This article is Chapter 2 of Noria MXAC “Violence Takes Place” Editorial Series.

Introduction

The first person to bring opium poppies to the Sierra of Nayarit was a teacher. At some point in the 1980s, he was posted to those mountains – the homeland of the Náayari people (known collectively as the Náayarite, or Coras) – and brought poppy seeds along with him from his previous job on the border with Sinaloa.

Teachers had been at the forefront of efforts to ‘modernise’ the Náayarite since the Mexican Revolution, and by the 1980s poppies had become an archetypal ‘modern’ cash crop in much of the country, and a key commodity within a roaring US-Mexican drug trade. Cultivating poppies and extracting their latex – the raw opium gum from which heroin can be refined – was, of course, illegal. But the teacher promised huge rewards to anyone who dared to partake in this new, illicit business, while other representatives of the state, including policemen, soldiers and local politicians, helped to protect the burgeoning local opium industry in exchange for a share in its profits.

Opium’s arrival in the Náayari homeland, like the military crackdowns and government programmes of previous eras, somewhat counterintuitively promoted the integration of the region and its inhabitants into Mexico’s economic, political and cultural mainstream. But the Náayarite have a long history of successfully resisting and, when necessary, accommodating outside influences in order to help them defend their autonomy. Opium production in the Sierra de Nayarit perfectly illustrates the dialectic between accommodation and resistance, “incorporation” and autonomy.

Opium has brought social and economic changes to Náayari communities, but it has also helped the Náayarite to maintain their traditional life-ways as small-scale farmers and ranchers in the Sierra – unlike their Spanish-speaking, mestizo counterparts in Nayarit’s altiplano and coastal lowlands, where intensive commercial agriculture now dominates. Opium profits have enabled young Náayari men to buy automatic rifles, drink too much beer, engage in bloody feuds with one another, and embroiled them in conflicts with both state forces and criminal organisations. But at the same time, this money has supported the continued practice of costumbre – an interlocking complex made up of descent-group and communal-level rituals, Church-based festivals, and faith in the power of saints, ancestors and pre-Hispanic gods, which remains central to local ethnic and socio-political identity.

Opium production in the Sierra de Nayarit perfectly illustrates the dialectic between accommodation and resistance, “incorporation” and autonomy.

Exploring how opium cultivation has affected the Náayarite – as individuals, families, members of communities, and as a people – can therefore help us understand how radical ‘modernisation’ efforts can end up supporting ‘traditional’ practices; how the presence – rather than absence – of the state can contribute to rising violence and insecurity; and how the distinct ethnic, political and economic identities of thousands of Indigenous people may be influenced in multiple contradictory ways through their participation in a multi-billion dollar, transnational and inherently extractive industry like the modern heroin trade.

Corn and Costumbre in the Sierra de Nayarit

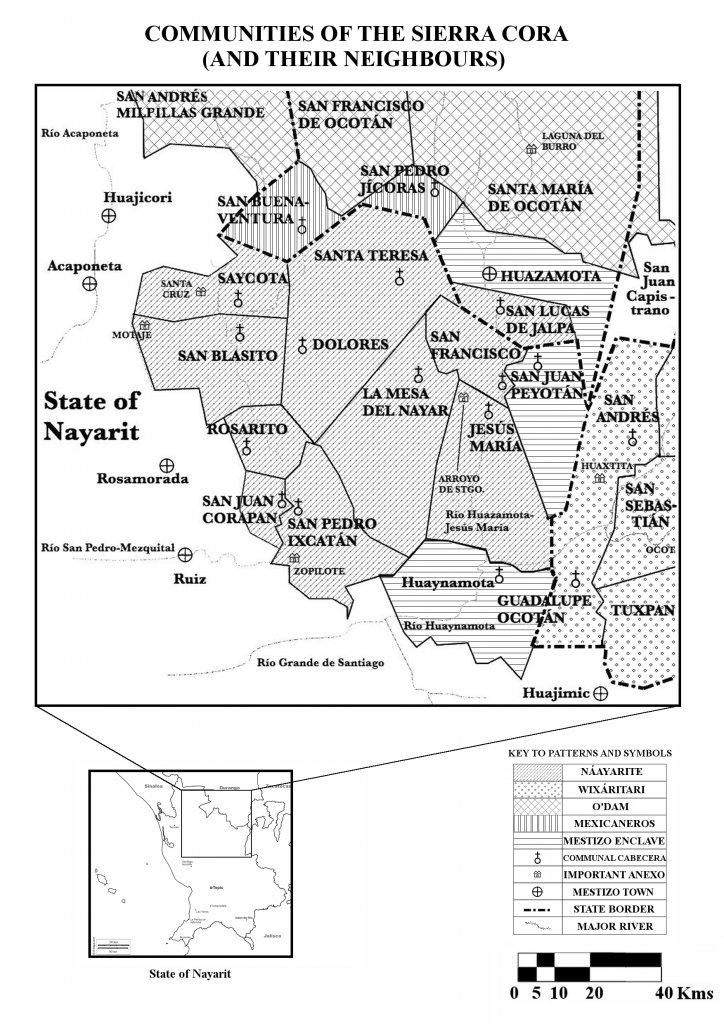

Almost all of the 28,718 speakers of the Náayari language registered in Mexico in 2015 live scattered across 5,000 square kilometres of Nayarit’s mountains and canyons. Their homeland covers eighteen percent of the state’s total area, and is its poorest and least densely populated region.1

The Náayarite have always survived by taking full advantage of the Sierra’s diverse ecological niches: rivers and seasonal streams full of fish and crustaceans, on the banks of which they plant crops and fruit trees; scrublands spreading up the sides of canyons that provide fertile soil, edible wild plants, and pasture for livestock; pine forests full of firewood, material for building houses, game animals, edible and medicinal plants and mushrooms, and more pasture.2 To get through the lean months of the dry season, the Náayarite have traditionally depended on stores of squash, beans, and maize, grown during the rainy season on small plots called coamiles. These are cleared using slash and burn techniques, tended mainly with machetes and coas (digging sticks), and shifted every few years.

Maize is the most important of these crops, and has been since the time of the Náayarite’s ancestors; since the time of the first men, in fact, whom the gods made not from clay or dust, but from maize dough. To the Náayari, maize is the sacred origin of all life, and alongside that grown for consumption, each Náayari clan sows its own special, ‘ancestral’ variety of maize, handed down from generation to generation for exclusive use in ceremonies known as mitotes. Celebrating these ensures, amongst other things, that the supernatural beings who control the universe will grant the participants health, protection, plentiful rains and a successful harvest. The ritual use of ‘family’ maize, and the initiation of children at mitotes that coincide with the harvest, emphasise familial and communal kinship bonds and the parallels between the life-cycles of humans and maize.3

Drugs, Development, and Náayari Political Economy

However, while the Náayarite believe that ‘maize is life,’ few of them are able, today, to survive from its cultivation alone.

In the early twentieth century, government ‘development’ programmes began, in a slow and piecemeal fashion, to try to incorporate the Sierra into Mexican ‘civilisation.’ This project involved the building of schools; corporatist, state-managed agrarian reform; violent anti-clerical crackdowns; and the local introduction of ‘improved’ agricultural techniques and small-scale industries such as logging and tanning. However, these programmes worked mainly to the advantage of mestizo settlers recently arrived in the Sierra, who quickly established links with regional mestizo military and civil authorities in order to usurp previously communal lands for planting, ranching and logging.

State policies that set out to transform not only the Sierra’s economy, but also dispersed Náayari settlement patterns and even the very landscape itself, therefore disrupted subsistence strategies that local people had developed over thousands of years in response to unique local conditions. By the middle of the twentieth century they had also increased the awareness of Nayari leaders as to the monetary value of their lands and resources, which previously formed part of a landscape defined by ritual, rather than its potential for profit.

Náayari and mestizo caciques (local bosses) alike gained much from state-promoted economic projects in the Sierra de Nayarit, and many grew rich from rearing cattle, selling off local lands and embezzling government subsidies (causing frequent and often violent conflicts in the process). In a case from 1972, a local mestizo cacique took control of a tractor that the federal government had donated to a Náayari community and “quickly ruined [it] by using it to run errands without changing the oil or filters.” When challenged by the community’s traditional authorities, his response was “to drink heavily and run around the town yelling, ‘the authorities have no right to judge crimes in this community.’”4 A house built with modern materials as part of a later government “development” program in the same community was similarly “appropriated by a man who had earlier been accused of systematically murdering his enemies in his position as the town’s police chief.”5

Meanwhile the vast majority of the Náayarite remained desperately poor, they became increasingly dependent on access to cash in order to buy food from new, government-run shops (which made up for a logging-induced decline in wild food sources); to invest in livestock; to finance religious celebrations; buy beer and tequila; purchase pick-up trucks and fuel; and partake of other fruits of global ‘modernisation,’ such as western medicine, mass-produced clothing, and breeze-blocks and aluminium roofing. The only option for many of those who wanted to earn cash was to migrate to the Pacific coast, to work as temporary labourers on commercial agricultural plantations during the dry season. There, entire families were housed together in cramped barracks with little in the way of ventilation or sanitation, working long hours outdoors in the tropical heat with few breaks, and spending most of the little money they earned on the overpriced food sold in the plantations’ own tiendas de raya (company stores).

Once poppies were introduced to the Náayarite in the 1980s, many saw in opium a convenient way of supplementing their traditional subsistence activities without having to leave their homes for months at a time to face the harsh conditions and low wages of the coast. The teachers who provided them with seeds used their long-standing positions as state-sponsored brokers of local cultural and political change to encourage poppy cultivation, explaining that the opium harvested from these flowers was far more valuable than any of the other cash crops – such as oats, alfalfa or peaches – with which some Náayarite had experimented in the past. “They all became good friends, and some started to sow little patches of poppy; before, the people here didn’t know about poppies, nor even marihuana. And I think that these are have hurt us. Now the young people, the kids, they don’t want to earn a hundred pesos, they want a hundred thousand pesos!”

In much the same manner as they cultivated maize, villagers sowed poppies in small plots carved from the local forests (which also hid them from prying eyes). They sold the opium back to the teachers, who then earned sizeable profits selling it on to regional drug-trafficking networks affiliated with Sinaloan capos. The traffickers took charge of processing the opium into heroin; most Náayarite remained peasants, rather than drug technicians, with little knowledge of the wider world of the drug trade.6 One Náayari acquaintance even explained that the bag of raw opium he showed me would eventually be turned into cocaine, so unconnected was he to the international heroin trade. Still, the rapid spread of this new, inherently commercial mode of agricultural production through the Sierra allowed local people to share in the profits of globalisation for the first time. “Soon, the planes started arriving, so many planes! One pilot was a big tall guy with a cuerno de chivo (AK-47) – back then no-one had seen one before, all they knew were .22 rifles, so they’d gather round him and admire it. He’d land the plane here, and get out a 24-pack of beers for all his friends here, and everyone would be drinking, all of us enjoying ourselves…”

“Now the youngsters are masters of the opium harvest”

Although for decades a numerous different state officials had protected and promoted opium production in the Sierra, in the early 1990s soldiers and police officers were sent to destroy local poppy plantations.

In order to protect themselves, their families and their crops, some Náayarite attacked their persecutors with hunting rifles, shotguns, or even AK-47 automatic rifles, purchased from corrupt officials or drug traffickers. Numerous local men – and a few soldiers, too – were killed in the resultant clashes, and many more were arrested and imprisoned. Some of those sent off to federal prisons in Tepic, Guadalajara or the Islas Marías prison colony off the Nayarit coast came into close contact with higher-level members of drug cartels. Some of these men – mainly mestizos from Nayarit, Sinaloa, Jalisco and even Michoacán – later came to the Sierra to visit their Náayari friends, helping some of them to expand their poppy-growing operations or transform themselves into local acaparadores (literally “hoarders”), responsible for bulk-buying opium and selling it on to full-time traffickers.

Despite the increasing risks of imprisonment or even death that those involved in opium production faced, the signing of NAFTA in 1994 pushed ever more Náayarite to depend on this illicit activity for their incomes. NAFTA cut into state subsidies for peasant agriculturalists and indigenous communities, flooded Mexican markets with cheap imports of US-grown maize, and undermined indigenous land-rights previously enshrined in the 1917 Constitution,7 which together led to the disintegration of the regional and national agricultural economies across Mexico, and left opium one of the few cash crops that could still earn highland peasants any money at all.

The sale of opium has enabled to resist the migratory pressures faced by indigenous peasants in much of the rest of rural Mexico, and to continue financing the ceremonies around which communal political and religious life revolves.

“Now the youngsters are masters of the opium harvest”, says the old man who first told me the story of how poppies arrived in the Sierra de Nayarit: ‘The youth today are masters of harvesting opium.’ In some communities, opium production has even become bound up with young people’s ethnic identities: a case of ‘I grow poppies, therefore I am Náayari.’ Moreover, the sale of opium has enabled them to resist the migratory pressures faced by indigenous peasants in much of the rest of rural Mexico, and to continue financing the ceremonies around which communal political and religious life revolves, helping many young Náayari to withstand the acculturative forces emanating from mainstream Mexican society. At the same time, their indigeneity has provided them with defensive mechanisms in the context of the Mexican government’s ‘War on Drugs.’ During various religious fiestas, participants mockingly dress up as soldiers, police officers, or notorious figures from the worlds of drug trafficking and politics, ritually referencing powerful external actors in ways that subvert their dominance and reaffirm the power of local identities and practices.

On a more practical level, Náayari poppy farmers use portable radios to warn each other about the movements and activities of state forces, communicating only in the Náayari language in order to render their messages incomprehensible to outsiders listening in. Other local people, particularly women, selectively claim ignorance of Spanish in order to avoid interrogation by soldiers or police officers.8 It is an ironic twist of fate, then, that the interventions of neoliberal elites pursuing a “war on drugs” alongside cultural, political and economic policies that constitute what is, in de facto terms, a “war on Indigenous identity,” have turned subsistence agriculturalists into much more “professional” drug producers, and transformed their indigeneity into a powerful defensive mechanism in the face of pervasive state violence.

Irrigated poppy cultivation has exacerbated inter-communal territorial conflicts, sometimes resulting in outbreaks of violence that echo the skirmishes of the revolutionary period.

However, the constant risk of losses due to government forces, hail storms, sudden frosts or plagues of insects, has encouraged many Náayarite to try to increase their yields by investing in small-scale irrigation infrastructure and commercial fertilizers and pesticides. Due to the practicalities of setting up gravity-fed irrigation systems, their poppy fields are increasingly set up next to streams; and given that the streams located in the most remote parts of each Náayari community often mark inter-communal boundaries, irrigated poppy cultivation has exacerbated inter-communal territorial conflicts, sometimes resulting in outbreaks of violence that echo the skirmishes of the revolutionary period.

The increasing use of fertilizers and pesticides has meanwhile eaten into local profits. This forces many Náayarite to spend ever more time supervising their poppy plots, obstructing their ability to simultaneously cultivate the maize that is so central both to Náayari ritual life and age-old subsistence strategies. And as merchants have tried to take advantage of the increasing monetization of the local economy by importing ever larger quantities of commercially-produced alcohol into the Sierra, social problems related to excessive drinking – namely chronic alcoholism, domestic abuse, and drunken, often lethal violence between heavily-armed young men, some of whose families have been feuding with each other since the 1940s – has climbed exponentially.

More recently, a precipitous drop in the price of opium in Mexico has forced the reduction of opium production in the Sierra, and increased the number of Náayarite leaving their homes in search of work in nearby cities or on the plantations of the Nayarit coast. Other locals, who as autonomous poppy cultivators had previously had little contact with drug cartels, have been directly contracted by the latter as labourers on poppy plantations in other parts of Mexico. Working for subsistence wages of 150 – 200 pesos per day, men, women and children, living in unsanitary conditions in temporary camps close to the poppy fields, risk illness and violent abuse. Taken far from their homeland, and integrated ever more tightly into the national drug economy, these labourers are becoming increasingly disconnected from the ritual practices upon which Náayari social and political life in is founded, which may in turn exacerbate local processes of social breakdown, and lead to a rise in interpersonal violence.

Conclusion

Thus poppy cultivation has, on the one hand, helped many Náayarite to hold on to their coveted political, cultural and territorial autonomy; but on the other, has increased the violence and other social problems affecting the Sierra de Nayarit, breaking apart families and even whole communities. The sudden, dramatic drop in the price of opium across Mexico has only exacerbated such problems.

What does the future hold? Perhaps the global crisis precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disrupted the cross-Pacific supply chains for synthetic heroin precursors, will lead to a new surge in demand for natural opium, putting cash back into Náayari pockets and helping to cushion them from ongoing physical, political and cultural threats. Or maybe the Náayari will go back to more traditional, subsistence-based lifestyles in the absence of alternative sources of income.

Only one thing is for sure: just as they have resisted the efforts of conquistadores, missionaries, revolutionaries, soldiers and cartel gunmen to dominate them over the last 500 years, so too will the Náayarite continue to fight for their right to control their homeland, their costumbre and their ethnic and cultural identities, no matter the odds stacked against them.

Notes

- CONAPO, Indices de marginacion 2010, last accessed 14 August 2014 ↩︎

- George Otis, ‘Clasificacion y aprovechamiento del paisaje entre los coras,’ Flechadores de estrellas: Nuevas aportaciones a la etnología de coras y huicholes (México: lNAH-Universidad de Guadalajara, 2003), p.135-40 ↩︎

- Philip Coyle, From Flowers to Ash: Náyari History, Politics, and Violence (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2001), pp.36-73 ↩︎

- Coyle, From Flowers to Ash, p.202 ↩︎

- Coyle, From Flowers to Ash, p.203 ↩︎

- For more information, see Romain Le Cour Grandmaison, Nathaniel Morris, Benjamin Smith, ‘The Last Harvest? From the US Fentanyl Boom to the Mexican Opium Crisis,’ Journal of Illicit Economies and Development (November 2019), Vol.1, No.3, pp.312–329 ↩︎

- See James B. Greenberg, Anne Browning-Aiken, William Alexander, and Thomas Weaver (eds.), Neoliberalism and Commodity Production in Mexico (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2012) ↩︎

- See Nathaniel Morris, ‘Serrano Communities and Subaltern Negotiation Strategies: the Local Politics of Opium Production in Mexico, 1940 to the Present,’ Social History of Drugs and Alcohol (May 2020), Vol.43, No.1 ↩︎