A decade has passed since the United Nations formally adopted the SDGs as a global call to action and since the World Bank announced its grand push for supporting climate resilience—an initiative it called “from billions to trillions”. Across much of the global south, these developments were received with measured optimism and hopes that a new era might at last be dawning. And yet, the intervening period has shown that to be anything but the case. Today, a majority of lower and lower-middle income countries face staggering and compounding challenges as they attempt to chart a better course for the future. Central to their troubles is the workings of the global financial system.

This paper will explain why global finance has come to play such a destructive role in much of the global south. Drawing net financial flows to the fore, we will show that rather deliver capital the places where it is sorely needed, the global financial system, through a variety of mechanisms and channels, has been extracting capital out from those places over the last ten years. Predictably, the results of this have proven destructive on social, ecological, and developmental levels. And unless the direction of these flows is shifted through a structural change in the political economy, things will only get worse in the years ahead.

Background

The economic problems currently facing southern countries have reached alarming levels. Half of all southern countries are headed towards, or are currently experiencing, debt distress.[1] This breadth has not been seen since the crisis days of the early 1980s. For many lower and lower-middle income countries in the Global South, attaining economic stability and financing while dealing with climate change in today’s political-economic backdrop is becoming increasingly difficult.

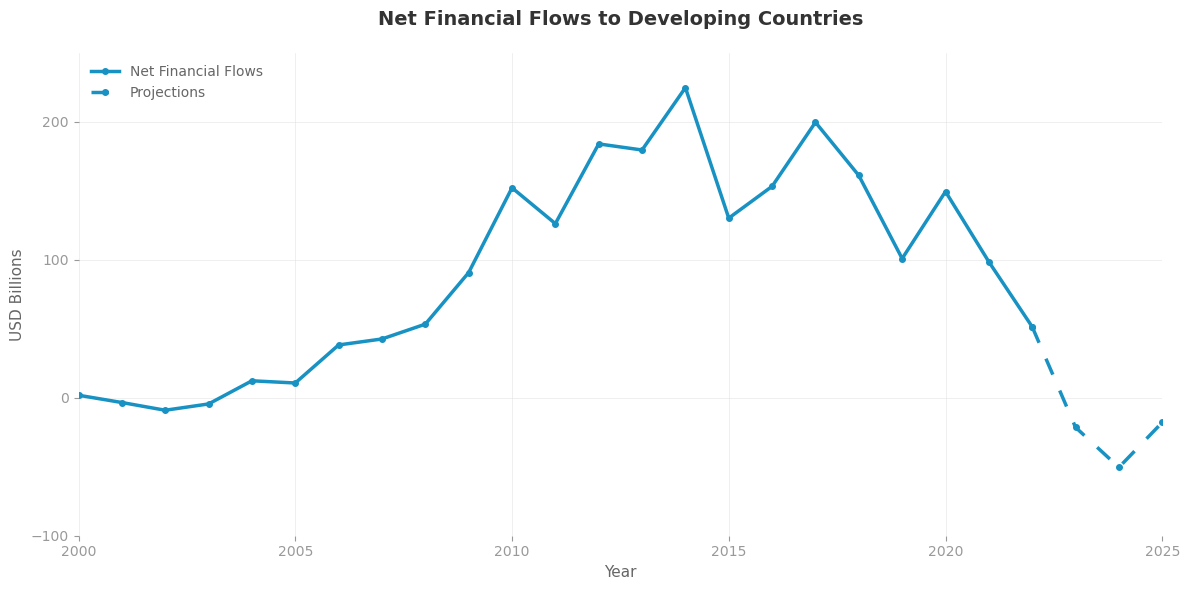

One of the major factors that places the developing world in economic distress is a dramatic turnaround in net financial flows, which have been negative for the last two years. After peaking in 2014, flows into developing countries commenced a downward trend, one that accelerating sharply since the COVID-19 pandemic. Projections show that net flows will either remain precariously low or turn negative again in 2025 for much of the developing world. Breaking it down by income group: middle-income countries are likely to remain in this state of negative net flows, lower-middle-income countries are teetering on the edge, while low-income countries are somewhat shielded from experiencing negative net flows due to their dependence on aid finance.[2]

Data Source: One Data

When countries face negative net financial flows, it means that the flow of money being sent to the developed world is more than what they are receiving in return. In other words, the developing world is subsidising profit to the rich world. This is occurring primarily due to the onerous debts accumulated in the global south. In recent years, these debts have expanded at a rapid pace.

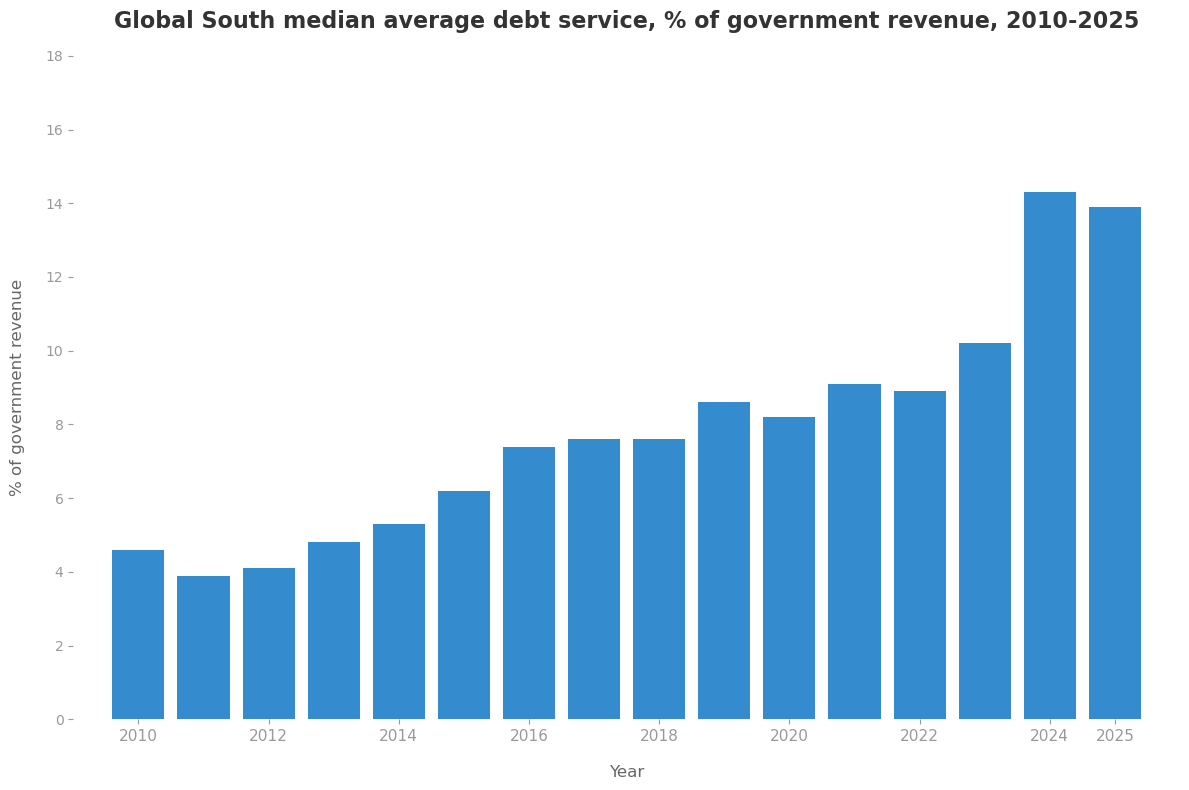

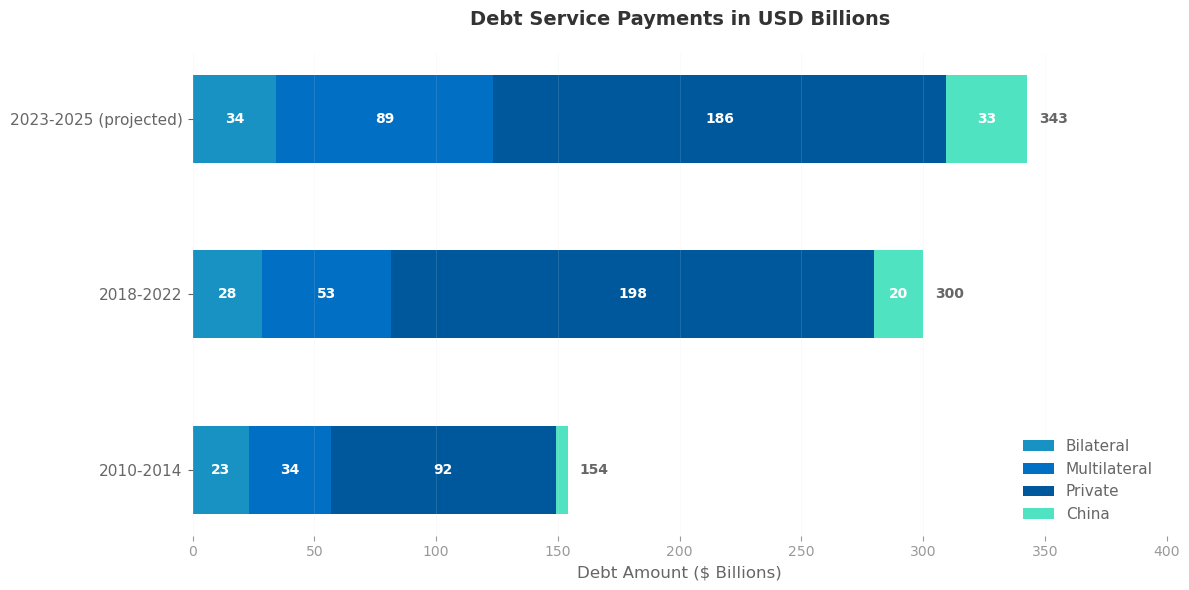

Importantly, the issue extends beyond just the sheer volume of debt—just as relevant have been rising costs associated with debt servicing. In 2023, southern countries paid a record $1.4 trillion in total debt service.[3] This included $400 billion in interest payments, a figure that tripled from a decade ago. In total, debt payments in the south are the highest level since the 1990s, with such expenditures on average absorbing an estimated 14% of government revenue in the current period.

Source: Debt Justice Calculations

Alarmingly, twenty-six countries saw net negative transfers in 2023, amounting to $48 billion.[4] For 2025, those making net negative transfers might jump as high as forty-four, while the volume of transfers will likely exceed $100 billion. Leading authorities also project that 2026 will be another peak year for debt payments.[5]

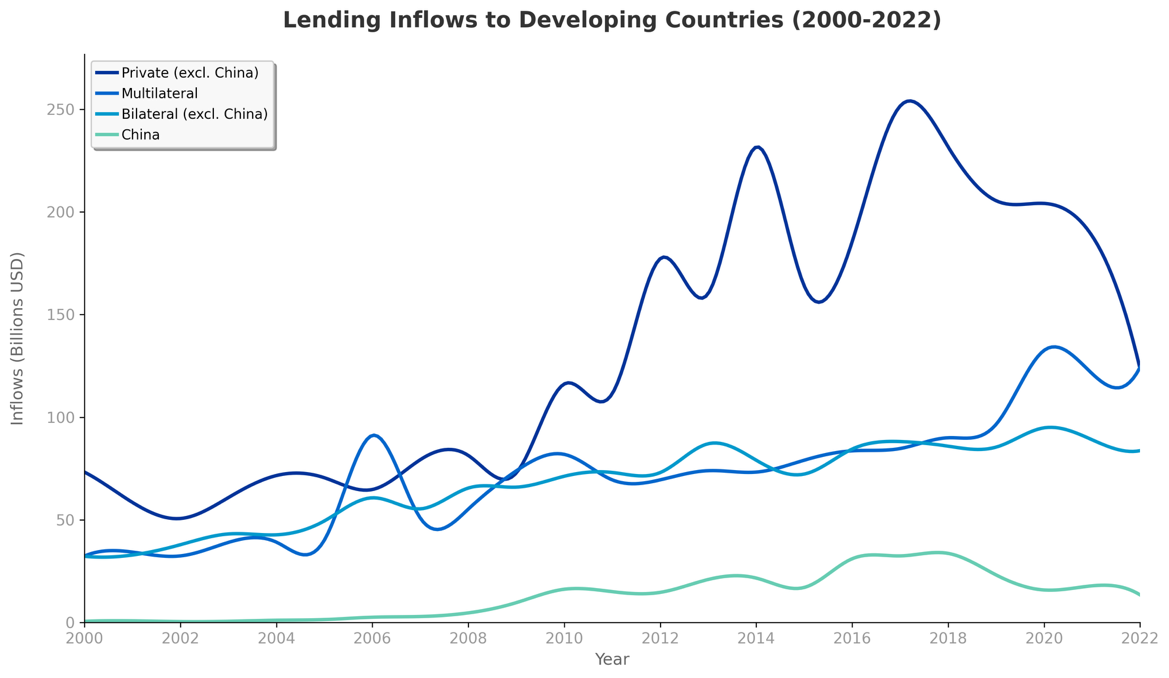

The Role of Private Capital Markets

To understand how these conditions came about, one need understand the volatility of private capital markets. Following the 2008 global financial crisis, loose monetary policies instituted at the Federal Reserve first and foremost provided investors in rich economies with cheap money.[6] Finding a lack of investible opportunities within their home economies, the surplus liquidity slushing around Wall Street and the City would lead to an uptick in private capital flows to the global south. With time, financiers moved further and further out the risk curve. In total, lending to the south increased nearly threefold between 2010 and 2018, peaking in 2017 at $252 billion.

Source: One Data

After 2017, however, the direction of financial flows reversed. Prompting the pivot was the Federal Reserve. As the Federal Reserve hiked rates from zero to over 2 per cent between 2015 and 2019, investors moved their capital out of southern countries, contributing to a drastic build-up in debt across the global south. And with the COVID-19 pandemic, the disinvestment trend became even more pronounced. Facing grave uncertainty, 2022 saw investors retreat en masse to safe haven assets such as US Treasuries. And things only got worse thereafter. Once the Federal Reserve hiked rates in 2022, pushing rates above 4.5 per cent, the yields available in core economies improved substantially. This gave even lesser reason to expose one’s capital to the economies of the global south.

Critically, just as credit flows to the south were drying up, payments on existing debt obligations were increasing. For a sense of scale, consider that for southern countries, debt service payments in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis were about $150 billion, whereas they are today more than $340 billion. Most of these payments accrue to private bondholders. These parties have received nearly two-thirds of total debt repayments since 2018. This is because interest rates on bonds held by private creditors are drastically higher interest rates than those of other creditors.

Source: IMF International Debt Statistics

The Failures of International Financial Institutions

When established at Bretton Woods, the primary mandate of the International Monetary Fund was to provide countercyclical financing to countries in crisis. The World Bank, meanwhile, was charged with providing concessionary development-oriented financing. In recent times, both institutions have failed to honor their missions.

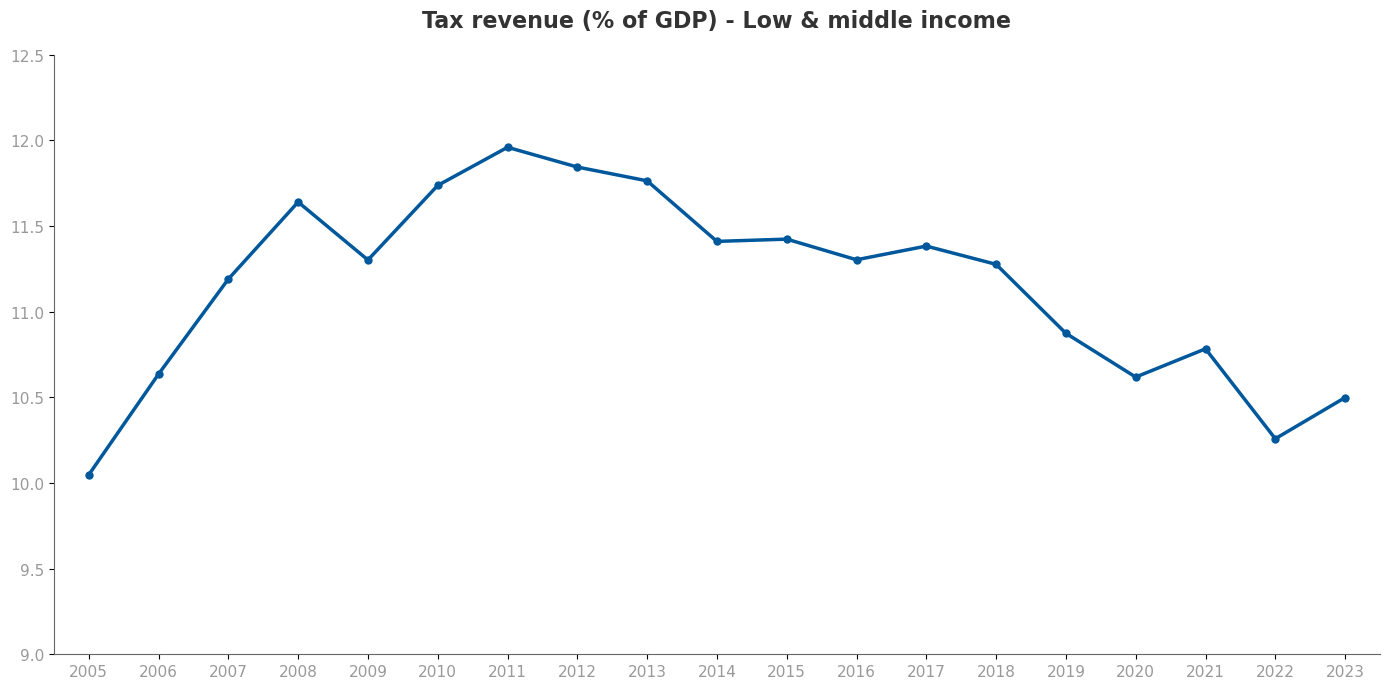

Between 2022 and 2023—a time when private capital was fleeing from the global south— net transfers from both the World Bank and the IMF dropped significantly, falling by $19 billion and $6 billion, respectively.[7] Surcharges attached to large or recurring loans by the IMF only made matters worse for many debtors in the global south. These years clarified what function these international financial institutions actually serve: Rather than support macrostability and growth, they enable the volatility and pro-cyclical movements of the US-led global financial system. The IMF’s record in chronic borrowers like Egypt and Argentina testifies as much. As enforcers of austerity and disciplinary providers of foreign exchange, these institutions also facilitate wealth outflows from the global south: In effect, they ensure private creditors are made whole and that the costs of doing so are shifted onto the citizenries of the global south.

Source: World Bank

Conclusions

The consequences of the financial turmoil just described are ominous. Most immediately, they threaten to create two decades of lost growth in the global south, an eventuality that will turn the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into a pipe dream. Indirectly, the workings of the global financial system are also imperiling green transitions. To protect themselves against volatility and unwanted interventions from the World Bank and IMF, a great many governments have been forced to focus on building up reserve assets. Implicitly, this decreases the amount of capital they are able to devote to national development, green energy and low-carbon infrastructure. In many instances, accumulating reserves requires intensifying austerity, too. According to an analysis by economists Isabel Ortiz and Matthew Cummins, 85% of the world population, more than six billion people, are currently living through a form of austerity measures.[8] Furthermore, 3.4 billion people presently live in countries that spend more on interest payments than health expenditures[9], and 2.1 billion live in countries where interest repayments surpass education spending.[10] These types of budgetary arrangements—where debt repayment is prioritised over human needs—are disproportionately observed in Africa today. As one prominent debt relief campaigner explains, “the 1982 crisis lasted over twenty years, with much suffering, before it was finally resolved in 2005. We do not have a generation to tackle this new debt crisis”.[11]

Indeed, much of the global south faces a bleak reality. Integrating into the global trade system necessitates integration into the global financial system. As the latter is dollar-based and vertically organized, the price of integration includes heightened vulnerability to short-term capital flows and cycles of boom-and-bust that are driven by the policies and needs of states in the global north.

Part and parcel of these issues are the politics of IMF quotas. The Fund distributes voting power based on an outdated model that favors countries from the Global North.[12] As these countries are the primary beneficiaries of the existing global financial system, they oppose any change to IMF policy which might alter how the global financial system works. But alterations are needed—and are very possible. Several reforms have been proposed: utilising unused Special Drawing Rights; updating the outdated IMF quotas system; removing IMF tiered interest rates and eliminating IMF surcharges; and lastly, debt cancellation.[13] Clearly, any reform must place climate and the needs of the population before debt service.

Cover Photo Credit: World Bank, “World Bank Headquarters 2013: World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings” (April 2013).

[1] United Nations Secretary-General, “Confronting the Debt Crisis: 11 Actions to Unlock Sustainable Financing” (United Nations, June 2025), https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Confronting-the-Debt-Crisis_11-Actions_Report.pdf.

[2] Sara Harcourt, Joseph Kraus, and Jorge Rivera, “Net Financing Flows to Developing Countries Remain Precariously Low,” One Data, April 18, 2025, https://data.one.org/analysis/net-financing-flows-remain-low.

[3] World Bank, International Debt Report 2024 (World Bank, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-2148-6.

[4] Sara Harcourt, Jorge Rivera, and David McNair, “Net Finance Flows to Developing Countries Turned Negative in 2023 – ONE Data & Analysis,” One Data, April 16, 2024, https://data.one.org/analysis/net-finance-flows-to-developing-countries.

[5] United Nations Secretary-General, “Confronting the Debt Crisis: 11 Actions to Unlock Sustainable Financing” (United Nations, June 2025), https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Confronting-the-Debt-Crisis_11-Actions_Report.pdf.

[6] Rodrigo Fernandez, Pablo Bortz, and Nicolas Zeolla, “The Politics of Quantitative Easing a Critical Assesment of the Harmful Impact of European Monetary Policy on Developing Countries,” 2018, https://assets.nationbuilder.com/eurodad/pages/496/attachments/original/1590605202/The_politics_of_quantitative_easing.pdf?1590605202.

[7] Charlotte Rivard and Homi Kharas, “Swimming against the Tide on Financing for Development,” Brookings, April 11, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/swimming-against-the-tide-on-financing-for-development/.

[8] Isabel Ortiz and Matthew Cummins, “END AUSTERITY: A Global Report on Budget Cuts and Harmful Social Reforms in 2022-25,” October 2022, https://pop-umbrella.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/0d4bcf52-376c-4b16-83cb-4e1489d5a52a_Austerity_Ortiz_Cummins_FINAL_26-09-2022.pdf.

[9] United Nations Secretary-General, “Confronting the Debt Crisis: 11 Actions to Unlock Sustainable Financing” (United Nations, June 2025), https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Confronting-the-Debt-Crisis_11-Actions_Report.pdf.

[10] “The Jubilee Report: A Blueprint for Tackling the Debt and Development Crises and Creating the Financial Foundations for a Sustainable People-Centered Global Economy” (Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, 2025), https://ipdcolumbia.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Jubilee-Report-7.17.pdf.

[11] Larry Elliott, “Developing Countries Face Worst Debt Crisis in History, Study Shows,” the Guardian (The Guardian, July 21, 2024), https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jul/21/developing-countries-face-worst-debt-crisis-in-history-study-shows.

[12] Maia Colodenco, Florencia Asef Horno, and Marina Zucker-Marques, “A Challenging Imperative: IMF Reform, the 17th Quota Review and Increasing Voice and Representation for Developing Countries” (Boston University Global Development Policy Center, April 2025), https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2025/04/GEGI-GCI-Quotas-Report-2025-FIN.pdf.

[13] Bretton Woods Project, “Reconceptualising Special Drawing Rights as a Tool for Development Finance,” Bretton Woods Project, October 2, 2023, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2023/10/reconceptualising-special-drawing-rights-as-a-tool-for-development-finance/; Bretton Woods Project, “IMF Quota Review: Putting Climate at the Core of IMF Governance Reform,” Bretton Woods Project, December 8, 2022, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2022/12/imf-quota-review-putting-climate-at-the-core-of-imf-governance-reform/; Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky, Francisco Cantamutto, and Laura Clérico, “IMF’s Surcharges as a Threat to the Right to Development,” Development, August 23, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-022-00340-5; Debt Justice, “Cancel the Debt: Why Lower Income Countries Are Demanding Debt Cancellation,” April 2023, https://debtjustice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Global-South-Briefing.pdf.