This article is Chapter 5 of Noria MXAC “Violence Takes Place” Editorial Series.

“Growing milpa is a profoundly political act of resistance.”

Alberto Cortés, El maíz en tiempos de guerra

Negotiating Violence in the Cultivation of Marijuana & Poppy

In the years 2018 and 2019 I systematically visited four state prisons in Oaxaca, where I spoke to hundreds of prisoners. After the morning roll call, I would approach and talk to them in the courtyard or during the group talks that I organized on peasant vulnerability and the legalization of drugs. I interviewed seventy-six prisoners in order to discuss a delicate subject well known by them but not easily tackled: the marijuana and opium poppy in their hometowns.1

For farmers and their families, milpa has been key from various angles to reduce the risks of anti-narcotic coercion. Thereby, with some exceptions, it has not been substituted or displaced; on the contrary, it has been strategically conserved.

I found shared voices and experiences despite the great socio-ecological diversity in the state of Oaxaca. In this essay, I specifically analyze the relationship between milpa and the violence that is related to the criminalization of marijuana and poppy cultivation. The milpa is a family polyculture that is mainly grown for self-consumption. It is centered on maize but involves other domesticated species (usually beans and squash) and semi-domesticated edible plants (many of them known as quelites). For farmers and their families, milpa has been key from various angles to reduce the risks of anti-narcotic coercion. Thereby, with some exceptions, it has not been substituted or displaced; on the contrary, it has been strategically conserved. In a context of high production of illegal crops, the conservation of this agrarian system has fostered community organization for effective negotiations with soldiers and drug trafficking organizations.

As I will argue here, these prison testimonies confirm milpa as a community political institution, and they reflect the relevance of this ancestral polyculture in the analysis of violence in illegal crop production zones in Mesoamerica, which is milpa’s center of origin and diversity.

Agrarian Historical Context

Thousands of years before the arrival of marijuana and poppy to Oaxaca, the ancestor of maize and today’s wild relative (teocinte) had already been domesticated in this same region. The oldest vestige of this domestication in the whole world discovered to date was actually found in Oaxaca, in the Central Valleys. These remains are about 6,250 years old.2

Since then, humans, maize and other food and medicinal species have together migrated and created settlements in all of the micro-regions in the state. Their coevolution is nowadays evident in linguistic and maize diversities, which are very closely related.3 Fifteen indigenous languages (and their variants) are spoken and 35 varieties of maize are cultivated in Oaxaca as part of the milpa system.4 In the last decade, 250 thousand families planted 540 thousand hectares of rainfed maize, which is almost completely native varieties.5

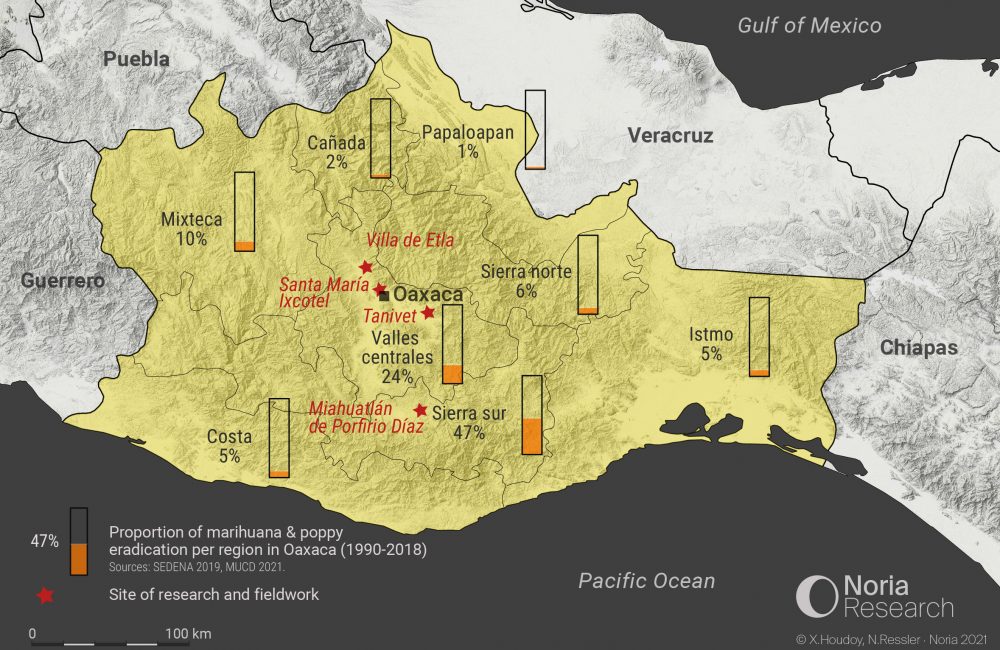

From 1990 to 2018, the destruction of these crops by the Mexican army was focused mainly in the Southern Highlands, but it involved 78% of the municipalities in all eight regions of Oaxaca.

In contrast, marijuana and poppy first arrived to a few Oaxacan towns in the 1960s. Their production expanded considerably in the following decades. From 1990 to 2018, the destruction of these crops by the Mexican army was focused mainly in the Southern Highlands, but it involved 78% of the municipalities in all eight regions of Oaxaca.6

It has been almost entirely milperos (milpa growers) and their families who voluntarily and independently grow marijuana and poppy in Oaxaca. Forced labor by drug trafficking organizations is practically non-existent. I know of only one municipality where farmers were forced to grow these crops. In other municipalities there have actually been failed attempts of such imposition by these organizations, who have been repelled by the armed resistance of the community, including curfews, armed confrontations and lynching. But beyond these sporadic episodes, what is worth emphasizing here is that illegal crop production is principally carried out by smallholder units and does not involve coercion for the monopolization of production.

It is also noteworthy that in Oaxaca there are no immigrant laborers in the production of illegal crops, unlike others regions in Mexico and South America. Land is used and managed almost exclusively by locals, which is a right that has been historically anchored in common property, a tenure encompassing approximately 75% of the land in the state.7

A Strategic Coexistence

Given the possibility of growing and selling marijuana and poppy and therefore increasing the family income, milperos are faced with a common dilemma in agriculture. They have the option of specializing in a single crop for reasons of efficiency, marketability, and profitability, or alternatively can integrate this commercial crop to their production system and this way diversify risks. Specialization in fact offers major profits but, from one moment to another, everything can be lost. Being without of both food crops and money to buy food is definitely the worst-case scenario.

Beyond sporadic episodes, it is worth emphasizing that illegal crop production is principally carried out by smallholder units and does not involve coercion for the monopolization of production.

Risks include crop theft, which is always latent and more common than with legal crops because of their superior commercial value. In order to avoid theft, one or more men in charge remain armed in the field, or close by, a few weeks before and during the harvest.

Secondly, some producers intercrop marijuana or poppy with maize in the same field, but this camouflage is not common. To start with, not all the varieties of maize are tall enough to cover the marijuana. Besides, when intercropping they compete for sunlight and soil nutrients. And if this were not enough, soldiers evenly slash and fumigate without caring if maize is destroyed. Maize, marijuana and poppy get along better when not grown together.

On the other hand, the decision taken by farmers to abandon milpa can cause suspicions among neighbors willing to denounce them because of previous personal or family conflicts, or simply out of envy. “If (s)he doesn’t grow milpa”, they would say, “what does (s)he do for a living?” Therefore, while growing marijuana or poppy far away, many will concurrently but separately grow milpa in their usual (close by) fields, even if only to avoid such suspicion.

Maize and the other domesticated and semi-domesticated species in the milpa system offer the household a food insurance in the face of the vicissitudes caused by the prohibition.

Producers face thieves and denouncers, but also the possibility that soldiers find and destroy the field or that crop prices collapse from one year to another. The majority of producers thus prefer to diversify risk; that is, they prefer to conserve their milpa. Families tend to diversify their economy, cultivating for self-consumption and sale, working simultaneously in agricultural and non-agricultural activities in the town, and/or sending one or two members of the family to work up north.

Above all, maize and the other domesticated and semi-domesticated species in the milpa system offer the household a food insurance in the face of the vicissitudes caused by the prohibition. Meanwhile, marijuana and poppy offer not only a monetary income, albeit uncertain, but also the possibility of conserving a peasant livelihood, avoiding emigration as much as possible, and hence conserving the production and consumption of milpa, in a complementary cycle.

Negotiating with Soldiers

At the household level, the diversification of the production system with milpa and illegal crops clearly works as a risk management strategy. The implications of this diversification at community level, however, are much less evident.

In the highlands of Oaxaca, the agrarian system is not transformed but, instead, reaffirmed when illegal crops are incorporated. As I pointed out before, it is a combined system made of small and independent family units, centered on milpa, that operate principally on common property lands. The conservation of this system in municipalities of high marijuana and poppy production is due to the benefits of diversification, the historical social and emotional value of growing milpa, and the predominance of common property because it inhibits any tendency for land accumulation and its associated labor exploitation.

In some municipalities, the assembly has determined to collectively bribe soldiers so that they notify their arrival beforehand and to minimize crop destruction.

The ability of a household to increase its production and profits is thus restricted. However, the resultant similarity of conditions, profits, and risks between households entails common interests. As a consequence, local institutions have been used for collective risk management. Their community assembly is outstanding. For example, in some cases the assembly has determined to grow illegal crops far from town, so as to not expose other people. Community members also summon the assembly to stop crop theft. In some municipalities, the assembly has determined to collectively bribe soldiers so that they notify their arrival beforehand and to minimize crop destruction.

Certain municipality banned confrontations with soldiers. In others this restriction was not necessary because soldiers are strategically treated well; communities members even sometimes fed soldiers and drink with them. The diplomatic sensitivity of organized milperos has also included playing soccer and basketball with them In some occasions, diplomacy convinced soldiers to pretend to walk up hill but camp out nearby and do not destroy any crops. “We send them a cow or a calf”, mentioned an interviewee.

Negotiating with Drug Traffickers

When most milperos produce marijuana or poppy in town, they often purchase guns and high caliber arms. The main purpose of buying high caliber arms is to dissuade crop theft. “No one will take you seriously if you simply have a 22 [caliber rifle].”

Middlemen or harvest gatherers are the ones usually selling these arms or exchanging them for marijuana buds or opium gum. These men are natives of the municipality and buy all or part of the production and afterwards resell it to the carrier on site or at the following traffic link. There are also outsiders who arrive with the sole purpose of selling firearms. They expose them openly “as if they were selling fruit; and they offer good prices too.”

Several milperos with whom I spoke considered that there was a relationship between increased murders and the arrival of these arms. However, further in their description it became clear that these murders were rather related to a social disintegration prior to the marijuana and poppy boom. More weapons alone do not increase violence or incite previously existent conflicts. These towns have been armed with machetes, hunting shotguns and rifles for a long time and have an ancient history of rebellions and conflicts over lands.

Drug-trafficking organizations carry out the regional and international transportation of marijuana and heroin produced in Oaxaca.

They also locally control the cocaine and methamphetamine markets. Milperos seldom interact with members of these organizations.

But the recently acquired high-caliber weaponry has also been key to stopping extortion attempts by drug trafficking organizations. These organizations carry out the regional and international transportation of marijuana and heroin produced in Oaxaca. They also locally control the cocaine and methamphetamine markets. Milperos seldom interact with members of these organizations, as they deal solely with middlemen when trading their illegal crops. If anything, direct contact happens through armed confrontations when traffickers intend to charge taxes or control local production.

Traffickers unsuccessfully tried to enter and take control of two municipalities, but as soon as rumors were unleashed or suspicious people were identified, the purchase of arms intensified and a meeting is called to organize the traffickers’ expulsion.

Given the resistance, which has acquired reputation, one certain drug trafficking organization has held a rather prudent position. In order to guarantee the constant acquisition of a great volume of harvest, the regional person in charge of this organization came to an agreement with the municipality authorities regarding the rent of lands for these crops to be worked by local farmers. Traffickers would also buy the remaining production from the middlemen. From time to time, the traffickers gave town authorities gifts, thus securing the collaboration. “A dove came by and left an egg,” the authorities explained to their people the origin of the money.

I interviewed a member of this organization, the son and nephew of marijuana producing milperos. He himself had been a producer and middleman before becoming a carrier. Referring to a municipality where his organization rented lands, I asked him about forced labor:8

Question: You couldn’t threaten a farmer there, or could you?

Answer: No, because [that town] is very united. People there are murderers.

Q: You wouldn’t mess with farmers?

A: No, not at all. Why? Because maybe we could kill about 15 or 20, but we surely weren’t going to get out of there [alive].

A milpero’s version was just as blunt:9

“There in [my town] no way was there going to be a dude saying: ‘I’m going to lay out my rules, your crops will be mine from now on.’ How dare he, if I’ve been working at this since I was a kid, and you come here and want to take over? No way (…). And that’s what my grandparents always taught us. No one is going to humiliate you. No one. If you are somebody you’re going to do it and you aren’t going to back down.”

Conclusion

The milpa, as faithfully reflected in these prison testimonies, is essential at the household level for risk management and as food insurance, but it also transcends the family realm for its leading role at the community level in the highlands of Oaxaca.

Given the violence associated to the militarized prohibition of growing marijuana and poppy, this agrarian system constituted by multiple independent and small scale units has been a part and served as amalgam of local institutions of mutual aid and collaboration. Among these institutions, land common property and the community assembly have been particularly relevant for collective action facing the “eradication” of these crops and the relationship with drug trafficking organizations.

As described in this essay, milpa and illegal crops mutually benefit in a complementary cycle that offers peasant families a source of monetary income that reduces outmigration, and the uncertainty of food insecurity. The persistence of this system at the community level avoids production monopolies and labor exploitation and therefore permits cooperation among farmers that share common conditions, risks and interests. This includes the shared notion that self-government depends, to a large extent, on an organized and high-caliber local militia.

This case of Oaxaca suggests that in certain illegal cultivation zones in Mesoamerica, the cradle of milpa, the dynamics of violence are partly mitigated in the interaction between this food and agricultural system, community organization and local sovereignty. Growing milpa means building community.

Notes

- Tamariz, G. 2020. Agrobiodiversity conservation with illegal-drug crops: An approach from the prisons in Oaxaca, Mexico. Geoforum. ↩︎

- Piperno D.R., Flannery K.V., 2001. The earliest archaeological maize (Zea mays L.) from highland Mexico: new accelerator mass spectrometry dates and their implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 2101–3. ↩︎

- Orozco-Ramirez, Q., Ross-Ibarra, J., Santacruz-Varela, A., Brush, S., 2016. Maize diversity associated with social origin and environmental variation in Southern Mexico. Heredity 116, 477–484. ↩︎

- Aragón-Cuevas, F., Taba, S., Hernández, J.M., Figueroa, J.D., Serrano, V., 2006. Actualización de la información sobre los maíces criollos de Oaxaca. INIFAP, Informe final SNIB-CONABIO proyecto No. CS002 México D. F. ↩︎

- Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP), Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural (SADER), México. Producción agrícola, estadísticas anuales. ↩︎

- Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional (SEDENA), 2019. Plantíos y hectáreas de marihuana y amapola destruidos por la SEDENA en 1990–2018, por municipio y año. ↩︎

- López-Bárcenas, F., 2009. La diversidad mutilada: los derechos de los pueblos indígenas en el estado de Oaxaca. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), México. ↩︎

- Interview in the state prison in Miahuatlán de Porfirio Díaz, July 2019. ↩︎

- Interview in state prison in Ixcotel, Oaxaca de Juárez, January 2019. ↩︎