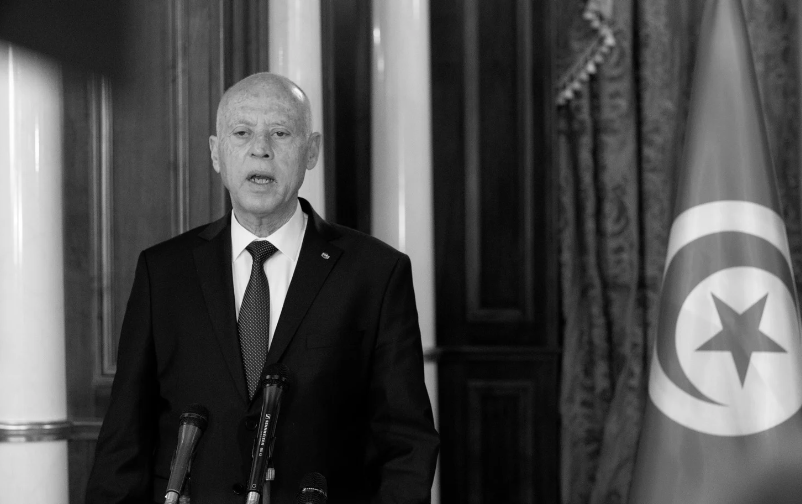

This report from the Noria Research MENA Program offers a consideration of the political moment in Tunisia. It begins by probing the character and prospects of the autocracy which has consolidated around the person of Kais Saied since 2021. From there, it proceeds to evaluate the possibility of democracy’s restoration.

Research findings are many. By way of fieldwork and historical and comparative analysis, we determine that the autocracy of Kais Saied is unconventional in two significant ways. Firstly, it exhibits indifference to both performance and ideology-based legitimacy. Secondly, it foregoes meaningful attempts at “organizing certainty”: Straying from the autocratic mold, the Saied regime devotes few resources to building institutions for rationalizing the management of intra-elite disputes, co-opting and disciplining potential rivals, gathering information on the public, or tethering different social groups to the state. In view of these unconventional properties and of the regime’s weak performance across three domains critical to the longevity of rightwing populists—principally, mass organizing, stewarding a growth coalition, and deploying targeted welfare—the report’s author posits that Saied’s staying power, having grown increasingly reliant upon repression, may be limited.

While that sounds an optimistic note, research findings also suggest that the likelihood of a revived democracy in the short to medium-term is slim. This prognostication is informed by the public’s resentment of political parties and distrust of representative institutions. These facts of contemporary political life—the causes of which are traced to historical processes specific and non-specific to Tunisia—lowers democracy’s chances in two ways: (i) They reduce the probability that popular forces will galvanize behind an opposition movement hitherto steered by the transition’s leading partisans and (ii) In the eventuality that Saied is dislodged, they make the consolidation of democratic rule exceedingly difficult to execute.

The report concludes with a brief discussion of policy recommendations for the international community. As the author makes plain, neither condemning nor opposing Kais Saied will be sufficient to return Tunisia to democracy. Rather, steps must also be taken to address the conditions which make the building of strong relations between political parties and social groups—without which a healthy democracy cannot exist—possible. Critical here are debt relief and other measures to extend the economic policy space.