Introduction

Both the international press and the academy tend to portray Morocco as an economically dynamic country. This framing derives from the country’s alleged successes in pursuing export-oriented growth, with its achievements in catching up with relatively complex sectors such as the automotive industry held up as a key reference point. Morocco’s so-called “upgrading” within global value chains (GVCs[1]) is said to be associated with a process of “emergence”.[2] In most tellings, also expediting that process are ambitious investment projects connected to the 2030 World Cup, which Rabat secured last year together with Madrid and Lisbon. These projects are in keeping with a long-standing pattern of infrastructure and urban modernization initiatives. Though carried out under the leadership of King Mohammed VI since the mid-2000s, such initiatives have been scaled in the period following the 2008 global financial crisis.

The Generation Z protests that erupted on September 27 and continued throughout October 2025 present a frontal challenge to the narratives surrounding Morocco’s developmental achievements. Starting in Agadir, these protests quickly spread across the country. The grievances fueling the mobilization centered on Morocco’s inadequate education and healthcare systems, the declining performances of which were linked to the state’s prioritization of spending on stadiums, highways, and high-speed trains in preparation for the upcoming football competition. Unsurprisingly, the anger of young Moroccans has been directed primarily against Prime Minister Akhannouch and his close associates in the government—a circle of revolving-door businessmen-politicians well connected to the Royal Family.

In observing the protests, some analysts have noted that Morocco would not be the first country to overestimate the economic benefits of hosting major sporting events—the most common reference being Brazil and the 2016 Olympic Games. In many instances, critiques of this type emphasize that corruption among political elites and/or inefficiencies exacerbate tensions between the population’s social welfare needs and expenditures on megaprojects—which could, in principle, serve as drivers of development. Rarer, however, are examinations probing how deeper developmental issues, such as the structural political-economy contradictions, underlie the Generation Z’s protests and their opposition to the 2030 FIFA World Cup.

In view of this lacuna, this article provides a critical account of the growth model pursued by Morocco over recent decades, using an analysis of its integration into the global automotive industry as an analytical prism. The apparent “success story” of the automotive industry may seem disconnected from the problems of poverty and wasteful public spending denounced by the country’s younger generations; we will forward the case that it is in fact closely intertwined with the protestors’ grievances. This becomes visible once Morocco’s GVC upgrading and selection to host the 2030 FIFA World Cup are interpreted as two dimensions of a peripheral and dependent integration into the world capitalist system.[3]

Integration constitutes a long-term path dependency rooted in colonial domination. In more recent times, it has been advanced through the global restructuring of production as well as the acceleration of neoliberal policies and financialization after the 2008 crisis.[4] Historicized thusly, Morocco’s participation to the global automotive industry can be seen to be subordinated to the prerogatives of transnational corporations (TNCs), whose investment strategies not only obstruct a balanced development process but also rely on widespread impoverishment as a condition for securing inexhaustible supplies of cheap labor. Furthermore, the constraints on growth and balance-of-payments equilibria that subordinated integration perpetuates can be shown to have structurally pushed policymakers to implement fiscal measures that guarantee debt-driven megaprojects—projects more functional to attracting international capital inflows than to addressing the needs of the youth and working classes. Cast in this light, Morocco’s automotive boom, World Cup investment push, and the rage of Generation Z come together as a unified phenomenon.

Morocco’s Automotive Success Story: From the Ingress into the Car Exporters’ Club to the Rise of a North African Electric Battery Powerhouse?

Morocco’s automotive sector serves as the flagship of the so-called métiers globaux (global manufacturing) meant to be propelling the country onto the stage of emerging economies. The sector got moving in 2012 when Renault set up assembly operations for Dacia-branded vehicles within the Tangier Free Zone. The next big development was when PSA’s plants began churning in 2019 (PSA was rebranded Stellantis in 2021). Working out of the Kenitra Free Zone, the firm began by manufacturing the Peugeot 208 on Moroccan’s northern Atlantic coast; following a 2025 plant extension, it also assembles FIAT models there.

Today, Morocco’s automotive exports account for almost a quarter of the country’s total gross exports.[5] In terms of volume, the country produced 524,467 automobile units in 2024.[6] This figure is close to those of automotive hubs that have recently benefited from relocation processes in Centre-Eastern Europe, such as Romania. Notably, it exceeds that of more established car industry centers like Italy, which is increasingly focusing on the manufacturing of premium models at expense of mass produced automobiles.

In 2023, with 116 billion dirhams (around 11.6 billion euros) in export sales, Morocco’s automotive industry officially surpassed the hard currency earnings brought in by phosphates and their derivatives, traditionally the country’s most important sources of external income. Figures concerning value added, alas, are less impressive: the sector’s 2023 share of manufacturing GDP—12.5 percent of the total—makes it only the third most important industry after chemicals (mainly phosphate processing) and agri-food. That said, it is worth noting that the auto sector’s share of the manufacturing GDP pie has doubled since 2014, and since 2022, it has exceeded the shares of the textile and clothing industry, historically one of the country’s leading manufacturing segments.

When considering the automotive industry’s employment impact, one should be cautious about the numbers displayed on government websites, which tend to overstate the sector’s contribution. Assuming the good faith of public institutions, the 250,000 workforce reported by the Ministry of Industry likely refer to total annual hires rather than net job creation within a twelve-month period.[7] The figure of 135,000 workers in 2023 provided by the HCP—the national statistics office—for the transport equipment sector therefore offers a more reliable estimate.[8] Even so, it is a remarkable number, more than tripling over the past fifteen years and making the automotive sector the third-largest manufacturing employer in the country, after the agri-food and textile industries.

Driven by foreign investments, the auto industry—inclusive of vehicle assembly and component manufacture—has also become an important source of capital formation and hard currency capital inflows. Over the past decade, FDI in the sector has on average represented 40% of the annual flow of industry-targeting foreign investment. During this period, Morocco has not only joined the relatively exclusive club of car-producing countries but is also carving out a position in innovative activities such as electric batteries (EB) manufacturing. In 2024, a 1 billion euro investment agreement was signed between the Moroccan state and the Chinese multinational Gotion for the construction of a gigafactory in the Kenitra automotive free zone, which is expected to assemble its first cell in June 2026.[9] And at a nearly monthly frequency, the national and international press report new investments in the EB supply chain. In many cases these are memoranda of understanding rather than finalized investment agreements; however, several companies—mainly headquartered in China—are soon expected to start producing anodes and cathodes in Jorf Lasfar and Tangier.[10] In Tangier, the heart of Morocco’s automotive sector, a new section of the Free Zone is presently under construction for the express purpose of attracting firms producing components for Chinese electric vehicle companies.

Chinese investments also seem to be contributing to improving the sector’s value added in more traditional activities. In 2024, Qinghuangdao-headquartered CITIC Dicastal, established in Kenitra since 2018, tripled its production capacity of aluminum wheel rims[11], while in 2025 Sentury, another Chinese TNC, announced the first investment in tire production on Moroccan soil.[12]

The Dust Under the Carpet of Morocco’s Automotive Success Story: Subordination to Transnational Capital, Dispossession, and Labor Exploitation

If the data just surveyed paints an optimistic picture for the auto industry, it is a picture which actually obscures a great deal. In diving into the details, one finds a development story far less inspiriting.

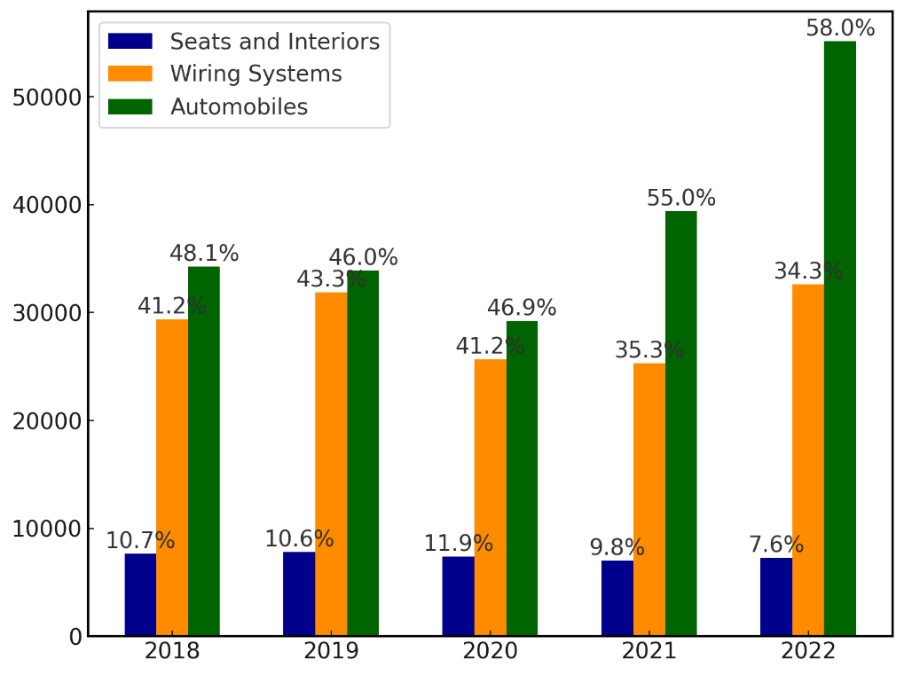

Although finished vehicles account for almost 60% of total automotive production and exports, the bulk of the value chain consists of labor-intensive and low–value-added activities such as the assembly of electric parts—most notably wire harnesses—and textile components for car interiors (Figure 1). By consequence, the auto sector’s contributions to the productivity of the labor force are relatively low. In 2024, consider that the automotive sector’s productivity was only slightly higher than what was observed in relatively low-tech manufacturing industries such as food processing: Value added per worker in the auto sector was 217,000 dirhams; in food processing, the figure was 211,000 dirhams.[13]

The hyperspecialization of Morocco’s production profile also translates into a strong dependence on externally sourced inputs, particularly those with high technological content. Renault, for instance, imports all engines from the EU. While Stellantis does assemble some engines in Kenitra, it restricts its operations to diesel versions and uses components that almost entirely originate from abroad.[14] Generally speaking, moreover, the automotive sector’s domestic content use is fairly low. This is attested in a recent Bank Al-Maghrib report, which documented automotive parts being the second largest category of imports in 2024.[15] “Utility vehicles” is what occupies the second rank, which highlights another problem alongside dependence on foreign inputs: that is the sector’s almost complete concentration in assembling passenger cars for export to the EU.

Figure 1. Morocco’s automotive exports by product category. Data in million dirhams (1 dirham = 0.1 euro). Annotations on bars indicate the percentage of total automotive exports. Source: Lodi 2026; data from Agence Marocaine pour le Développement de l’Investissement et des Exportations (AMDIE).

Such a state of affairs is rooted in the predominance of foreign capital in Morocco’s automotive industry and in the structure of the global automotive sector, which is dominated not only by the major carmakers but also by large transnational groups in the supply chain.[16] The carmakers and supply chain kings both retain interests in relocating production to low-cost countries and in keeping higher–value-added activities within the triad (EU, USA, Japan) in order to preserve their monopolistic positions. Such interests have only deepened in a global context marked by major technological transformations, crises, and the fragmentation of the world market—and by growing competition among old and new centers of accumulation, such as China.[17]

The hierarchical organization of the automotive sector’s global value chains leaves relatively few opportunities for firms from emerging and developing countries. Lacking the know-how, economies of scale, and market access that only global firms possess, companies in the Global South face structural constraints in laying claim to value yielded by production. This is easily observed in Morocco. The decline in the relative capitalization of locally-owned automotive firms—from 17% to 6% of the automotive sector’s total between 2013 and 2023—speaks rather clearly to the difficulties of moving up in the industry. At this stage, Morocco’s auto industry is almost exclusively owned by non-national capitals: French companies Renault and Stellantis dominate in vehicle production while Japanese, U.S., and, to a lesser extent, German groups control the electrical components segment.[18]

The ownership structure of Morocco’s auto industry does not only limit prospects for technological convergence, value capture, and domestic wealth creation: in conjunction with the sector’s disconnection from the rest of the local economy, it also prevents automotive manufacturing from becoming a genuine engine of growth. This is evident from data on the share of manufacturing in GDP and employment, which have remained virtually stagnant at around 11 percent of GDP over the past decade and a half[19], despite the growing importance of investments by carmakers and component manufacturers. Moreover, automotive FDIs are geographically hyper-concentrated, with just two cities—Tangier and Kenitra—accounting for 90 percent of all investments and jobs created.[20]

It should also be noted that the processes which gave rise to Morocco’s (limited) automotive successes—trade liberalization and increasing integration into the EU market—had countervailing effects for Moroccan industry as a whole. Indeed, the combination of current account liberalization and EU integration actually provoked full-blown crises across most of the country’s productive sectors. This was particularly true for the textiles and clothing sectors. Their workforce shrank by one-third after the expiration of the Multi-Fibre Agreement in 2004, which had guaranteed preferential access for Maghreb garments to the EU.[21] And in general, Morocco’s reduction of tariff barriers led to a significant decline in domestic manufacturing value added—a decline only marginally offset by the automotive sector’s expansion, for reasons already detailed.

Critically, trade liberalization—together with lower tariffs on imported wheat, land privatizations, and policy conditionalities placed on product entry to the EU market, such as the removal of subsidies for local producers—also accelerated the crisis of small-scale agriculture and, consequently, a rural exodus to urban areas.[22] And here, the throughlines between the country’s neoliberal turn, the limits of its automotive sector, and the Generation Z protests can begin to come into view.

The Throughlines of Industrial Frailties and Protest

Unable to propel a broader industrial boom, the take-off of Morocco’s auto sector failed to create both the magnitude and type of labor demand needed to healthily absorb the out-migration from the country’s rural areas. It also failed to create the jobs needed to provide a landing spot for the growing number of young people entering the labor market each year. As such, the ranks of those employed in the informal sector expanded despite the rise of automobile manufacturing. At this point, informal employment accounts for roughly 70% of total employment. Nor should contemporaneous expansions to informality and automobile manufacturing be treated as independent phenomena. The competitiveness of automobile manufacturing and the attractiveness of investing in the sector, after all, have hinged on the unevenness of development in Morocco: It is the combination of impoverishment and dispossession in rural areas and the auto sector’s limited spillover effects which underpin the low-wage model that foreign capitals are exploiting.

This causal relation is visible in the composition and compensation of the auto sector’s labor force. The bulk of workers toiling in Moroccan auto manufacturing hail from the country’s agricultural regions. These rural migrants are expressly targeted by the recruitment strategies of TNCS: “Caravans” are regularly sent by the big multinationals to hire from the country’s depressed areas.[23] Having few other options, the workers brought in through these schemes tend to accept low pay. The most common wage in automotive companies is, in fact, the minimum wage—290 euros per month for 48 hours of work. Note that the national living wage is at least 600 euros. In vehicle assembly, conditions are somewhat better than average, with higher wages and a lower incidence of temporary contracts. However, Renault and Stellantis, the dominant actors in vehicle assembly, together employ no more than 10–12% of the total sectoral workforce. 60–70% of workers are employed in the manufacturing of wire harnesses, where exploitation is most severe and the workforce is predominantly precarious and feminized. Virtually the entirety of Morocco’s auto industry is based the country’s Free Zones, moreover, where firings, blacklisting of activists, and occasional police interventions against strikes undermine labor organization.[24]

Could the recent boost in Chinese and electric vehicle–related investments drive a structural transformation of this scenario? It is too soon to properly answer the question. A number of factors deserve our attention, however. First, foreign investments in electric batteries are relatively capital intensive. Furthermore, as is currently the case for car assembly, investments in this industrial line does not guarantee the establishment of an integrated domestic supply chain. On balance, the evidence therefore suggests that battery production will not move Morocco from its general specialization in the most labor-intensive and low–value-added automotive activities.

Second, the EU is presently motivated to improve its capacity in both EV and EB manufacturing. To these ends, Brussels is devoting significant resources. The EU’s 3-billion-euro Electric Battery Alliance program and establishment of relaxed rules for member states willing to subsidize investments in the sector give some indication of the investment.[25] For Morocco, Brussels’ interventions may work at cross-purposes to gaining a foothold in the electrification of the auto sector. While the availability of phosphate and cobalt makes Morocco an advantageous location for some raw materials processing activities, the subsidies in place within Europe will make it hard to challenge Western and Central-Eastern European countries when it comes to higher-tech cell assembly gigafactories.

Third, Morocco does not presently have the capacity to manufacture full electric vehicles, and it is still uncertain that it will acquire this capacity any time soon. Given that 80% of automobiles assembled in Tangier and Kenitra are exported to Europe, where CO₂ emission restrictions will gradually bring an end to traditional car sales by 2035, the electrification of the auto industry could present an existential danger to Morocco. Inasmuch as the EU also appears committed to protecting its own higher–value-added production and countering China’s growing influence in Morocco’s automotive sector—as demonstrated by the recent 40 percent tariffs imposed on wheel rim exports from the North African country—geopolitical and geoeconomic fractures may threaten Morocco, too.[26]

Seen in full, rather than expedite a process of “emergence,” Morocco’s integration into the global automotive sector has reproduced, in new forms, the country’s peripheral and dependent position within global capitalism. This reality is manifest in persistent disequilibria in Morocco’s balance of payments (BoP), disequilibria which offer a crucial lever for pressuring governors into adopting policies privileging the interests of transnational and international capital.

As the data shows, the rise of Morocco as an automotive hub has not meaningfully ameliorated the trade deficits being run up each year. To the contrary, trade deficits have actually grown since the auto sector’s take-off, averaging 9% per annum since the mid-2000s as compares to ~7% per annum in the 1990s and early 2000s.[27] Auto’s negligible impacts on Morocco’s aggregate international exchange can largely be attributed to foreign investments in the sector failing to generate significant growth and industrialization spillovers. In term of consequence, this inability to move the trade ledger forces policymakers to do whatever must be done to insure continuous inflows of external investments and credit.

From the Global Automotive to the FIFA 2030 World Cup: Megaprojects as a – Contradictory – Accommodation to GVC Subordination and Dependency

Over the last two decades, a key policy through which Morocco has secured these inflows is the so-called grands projets (megaprojects) strategy. Since the second half of the 2000s—and particularly after the 2008 crisis—the state has allocated dozens of billions of euros to infrastructure, energy, and real estate development programs. It has done so both to boost aggregate demand in a context of structurally negative net exports and wage repression and to attract foreign financial flows—directly or indirectly. The magnitude of this policy is evident from Morocco’s figures on gross capital formation, which have averaged nearly 30 percent of GDP over the past fifteen years.[28] The bulk of this investment does not come from the private sector but from state-owned entities and enterprises (SOEs), predominantly focusing on carrying out or coordinating construction works.

Importantly, without state-led expenditures in infrastructure such as the Tangier Med port complex, the surge and continuous inflow of automotive FDI would have been unthinkable. It also would not have materialized absent the mobilization of public capital in the form of fiscal incentives and investment subsidies: Renault and Stellantis’ expansions within the free zones of Tangier and Kenitra are very much underwritten by the public purse, and should be counted on the list of state-financed megaprojects. In addition, investments such as the Casablanca–Tangier high-speed rail line and the “urban redevelopment” schemes in major Moroccan cities, such as the Bouregreg Valley project in Rabat[29], have crucially contributed to Morocco’s relaunching as an attractive destination for wealthy foreigners, supporting FDI in real estate in addition to tourism revenues.

Together with the state itself, Morocco’s grand projects have involved major domestic banks, insurance groups, and construction firms. On the latter, note that many of these entities are controlled by the King’s own holding company and a narrow circle of big businessmen who rose to prominence during the mid-2000s privatizations, a social fraction within which Prime Minister Akhannouch is a leading member.[30]

The strengthening of this small elite through crony relations and public contracts should not, however, be viewed through prism of corruption, at least not exclusively. This is because it is rooted in a logic that Bonizzi et al. have defined as “subordinated financialization,” and is therefore inextricable from Morocco’s peripheral and dependent position in the global economy. Indeed, the ascent of these domestic capitals have actually opened abundant opportunities for foreign investors to profit seek in Morocco: The nurturing of so-called “national champions”[31] through megaproject-related procurements has supercharged the Casablanca Stock Exchange—the second largest African equities market in capitalization after Johannesburg—and in so doing, created plenty of space for speculation. Grand projets surrounding the 2030 FIFA World Cup have further charged this dynamic. Since January 2025, the stock market index for Casablanca’s exchange has leaped 30%, with many investors hoping that World Cup developments will uplift the country’s derivatives market in the coming period.[32]

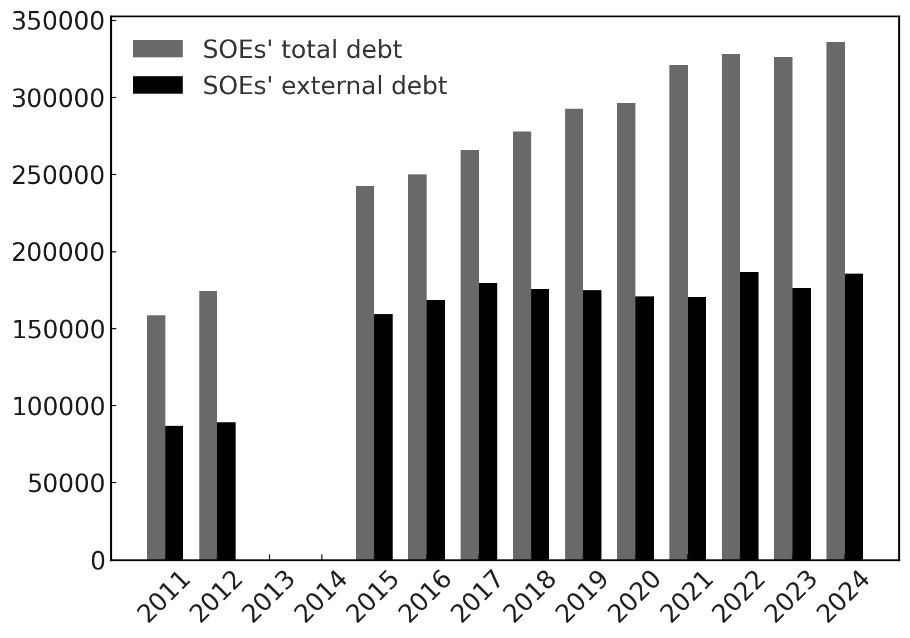

As important as private capital flows have been to Morocco’s grand projet strategy, they actually pale in importance to those brought in from international financial institutions (the World Bank above all), EU countries, and Gulf states. Billions in loans from these multilateral and bilateral creditors have been the basis for all the biggest infrastructure investments, from the already mentioned Tangier Med to the giant Solar Plant Noor in Ouarzazate.[33] Incidentally, the latter contributed more to water distress in this southeastern semi-desert region than to reducing the country’s dependence on energy imports.[34] And while these loans have had positive effects on the BoP, at least in the short-term, over time they have contributed to the debt-dependent nature of Morocco’s entire growth model. Between 2016 and 2024, the liabilities of SOEs involved in the grands projets have soared from 150 billion dirhams to 336 billion (Figure 2). This is equal to roughly 30% of public debt—whose share of GDP peaked at 70% after the COVID crisis—and more than half of its external component, since roughly 60% of SOEs’ financing continues to come from foreign sources.[35]

Figure 2. Debt of Moroccan SOEs. Data in billion dirhams (1 dirham = 0.1 euro). Sources: Author’s elaboration based on Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances (available editions of Rapport sur la Dette Publique and Rapport sur les Établissements et les Entreprises Publiques, 2013–2025).

Importantly, even when SoE liabilities are not directly accounted for in the treasury budget, they are generally still backed by the state. This means when the country’s SoEs seek to refinance obligations, creditors do not only look at their books but the books of the state. Hence the pressure policymakers face toward adopting austerity: It is part and parcel of the state’s serving as guarantor for the grand projets. Also compelling policymakers to adopt austerity were more contingent developments set into motion during the COVID pandemic. When the U.S. and EU central banks raised interest rates to respond to inflation spirals, they helped drive foreign capital from Morocco. In conjunction with falling exports and tourism receipts during the lockdown period, this ultimately forced the Moroccan government to subscribe to a 3-billion SDR lending program with the IMF in 2020, an arrangement followed up by top-up credit lines of 5 and 4.5 billion SDR in 2023 and 2025, respectively.[36] As is customary, conditionalities attached to the loan included fiscal consolidation.

In comparative terms, Morocco has weathered austerity pressure relatively well. Over the past few years, the state budget for education and healthcare—whose shortcomings triggered the Gen Z protests—was not directly cut. The former indeed shifted from an average of 5% of GDP in the 2010s to 6% after 2020. Nevertheless, these allocations did nothing to change the fact that 30% of education expenditures remain in charge of families, nearly double the average burden recorded in OECD countries.[37] Furthermore, the burden may soon get worse. As Moroccan unions have denounced while striking in support of Gen Z protests last October, reform 59.24 is likely to drive up household expenditures on education by growing the market share of private institutions within tertiary education.[38] As for healthcare, state funding has stagnated at around 7% of total government expenditures over the last two decades.[39] This sum is not only lower than the 12% recommended by the World Health Organization, but also less than what the government disburses (8% total expenditures in 2024) to pay interest on its debts.[40]

Conclusions

There is no doubt that the 2030 World Cup will help revamp Morocco’s grands projets strategy. At least 6 billion euros in public money is presently allocated for investments in stadiums and other infrastructures, most notably airports and high-speed railways unaffordable for most Moroccans. This capital has largely been debt financed, predominantly through a 2025 Eurobond issuance but also through the borrowing of SoEs.[41] Mobilized at a time when Morocco has promised the IMF it will cut the public deficit from the current 4.5% to approximately 3% by 2030, these investments are poised to further squeeze the public welfare system.

Just as consequently, the continuation of the grands projets strategy seems unlikely to resolve the structural problems affecting the Moroccan economy—not least those entailing the strong asymmetry between the few regions relatively well integrated into the global economy and the majority of depressed rural areas destined to remain reservoirs of cheap labor for Western- and China-headquartered TNCs. As figures from the Ministry of Finance report, over the 2015–2025 period, the three regions of Casablanca, Rabat-Kenitra, and Tanger-Tetouan have benefited from 60% of total SOE investments.[42] The capital initiated to support World Cup-related projects follows this same geographic distribution.[43]

The causes of the Gen Z protests can be conceived narrowly. In the most immediate sense, these were mobilizations precipitated by declines in social services quality and anger at the public moneys being prioritized for the World Cup. But the protests can also be traced back to the larger model of dependent and subordinate capitalist development being pursued in Morocco. The protests can also show how notional successes—like the automobile industry’s take-off, large infrastructure projects, and being awarded the World Cup—connect to the marginalization of the many. As such, like other mass movements led by young people across the Global South, Morocco’s Gen Z protests demand reflection on the country’s political economy itself. When peripherality so harshly limits the gains that can be had through integration within global systems of production, exchange, and finance, a more radical way may in fact be the only viable path forward.

This publication has been supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. The positions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

Photo Credit: Kingdom of Morocco Ministry of Industry and Trade

[1] Gereffi, G. 2019. “Economic Upgrading in Global Value Chains.” In Handbook on Global Value Chains, edited by Ponte S. at al., 240-254. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

[2] Sandberg, E., and S. Binder. 2020. Mohammed VI’s Strategies for Moroccan Economic Development. New York: Routledge.

[3] Amin, S. Imperialism and Unequal Development: Marxist Theory and Contemporary Capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977.

[4] Smith, J. 2016. Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century: Globalization, Super-Exploitation, and Capitalism’s Final Crisis. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Bonizzi, B.; Kaltenbrunner, A. and J. Powell. 2019. “Subordinate financialization in emerging capitalist economies,” Greenwich Papers in Political Economy, Greenwhich: University of Greenwich. Greenwich Political Economy Research Centre. https://ideas.repec.org/p/gpe/wpaper/23044.html.

[5] HCP (Haut Commissariat au Plan.) 2024. ‘Les Comptes Nationaux Provisoires 2023, Base 2014 (Rapport Complet)”. https://www.hcp.ma/Les-comptes-nationaux-provisoires-2023-Base-2014-Rapportcomplet_a3891.html.

[6] Data Furnished by Organisation Internationle des Constructeurs Automobiles

[7] MIC (Ministère de l’Industrie et du Commerce) n. d. “Baromètre de l’industrie nationale : l’industrie marocaine franchit un nouveau cap en 2024.” https://www.mcinet.gov.ma/fr/actualites/barometre-de-lindustrie-nationale-lindustrie-marocaine-franchit-un-nouveau-cap-en-2024.

[8] See: HCP 2024

[9] Lodi, L. 2025. “A New ‘Emergent’ Powerhouse in the Global Automotive? Uneven Development, Exploitation, and Dependency in Morocco’s Car Industry.” Middle East Critique.

[10] Sbiti, S. 2024. “Comment et de quoi se constitute le futuer ecosystème des battéries electriques au Maroc?”. Le Desk. https://ledesk.ma/datadesk/comment-et-de-quoi-se-constitue-le-futur-ecosysteme-des-gigafactories-au-maroc/.

Ben Yahmed, M. 2025. “À Jorf Lasfar, le Maroc entre dans la course mondiale aux batteries électriques”. Jeune Afrique. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1701036/economie-entreprises/maroc-chine-a-jorf-lasfar-cngr-et-al-mada-posent-la-premiere-pierre-dune-filiere-batterie-africaine/.

[11] “Le Chinois Citic Dicastal construit sa 3ᵉ usine au Maroc, pour un investissement de 1,8 MMDH.” 2024. Le Desk. https://ledesk.ma/2022/02/16/le-chinois-citic-dicastal-construit-sa-3eme-usine-au-maroc-pour-un-investissement-de-18-mmdh/.

[12] Hooper, O. 2025. “Chinese Tire Company to Invest Nearly $300 Million in Moroccan Factory.” Morocco World News. https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2023/01/37572/chinese-tire-company-to-invest-nearly-300-million-in-moroccan-factory/.

[13] See: HCP (2024)

[14] Lodi (2025)

[15] Bank Al‑Maghrib. 2025. Rapport annuel 2024. Rabat: Bank Al-Maghrib. https://www.bkam.ma/Publications-et-recherche/Publications-institutionnelles/Rapport-annuel-presente-a-sm-le-roi/Rapport-annuel-2024.

[16] Wong, W. K. 2018. Automotive Global Value Chain: The Rise of Mega Suppliers. London: Routledge.

[17] Krzywdzinski, M.; Lechowski, G.; Humphrey, J. and T. Pardi, eds. 2025. Global Shifts in the Automotive Sector: Markets, Firms and Technologies in the Age of Geopolitical Disruption. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

[18] Lodi (2025)

[19] HCP (2024)

[20] MIC (Ministère de l’Industrie et du Commerce). 2024. “Baromètre de l’industrie marocaine”. https://marocpme.gov.ma/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Barometre-delindustrie-.pdf.

[21] HCP (Haut Commissariat au Plan). 2014. “La hausse des exportations du textile a-t-elle soutenu l’emploi de la branche en 2014?” https://www.hcp.ma/file/231296/.

[22] Akesbi, N. 2023. Maroc : une économie sous plafond de verre : des origines à la crise Covid-19. Rabat: Revue marocaine des sciences politiques et sociales.

[23] Bidet, A; Ouédraogo, J-B.; Rot, G.; and Vatin, F. 2017. “Une nouvelle économie politique de l’industrie : l’essor du salariat mondialisé dans la zone franche de Tanger.” Revue marocaine des sciences politiques et sociales 14: 221-240.

[24] Lodi (2025).

[25] European Battery Alliance (EBA 250). 2023. “Strongly Welcomes New EU Financial Stimulus of e3bn to Boost Growth of the Battery Industry. European Battery Alliance.” https://www. eba250.com/european-battery-alliance-eba-250-strongly-welcomes-new-eu-financial-stimulusof-e3bn-to-boost-growth-of-the-battery-industry/.

[26] Mousjid, B. 2025b “Du cobalt au lithium, la Chine prend racine au Maroc… et Paris s’en méfie.” Jeune Afrique, 6 Oct. 2025.

[27] World Bank n.d. (a.). “External balance of Good and Services – Morocco”. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.RSB.GNFS.ZS?locations=MA.

[28] World Bank. n. d. (b.) “Gross capital formation (% of GDP) – Morocco” 2025. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.GDI.TOTL.ZS?locations=MA.

[29] Bogaert, K. 2019. Globalized Authoritarianism: Megaprojects, Slums, and Class Relations in Urban Morocco. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[30] Aksebi (2023);

[31] Mhaoud, S. 2018. Les champions nationaux : l’équation du développement au Maroc. Casablanca: En Toutes Lettres.

[32] Aublanc, A. 2025 “Maroc : la Bourse de Casablanca bat des records, au risque de l’explosion d’une possible bulle spéculative.” Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/07/25/maroc-la-bourse-de-casablanca-bat-des-records-au-risque-de-l-explosion-d-une-possible-bulle-speculative_6623887_3212.html.

[33] See: Sandberg and Binder (2020).

[34] Moustakbal, J. 2022. “Le secteur énergétique marocain toujours dépendant du privé.” Orient XXI. https://orientxxi.info/magazine/le-secteur-energetique-marocain-toujours-dependant-du-prive,5268.

[35] Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances (MEF). Rapport sur la situation économique et financière du Maroc 2023. Rabat: MEF, 2024. https://www.chambredesrepresentants.ma/sites/default/files/2024-10/08-%20Rapport%20Dette%20publique_Fr.pdf.

[36] IMF (International Monetary Fund.) 2025. Morocco: 2025 Article IV Consultation and Third Review Under the Arrangement Under the Resilience and Sustainability Facility – Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Morocco, Staff Country Report No. 2025/087. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

[37] Ibriz, S. 2020. “Les Marocains assurent 30 % du coût de l’éducation, le double de la moyenne OCDE.” Médias24. https://medias24.com/2020/12/07/les-marocains-assurent-30-du-cout-de-leducation-le-double-de-la-moyenne-ocd/.

[38] Staff Writer, “Maroc : l’enseignement supérieur en grève rejoint les revendications des jeunes de la GenZ 212,”. 2025. RFI Afrique, 8 octobre 2025.

[39] World Bank. n. d. (c.) “Domestic general government health expenditure (% of general government expenditure) – Morocco.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.GHED.GE.ZS?locations=MA.

[40] IMF (2025).

[41] Mousjid (2025)

[42] Azeroual, M. 2025. “Investissement public au Maroc : moteur sous pression.” Librentreprise. https://librentreprise.ma/2025/05/28/investissement-public-au-maroc-moteur-sous-pression/.

[43] Mousjid (2025).