Introduction

In Mexico elections and violence were for much of the twentieth century taken as inherently intertwined. As polling days approached press, chattering classes and intelligence routinely weighed up the probabilities of bloodshed during voting and after vote counts. They often erred on the side of caution, and for long stretches observers ended up surprised by what their (admittedly low) expectations deemed tranquility.1

This essay considers the types of violence that actually appeared, during both the electoral process and its aftermath, and how the frequency and intensity of violence changed across the twentieth century, in a tripartite chronology: the gunman’s democracy (1910 to 1952), the “directed democracy” (1953 to 1994), and the dejected democracy (1994 to the present). All, it should be noted, had democratic qualities; all also needed adjectives.2

The Gunman’s Democracy (1910 to 1952)

In the first period, stretching from the civil wars of the revolution until the 1950s, the odds-on bets on voting leading to violence were empirically justified. The revolution was catalysed, after all, by the repression of Francisco Madero’s 1910 presidential run, the first mass, modern campaign – train, telegraph and newspapers were all vital tools, helping compensate for a certain charisma deficit – in Mexican history. Its armed phase ended in 1920 when another presidential candidacy, that of Álvaro Obregón, was curtailed by the Primer Jefe de la Revolución, Venustiano Carranza; Carranza as a result was himself terminally curtailed in the mountains east of Mexico City. His assassination in a one-room shack at Tlaxcalantongo allowed Obregón to construct the first of the twentieth century’s broad political churches and to bring the five-year “war of the winners” to an end, reconciling unviable guerrilla armies with a stalemated would-be-state.

Yet here endeth not the lesson, because the church of the revolution was fundamentally schismatic. The presidential election campaign of 1924 led to the rebellion of over half the army, led by the excluded Adolfo de la Huerta (Obregón, according to legend, told his fellow northerner that he was overqualified to be president, whereas Plutarco Elías Calles was so incompetent that he would end up homeless without the presidency.) Generals, some more sincere in their democratic ideals than others, launched rebellions in anticipation of the rigged presidential elections of 1928 and 1929. The presidential election of 1928 led to the assassination of Obregón himself, shot dead in a café by a wandering cartoonist.

Most electoral violence was not hidden at all, and political memoirs read like pulp fiction.

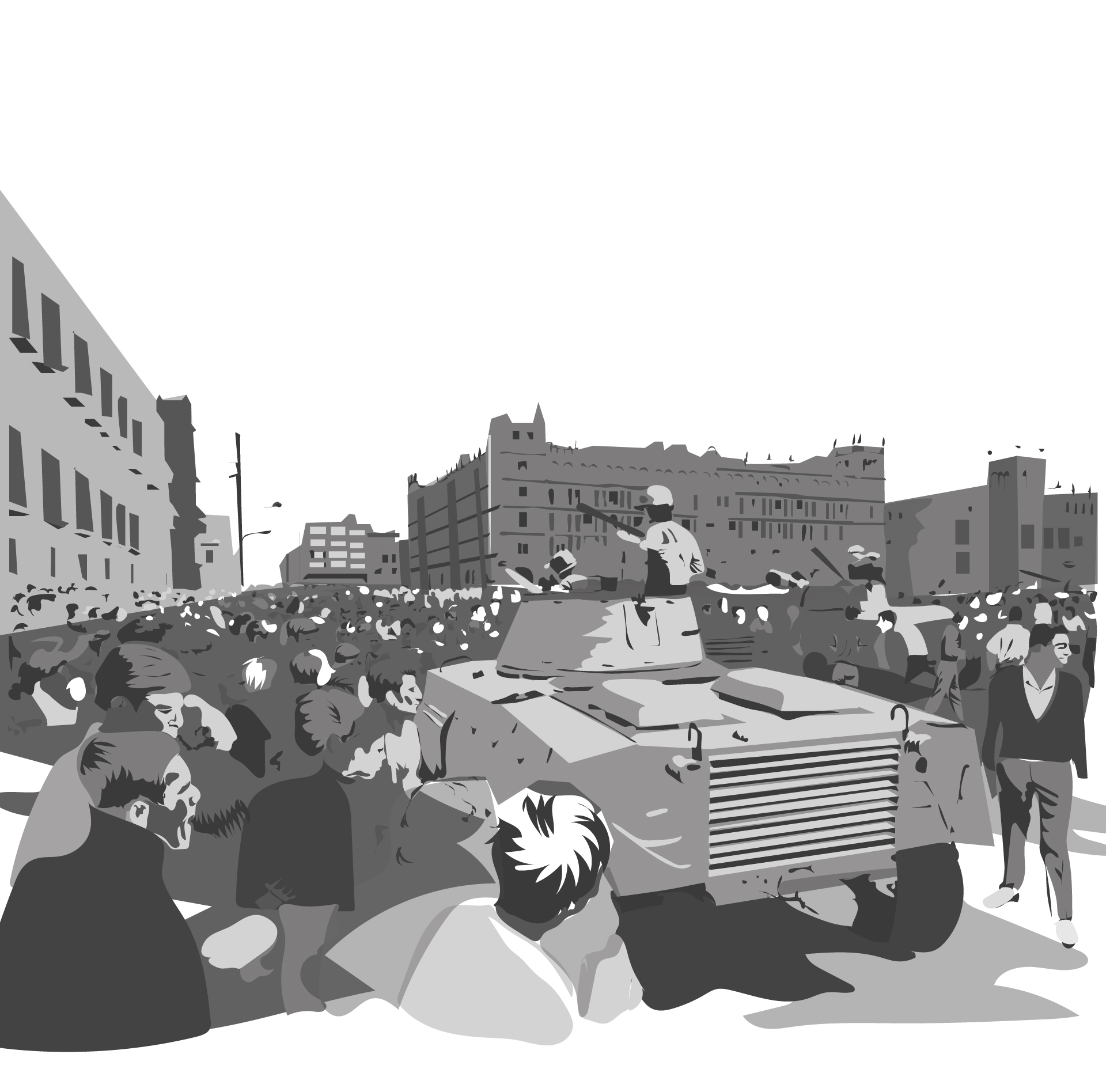

The Partido Nacional Revolucionario’s choice for his replacement, Pascual Ortiz Rubio, was shot in the head (but survived until the 1960s) after election day heavies killed at least nineteen in Mexico City.3 The 1934 election of Lázaro Cárdenas, roughly peaceful, was an outlier; in 1940 streetfighting left tens dead in Mexico City, while in 1952 mounted police and mechanized infantry killed and wounded numerousdemonstrators in the Alameda, arresting five hundred more.4 Even the 1946 election, depicted as the first shoots of a peaceful democratic spring, was to some extent violent, celebrated by a rebellion in the north of Guerrero, hidden, half-hearted but real, and an intelligence flap when the exiled loser was reported to be heading with a small convoy from San Francisco towards the border.5

Yet most electoral violence was not hidden at all, and political memoirs read like pulp fiction. José Vasconcelos, a candidate in 1928, was told – by the US ambassador, with Tarantino-esque relish – that he was not presidential material because he was no good at shooting people.6 At the other extreme Gonzalo N. Santos, congressman, governor and quotable hard man, wrote of shoot-outs in Congress – “the chamber still smelt of gun smoke” – or in the unlikely environs of las Lomas de Chapultepec, where he machine-gunned opposition voters on election day in 1940, and of his subsequent rush to hose blood out of a polling booth before escorting the outgoing President Cárdenas there to vote (Cárdenas, with typical poker face, observed how clean it was).7 Politicians who looked like cowboys or gamblers packed guns quite automatically, an English traveller observed; Martín Luis Guzmán’s fictional Diputado Axkana González was marked as “indelibly civilian” not because he didn’t carry, but because he carried clumsily, in an ill-fitting hip holster, in a world where elections “aren’t about votes; they’re about saps and pistols, shivs and blades.”8 Foreign journalists wrote sensational stories of bloodshed and disgust, with Robert Capa photos and headlines such as “Mexicans Hold a ‘Free’ Election for Presidente at the Cost of 100 Killed”.9 Voters shared the disgust; they also learnt dissuasion.

The “Directed Democracy” (1953 to 1994)

This is one of the reasons why the vast majority of electoral violence at the top (and particularly in the centre) occurred before 1952: voters rightly stopped believing that they could influence those elections. The armoured cars and mounted police charges and the subsequent dissolution of the losing henriquista party symbolized (and causally contributed to) a clear turning point, an end to serious party competition for the presidency that lasted thirty-five years. The country was “tranquil” in the run up to 1958, observed the US ambassador, a prediction that none of his predecessors would have got away with.10 In this ensuing period of what participants called “directed democracy” (1953-1994) there were none of the presidential assassinations that marked the US in the same period; no JFK, RFK or Reagan-like shootings. Neither was there an equivalent to the Democratic Convention of 1968 in Chicago; protests were confined to the melting away of acarreados, or the stony face of Fidel Velázquez standing alongside a neoliberal president.

Historically, violence was an indicator of democratic instinct and competition.

The students of 1968 were not protesting about political elections. There were continued beatings, jailings, knifings and shootings at elections, but they occurred at the subnational level, becoming more prevalent as voting moved away from the cities and down the political ladder. The elections that Mexicans cared most about and could do most about were for their mayors and their governors, and because of those elections’ intimate importance and ultimate plasticity – if enough voters really cared town halls could be won or lost, governors could be vetoed or fired – violence remained a possibility en provincia across the entire century.

So violence was, counter-intuitively, an indicator of democratic instinct and competition. Anyone could take part, and in controversial elections the crowd – in the French sense of a people up in arms, not acarreados – could be more socially diverse than anything in revolutionary Paris. In Mexican villages or towns there weren’t many conventions or talking shops, and the crowd was often the only game in town.

The main actors in electoral violence, though, were the professionals, the street-fighters, policemen (above all the municipal ones), union thugs, pistoleros and soldiers. Their role was to guarantee the victory of the favored candidate, el bueno, and they worked to do that at four stages of an election: party candidate selection, whether by bloc vote at a convention or by primary election; vote casting on election day; vote tallying shortly thereafter; and inauguration day. They did so by two varieties of violence: the dissuasive, putting off troublesome electors and their candidates by intimidation, beatings, jailings and homicides; and the persuasive, creating the numbers of victory by seizing polling stations, protecting the carrusel, those paid voters who went round and round the polling stations voting again and again, and stealing boxes that promised too many opposition ballots.

The main actors in electoral violence were the professionals, the street-fighters, policemen (above all the municipal ones), union thugs, pistoleros and soldiers. Their role was to guarantee the victory of the favored candidate.

Electoral violence was not merely repressive, though, and at times dissident voters of the crowd fought back. This could happen at any stage of the election, but it was at its most effective in the patterned riots of inauguration day, when crudely armed demonstrators would gather, storm the town hall and install their own candidate as mayor. There were several outcomes to such collective bargaining by riot. The governor could sustain the results, at the risk of further violence and the unwelcome attention of Mexico City. He might nullify the results and install either a compromise candidate, or, more rarely, just hand the election over to the opposition.

In the last analysis some handed the problem over to the army, installing a petty military dictatorship. The first course was risky, courting the political fatality of a massacre or even a rebellion: Rubén Jaramillo, Genaro Vázquez and Lucio Cabañas all took to the sierra when they lost elections. The second was a sign of weakness that might encourage others to riot down the line. And the third was undoable after the demilitarization of the 1940s. All viable choices, in short, were bad ones.

Caught between a rock and a hard place, the executives of the mature PRI developed a more sensitive approach to candidate selection, taking auscultación – jargon for taking the voters’ pulse – more carefully before engaging in orientación, jargon for directing constituents whom to elect.

At the same time they also ended primary elections, sharply reducing the institutional paths to political competition. While caciques persisted, governors were fired for mismanaging violence and their successors learnt to forestall it. In 1946-1947 two governors (Guanajuato and Chiapas) were fired on grounds of post-election riot and massacre; after that the governors who lost their jobs did so through ineptitude, student protests, economic stupidity and general dislike, but never for straightforward election violence.11 With the new delicacy came a sharp decline in reactive militancy (very few town halls were stormed over the next forty years) and a new class of mayor; not necessarily all that representative – unionized workers were almost wholly cut out of ayuntamientos, and the new men tended to the bourgeois – but a lot less controversial than their predecessors.12

While electoral violence never wholly went away, with exceptions such as the navista campaigns in San Luis Potosí it decreased and moved largely out of sight, confined to the more remote places and the brief time when the PRI reinstigated primaries in the 1960s. Political instability on a national scale came back in the 1980s, as the PRI entered terminal decline and electoral competition grew. Part of the new dangers lay in intimidation and unmaterialized threat, whether in the gubernatorial contests of the 1980s, the failing bulwark against the opposition flood, or the rumours of army restiveness, or the presidential contest of 1988, when De la Madrid had Presidential Guards ready in the basement of the National Palace, or the election of 2000, when Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas called Vicente Fox a traidor a la patria immediately before voting.

There was also a new violence, though, a rewind towards the gunman’s democracy: the widespread killings of local opposition candidates, the return to town hall stormings, and finally the cupular assassinations, first of presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio and then of the party’s secretary-general, José Ruiz Massieu. In the end, though, the only nationally salient electoral violence was cyberwarfare, if that even counts as violence, the sabotage in the 1988 presidential election of new computers that were counting far too many opposition votes for comfort. The most important sorts of violence of all, an autogolpe or straightforward golpe, the assassination of an incumbent president or a proper national rebellion, never materialized, and in 2000 the PRI lost the presidency.

Conclusion – The Dejected Democracy (1994 to the present)

The arrival of democracy, or at least the final downfall of the PRI-in-power, was always going to bring some dejection. If you remember the night in the Zócalo when Cárdenas won the Distrito Federal, the tens of thousands celebrating, a parrot on one Prdísta shoulder chanting “one, two, three / chinga su madre el PRI”; or in 2000 the French ambassador asking how he could not be happy, France has won the European Cup and the PRI has lost the election; or later the same day, or rather the next morning, 2 am at the Angel de la Independencia, a beaming, sweaty Vicente Fox repeating “ahora festejamos, mañana trabajamos“; remember any of that from the here and now and dejection follows. But there is more to disillusion than the disappointments of the shift from campaigning to governing.

The next presidential election in 2006 brought Felipe Calderón to power and a million AMLO supporters to occupy downtown Mexico City. Calderón’s immediate declaration of the war on drugs was a scoundrel’s ploy aimed at distraction and khaki legitimacy. There was no raison d’État to justify the militarization of the Mexican countryside; a comparative increase in domestic drug use had still left the country with one of the lower rates of consumption in the world. Calderón’s decision started a war that has left more Mexicans dead or displaced than the Cristiada. In that criminal ultraviolence (and the copious everyday political violence it cloaks) electoral violence in the strict sense is a drop in the bucket.

If, on the other hand, contemporary violence is seen as stemming from that razor-thin victory, which caused a president’s morally corrupt, reckless choice of an unnecessary and unwinnable war, then all contemporary violence is, at a long stretch, electoral. And a sort of Mexican ostalgia13 for the bad old days of the “directed” democracy with its jailings, beatings, riots and killings wholly, and tragically, comprehensible.

Click here to discover the Elections & Violence in Mexico Project.

Click here to go back to the Mexico and Central America Program.

Notes

- “Two Dead, Ten are Hurt After Mexican Election: Only Clash of Day”, noted the New York Herald Tribune in 1928, while their verdict on the slaughterous 1940 election was that “The rioting and bloodshed attending the Mexican Presidential election on Sunday were less than might have been expected”. New York Herald Tribune July 8 1928, July 9 1940. A US journalist in Chihuahua in 1986 complained that his editors were demanding “articles on the violence. But what the hell can I do? There isn’t any.” Vanessa Freije, Citizens of Scandal: Journalism, Secrecy, and the Politics of Reckoning in Mexico (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 183. ↩︎

- The description “gunman’s democracy” is that of Gonzalo N. Santos, in his Memorias (México DF, 1984), 255-256; “directed democracy” was standard-issue PRIspeak; the idea of the Mexican political system as a “democracy with adjectives” is to be found in Enrique Krauze’s essay, “Por una democracia sin adjetivos”, Vuelta, January 1984. ↩︎

- John W.F. Dulles, Yesterday in Mexico: A Chronicle of the Revolution, 1919-1936 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1961), 475. ↩︎

- Carlos Martínez Assad, El Henriquismo, una piedra en el camino (México DF, 1984), 58-60. ↩︎

- Gurrola to Gobernación, 16 November 1946, AGN/DGIPS-792/2-1/46/425; Gobernación to SEDENA, 27 November 1946, AGN/DGIPS-793/2-1/46/428; Baig Serra to Gobernación, 27 November 1946, AGN/DGIPS-792/2-1/46/425. ↩︎

- José Vasconcelos, “El Proconsulado” in Obras Completas (4 vols., México DF, 1957), vol. ii, 80. ↩︎

- Santos, Memorias, 460-461, 720. ↩︎

- Robert H.K. Marrett, An Eye-Witness of Mexico (London, 1939), 9; Martín Luis Guzmán, Obras Completas vI (México DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1984), 502, 1056. ↩︎

- Life, July 22 1940. ↩︎

- Quoted in Eric Zolov, The Last Good Neighbor: Mexico in the Global Sixties (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 21. ↩︎

- Carlos Moncada, ¡Cayeron! 67 gobernadores derrocados (1929-1979) (México, 1979), 390-392. ↩︎

- Benjamin T. Smith, “Who Governed? Grassroots Politics in Mexico under the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, 1958-1970,” Past and Present 225:1 (November 2014). ↩︎

- The term refers to post Cold War nostalgia in some communist countries. ↩︎