This text is the conclusion of the Violence Takes Place Series.

The Series has been coordinated by Jayson Maurice Porter and Alexander Aviña.

“You say the government will help us, teacher? Do you know the government?”

Ultima Thule: the northernmost part of the habitable ancient world

Juan Rulfo, Luvina. The Burning Plains and Other Stories, 1967.

Here Comes the Government

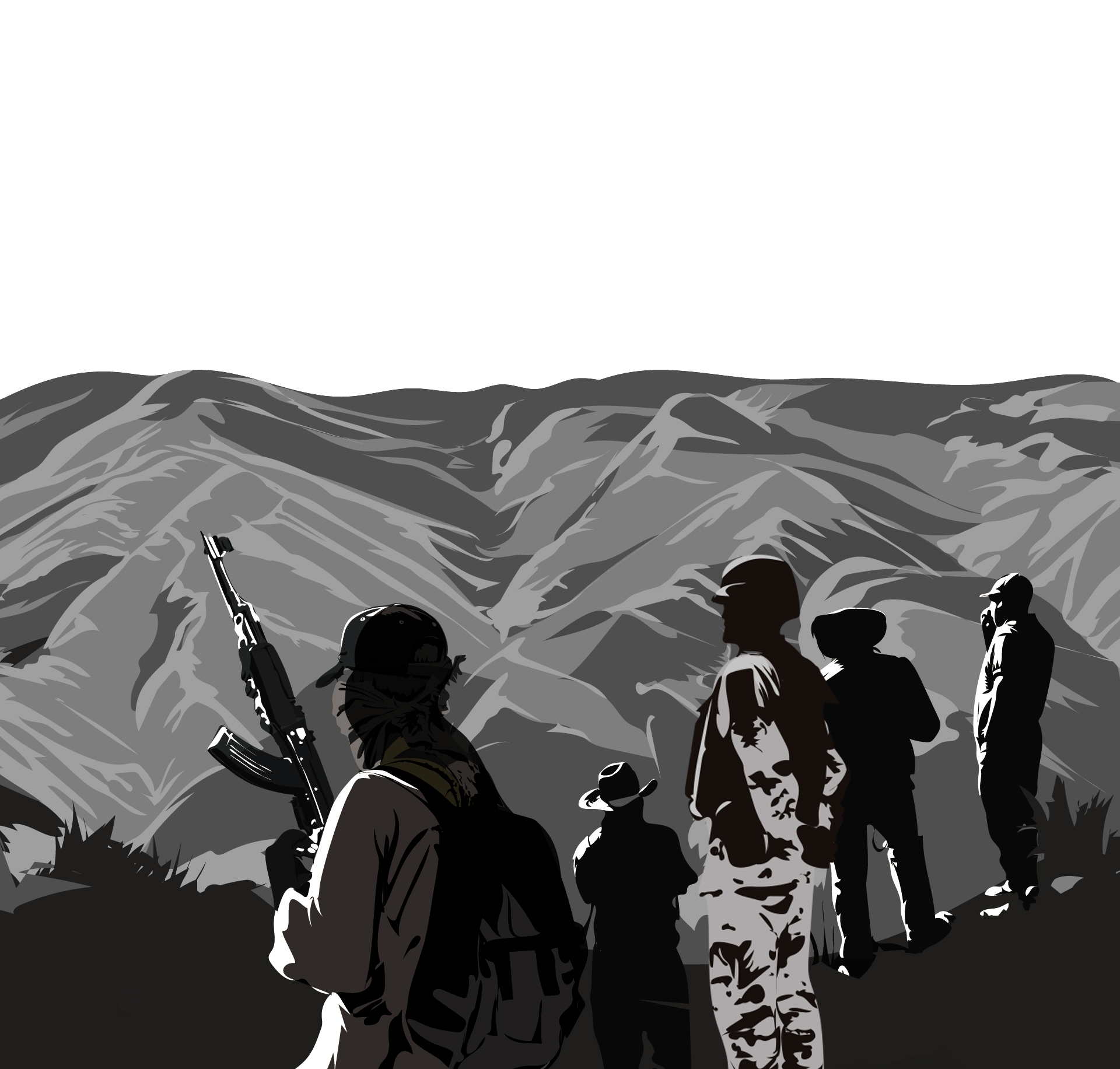

Ahí viene el gobierno. Here comes the government. Back in 2005-2007 when I conducted field research in coastal Guerrero and visited family in the Michoacán hotlands (Tierra Caliente), I often heard this expression prompted by the increasingly common sight of military soldiers and vehicle convoys. It reminded me of Juan Rulfo, the great Mexican storyteller who decades ago chronicled rural life in the decades after the 1910 revolution.

What does this expression mean? What does it mean that some people in coastal Guerrero and the Michoacán hotlands identify the Mexican state mainly through its security forces? That the state is imagined as something mobile and foreign, characterized by a lack of permanence and armed to the teeth? That when the state palpably “appears,” most recently in the form of federal police and military purportedly waging a war on drugs and criminal organizations, violence actually increases?

In a way, this expression provides local insight into the political, cultural and economic geography of Mexico today, particularly the vast conceptual distance that still exists between city and countryside, provincia and capital, northern Mexico and southern Mexico. After two revolutions (1810 and 1910), one compromised independence (1821), several foreign invasions and multiple internal rebellions and civil wars, this colonial spatial imaginary has proven remarkably robust. For example, in his 1971 writing on the Michoacán tierra caliente, historian Luis González y González described the region as alternating between ultima Thule and the world’s buttocks; a place where local inhabitants spotted “dead terracalenteños condemned to purgatory returning home to retrieve a blanket.1These terracalenteños are straight out of Rulfo’s stories, from Luvina, from Comala, from the burning plains.

Going local, and historically and ethnographically contextualizing violence embedded within specific social contexts complicates the dominant narratives that reduce violence to the externalities of drug trafficking in regions where the state is supposedly “absent.”

The contributing authors to the Noria Violence Takes Place Series highlight these communities and regional insights to raise broader implications for understanding contemporary dynamics of violence in rural Mexico. Going to the local and historically and ethnographically contextualizing violence embedded within specific social contexts complicates the dominant binary narratives that reduce violence to the externalities of drug trafficking in regions where the state is supposedly “absent.”

They push us to expand our historical horizons prior to 2006 and to think about how local histories of land tenure, agrarian reform, and political authoritarianism after the 1910 Revolution “set the table”—to borrow a metaphor from contributors Cecilia Farfán-Méndez and Jayson Porter—for the gradual emergence of an illicit drug economy. The focus on land, markets and capitalism also requires the expansion of geographic horizons to understand how the creation of export-oriented commercial agriculture in regions like Sinaloa and Michoacán subjected rural communities to both national and transnational pressures—pressures later replicated by the global narcotics industry and expanded to other localities.

This series is, in a word, about power and its history in the Mexican countryside.

Beyond State Absence or Presence

As ethnographer Irene Álvarez cogently argues in the series introduction, “in various rural areas of Mexico the rupture between a supposedly ‘governable’ country and one plagued with criminal violence does not make sense.”2 How political elites today imagine the border between “governable” and “violently ungovernable” has a long postcolonial history rooted in, most especially, past moments and processes of political struggle that defined who ruled the country—and, crucially, how they ruled.3 Imagining certain regions as ultima Thule, as González does, has historically shaped both epic and more subtle forms of Mexican state-making.

What are the stakes? Perceptions and knowledge production have influenced how different state-forms since independence—from Agustín de Iturbide’s short-lived monarchy to the post-1982 neoliberal state—interface with communities and individuals living in regions imagined as faraway frontiers. The capacity for self-governance, democracy even, hinged on the conceptual location of these racialized frontiers in the political cartography of elites. For politicians and intellectuals in the immediate decades after independence, that cartography contained borders that divided “civilization” from “barbarism,” elite governance from racial caste warfare. Dictators like Santa Anna and Porfirio Díaz resorted to colonialist and Positivist scripts to argue that “childlike” Indigenous, rural, and poor people remained unready for the responsibility of democracy and self-governance.

For politicians and intellectuals in the immediate decades after independence, that cartography contained borders that divided “civilization” from “barbarism,” elite governance from racial caste warfare.

During the 1910 Revolution, Mexico City newspapers described the southern peasant movement as driven by “a barbaric socialism,” led by the “southern Attila” Emiliano Zapata “preaching an apocalyptic doctrine of disintegration and extermination.”4 Decades later in 1960 during a civic rebellion against a brutal governor in Guerrero, an agent from the Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS) analyzed guerrerenses as innately “volatile;” their character “climatologically conditioned;” and their “predisposition for agitation caused by a lack of communication networks and culture.”5Luis González offered an almost identical explanation in his earlier cited 1971 article for the Michoacán hotlands.

To imagine a locality or region as an innately bronco or “backwoods” served to justify certain modes of governance and state intervention—particularly a militarized, heavy-handed approach that looks more like low intensity warfare than democratic governance.6 More coercion, less consensus; “much police, little politics.”7

Presuming state absence in places like highland Guerrero and Sinaloa has led to dirty wars and state terror—under the guise of wars on crime and illicit drugs—since the 1960s. The brutal counterinsurgencies waged against the peasant guerrilla movements led by schoolteachers Genaro Vázquez and Lucio Cabañas in 1970s Guerrero, replicated in “counter-narcotics” form in the northwestern “Golden Triangle” during Operation Condor in the late 1970s, sought to project state power and authority.8

Political scientist Richard Craig argued as much when he questioned the actual purpose of Operation Condor: “could the real motive be to ‘depistolize’ the campo, to prevent today’s Pedro Chávez from becoming tomorrow’s Lucio Cabaña?”9 A military veteran of the anti-guerrilla campaigns in Guerrero during the 1970s termed it differently, “the moment when the people of Atoyac saw and heard the tanks, warplanes and helicopters is when they finally felt that the government was truly powerful.”10

Presuming state absence in places like highland Guerrero and Sinaloa has led to dirty wars and state terror—under the guise of wars on crime and illicit drugs—since the 1960s.

Yet, as the contributors to this series collectively demonstrate, the question is not about the absence or presence of the Mexican state in regions imagined as ungovernable hinterlands. Rather, the question is about what sort of state practices, institutions, and agents exist on the ground in the past and present, and how they become embedded in local constellations of social, political and economic power.

To trace and investigate this power, the contributors especially emphasized matters of land tenure and markets. They demonstrate how struggles to define the parameters and purpose of both—involving local communities, local/regional powerholders, landed elites, and national political elites—shaped the ground from which illicit narcotics production would gradually emerge as a transnational industry by the 1960s and 70s. The violent failure of postrevolutionary agrarian reform and the development of state-supported commercial agribusiness at the expense of ejidatarios created the conditions for narcotics production: a “modernized” agricultural infrastructure (dams, irrigation, roads, credit, etc.) tapped into fickle international markets subject to boom-and bust-cycles, and pauperized campesinos who at times turned to growing illicit narcotics as a way to make ends meet.

The question is not about the absence or presence of the Mexican state in regions imagined as ungovernable hinterlands. Rather, the question is about what sort of state practices, institutions, and agents exist on the ground

Using an interdisciplinary approach, the authors thus—to quote from the work that inspired the series title—show “how social relations take on their full force and meaning when they are enacted physically in actual places.”11 To reiterate: in actual places where history takes place, not in the ultima Thules imagined in Mexico City newsrooms, the Netflix “binge factory,” television news production studios, the Centro Nacional de Inteligencia (CNI), or the National Palace.12

Be it in the countryside or the supermarket, geography and politics historically reproduce power, which is rooted in and derives from local and global conflicts over land and markets. Though the story varies by rural region, the late journalist Javier Valdez Cárdenas’ contention that Sinaloa’s drug trafficking organizations trace their origin to the violent rollback of land reform in the 1930s necessarily reframes current discussions on organized crime by providing historical context and structure.13In this series, the drug problem is a consequence of how capitalism and political power functioned in the countryside.

In this series, the drug problem is a consequence of how capitalism and political power functioned – and still functions – in the Mexican countryside.

Drugs, War, and Capitalism

The research and analysis start locally in the places where violence actually takes place in order to understand ongoing dynamics in coastal Guerrero and the highlands in Nayarit, Sinaloa, Oaxaca and Michoacán. And once they arrive, investigate local archives, ask questions, and listen, these scholars help reorient the lens of analysis to ask: what can the contemporary Luvinas teach us about the dynamics of violence in Mexico today? How can violence taking place at the local lead national and international dialogues and policy conversations on issues like narco-trafficking, forced displacement, and structural violence (or environmental degradation)—issues that represent symptoms of deeper historical maladies?

Such an approach leads the contributors to collectively suggest that the failure to ask such deeper questions will only produce limited analysis and superficial solutions to the question of violence and the drug trade in Mexico today.

The failure to ask deeper questions about power will only produce limited analysis and superficial solutions to the question of violence and the drug trade in Mexico today.

This series also interrogates the multiple forms of violence that historically and currently shape everyday life in these localities. The articles reveal how subjective forms of violence occur in top-down fashion (e.g. landed elites versus landless campesinos) that reflect class hierarchies/economic power. As discussed by Curry, the impact of avocado cultivation in Michoacán has resulted in highly unequal economic gains “leading to transformed communities replete with social tensions”.14 Violence also takes place horizontally within marginalized communities and homes—especially gendered violence as Jayson Porter discussed with the various writers and scholars he interviewed for the related podcast series.15

As a guerrerense schoolmaster told Álvarez, “there had always been quarrels over land, women or alcohol.”16 Nathaniel Morris’ article on Náayari indigenous communities in the Nayarit highlands reveals the internal conflicts and class stratification that result as a consequence of the drug trade. Violence from the outside can also serve a generative function. As Gabriel Tamariz argues in his article on milperos in Oaxaca, a communally-organized and controlled drug trade has helped reinforce community solidarity—a similar though uneven process also uncovered by Morris.

Yet, the various contributors never lose sight of the “slow” violence, the structural violence, the violence—to paraphrase Argentine Liberation Theologian José Míguez-Bonino—that is constitutive of the worlds in which everyday life takes place.17

Journalist and sociologist Dawn Paley terms it “drug war capitalism,” a contemporary model of globalized capital accumulation that manifests itself in places like Guerrero, Michoacán, Sinaloa and Nayarit as the violent dispossession of communal resources like land, water, forests, human life itself—though not without engendering popular resistance.18

“Drug War Capitalism”: a war waged against poor people, in which the Mexican state, far from being absent, actively participates.

This war is one waged against poor people in which the Mexican state, far from being absent, actively participates. Indeed, as the work of Benjamin Smith and Romain Le Cour Grandmaison demonstrate, since at least 1940 it has fomented violence, using it as a “political resource” to negotiate authority and ruling configurations in the countryside, rationalize licit and illicit markets, and even engage in the extortion of criminal organizations.(In Smith’s study of the Mexican drug trade, the state acts like a protection racket: “state agents were Mexico’s mafia, trading protection for a cut of narcotics proceeds.”)19 State formation on the cheap, reliant on local partners and/or the sending in of police and military forces—as Violence Takes Place strongly suggests—tended to exacerbate violence and marginalization at the local level.

Conclusion

Violent Takes Place represents much-needed deeper academic studies and political conversations. The stakes in these conversations are enormous for a country that has suffered nearly 500,000 homicides and almost 100,000 enforced disappearances since 2006.

A state that distrusts local communities and fails to protect journalists and environmentalists. The histories, theorizing and experiences learned from localities disrupt and potentially undermine perverse and cartel-obsessed paradigms generally used to explain violence in Mexico today. Normative ahistorical “security” paradigms that assume state absence, capture, or failure in the countryside where the “good” state agents battle the “evil” cartels, prioritize mano dura militarized responses at worst, and police/prison/judicial reforms at best. Balazos remain the immediate “catchall solutions to social problems”while the abrazos— deeper structural reforms that speak to decades of unresolved and intensified rural inequality—are relegated to a distant future (if ever at all).20

The war on impoverished peoples in the Mexican countryside continues. “I told them it was their country,” the teacher in Rulfo’s short story said. “They shook their heads saying no. And they laughed. It was the only time I saw the people of Luvina laugh. They grinned with their toothless mouths and told me no, that the government didn’t have a mother.”

Ahí viene el gobierno. Here comes the government.

Notes

- Luis González y González, “Tierra Caliente,” Extremos de México: Homenaje a don Daniel Cosio Villegas (Mexico: Colegio de México, 1971), 116. Ultima Thule, in ancient Greek and Roman cartography, referred to the most distant of lands, those places on the map beyond known borders. ↩︎

- Irene Álvarez, “Rurality, Drug Trafficking, and Violence: A Model to Assemble,” Violence Takes Place, Noria Mexico and Central America Program (September 2020) – Link. ↩︎

- A classic example from nineteenth century Latin American history is Argentine intellectual and politician Domingo Sarmiento’s use of the civilization-barbarism dichotomy to demarcate what he proposed as the ideal future of this country: the growth of “civilized” cities made more so by European immigrants superseding the “barbaric” gaucho countryside as a relic of the past destined to disappear. Domingo Sarmiento, Facundo: Or, Civilization and Barbarism (New York: Penguin Classics, 1998 [1845]). ↩︎

- Gilly, The Mexican Revolution, 82-83. ↩︎

- Archivo General de la Nación (AGN), DFS 100-10-1, Legajo 7, ff. 90, 92-93. ↩︎

- Alan Knight, “Cárdenas and Echeverría: Two ‘Populist’ Presidents Compared,” in Amelia Kiddle and María L.O. Muñoz, eds., Populism in 20th Century Mexico: The Presidencies of Lázaro Cárdenas and Luis Echeverría (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2010), 22. ↩︎

- Journalist Juan Angulo quoted in Julia Preston and Samuel Dillon, Opening Mexico: The Making of a Democracy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004), 281. ↩︎

- The Golden Triangle refers to the highland region where the states of Sinaloa, Durango, and Chihuahua intersect (and, historically, the main site of marijuana and heroin production in Mexico). Adela Cedillo, “Operation Condor, the War on Drugs, and Counterinsurgency in the Golden Triangle (1977-1988),” Working Paper 443, Kellogg Institute for International Studies (University of Notre Dame, 2021). ↩︎

- Richard Craig, “Human Rights and Mexico’s Antidrug Campaign,” Social Science Quarterly 60:4 (1980), 698. ↩︎

- El Edén Bajo el Fusíl, dirs. Salvador Díaz and Pedro Reygadas (1982). ↩︎

- George Lipsitz, How Racism Takes Place (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 3. ↩︎

- Josef Adalian, “Inside the Netflix Binge Factory,” Vulture (10 June 2018). ↩︎

- Javier Valdez Cárdenas, The Taken: True Stories of the Sinaloa Drug War (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017), quoted in Cecilia Farfán-Mendez and Jayson Maurice Porter, “Setting the Table: The Licit Beginnings of the Sinaloa’s Illicit Export Economy,” Violence Takes Place, Noria Mexico and Central America Program (December 2020). Link. ↩︎

- Alexander Curry, Violence and Avocado Capitalism in Michoacán, Mexico. Link. ↩︎

- “Conversations on Gender, Geography and Violence Against Women in Mexico and Central America,” Noria Mexico and Central America Program. Link. ↩︎

- Álvarez, “Rurality, Drug Trafficking.” ↩︎

- See Shannon O’Lear, ed., A Research Agenda for Geographies of Slow Violence: Making Social and Environmental Injustice Visible (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2001). And José Miguez-Bonino, quoted in Stephen C. Rose, The Development Apocalypse or Will International Injustice Kill the Ecumenical Movement? (World Council of Churches, 1967), 108. ↩︎

- See, for example, the actions of Canadian mining companies since at least 2000. Dawn Paley, Drug War Capitalism (Oakland, AK Press, 2014), 101-102, 151-161; and Claudio Garibay, et al., “Unequal Partners, Unequal Exchange: Goldcorp, the Mexican State, and Campesino Dispossession at the Peñasquito Mine,” Journal of Latin American Geography 10:2 (2011), pp. 153-176. ↩︎

- Romain Le Cour Grandmasion, “Michoacán es un cuarto oscuro,” Nexos (16 September 2019); Benjamin T. Smith, The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade (New York, W.W. Norton, 2021). ↩︎

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 2. ↩︎