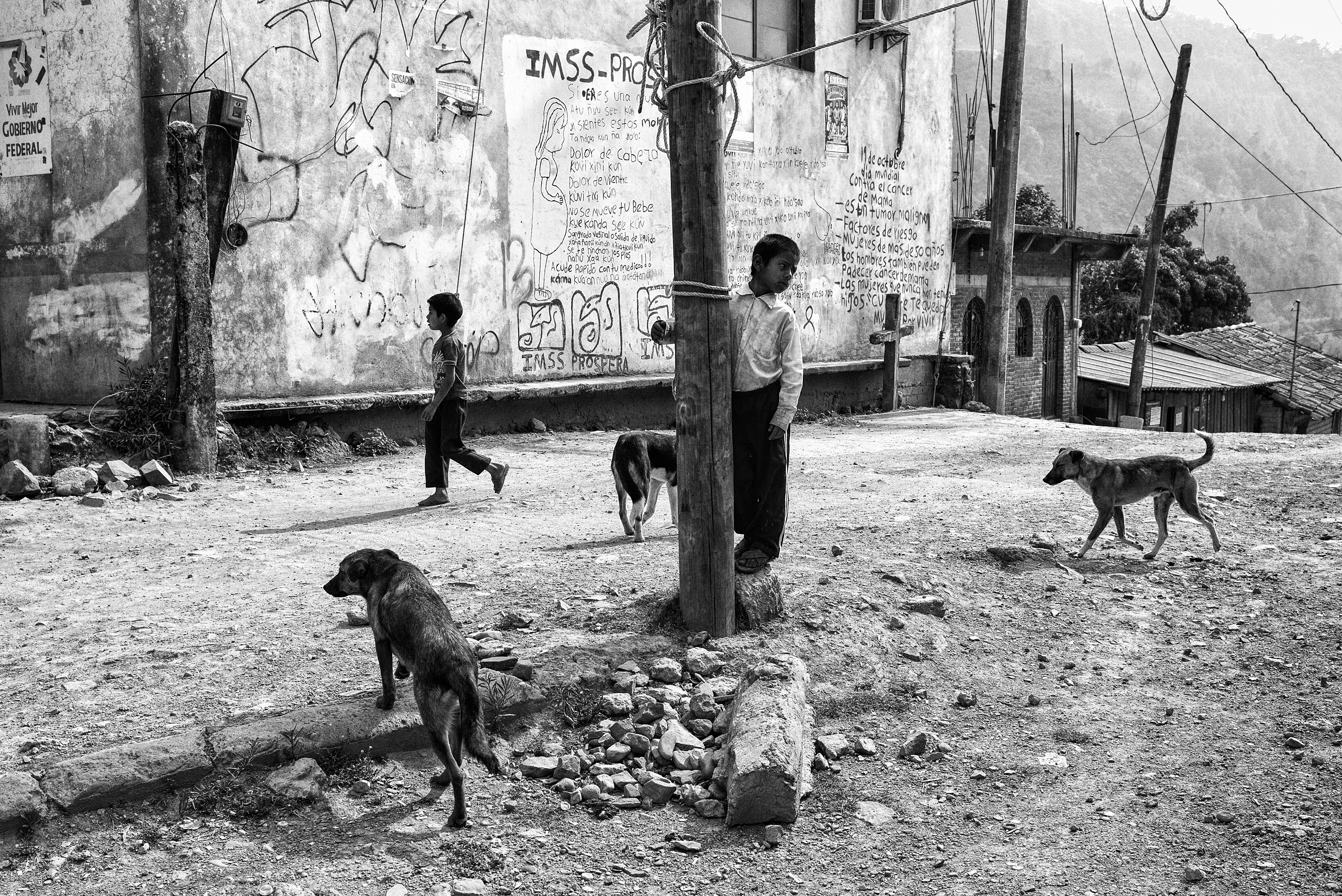

This series on violence in the Mexican countryside foregrounds local histories of the past and present. These insights help show how rural violence takes place in Mexico; how they are often overshadowed, underemphasized, or ignored entirely. In this perspective, local history and ecology are necessary for studying violence against and between the poor.

Far from the dominant, overarching narco-narratives, violence must be geographically and socially situated. This is why our analyses are based on grounded, local and empirical perspectives of rural Mexico.

Our work will analyze the relation between drug trafficking, violence and rural life in Mexico. As we will show throughout the different contributions, the distinction between licit and illicit crops is porous, just as the association of violence with drug trafficking is not always obvious. For the most part of the 20th century, in rural areas of Michoacán, Nayarit, Guerrero and Sinaloa, everyday conflicts in ranchos and villages often resulted in tragic outcomes. Such conflicts may be related to illegal activities, but they were also about land disputes, clashes between various factions, or vendettas seeking to right “honor offenses.”

In this respect, violence could be linked to drug trafficking, but it is not the only explanation or reason for it. Following that line of thought, the following series of studies aims to contribute to the debate over violence, rural areas and drug trafficking. We know that over the last years, Mexico has been affected by a terrible security crisis ; but we do not know much about the distribution of violence and its local manifestations.

In order to change this state of affairs, this series relies on ethnographical and historical work that shows that in various rural areas of Mexico the rupture between a supposedly “governable” country and one plagued with criminal violence does not make sense.

History and ethnography are key tools to further the debate, which, at present, seems to be dominated by analyses arguing that the causes for violence are easy to identify. We are highly skeptical of any analysis according to which violence can be understood by pointing to its results – characteristically, the control of a plaza or a drug route – that people can obtain solely by resorting to coercion. Such analyses forget that violence is part of social processes, with a defined timeframe. They dismiss the fact that the motives for acts of violence do not necessarily determine their results, and determine even less the way they are interpreted. Similarly, even if we were to admit that violence is produced by rational individuals who pursue specific interests, we would have to add that said interests are defined by historical and cultural backgrounds that need accounting for.