Fourteen years after the popular uprising of 2011, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has taken control of Syria’s state institutions. Amongst other things, President Ahmed al-Shara’a1 is presently tasked with reviving the economy and rebuilding a country burned by years of war. To achieve this, he has turned to a circle of technocrats and businessmen that closely resembles the team Bashar al-Assad once entrusted with liberalizing the economy. Linked to Western and Gulf business elites and drawn from networks that have long since promoted Syria’s integration within regional circuits of accumulation, al-Shara’a’s appointments suggest that the more things change, the more they can sometimes stay the same.

Years of sanctions and civil war have undoubtedly brought Syria’s economy to its knees. According to UN estimates, the cost of the country’s reconstruction exceeds US $400 billion and the national poverty rate has nearly tripled from 33 percent prior to the conflict to approximately 90 percent today2.

Against this backdrop, Ahmed al-Shara’a determined that normalizing relations with the international community and streamlining Syria’s reinsertion into the global financial system would be pillars of his economic policy. To carry out his agenda, as mentioned, he enlisted to familiar group of Syrian technocrats and businessmen. Abdelkader Husrieh was appointed Governor of the Central Bank of Syria. Muhammad Yisr Barnieh was brought into run the Ministry of Finance. Abdulsalam Haykal was named Minister of Telecommunications and Muhammad Nidal al-Sha’ar Minister of Economy. Professionally and socially, each of the individuals in question is embedded within global financial institutions and linked to powerful business networks inside the Gulf.

Grounded in the milieu that has pushed for the opening and liberalization of the Syrian economy since the late 20th century, the ascendance of Husrieh et al speaks to the continuities governing the HTS presidency. It also speaks to how interests and ideological affinities have converged in al-Shara’as Syria, bringing together Syria’s old elite with the leaders of “the Idlib system”3. After spending the majority of the civil war in the Gulf or the west, the Husrieh team saw in al-Shara’a an opportunity to reclaim influence and reinitiate liberalization. For al-Shara’a and his most trusted lieutenants on economic matters—a small crew led by his brother Hazem4 and a handful of businessmen who rose to prominence during HTS’s time in Idlib5—there was a recognition that reformers like Husrieh, Barnieh and Sha’ar could provide their project with legitimacy, credibility, and capacity. This was desperately needed as the HTS old guard worked to rebuild relations with Damascene elites and international business circles. As persons bearing great knowledge not only of the Syrian institutional and legislative landscape but of the World Bank and regional financial structures, the Husrieh cadre were the optimal candidates for institutionalizing the system of governance and reconstruction which al-Shara’a preferred: a system favorable to foreign investment yet under tight, centralized control.6 If this sounds like the state capitalist vision embraced in the Gulf, the resemblance is purposeful. Ahmed al-Shara’a has called those configurations, already to a degree instituted in Idlib, “a successful model to be emulated.”7

The Syrian Ba’ath’s Neoliberal Turn: Integrating into Global Finance to Escape Crisis

One of the ironies of al-Shara’as rule is the extent to which the social and developmental contents of his ambitions track with those evinced by Bashar al-Assad during the early days of his presidency.

When Bashar succeeded his father in June 2000, many anticipated a new dawn for Syria: the “Damascus Spring”. For liberals inside and outside the country especially, the new President heralded the arrival of a new generation of Arab leaders. Bashar’s ideological commitments to the Ba’ath Party’s socialist pretenses being superficial, he was viewed as a catalyst for a neoliberal transformation. The idea that Syria could embrace a “qualified market economy” and “become a part of the world and the world economy”8 took root among wide reaches of the country’s upper classes.

The moment, after all, was one ripe for change. At the dawn of the century, Syrian leaders were confronted with a series of challenges undermining the country’s economic stability. Oil production, the cornerstone of development plans implemented by the Ba’th Party for over thirty years, had declined considerably starting in the mid-1990s.9 The drop in hydrocarbon exports—responsible for two-thirds of Syria’s hard currency flows—coupled with rapid population growth to raise the specter of a structural economic crisis. That danger only heightened once political tensions with the West escalated following George W. Bush’s declaration of the “war on terror” and the assassination of Rafic Hariri in 2005. Bush’s confrontation with the so-called “axis of evil” brought a wave of fresh sanctions onto Syria. Hariri’s killing in Beirut did too, this time from European capitals convinced of Damascus’ guilt.

Squeezed from both sides, Bashar’s regime sought a way out through liberalization and detente: In expanding spaces for private capital, integrating national business circles with those of the Gulf, and resolving tensions with Washington and Brussels, the President’s team thought they could pull the country from the impasse it stood before. At its tenth regional conference in 2005, the Baath Party approved a shift toward a “socialist market economy”.10

Bashar’s Technocrats: The Architects of Financialization in Syria

And well before the troubles of the 2005, the winds were already moving in the direction of liberalization. In accordance with the wishes of business circles and the World Bank, Bashar al-Assad issued, in April 2001, Decree-Law No. 28 authorizing the establishment of private banks. This was a first since the major nationalizations of 1963, which had transferred control of the banking system to the state.11 In the years that followed, the regime issued a whole set of legislation aimed at stimulating investment and regulating banking activities.12 In May 2003, the first licenses were granted to financial entities backed by conglomerates well-established in the Middle Eastern financial system.13

Between 2002 and 2005, Syria witnessed unprecedented growth in its private financial sector, as loans to the private sector increased from 0.7% to 6.9% of the total money supply.14 Damascus was then widely perceived as a land of opportunity by the region’s banking elites, attracted by legislation increasingly favorable to foreign investment.15

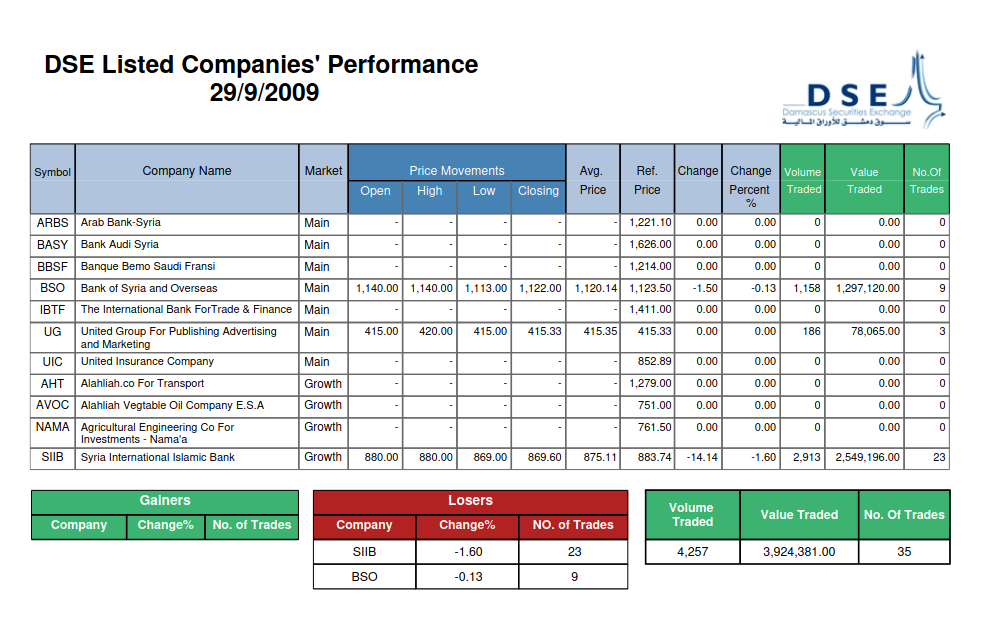

This process of financialization was being driven by a new coterie of technocrats and bankers. Educated either at Western universities or within Arab educational institutions modeled on Western business and management schools, these actors were confident adherents of the World Bank’s strategies for capital market development. In their eyes, the establishment of a brand-new stock exchange in Damascus (the Damascus Securities Exchange—DSE) was a “key strategic goal.”16 To bring the exchange into existence, the Syrian Commission on Financial Markets (SCFMS) reporting directly to the Prime Minister was created in 2006. A working group was also established to expedite progress. Within that working group, two key executives from the SCFMS played a particularly large role: Saker Aslan and Muhammad Yisr Barnieh.

Like most of their colleagues, Aslan and Barnieh had received their initial education at the University of Damascus. Thereafter, Barnieh went on to study international finance at several American universities—Kansas, Washington, and Oklahoma—, completing his academic journey with an internship at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. From there, he joined the Arab Monetary Fund (AMF) in 1996 as an economist.17 Younger than his colleague, Saker Aslan, who coordinated the establishment of the DSE,18 graduated in 2005 with a degree in Information Technology. His technical background initially led him to participate in the modernization of the two main Internet service providers in Syria (Syriatel and SCS-net). In November 2006, he became director of the IT division at SCFMS. As he had limited training in finance at this stage, Aslan took to studying while on the job. This process first took him to Jordan and the Arab Academy for Banking and Financial Sciences,19 then to Syria’s Higher Institute of Business Administration20 before wrapping up at the University of Southampton, where he graduated in 2011 with a MA in International Financial Markets. In January 2008, Aslan was elevated to Deputy CEO of the Damascus Stock Exchange. Fourteen months later, the DSE officially opened for trading.

On both the SCFMS and DSE projects, Barnieh and Aslan worked closely with teams from the London-based consultancy Ernst & Young (E&Y). The latter was contracted with supporting the development of regulatory frameworks which could enhance the functioning of a market economy, E&Y’s Damascus-born consultant Abdelkader Husrieh was responsible for its Syrian dossier. Husrieh was himself an alumnus of the University of Damascus, from where he graduated with a degree law in 1986. Like Barnieh, he also came to his post having spent a number of years within institutions shaped by the U.S. higher education system: Husrieh was trained at the Lebanese American University in the 1980s (1982-1986) before pursuing an Executive MBA in Business Administration at the American University of Beirut (2003-2006). His contributions to the financial reform effort underway were quite significant, particularly so in that he was acting as a private citizen. Throughout, Husrieh collaborated intimately with Aslan and Barnieh on all the major files.21 And Husrieh’s interventions would extend beyond the DSE and SCFMS alone: He also helped redraft key banking laws regulating the nascent private credit sector, advising on legislation related to Islamic finance, central bank governance, and real estate investment..

The Bankers in Damascus: Syria’s Crony Capitalism Turns Toward Gulf Capital

When the DSE launched in March 2009, it was conceived as a means for better steering investment inflows. Traditionally, the capital injections had concentrated in traditional sectors, real estate most of all. The hope of Assad’s policymakers was that the DSE would help move liquidity into conglomerates operating agriculture, media, insurance, and banking.22 For existing shareholders of the companies in question, the new stock exchange therefore represented an opportunity to profit from impending capital inflows.

A number of diversified conglomerates owned by businessmen closed to the Assad clan sold shares at the launch of the DSE. By market capitalization, however, the largest firms traded on the exchange were commercial banks. In accordance with the 2001 law, commercial banks required majority Syrian ownership. This provision would allow entrepreneurial types within the Baath’s networks to gatekeep access to the financial sector—and to capture huge gains form Gulf-originating inflows in so doing. The example of Ahmed Rateb al-Shallah, the first director of the DSE, speaks well to this phenomenon. A long-time ally of the Assad family and head of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce, al-Shallah was the patriarch of the al-Shallah clan—one of Syria’s grand merchant families. An early mover after the 2001 reform to banking law, he helped establish the Bank of Syria and Overseas in 2004. 23 A few years hence with the launch of the DSE—an institution he personally presided over—this positioned al-Shallah to offer up shares to investors predominantly from neighboring Lebanon, and make a quick buck along the way.

Al-Shallah’s experience can also testify to how the banking sector came not only to serve as a vector for integrating Syrian capital into regional networks, but as a means for affording regional capitals a stake in Syria. Through the sale of equity in the Bank of Syria and Overseas, al-Shallah was to become deeply entwined with Lebanon’s Azhari family, majority owners of Blom Bank, just as the Azhari family was to acquire a major asset in Syria. A similar exchange operated through the person of Muhammed Haykal. Apart from being vice-chairman of the Damascus Stock Exchange’s board (and a board member for the Syrian Federation of Chambers of Commerce), Haykal was the director of a UAE-based holding company bearing his family’s name. After the banking sector reforms of 2001, he too would co-found and subsequently vice-chair a new financial institution.24 Called the Arab Bank of Syria, Haykal’s institution was established as the local affiliate of the Amman-based Arab Bank. At the time, Arab Bank was still controlled by the two Palestinian families which birthed it—the Shomans and the Masris—though the Hariri family of Lebanon25 and the Saudi state retained large equity holdings, too.26 In everyone going into business together, such regionally-oriented capitals secured themselves a position in liberalizing Syria, while Haykal and his local allies secured a rent on their mediation of market access and were linked into external circuits of accumulation.

Syrian Finance and the Gulf

The privatization of Syrian banking served as one of the primary mechanisms through which Gulf capitals moved into Syria. Often, they arrived via Lebanese intermediaries. This is easily observed in the case of Bemo Saudi Fransi, which swiftly became one of the largest publicly traded companies in Syria. Though the bank was the Syrian affiliate of the Beirut-based BEMO Bank, 27% of its equity was directly held by Saudi Fransi Bank and just 22% by the mother institution. Inasmuch as Saudi Fransi also owned 10% of the mother institution’s equity, moreover, the Saudi ownership share with Bemo Saudi Fransi was even higher than appeared at first blush. Audi Bank offered another example of a Lebanese bridge institution. Also Beirut-based, Audi Bank set up shop in Damascus through a partnership with the Syrian Bassel Hamwi, a former World Bank business developer who had also played a key role in the DSE’s working group. A look at the local affiliate’s largest shareholders shows the Homaizi family of Kuwait (6.5 % stake), the Kuwaiti ruling family (the al-Sabah; 6% stake), and the al-Nahyan’s of Abu Dhabi (5% stake). The al-Maktoum’s of Dubai also retained an indirect position on Audi Bank Syria through holdings in the Dubai Financial Group.27

In addition to holdings via Lebanese intermediaries, Gulf parties would also take direct stakes in Syria’s financial sector. By 2012, six of the fourteen private banks trading on the DSE had major if not controlling investors from Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

Table: Ownership Shares of Private Banks Listed on the DSE (2012)

| Bank name | Share Capital (S£mn) | Foreign Shareholders |

| 1) Qatar national Bank Syria | 15,000 | Qatar National Bank: 51% |

| 2) Syria International Islamic Bank | 8,499 | Qatar International Islamic Bank: 30% Other Qatari investors: 19% |

| 3) Byblos Bank Syria | 6,120 | Byblos Bank: 52% |

| 4) Bank audi Syria | 5,725 | Bank Audi: 41% |

| 5) International Bank for trade & Finance | 5,250 | Housing Bank for Trade and Finance (Jordan): 49% |

| 6) Arab Bank Syria | 5,050 | Arab Bank: 51% |

| 7) Bank Bemo Saudi Fransi | 5,000 | BEMO: 22% Banque Saudi Fransi: 27%. |

| 8) Cham Bank | 5,000 | Commercial Bank of Kuwait: 32% Islamic Development Bank (Arab League) : 9% |

| 9) Al-Baraka Bank Syria | 4,541 | Al-Baraka Banking Group (Bahrein): 23%; Emirates Islamic Bank: 10% |

| 10) Fransabank Syria | 4,122 | Fransabank (Lebanon): 56% |

| 11) Bank of Syria & overseas | 4,000 | Blom Bank: 49% |

| 12) Bank of Jordan Syria | 3,000 | Bank of Jordan: 49% |

| 13) Syria Gulf Bank | 3,000 | United Gulf Bank (Bahrein / Kuwait): 31% First National Bank (Lebanon): 7% |

| 14) al-Sharq Bank | 2,500 | Banque Libanon-Française: 49% |

All in all, Syria’s capital market liberalization—supercharged through the launching of the DSE—benefited a narrow business elite close to the presidential palace.28 Gulf investors, those best positioned to take advantage of Syria’s opening banking sector, cashed in as well.29 Regime spin promising tahrir al-iqtisad would lift the middle and working classes swiftly proved fictitious. Contemporaneous with the stock market bonanza were structural reductions in public spending and wages and a swift acceleration of deindustrialization.30 These changes primarily affected peri-urban areas, which by 2011 became the main centers of popular uprising.

Revolution, Sanctions and the first integration’s backlash

In 2011, revolution broke out in Syria. Protesters were driven to action by the authoritarian nature of the regime, human rights violations committed by state agents, the nepotism of the country’s economic elites, and deprivations wrought by austerity.31 By March, popular mobilizations would be met with bloody repression.

Less than a year prior, Bashar al-Assad had appointed financial markets expert Muhammad Nidal al-Sha’ar as Minister of Economy and chairman of the national investment authority. Trained in Aleppo and later at George Washington University, al-Sha’ar had built a notable international career as vice president of the Washington based insurance company Johnson and Higgins (1984-1989), Secretary-General of the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions in Bahrain, economic adviser to the World Bank, and a staff trainer at major global exchanges such as those in Singapore, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi. During these years, he “contributed to the development and adoption of international standards”32 across the Middle East, particularly when it came to Islamic finance. As minister, his primary objective was to advance Assad regime’s integration into the global financial system. With the outbreak of the uprising, however, al-Sha’ar’s tasks shifted. Henceforth, his jobs were dual: to prevent the international community from imposing sanctions, and to prepare the economy for such an eventuality.

Through no great fault of his own, on the sanctions front, al-Sha’ar failed in short order. The first restrictions were applied on Syria in May, followed by a more comprehensive regime in September. These measures sent shockwaves through Syria’s business circles. Things only became worse in November, when the Arab League convened in Cairo to discuss freezing the regime’s financial assets and halting all transactions with the Syrian Central Bank. Despite al-Sha’ar’s warnings that these decisions would cause “damage (…) to all sides”,33 the Arab League went forward, with only three countries abstaining, Jordan and Lebanon included. In line with the program developed by the US Treasury, the Arab League’s efforts primarily targeted public entities as well as individuals within the inner circle of the Assad clan.

While Arab and Western states were, with unprecedented force, using economic leverage to put pressure on the Assad clan, criticisms emerged within the Damascus elite regarding the neoliberal policies implemented in the 2000s. Two lines of critique gathered particular force. The first, motivated by the rising inequality evinced within the bourgeoisie, expressed frustration with the effects reform had exerted on the finer threads of Syria’s social fabric. The second lamented how reform had rendered Syria increasingly dependent on foreign capital. As he navigated sanctions, al-Sha’ar tried selling the moment as one for addressing these issues. In an interview four days before the vote on Arab sanctions, he stressed the need to “become more effective in terms of self-sufficiency”.34 The Minister also acknowledged the necessity for the Syrian government to “be more efficient in the allocation of [its] resources” and to “contribute” to the revival of agricultural and industrial sectors, which had been severely damaged by financialization policies and free-trade agreements. Al-Sha’ar remained inflexible, however, regarding underlying commitments to a private sector-led economy. In his words, it was imperative that the business community “operate with flexibility and manage its own affairs.”

Bankers and technocrats throughout the war

Alas, the day was not long for al-Sha’ar and the strand of Syrian liberal he represented. After briefly being dragged into the web of US and EU sanctions, al-Sha’ar left his post in July 2012. Thereafter, he moved between the United States and the UAE, where, drawing on his experience as a former minister and his status as an internationally recognized economist, he focused on consulting, giving lectures, and analyzing international financial developments.

Most of the other technocrats involved in the Assad regime’s early neoliberal turn also decamped for safer pastures.35 Saker Aslan left his post at the DSE in August 2011. Upon leaving Syria, he would work nine years for the Nasdaq exchange and then at Crédit Suisse and Morgan Stanley. In October 2023, Aslan took a senior job at the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange (ADX). Yisr Barnieh continued to rise through the ranks of the Arab Monetary Fund. As the official responsible for developing the region’s financial sectors, his time at the AMF enabled him to establish close ties with the World Bank and major financial actors in the Arab Gulf. Critically, it was during this period that Barnieh collaborated with Abdelrahman al-Hamidy, the unshakable Saudi director of the AMF, accompanying him several times to the World Bank Group Spring Meetings in Washington.

But if the reformers vacated the scene, some of the institutional changes they helped bring to Syria endured. Notable here was the consolidation of private banking. Banking activities did themselves slow to a crawl due to war and legal risk. Nevertheless, the likes of Bank Audi Syria and Bank Bemo Saudi Fransi were never imperiled by the prospects of their assets being frozen, as the international sanctions program imposed on Syria predominantly targeted state-owned banks, government officials, and prominent regime-linked businessmen.36 In some ways, it was life as usual for prominent individuals such as Rateb al-Shallah and Muhammad Haykal.Al-Shallah continued to make regular trips to Damascus and to hold his seat on the BSO board until his death on November 2024. Haykal did step down from his position as vice-chairman of the Arab Bank of Syria in 2011, but he never severed his ties with the institution. He even joined the board of directors in June 2014, a position he held throughout the war37.

Relative to other sectors, finance ended up something of a safe haven during the civil war, a place where Syrian and foreign capitals could park assets until the security and legal environment evolved.38 There were even profits to be had amidst the violence, if comparatively meager ones.39 In the end, virtually all the foreign investors who had been positioned in Syrian banks prior to 2011 held onto their equity throughout the war. Some even acquired more shares, risks be damned.40

Conclusions

The fall of the Assad regime in December 2024 has presented an enormous opportunity for investors and shareholders within the Syrian banking system. It is they who stand to most immediately profit on gains had through the financing of reconstruction and the restoration of normal international exchange. For Ahmed al-Shar’a, keeping these parties vested in his project—and in his ability to deliver these profits—is essential. An unofficial diplomatic corps, they are the ones who can vouch for his government across the Gulf and west and best ensure that sanctions continue to be unwound.

In this context, it is not altogether surprising that al-Shara’a has chosen to turn over economic management to those who once led Assad’s reformist ventures. Abdulsalam Haykal, son of Arab Bank of Syria’s co-founder, UAE businessman, and now head of the Ministry of Telecommunications. Abdelkader Husrieh, Ernst & Young’s man in Syria and now central bank chief. Muhammed Ysir Barnieh, one-time architect of the Damascus Stock Exchange, now helming the Ministry of Finance. Muhammad Nidal al-Sha’ar, the proud liberal reformer back after thirteen years to his stumping grounds at the Ministry of the Economy. Time is a flat circle in Syria.

Since the early day’s of Bashar al-Assad’s reign, there has been a push to more deeply integrate Syria within Gulf-dominated circuits of accumulation. Progress on this track was obstructed by the civil war, but even for al-Assad, the dream was never fully dropped: Once normalization came back on the table in the early 2020s, the bygone President was able to coax the Gulf into a partial return to Syria’s financial markets41.

In many ways, al-Shara’a’ strategy is to build on this momentum: Like his predecessor, he sees capital flows from the Gulf and the broader liberalization of the economy as the sine qua non of recovery. The main goal of al-Shara’a’s team is now to gain the confidence of Western business communities in order to channel their capital into Syria. The lifting of US and EU sanctions as well as reintegration into the SWIFT system represent the firsts tangible success of al-Shara’a’s team, even if numerous issues remain to be addressed before Syria can be fully reintegrated into the global financial system (Critically, cooperation between local and correspondent banks must be strengthened, and securing hard currency deposits is a must)42. The signing of massive investment agreements with the main Arab Gulf powers represents another early win.43

But the question remains: From a social and developmental perspective, what does the kind of recovery being implemented by al-Shara’a et al augur for Syria ? In the 2000s, neoliberal policies helped break the social contract that had long legitimized the Assad clan’s hold on power, paving the way to the uprisings of 2011. Now, many of these designers of those policies are back in the driver’s seat. Making matters more fraught, fourteen years of war have rendered Syria far poorer and more externally dependent than was previously the case.

At this stage, the direction of travel looks to be toward a state capitalist formation modeled on the Gulf, though of course distinct in that it possesses none of the Gulf’s financial resources.44 Al-Shara’a bet is to keep capital happy, be it based at home, in the Gulf or in the West, and hope that the recovery trickles down in such a manner as to secure social peace. Given the current balance of power, the prospects of the trickle down strike as especially bleak. Those empowered to channel capital inflows, after all, are persons embedded within webs of financial, communal, and political interests—webs which make it likely that investment flows will accrue to the benefit of some groups and regions, and not others. That the configuration we observe today might repair a social fabric torn by years of war and sectarian-coded neoliberal rule sadly seems fanciful.

1Interim Syrian president and undisputed leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a coalition of Sunni Islamist rebel militias that has administered Idlib province since 2017 and played a key role in the fall of the regime on December 8, 2024.

2UNDP report presentation, Accelerating Economic Recovery is Critical to Reversing Syria’s Decline and Restoring Stability, February 19, 2025.

3See: Solomon, Richard, Syrian Continuity. The emerging picture of Syria’s political economy, Phenomenal World, October 24, 2025.

4Hazem al-Sharaa is himself a businessman involved in the Idlib system and connected to a US-based multinational company, as a “former PepsiCo general manager in the Iraqi city of Erbil”. In that role, he was also known to have been “a key supplier of soft drinks to Idlib, accor:ding to two people familiar with his past”. See: Timour Azhari and Feras Dalatey, Syria is secretly reshaping its economy. The president’s brother is in charge, Reuters special report, August 7, 2025.

5According Reuters’ investigations (ibid), the former HTS commander Mustapha Qadid “set himself up on the second floor of Syria’s central bank the day after Damascus fell (…) [and] has become known to some Syrian officials and bankers as the ‘shadow governor’, with veto power over decisions by the official governor [Abdulkader Husrieh] two floors above him”.

6See: Solomon, Richard, October 24, 2025. ibid. In this paper, Richard Solomon describes “The Idlib model” as “a striking expression of Syrian neoliberalism”.

7Ahmed al-Shara’a described the Idlib model in these words during his meeting with several representatives of civil society in Idlib, in mid-August 2025. See: Alfeeda, raîs al-jumhûrîa as-saîd Ahmed Al-Shara’a yustaqbalu wafadan min al-fa’âlîât al-mujtama’îa fî muhâfidha idlib, August 13, 2025.

8Khalaf, Roula and Biedermann, Ferry, Ostracism by the West Compounds the Woes of a Decline in Oil Output, Financial Times, November 2, 2005.

9After an apex at 600,000 barrels per day (bpd) in 1996, Syrian oil production started to decline, hitting 500,000 bpd in 2001 and 400,000 in 2010. See: Rashad, Kattan, Mapping the Ailing (but resilient) Syrian Banking Sector, University of St Andrews – Syrian Studies, 2015. p.25 – 26.

10See: Joseph Daher, Syria’s Political Economy, Neoliberal and Authoritarian Dynamics, in Kalamoon, al-Iqtisad al-siyâsî fî sûrîa. 1963-2024. April 2025. p.42.

11More specifically, it allows the establishment of these institutions outside the five free zones that, until that moment, had been the only channels through which foreign banks were permitted to operate in the country.

12Some examples: Law No. 23 of 2002 transferred the supervision of banks from the Ministry of Finance to the Central Bank and established a Money and Credit Council (MCC) to oversee and regulate the activities of private banks; Decree No. 33 of 2005 organized measures to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism; Decree No. 34 imposed banking secrecy on all banks operating in Syria, including those in free zones. See: “Où en est la Syrie”, Compte rendu de la mission effectuée en Syrie par une délégation du Groupe sénatorial France-Syrie du 1 er au 5 avril 2007, June 2007.

13 Lebanese banks (BLOM, BEMO, Audi) and Jordanian banks (Arab Bank, Jordanian Housing for Trade and Finance), which opened branches in Damascus between 2003 and 2005, were soon joined by major Khaleeji banks (Saudi Fransi, allied with BEMO, followed by United Gulf Bank, Qatar National Bank, etc.).

14International Monetary Fund (IMF), SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC—SELECTED ECONOMIC INDICATORS, 2001–2006, Staff Report for the 2006 Article IV Consultation, July 2006.

15In 2007, Decree-Law No. 8 on the promotion of foreign investment in Syria further expanded the rights of foreign investors.

16Knowledge at Wharton, The Damascus Securities Exchange: An Emblem for Syria’s Economic Reform, 18/05/2010. Interview with businessman Bassel Hamwi, former investment officer at the World Bank and director of the Bank Audi Syria, who was part of the small working group coordinating the development of the Damascus Securities Exchange.

17Based in Abu Dhabi, the Arab Monetary Fund was founded in 1979 and is a direct product of the rise of Gulf producer states in the 1970s. In addition to advocating for the harmonization of financial standards across the region, it serves as a historical lever of economic influence for the major players of Gulf capital.

18In the email exchanges concerning the drafting of the DSE, found in the Syria Files on WikiLeaks, Saker Aslan signs as “Board Work Coordinator / Damascus Securities Exchange”. On his LinkedIn profile, he describes himself as the Deputy CEO and IT Director of the DSE between January 2008 and August 2011.

19Institution founded in 1988 by the General Assembly of the Union of Arab Banks, with the aim of training Arab business elites in the functioning of international financial markets. See: https://aambfsye.org/en/about-us.

20Located barely a 15-minute walk from the building that housed the DSE at the time, south of the Barzeh district in northern Damascus, this public institute was founded in 2001 following the model of Western business and management schools, with the aim of training specialized administrative professionals capable of supporting the business sector. It is considered “the first governmental university specialized in business administration” (See: https://hiba.edu.sy/index.php?page=show&ex=2&dir=docs&lang=2&ser=1&cat=596&act=596&).

21Email exchanges revealed in the Syria Files published by WikiLeaks suggest a sustained working relationship between Husrieh and Barnieh : on February 5, 2008, as Ernst & Young delayed the delivery of key documents outlining the regulatory structure of the DSE, Aslan suggested that Barnieh call Husrieh directly to expedite the handover.

22See: Rashad, Kattan, Mapping the Ailing (but resilient) Syrian Banking Sector, University of St Andrews – Syrian Studies, 2015. p.3.

23MEED Editorial, The six key figures in the Syrian banking sector: Adib Mayaleh, Abdullah Dardari, Bassel Hamwi, Rateb, Shallah, Douraid Dergham and Aleppoburn Faisal Kudsi, Middle East business intelligence, September 25, 2008.

24Especially Samer Salah Danial, who still holds a 5 percent stake in ABS today, and was at that time the second-largest retail investor in the private banking sector and a member of the ABS board alongside Haykal. See: Mapping the ailling (but resilient) syrian banking sector, ibid.

25In 2007, the Hariri clan was the main shareholder of the Arab Bank through BankMed, which held 18% of its shares. See: Rosemonde Hatem, “BankMed and Arab Bank Finalize the Acquisition of Turkish Bank MNG,” in Le Commerce du Levant, May 1, 2007. The Hariri clan was represented on the Arab Bank’s board by, Nizak Hariri and Muhammad Hariri, two of the main figures who succeeded Rafik Hariri (d. 2005) at the head of his financial empire. See: Arab Bank Group, Annual Report, 2008. About the rise of the banking and political Hariri clan, see: Samir Legrand,

26Most of the businessmen serving on the Arab Bank’s board at that time, besides their close ties to the Jordanian royal family, were also operating in the Gulf, mainly in Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Bahrain, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. See: Arab Bank Group, Annual Report 2008. ibid.

27Hanieh Adam, Capitalism and Class in the Gulf Arab States, 2011.

28See: Joseph Daher, Syria’s Political Economy, Neoliberal and Authoritarian Dynamics, in Kalamoon, al-Iqtisad al-siyâsî fî sûrîa. 1963-2024. April 2025. This neoliberal shift is part of a deeper dynamic of economic liberalization initiated under Hafez al-Assad. The 2000s marked a real acceleration of this process.

29See: Joseph Daher, Syria’s Political Economy, Neoliberal and Authoritarian Dynamics, in Kalamoon, al-Iqtisad al-siyâsî fî sûrîa. 1963-2024. April 2025. p.42.

30See: Nabil Marzouk, “al-tanmîa al-mafqûda fî sûrîa”, in ‘azmî bashâra (muharriran), khalfîât al-thawra al-sûrîa, dirâsât sûrîa, p.42. The author notes a decline in the share of wages in national income—from 41% of GDP in 2004 to less than 33% in 2008–2009—as well as an increase in income derived from profits and dividends, which mechanically reached more than 67% of GDP at that time. The resulting overall drop in wages contributed to the impoverishment of the Syrian working classes.

31See: Richard Solomon, Ibid.

32See: Nidal al-Shaar’s curriculum vitae on LinkedIn.

33Al-Arabiya with agencies, “Arab League imposes sanctions on Syria ; freezes assets, bans trade, travel”, Dubai, November 27, 2011.

34Syrie, la crise économique fait des ravages sociaux, RTBF, November 23, 2011. Full quotation: “We will let the private sector, which accounts for 73% of our economy, work with flexibility and manage its own affairs. We trust our business community, and the government must limit itself to being a facilitator.“.

35In the initial stages of the civil war, there were some technocrats that maintained closer ties with the Syrian regime. Abdelkader Husrieh not only continued sitting on the board of the Real Estate Finance Commission in Damascus, but served for a year on the board of the Accounting & Auditing Council that was chaired by the Minister of Finance (2013-2014). After 2014, Husrieh ceased any public functions though continued to direct Ernst & Young’s Syria work until the late 2010s.

Re; Ernst & Young, in July 2019, a firm document described Husrieh as the main “partner” (i.e., senior executive) of Ernst & Young Middle East’s Syrian branch. See: Payroll Operations in Europe, the Middle East, India and Africa – Essential Compliance and Reporting Considerations, Ernst & Young, July 2019. Earlier, in June 2016, an International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) document identified Husrieh, via his professional Ernst & Young email address, as the point of contact for the Association of Syrian Certified Accountants, which is described by the IFRS document as “the national professional body for public accountants […] which advises the legislative authorities in the areas of accounting and auditing standards”. See: IFRS STANDARDS—APPLICATION AROUND THE WORLD – JURISDICTIONAL PROFILE: Syria. June 2016.

36The goal of sanctions was to discourage new investors from investing in Syria, not to punish those who had holdings in the country prior to the civil war.

37See: Arab Bank Syria, annual report 2024, and Arab Bank Syria, board members list: https://www.arabbank-syria.sy/index.php?page=show&ex=2&dir=docs&lang=1&ser=1&cat=350&act=350&. (last accessed: 2/11/2025).

38Kattan Rashad, ibid.

39In the third quarter of 2024, after years of efforts toward normalization led by the Assad clan, the sector as a whole posted profits of $59.5 million. See: Report “A Look at Syria’s Banking Sector” BLOMINVEST BANK, Jana Boumatar, May 14, 2025. The figures used in this report are those published by the Union of Arab Banks.

40Rashad Kattan concluded in 2014: “More than three years of a destructive civil war, Syria still appears to these institutions to be a potential lucrative source of income, even if they have to swallow the bitter pill of losses incurred in the country for the time being. Eventually, it can be argued that banks will play an instrumental role in the reconstruction of the country, once this conflict comes to an end.”

41According to the 2023 SCFMS annual report, most of the banks controlled by Gulf networks operating in the Damascus market increased their capital in Syria that year. For instance, BEMO Saudi Fransi raised its capital by 3 billion Syrian pounds, while the Syrian branch of Qatar National Bank increased its capital by 3.63 billion Syrian pounds. That same year, both banks also decided to distribute dividends to their shareholders.

42See Abdulkader Husrieh’s interview for The National: ‘No bank left behind’: Syria’s ties with foreign lenders to resume within weeks. Nada Maucourant Atallah, June 25, 2025. Since their appointment, they have multiplied formal and informal meetings aimed at facilitating Syria’s integration into the global financial system and attracting international capital to the country. On their LinkedIn accounts, Abdelkader Husrieh and Yisr Barnieh regularly publish reports on the meetings they hold with international actors involved in discussions on Syria’s integration into the global financial market, the potential contribution of “the Syrian financial system (…) to revitalizing economic relations between Syria and the United States” (as highlighted in Abdelkader Husrieh’s meeting in August 2025 with representatives of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, including its Chairman Ross Perot Jr. and Steve Lutes, Executive Director for Middle East Affairs), as well as the ‘financing of strategic projects’ intended to support ‘development’ in Syria (as discussed in Yisr Barnieh’s late-October meeting with the leadership of the Saudi Fund for Development).

43Among the key projects: a $7 billion agreement signed with Qatar for investments in the energy sector; a major commitment from the Emirati company DP World in the development of port infrastructure—$800 million investedin the port facilities of Tartus; and Saudi investments amounting to $6.4 billion in reconstruction efforts, including

the first debris-clearing and rebuilding project in the outskirts of Damascus, announced on Sunday, September 7,

2025.

44The project of the sovereign fund, supposedly headed by Hazem al-Shara’a, reflects that trend. See: Timour Azhari and Feras Dalatey, August 7, 2025. Ibid.