Order, reform, and stability: such might be the byword of the Hashemite monarchy, which seemingly weathered the Arab Spring with no incidents of violence. The government managed to skillfully showcase a gradual ‘democratization’ of the system in response to popular demand for political change. However, the severe crackdown on the opposition throughout 2020 shed light on a coercive system, the functioning of which was long invisibilized, together with its opponents. The condemnation of this repression as well as the varied and continuing demands of its society seem to bear out the end of the enchanted interlude that the monarchy had enjoyed after 2011.

In Jordan, the crackdown was as harsh as it was unexpected. In 2020, at the height of summer, the Court of Cassation banned the country’s main opposition movement, the Muslim Brotherhood. A few weeks later, authorities announced the shutdown of the teachers’ union, and around one thousand of its members were arrested for participating in protests. In addition to this major police intervention, Jordanian journalists were forbidden from reporting on the teachers’ protests; about fifteen were arrested for violating this order. The last episode in this series of repressive actions was the arrest of renowned cartoonist Emad Hajjaj after he published a cartoon mocking the normalization of relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates.

This series of events clashes with the image that Jordan strives to present, that of a stable Middle-Eastern country, with a strong record of economic and political reforms. But the country’s recent history shows that its political system relies on the coercion and repression of dissenting voices. The somber fiftieth anniversary of the Black September events in 1970 between the Jordanian military and thousands of Palestinian fighters, is a reminder of the regime’s long history of political violence. Social and political protests were also suppressed for decades under martial law, though with greater subtlety.

Starting with the phase of ‘democratic opening’ in the 1990s, control over dissenting opinions became more discreet. The electoral system that was chosen in 1993 led to a weakening of the opposition movements, and journalists were closely supervised to ensure they would echo the official narrative of a country ‘in the process of democratization’.

Part 1. A political power shaped by control

Thus, the 2020 crackdowns are not so much a reflection of a deepening authoritarianism, as a surfacing of practices that had hitherto been hidden. This analysis focuses on the factors behind the unmasking of the coercive strategies deployed by the ruling power. The narrative of the never-ending ‘reform’ of Jordan’s political system, claimed to be underway since the 1990s, has gradually lost its credibility, in the face of continued repression of political parties, trade unions, and the media. Those coercive practices progressively came to light in three major stages.

The first stage was a long term process that began just after the popular uprisings of the Arab Spring. While they promptly announced and implemented political reforms, the authorities simultaneously sought to weaken opposition voices, especially that of the Muslim Brotherhood. The second stage began in 2019, when about fifteen political activists were arrested for posting messages on social media that criticized Jordan’s regime or the King himself. The third stage is the recent repression of journalists, of the teachers’ union and of the Muslim Brotherhood yet again.

The economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic led to a shift in the authorities’ strategy towards stricter, and thus more visible, preventive repression. Their aim is to stifle any potential social movement, even at the expense of their image as an increasingly democratic country. At the same time, in response to the increasingly strident demands voiced by established political groups, the central authorities tightened their grip on the country through a broader crackdown intended to reassert their control. The latest stage thus seems to mark the end of an ‘enchanted interlude’ for the Hashemite monarchy, which since 2011 had managed to maintain its image as a regime that could both control and appease its people and popular demands without violence.

The 2020 repression is but the most recent and visible manifestation of the longstanding coercive system that allowed Jordanian authorities to permanently establish their power. For decades, this authoritarian regime has relied on discreet methods in order not to jeopardize the image of a reformist government that they marketed to their Western allies.

Discreet but systemic repression

Since the end of the 1990s, development institutions have considered Jordan to be a country ‘in the process of democratization’, making it a favored partner for Western powers in the Middle-East. This status stems partly from the fact that Jordan was the second Arab state to sign a peace treaty with Israel, in 1994. King Abdullah II has ruled the country since the death of his father Hussein in 1999, and has cultivated an image as a modern monarch in his approach toward government and his attitude toward the people. Desirous of maintaining the impression of a stable and reformist country, he responded to the 2011 Arab Spring protests – which, in Jordan, mainly called for political reforms1 – by amending the Constitution, dissolving the government, and creating an independent electoral commission, to guarantee democratic elections.

In July 2018, during the month of Ramadan, thousands of people took to the streets once again in an echo of the 2011 protests. This time, they were peacefully opposing a tax reform and a rise in fuel and electricity prices. While images of police officers laughing with protesters (in Arabic) went viral on social media, the King reacted to this lower and middle-class social movement by vehemently criticizing the government’s policies, leading to the resignation of the Prime Minister at the time.

In a way, those two events reveal the architecture of Jordan’s political system, in which the King has a central and overarching position. He is the supreme leader of the armed forces and holds executive power. In 2016, his authority was expanded by an amendment to the Constitution allowing him to appoint the state’s highest officials without the approval of the Prime Minister. He ratifies and promulgates laws, has the power to dissolve the Parliament, and establishes the electoral timetable. Under his authority, the Royal Court (al-diwan al-malaki) oversees the implementation of his decisions and initiatives. The inner workings of the court and daily activities of its committees are kept relatively secret.

Contrary to the Court and the King, the government, whose role is mostly limited to representation and policy execution, is a constant target of media attention. Currently, it is mainly composed of technocrats and must, above all else, ensure the equal distribution of ministries among the social elites of the country’s twelve governorates. The government also recruits through co-optation, which allows it to assimilate some political opponents and members of civil society. As for the Parliament, consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate, it is a remarkably weak and marginal institution. For instance, it is impossible for representatives to propose a bill if the government has not signed off on it first. Lastly, Jordan’s intelligence service is the centerpiece of the political system, although it maintains a low profile. Since the early 2000s, its powers have been expanded yet further in the context of the fight against terrorism (see HumanRights Watch report).

Jordan’s political system relies on a highly centralized, personalized power structure that favors authoritarianism. The intense repression of summer 2020 revealed the extent of the coercive apparatus, which had been hidden until then behind the image of a reformist country that formed the basis for the Kingdom’s outward stance. The control of all types of opposition – political groups, the media, unions, and organizations- is exerted through overt or covert repression at the hands of the military, the police, and the intelligence services.

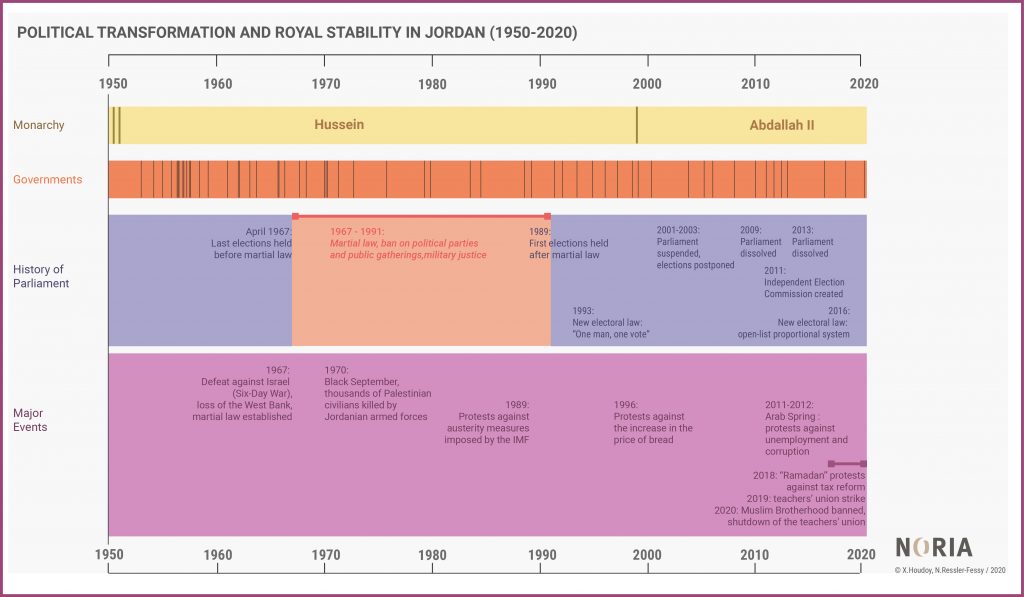

This system was first established by martial law, an extraordinary measure taken in 1967 by King Hussein following the Six-Day War, to be abrogated in 1991. The law was justified by the need to strengthen the state against the growing influence of Palestinian forces in the country, and it led to the prohibition of political parties, the cancelation of elections and direct control over civil society for more than three decades.

This institutionalized repression peaked during the 1970 Black September confrontation, when the Jordanian Armed Forces killed 3,000 to 7,000 Palestinians2 – mainly civilians – who were living in the country. Fearing a political coup orchestrated by the Palestine Liberation Organization’s feddayins (members of armed groups), King Hussein, emboldened by the West’s support, violently crushed the social movement and drove the Palestinian organization out of the country and into Lebanon.

Twenty years later, in 1989, under pressure from strong large-scale protests and the admonition of international donors, who were prominent supporters of the monarchy, Jordan began a ‘democratization’ process. Hussein allowed political parties to reemerge; for the first time since 1967, general elections were held, and freedom of the press was guaranteed by law.

Democratizing for greater control

After 1990, the political authorities adopted a new repression strategy. Protests were no longer systematically suppressed, but they were targeted and inconspicuously controlled. The government also tried to respond to protests with social reforms. The massive protests of 1989 and 1996 which began in two Southern cities – Ma’an and Kerak respectively – illustrated this new approach. The popular backlash against the rise in oil and bread prices was still suppressed (20 dead in 1989, 200 arrests in 1996), but it led to the announcement of new political reforms and the repeal of martial law.

This reformist façade gradually molded Jordan’s national image over the last three decades. It went hand in hand with the invisibilization of repressive actions, especially after the Arab Spring, allowing public authorities to both preserve the monarchy’s power and contain protest movements. Under this strategy, the Royal Court demanded the resignation of the government twice, in 2011 and in 2018, to assuage protesters’ anger. However, the undermining of opposition forces continued, although more covertly than before.

In addition to all of the above, the electoral system is also used as a tool of coercion. After the Islamists – the biggest opposition movement in the country – won the general elections by a significant margin in 1989, with about 40% of Parliamentary seats, a royal decree replaced the system of multiple voting with the sawt al wahedou, the ‘one-man-one-vote’ or single non-transferable voting system. In 1989, voters could cast as many ballots as there were seats up for election in their constituency. But starting in 1993, they could only vote for one candidate, and they often chose a member of their own tribe or one of their relatives, who were accessible middlemen and with whom they had stronger bonds of mutual dependence.

This new voting system led to the high prevalence of votes for tribal candidates, rather than for political groups. Its purpose is to encourage a personal bond between voters and office-seekers, rather than a party-based link. This allowed the authorities to limit the number of votes cast in favor of political parties, especially opposition groups such as left-wing parties or the Islamic Action Front (IAF), the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood. With only ten representatives out of 130, the IAF was the most prominent party in the House of Representatives (majlis al-nuwwab) between 2016 and 2020.

Control of the political arena is also ensured by electoral district boundaries, which reinforce the perception of elections as a patronage system and deepen inequalities between ‘Transjordanians3’, seen as supporters of the regime, and Jordanians of Palestinian descent, who are considered potential opponents. Since the reign of King Hussein (1952-1999), Jordanian authorities have tried to secure the loyalty of Transjordanians through patronage, by redistributing financial and symbolic resources, for instance in the form of public office jobs.

Electoral boundaries benefit majority-Transjordanian urban and rural areas, ensuring their over-representation in Parliament. In 1989, the new electoral cycle coincided with a national economic and political crisis, leading the regime to treat the Parliament as an institution made up of seats based on various levels of patronage, especially when it came to the Transjordanian regions. Representatives became brokers between the state and the population, granting select citizens preferential access to public funds, often in the form of employment and scholarships.

The difference in voter turnout between governorates shows that Transjordanians are the main beneficiaries of the system, as they hold more than 75% seats while representing less than 50% of the total population. The Amman and Zarqa Governorates, which are home to most of the Palestinians and Jordanians of Palestinian origin in Jordan, always register the lowest turnouts.

The rationale behind the electoral boundaries, and their effects, are summed up below by a former pro-Palestinian activist who is now a member of the left-wing Jordanian Social Democratic Party:

‘We believe that the best system would be to have a single national constituency, to allow party members and social and political movements to work together on a national list of candidates, and then be divided into groups in Parliament. But in Jordan we encounter a demographic issue, because if we only had one constituency for general elections, then there would be a risk that all of the representatives might come from the capital. And you know that in Amman (…) there is a Palestinian majority, so the demographic representation in Parliament would change and that frightens Jordanians.’

In 2016, a proportional voting system was established by law in order to satisfy one of the major demands of the 2011 protesters. The new system allows voters to choose as many candidates as there are seats in their constituencies, but the country’s constituency boundaries were kept in place. The same activist adds:

‘Now we have a proportional system, but it is based on small constituencies, whereas a proportional system should be based on large constituencies (…) But they don’t want any large political groups in Parliament. They want people to come as individuals, because in this new system it is hard for a list of candidates to win more than one seat per constituency.’

As a result, over the years, the Parliament gradually lost its credibility as an institution. During the summer 2018 protests, Jordanians were chanting slogans such as ‘In Jordan, we have a convenience store we call Parliament’ (في الأردن عنّا دكان، بسمّوها برلمان). Intelligence services are also often accused of interfering with election results4.

The Parliament is generally described as mere theatre, as it has no legislative role or control over the government, partly because representatives have to bend to the will of the ministries, which they consult every week in order to satisfy voters’ clientelist requests. To remain in the government’s good graces, representatives must support the executive branch when voting for amendments and important bills. Some of the representatives themselves share this critical view of the system, attributing their lack of political power to their clientelist dependency on the government. For example, a representative explains:

‘My position as a representative is difficult. Sometimes I have to be very weak when putting questions to a minister, because I know that I will have to ask him for favors for my voters the next day. If we weren’t constantly asking for favors, we would be stronger. But if I go and see a minister and ask him “Could you please transfer this employee to this section,” and he grants me that favor, then I won’t be able to stand up to him with the other representatives during the question period. We are always asking for favors, and many representatives suffer from that.’

Information control

In addition to undermining opposition forces, Jordan’s coercive system relies on control over information production in the country. Two strategies are used: making sure that the official version of events is as widespread as possible, and weakening or discrediting alternative voices. The official version is mainly disseminated by major daily newspapers such as Al-Rai and Ad-Dustour, which act as mouthpieces for political authorities.

Significant financial resources are invested to encourage young Jordanian journalists to contribute to a positive image of the country, as illustrated by the creation of a new public TV channel, Al-Mamlaka (‘The Kingdom’), where journalists are paid almost 800 Jordanian dinars (1 000€), nearly three times the average pay in the profession.

The close relationship between the Court and the media is not new. In 1976, King Hussein created the Jordan Times, the first English-language newspaper for foreign readers, which was quickly dubbed ‘The King’s newspaper’. A former journalist summarizes the links between the Jordan Times and political authorities:

‘As a journalist, my job was to translate the King’s messages for the world (…) To be honest I mainly reported on what the King did or said (…) We sometimes received a phone call in the evening to put some official statement on the front page (…), but we didn’t let ourselves be pushed around, we had to negotiate everyday with the political power, we had to compromise.’

In 2006, the Royal Court expanded its influence on the media by establishing the Jordan Media Institute (JMI), which was founded by Princess Rym (wife of the current king’s stepbrother, Prince Ali), and has become a reference for journalism training centers.

At the same time, public authorities resorted to a series of strategies to weaken and marginalize independent journalism. The Press and Publications Law was adopted in 1998 and it allowed the government to regulate the media by arbitrarily granting authorizations to publish. The law was used as a justification to close down more than 250 news websites in 2013 on the grounds that they were not in compliance with official conditions.

The Electronic Crime Law, amended in 2018, is another of the favorite tools of the authorities. This law was allegedly adopted to combat ‘hate speech’ – which remains a vague concept in the legal text – online, and it allows the arrest and arbitrary imprisonment of anyone who posts messages on social media that are considered politically or morally unacceptable. Control of the internet is all the more important politically as Jordanians now get their information online, mostly on Facebook (5.5 million accounts for 10 million inhabitants) in order to bypass the censorship imposed on public media.

On the internet, Jordanians can access opinion articles written by journalists that would be censored in national newspapers, posts by activists and political campaigners, and foreign media articles not subject to national media control. Following this shift of the public debate toward social media, the Electronic Crime Law and the Anti-Terrorism Law were recently amended to permit the arrest of dozens of political opponents, journalists, and activists for messages that they had posted on Facebook or on the application Whatsapp.

Since it was amended in 2014, the Anti-Terrorism Law has frequently been used against political opponents accused of ‘harming [Jordan’s] relationship with a foreign country’ (art. 2) or of ‘disturbing the public order’ (art.3), both actions being considered terrorism from then on.

Most journalists have been driven to self-censorship for fear of prosecution and the public humiliation campaigns that have been waged against dissident voices, while some citizens have had to creatively reinvent public debate in other ways. For instance, in 2013, a young jordanian co-founded Al-Hudood, a critical and satirical news publication written in Arabic and modeled after websites such as The Onion in the United-Kingdom or Le Gorafi in France. He explains the origins of Al-Hudood, which is now followed by nearly half a million people on Facebook:

‘People want to talk about politics, but they can’t, so we found a back-door way to open the debate: we don’t do journalism, we don’t do news, our purpose is to make people laugh and cry through satirical articles, so that people can reflect on politics, and to normalize satire in the public debate (…) We also want to criticize media coverage, tell traditional media journalists that they aren’t doing their job.’

Part 2. Repression after the Spring

Although coercion is enshrined in the very heart of the Jordanian regime, its coercive practices have become increasingly harsh and visible since the Arab Spring. The first target was the Muslim Brotherhood, one of the major established opposition groups. Then, the government focused on individual dissenters, especially through the Electronic Crime Law, which led to the arrest of about fifteen activists in 2019. The year 2020 marks a new phase in the unmasking of state repression, with the decision to shut down the teachers’ union and the detention of more than one thousand of its members.

Repressive practices more visible

The Muslim Brotherhood was one of the first main targets of the Jordanian government, echoing the repression they suffered in Egypt and Saudi Arabia starting in 2013. They had a personal enemy in Fayçal al Shawbaki, the new head of intelligence services, appointed a few years earlier5.

Some of the Brothers, called reformists, launched the ‘ZamZam’ initiative in 2012 (named after the hotel where the launch meeting took place), bringing together more than 500 Jordanian public figures who signed a charter calling for political reform. In 2015, Jordanian security services took advantage of these early signs of dissension within the Brotherhood to ban the long-established organization, informing the Brothers that their bylaws were no longer compatible with the Jordanian Law on Associations.

At that point, two important members, Abdul Majid Thneibat and Rhayyel Gharaibeh, left the Brotherhood to create a rival organization, the Muslim Brothers Association (جمعية الإخوانالمسلمين). Several of the Brotherhood’s offices and financial assets were transferred to the new organization. Although this new association did not trigger a massive shift – it only won three seats at the 2016 general elections – it did strip the Brotherhood and its political arm of part of its power in the national political arena.

In 2015, Zaki Bani Irsheid, the Brotherhood’s deputy comptroller general, was sentenced to 18 months in prison for criticizing the United Arab Emirates. The Jordanian Anti-Terrorism Law, which is frequently wielded against political opponents, was used to justify his highly-publicized arrest. Since it was amended in 2014, the law has categorized as terrorism any action that could ‘harm [Jordan’s] relationship with a foreign country’ (art. 3), while the concept of terrorism has been broadened by the same amendment to cover anything that could ‘disturb the public order’ (art. 2).

Beginning in 2013, political repression went hand in hand with the increased centralization of power. In 2016, a constitutional amendment was adopted, allowing Jordan’s king to appoint various senior state officers, including the president, the members of the Judicial Council, the Army Chief of Staff, the head of intelligence, and the chief of police, as well as the president and members of the Senate, without needing the government’s approval, as was hitherto necessary (art. 40). This strengthening of the king’s powers went relatively unnoticed in Jordan: it was overshadowed by the electoral reform announced the same year – although that reform had been in the pipeline since 2011 – and by the adoption of the Decentralization Law in 2015.

In 2019, repression reached new levels as it was intensified and extended to a broader spectrum of political opponents. Three members of the IAF were arrested between March and December 2019, along with about fifteen activists, including several members of the Bani Hassan, one of the largest Jordanian tribes. More often than not, those arrests were motivated by social media posts (see article in Arabic).

This wave of arrests came in the aftermath of the 2018 protests, which represented an unprecedented time of public opposition to the government and even to the monarchy, especially from the main Jordanian tribes. This large-scale social movement led to the dissolution of the government, followed by a harsher political response with the appointment of Salameh Hamad, known to have little patience for protests, as the new Minister of Interior, and of General Ahmad Husni as head of intelligence. According to the decree of appointment, Husni was required by the king to keep an eye on anyone who dared to go against ‘the foundations of the Jordanian constitution’.

Political parties, the Muslim Brotherhood, and Jordanians of Palestinian origin are no longer the only targets, as criticism of public authorities can now come from any group of the population. In addition to the arrests of activists mentioned before, repression began to affect sectors that had previously gone relatively unscathed, namely the media and trade unions. A Jordanian journalist describes the intimidation she was subjected to:

‘I received a phone call from intelligence services after I posted on Facebook about the tax law [a tax reform that led to a wave of protests in June 2018]. They asked me to come to their offices, I went there alone, I was really scared (…) They asked me to write a new Facebook post that was more positive about the tax law.’

On top of the traditional psychological pressure exerted by security services, some journalists working for foreign or national publications were also beaten and arrested by police during the teachers’ protests, the media coverage of which was banned by the authorities.

The teachers’ union, which had been promised a wage increase in October 2019 after a one-month general strike, was instead subjected to violent repression by the authorities, causing the union to shut down in July 2020, just before thousands of its members were arrested in August. Overall, 2020 marked the third stage of a process in which the regime’s authoritarian practices became increasingly widespread and visible. Until then, legal amendments, arrests, and the crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood were carried out with relative discretion – that is, except for Zaki Bani Ersheid’s sentence – and the executive branch had refrained from violently suppressing protests for two decades.

The fact that a trade union had been forced to shut down, especially one that was founded just after the Arab Spring, was also unprecedented in Jordan’s history. The frequent use of gag orders, banning journalists from reporting on certain type of news, has been heavily condemned as well by the media and international organizations, in a country where freedom of speech is guaranteed by the Constitution (art. 15).

Loss of legitimacy and a tarnished image of democracy

The teachers’ protests, which have been ongoing since 2019, have allowed both observers and Jordanian authorities to fully grasp the political clout of professional unions. Recent events highlight the broad legitimacy that they have gained, as well as their capacity to pressure the central state. In October 2019, after more than a month of strikes that paralyzed dozens of schools, and given the public’s support for teachers, who are seen as representatives of the working- and middle-class, the government had to yield to their demands.

However, the importance of those organizations is nothing new: trade unions became alternative venues for protest when martial law was in effect from 1957 to 1991, and when political parties were outlawed.

Teachers were also able to create a convergence of struggles among the opposition to the authorities’ repressive practices. The union embodied resistance to both austerity measures and attempted repression by the state, which no political party had managed to do until then. This remarkable achievement is at least partly due to the ‘de-ideologized’ and non-denominational nature of the union, which allows it, unlike the IAF, to stand up for the interests of the entire population, in spite of the regime’s attempts to portray it as being controlled by the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Brotherhood publicly and repeatedly expressed its support for the union, especially during the August 2020 wave of arrests. Mourad al Adaylah, the Secretary-General of the IAF, also organized several official visits, accompanied by a delegation of the party, to meet the members of the union who had been liberated since the end of the summer.

This unprecedented civil disobedience movement – the last general strike before this one took place in 1989 – took Jordanian authorities by surprise and tarnished the image of a stable country under control. In this unusual context, the government’s decision to dissolve the union in July 2020, immediately after announcing a wage freeze in the public sector, can be more fully understood.

Demonstrations in support of teachers were held all over the country, in spite of the the ban on gatherings of more than twenty people due to the state of public health emergency. Because of this ban, the Court likely had not anticipated such protests, unlike those that took place in 2011 and 2018, which were strictly controlled by the state. The heavy repression that followed was both visible and relatively unprecedented; it seems to have been a deterrence measure meant to assert the government’s stability and authority at the expense of its democratic façade.

Obviously, this strategy entails consequences both inside and outside of Jordan. On August 19th, 2020, the Office of the United Nations High-Commissioner for Human Rights urged Jordan to reverse the decision to close down the teachers’ union, calling it a ‘serious violation of the right of freedom to association’. The crackdown on the demonstrations in support of teachers is also an unheard-of event for Jordanians themselves, who condemn the continued use of public health measures to justify the ban on protests.

The political authorities’ legitimacy has been severely weakened by these events. Earlier large-scale popular uprisings focused on economic grievances, such as purchasing power, but the regime’s repressive practices now seem to have shifted the focus onto its authoritarianism. Consequently, the government’s tight grip undermines the image of democratization that the monarch has tried to project, especially after 2011.

The ruling power has tried to invisibilize, or at least to make amends for, the repression of the past few months by announcing that general elections would be held on November 10th, 2020 after having been postponed due to the Covid-19 epidemic. However, this announcement seems to be producing the opposite of its intended effect. In spite of the efforts made by the independent electoral commission, which was created in the wake of the Arab Spring to encourage citizens to vote and reassure them of the transparency of the electoral process, voter turnout is likely to be at least as low as in previous years.

In 2016, only 37% of registered voters actually cast ballots. The number of votes won by the opposition will be determined by voter turnout, in a climate of harsh repression, and the IAF predicts massive interference by the intelligence services6. The party’s spokesperson made a press statement:

‘Many reasons lead us to boycott the upcoming parliamentary elections. (…) [especially] the context of the elections even before they start, and we have proof (…) of very strong pressure, surpassing anything we have seen in the past (…) Candidates are being pressured not to run in the elections.’ (interview, in Arabic)

Journalists for the left-wing daily newspaper Al-Ghad7 highlighted the apparent contradiction between the holding of general elections and tribal consultations8 and the prohibition of certain trade union elections, such as that of the lawyers’ union, officially due to the coronavirus pandemic. Under the Jordanian system, before every election, the country’s tribes and large families hold ‘internal consultations’ before every election in order to choose the candidate that will represent them. Naturally, they do not always reach a consensus, so several members of a tribe may run concurrently.

Other political parties that had been known so far for their friendly relations with the authorities have spoken out against the upcoming elections, for which both repressive and public health measures will prevent them from organizing election rallies. One member of the National Constitutional Party has voiced his objections to the elections in the media and on social networks. On September 10th, he wrote in a Facebook post: ‘We will not trust you or your elections, because of your inflexibility, your security measures, your promises of freedom and your lies.’

The events that have unfolded over the past few months have led many media and political actors to expose the political system’s democratic façade, despite having previously agreed to play the government’s game while understanding its limits. The election process and its results in November will reveal how effective this questioning of the official discourse actually was.

Conclusion

The events of 2020 uncovered authoritarian practices inconsistent with the image that the Jordanian regime wants to cultivate outside its borders. With the successive reforms implemented since the 1990s, the authorities were determined to defend a record that was almost a rarity for international donors: political stability, economic prosperity, and democratic pluralism. But behind this discourse, a discreetly coercive system was maintained, invisibilizing both social demands and their repression by the authorities.

Beginning in 2011, the growing number of protests was accompanied by intensified repression, which became more visible than ever in 2020. The past few months seem to have marked the end of an enchanted interlude for Jordan in the wake of the Arab Spring. As with the Moroccan monarchy prior to the Rif movement in 2016, the Kingdom of Jordan managed to maintain the appearance of addressing social protests without violence and without undermining its political legitimacy.

That illusion is now gone, as protests and criticisms are mounting in all sectors of Jordanian society (tribes, political parties, trade unions, the media, etc.), forcing the authorities to broaden and publicly reveal their repressive practices. Beyond the consequences for the national political scene, this unmasking could have repercussions for Jordan’s relations with its foreign partners, including states, international organizations, and development agencies, which are key to the economic performance of the ruling power.

Notes

- While protesters in Egypt and Tunisia asked for the fall of the regime, demonstrators in Jordan wanted to reform it (الإصلاح). ↩︎

- The number of victims is disputed, especially because the Palestinian ‘issue’ is a very sensitive one in Jordan at the moment. The lower estimates establish the death toll at 3 500. ↩︎

- The term ‘Transjordanians’ refers to Jordanians whose families lived on the territory before 1948, whereas the Jordanians of Palestinian origin mainly arrived after the 1948 and 1967 exoduses. In Arabic, they are called ‘East Jordanians’ (شرق أردنيين ). ↩︎

- During the 2007 municipal and legislative elections, the political opposition spoke out against election fraud. See for instance the interview with former president of Parliament Abdal-Latif Arabiyat (1990-1993), also a member of the Islamic Action Front. ↩︎

- See the report by the Foundation for Strategic Research (2017), ‘The Muslim Brotherhood Movement: from Pillar of Monarchy to Enemy of the State’ ↩︎

- The party finally decided to run for elections. ↩︎

- Founded in 2004, first private daily newspaper in Jordan. It is considered as the main paper that is relatively critical of political authorities, especially after various investigations on social issues. Their criticism is tolerated and integrated to the political system, as was illustrated by the recent appointment of former editor-in-chief Jumana Ghuneimat as Minister for Media Affairs and government spokesperson in 2018. ↩︎

- Before every election, tribes and clans hold ‘internal consultations’ in order to choose the candidate that will represent them. Naturally, they do not always reach a consensus, so several members of a tribe may run concurrently. ↩︎