Election and Violence in Mexico

Project Launch Date : June 1st, 2021

On June 6th, 2021, Mexico organized its biggest elections ever. Figures are mind-blowing: 15 Governors positions, 30 entire local congress-seats, 1,063 Federal Congress-seats, and 1,926 Mayors positions will be up for competition in 30 Mexican states. In total, more than 21,000 officials will be elected in a single day.

Beyond the logistic challenge, another issue lies ahead for the Mexican democracy: the exploding violence that has been exerted against candidates and elected public officials over recent election periods. This is what this project will analyze.

Going Beyond the Narco Explanation

Between 2006 and 2009, the Mexican National Mayors Association (ANAC in Spanish) registered 158 assassinations of Mayors in the country. Moreover, the Justice in Mexico Program documented that 264 local politicians (Mayors, ex-Mayors, substitutes, and candidates) have been murdered since 2002. Of those, 98 have been killed between 2015 and 2019, the 2018 elections having been the most violent in history (145 murders).

Dozens of analyses have been published on this issue. They usually start with a series of questions: Who kills candidates? What are the motives? What impact does violence have on local and national political life? Yet, the answers and conclusions tend to follow a unique argument: the responsibility of violence is almost automatically attributed to “organized crime”. In the Mexican context: “el narco”.

Therefore, most studies explain electoral and political violence through a criminal incentive model. “Cartels” would exert lethal violence in order to control trafficking routes, or drug production sites; territories in order to extort public budgets and/or impose protection rackets on different legal and illegal activities; “capture” the State, its apparatus and personnel, in order to impose social and moral control on local inhabitants.

These arguments mainly rely on official sources (police reports) or news briefs (greatly influenced by the former), without properly putting them in perspective or into discussion. Therefore, they tend to feed the “narco” narrative that dominates political analysis in Mexico, and thus fail to fully understand the complexity attached to the dynamics of electoral and political violence in Mexico.

Our Questions and Objectives

-1- How did practices of electoral violence evolve in the recent years, and how can we better identify the actors behind them?

Electoral violence is neither a recent, nor unprecedented feature of Mexican politics. For example, between 1988 and 1992, thousands of opposition parties activists (the PRD, in this case) have been arrested, molested, tortured, assassinated and disappeared, in the hands of multiple politico-criminal groups). We will put our effort on identifying what has changed over the past decades, in order to identify trends, new practices, and modalities of electoral violence. We will be particularly attentive to the wide array of actors able to mobilize violence during electoral periods, as well as of the dynamics that may fuel such practices: local feuds (over land, property or family matters, for example); political parties’ conflicts, including internal ones; change of political affiliations; the role of businessmen; the role of “machine politics” at the state or federal level; the role of local strongmen (caciques) and other informal authorities; the role of armed public forces; and of course, the role of violent groups, including drug cartels and other criminal structures.

-2- How to better identify the causes of violence, and the actors behind it?

As said earlier, the states that are most affected by electoral violence are not necessarily the ones with the highest criminal presence, or the highest homicide rates. As it happens with other topics in Mexico, academic and media attention tends to follow spectacular events of violence and official homicides’ statistics, therefore creating a distorted vision what is happening in the country. Electoral violence has more to do with the way power is built and exerted, rather than with the mere presence of drug cartels (although Guerrero and Michoacán, as mentioned, which combine all the above mentioned dynamics, will be of crucial importance in order to study the connection between crime and electoral violence). Our project will respond to these questions by focusing on the local dynamics of coercion, without presuming of a simple explanation to them. This is where our methodology, based on extensive fieldwork, interviews and direct access to local actors (candidates, elected officials, the business community, members of armed and criminal groups) will be fundamental.

-3- Who are the most vulnerable populations, and where are they located?

We will follow a wide array of citizens that are affected by electoral violence: candidates, mayors, local public servants, local representatives, party leaders, activists, or journalists, among other “normal” citizens (the family of political candidates, for example). Although political campaigns and election periods represent peak moments of violence, we will aim at documenting electoral and political violence beyond these moments: what happens before the campaigns, and what happens after the elections, including for ex-mayors and ex-candidates, if of utmost importance. Then, it is crucial to give full space to inter-sectional characteristics of geography, age, social profile, gender, and ethnicity. For example, being an indigenous, female candidate in a rural area of Oaxaca is not the same as being a white male, avocado entrepreneur in the semi-urban region of Uruapan (Michoacán). Based on these axes, our project will cross and combine qualitative variables in order to identify and map the most vulnerable profiles of citizens.

-4- How to better measure electoral violence?

In Mexico, most studies take political parties’ affiliation as a crucial, infallible, and inalterable variable of analysis. Yet, history (and fieldwork) reveals constant bargains and strategies of power that play with parties’ etiquettes and nominations. This “political party shopping” is particularly strong at the municipal level, where it is very common for candidates to change affiliation according to different opportunities or constraints. In fact, in Oaxaca, Puebla, Guerrero and Michoacán, it is quite common to see a candidate going from PRI to PAN, PRD, or MORENA. Moreover, it is usual to observe the perpetuation of local dynasties where sons, nephews, wives or daughters assume an active political role after their fathers, even if it implies running for a different political party. In that sense, surnames might have much more political weight than a party affiliation. In such contexts, criminal and illicit interests, and the use of violence as a resource, are tied to parties’ dynamics in complex ways. Although there is no doubt about the rise of criminal groups’ political influence in the past years, it is crucial to better understand where, when, and why those political-criminal ties give room to lethal violence or not. Our work will therefore be of major importance in order to better understand the contemporary influence of illicit actors and political-criminal networks in elections, without following a binary “narcos vs. state” hypothesis.

-5- What kind of protection mechanisms exist for candidates in Mexico?

Electoral violence poses a direct threat to Mexican democracy: local elections cannot be a matter of “life or death” for local candidates. We will provide an exploration and evaluation of public policies of candidates’ protection that are in place in Mexico. We will also work with relevant Federal and state authorities in order to study these policies, and assess their efficiency, and will cross-check them with local actors’ testimonies and experiences. Electoral violence has more to do with the way power is built and exerted, rather than with the mere presence of drug cartels (although Guerrero and Michoacán, as mentioned, which combine all the above mentioned dynamics, will be of crucial importance in order to study the connection between crime and electoral violence). Our project will respond to these questions by focusing on the local dynamics of coercion, without presuming of a simple explanation to them. This is where our methodology, based on extensive fieldwork, interviews and direct access to local actors (candidates, elected officials, the business community, members of armed and criminal groups) will be fundamental.

Our Policy Reports

Policy Report n°1 – By María Teresa Martínez Trujillo and Sebastián Fajardo Turner

Data Analysis on Electoral and Political Violence 2020-2021. What the Data Shows, and What it Hides.

Policy Report n°2 – By Ana Velasco

If Elections are a Matter of Life and Death… How to Protect Electoral Candidates in Mexico?

Methodology and Added-Value :

Our Access to Local Actors, and Key Stake-Holders

Following Noria’s well established reputation and methodology, this project is based on a strong qualitative method, combining desk-work, fieldwork, interviews, observation, and documentation effort.

All our products shall be published in English and Spanish, in order to ensure a maximum impact.

The project offers an exceptional access to key local actors in order to better understand electoral violence in Mexico: political candidates and ex-political candidates; mayors and ex-mayors; a wide array of local important social and economic actors (businessmen, social activists or members of the church, for example); as well as violent and criminal actors, including drug-traffickers or members of Autodefensas militias.

These accesses lie on more than 10 years of experience in Mexico, including fieldwork and expert work in Michoacán or Guerrero.

Therefore, this project represents an unprecedented opportunity to document, from the ground, one of the most crucial challenges of violence, insecurity, and criminal dynamics in Mexico.

Project Team

Project Coordinator: Romain Le Cour Grandmaison

Project Officer: María Teresa Martínez Trujillo

Data Analyst and Researcher: Sebastián Fajardo Turner

Policy Analyst and Researcher: Ana Velasco Ugalde

Project Assistant: Alicia Landín Quirós

Translations and Copy Editing:

- Paul Kersey

- Ana Inés Fernández

- Isabel Alvarez-Echandi

Illustrations and Web-Design:

- Valentin Bigel

- Romain Lamy

Publications

-

Mexico & Central America

Violencia política: más allá de candidaturas y elecciones

-

Mexico & Central America

Political-Electoral Violence in Mexico, 2020-2021. What the Data Shows, and What it Hides.

-

Mexico & Central America

Data on Political & Electoral Violence in Mexico, 2020-2021

-

Mexico & Central America

Executive Summary – How to Protect Electoral Candidates in Mexico?

-

Mexico & Central America

How to Protect Electoral Candidates in Mexico?

-

Mexico & Central America

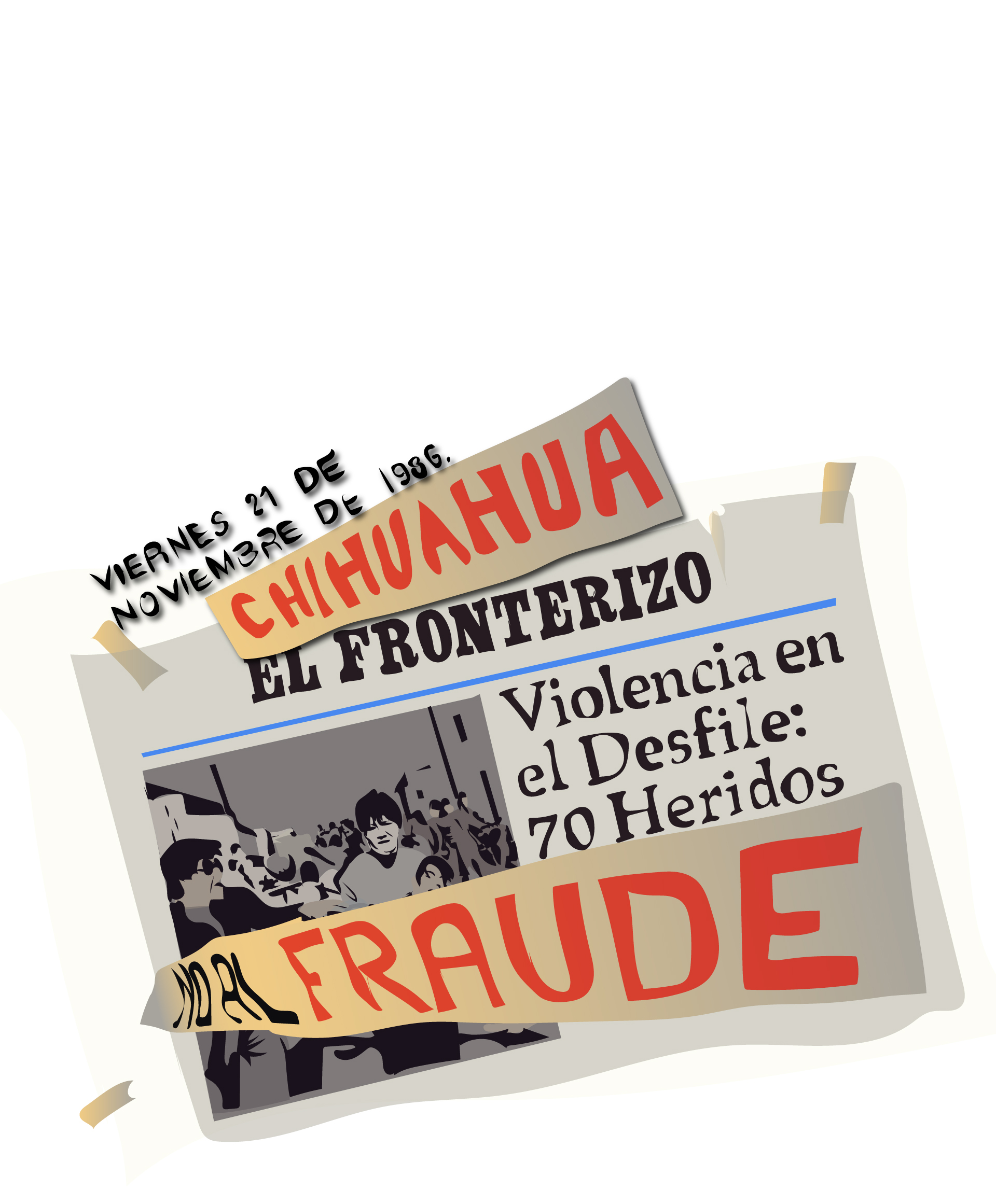

The Hard Work of Fraud. Winning Elections and Losing Legitimacy in Chihuahua

-

Mexico & Central America

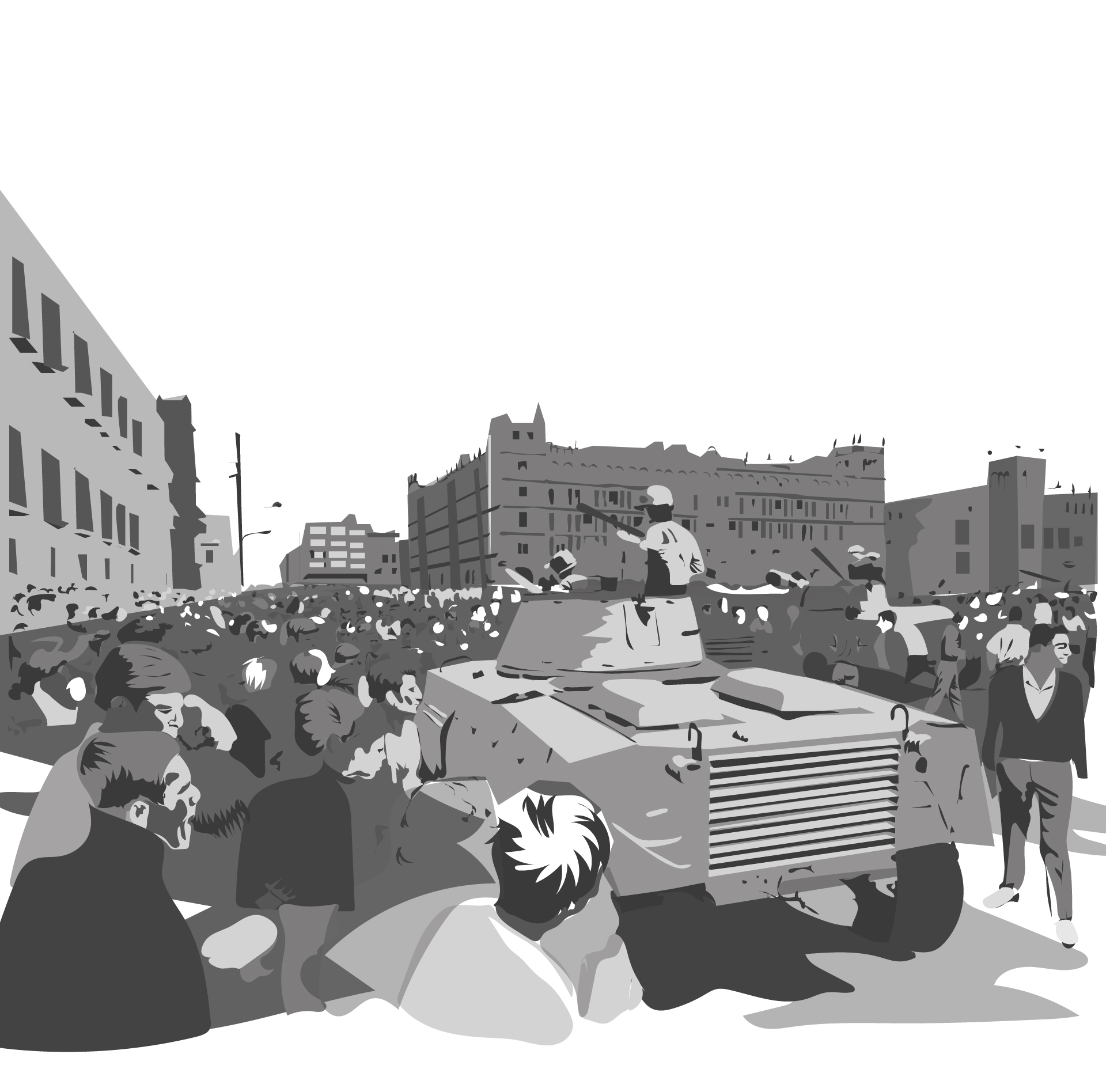

Killing Candidates in Mexico. The PRD in the 1990s.

-

Mexico & Central America

A Short History of Violence and Elections in Mexico