Interview with Alejandro Velasco, conducted by Fabrice Andréani

How would you characterize the U.S. policy towards Venezuela over the last four years?

From the very start, Donald Trump administration’s Venezuela policy heralded its rather singular approach not only to foreign affairs, but to politics more broadly. Despite waging a four-years-long aggressive “maximum pressure” campaign against Nicolás Maduro’s government, the President and his team lacked a cohesive strategy with clear guidelines echoing well-defined national interests. Rather, it was a more of a disjointed, discontinuous and often contradictory policy, strongly driven by specific – and regularly competing – personal interests of officials in charge.

This campaign saw the imposition of a series of major financial and trade sanctions on the Venezuelan State which were supposed to pave the way for a hypothetical “regime-change”. At the same time, Trump and his collaborators adopted an ever-more threatening communication, regularly informing Maduro that “all options are on the table”. But sanctions ended up striking the population far more than the regime, only aggravating an already extremely severe humanitarian situation, while Bolivarian leaders quickly understood that threats of U.S. military intervention were hardly credible.

In fact, with all his boisterous rhetoric, Trump’s interest in Venezuela was always less about “regime-change” than about winning Florida’s all-important Electoral College votes in 2020, as he was seeking a second term in office. So he basically spent very much time stoking decades-long anti-leftist fear among Latin American expatriate communities, especially Cubans in Miami. That helps explain why, early in his tenure, Trump outsourced his Latin America policy to Florida Senator Marco Rubio. Himself of Cuban descent, Rubio’s own interest in the region lay in reversing Barack Obama’s diplomacy of rapprochement with Havana. In his view, ousting Maduro and installing a US backed regime in Caracas would essentially be a way to break the Cuban government’s primary lifeline – that is, discounted Venezuelan oil.

While American senior officials were also pushing to strangle Maduro’s regime and see it collapse, in each case Venezuela was a means to different ends, not an end in itself. Starting with foreign policy “hawks” Mike Pompeo and John Bolton, who respectively became Secretary of State and National Security Advisor in 2018: both shared a warlike rhetoric, but Pompeo was well aware that both the State Department and the CIA (he had just headed) broadly opposed any military adventure in Venezuela, just as the Pentagon did; whereas Bolton clearly thought that a successful operation against Maduro would convince a skeptical Trump of the desirability or feasibility of waging war with Iran – an obsession he’d been advocating at the White House ever since G.W. Bush’s first term in office (2001-2004).

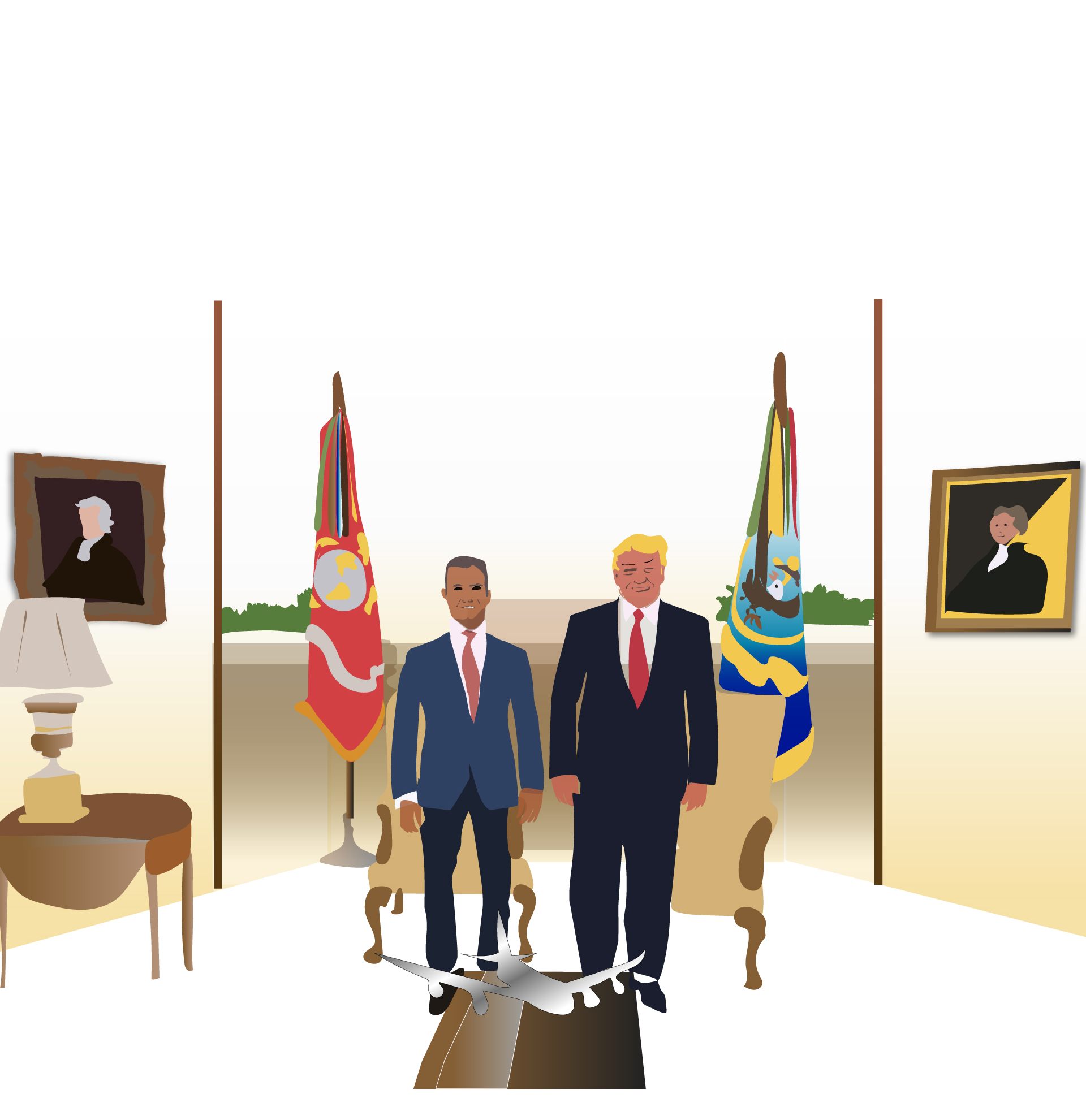

By 2019, Trump gave more credit to that broad interventionist line. He decided to show full support to young Venezuelan representative Juan Guaidó, elected “interim president” by the opposition’s parliamentary majority – and calling on the army to join – as a reaction to Maduro’s widely flawed reelection in 2018.[mfn]Voters overwhelmingly boycotted the process, as the regime refused to update long-outdated electoral rolls (despite the continuous exodus) and banned prominent opposition parties and leaders from participating.[/mfn] Simultaneously, Elliott Abrams, a neoconservative who made his marks along with Bolton throughout Ronald Reagan’s administrations (1981-1988), was appointed Special Representative for Venezuela. For his part, Vice-president Mike Pence began promoting his evangelical coreligionist Guaidó as a providential figure who would “free” the Venezuelan people – and guarantee his re-election along with Trump’s. However, Bolton was pushed to resign as early as September 2019 – given his lack of results –, and ended up expressing harsh criticism for Trump’s “weakness” on the Venezuelan dossier in his memoirs published nine months later.

In the end, most officials had reasons of their own to believe the assumptions of the most radical sectors of the opposition in exile, who convinced them that Maduro was much weaker than what the basic facts on the ground indicated. So while elsewhere in the world Trump sought to negotiate and break “deals” with various types of repressive regimes that restrict political pluralism – North Korea, Egypt, Russia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia –, his approach to Venezuela seemed to stand out as an exception. But this posture was both poorly informed and inconsistent, and thus most often erratic and counterproductive.

To what extent did this policy differ from that of former president Barack Obama, and what conclusions can we draw from it today?

The Obama administration’s strategy sought to combine, as the saying goes, both “sticks and carrots”: on the one hand, targeted sanctions against regime officials suspected of corruption, drug trafficking or human rights violations, freezing their assets in the U.S. and denying them visas to enter American soil; on the other hand, clearly stated conditions for reducing sanctions. In 2016, given the government’s crackdown on the opposition’s newly elected parliamentary majority,[mfn]Ever since 2016, Maduro has continuously governed through the state of exception, nullifying both legislative and executive implications of the opposition’s landslide victory in the 2015 parliamentary elections, and even suspending a mid-term popular recall referendum against his presidency.[/mfn] the organization of free and fair elections, where Venezuelans themselves could decide their political future, became a primary condition for sanctions relief.

By contrast, the Trump administration’s sanctions were all “sticks” and no “carrot”. That approach was based on the belief that Maduro was politically weak, and could easily be ousted by cutting of the state’s main sources of revenue, at least in U.S. dollars. Trump’s economic strangulation policy, first announced in August 2017 – after a four-months-long and heavily repressed protest –[mfn]Ending with the installation of a “plenipotentiary” Constituent Assembly after a fully regime-designed voting process that was boycotted by an overwhelming majority of registered voters.[/mfn] started by forbidding Wall Street from acquiring new Venezuelan debt obligations. Then came the embargo on Venezuelan oil exports to the U.S., along with the freezing of the Venezuelan State’s assets in America and some of its allies (2019); assets included Citgo, the subsidiary of the national oil company PDVSA which runs an extensive refinery and distribution network in the U.S.

“This policy strengthened Maduro’s and his cronies’ grip over the bulk of Venezuelans”

The effects of such sanctions ended up spreading throughout the entire population, especially once PDVSA’s U.S. partners felt short of federal exemptions to continue to operate in Venezuela, and after Caracas was banned from importing American gasoline and diesel (2020). This whole policy proved to be completely counterproductive, as it strengthened Maduro’s and his cronies’ grip over the bulk of Venezuelans. Households without regular access to foreign currencies such as dollars or euros grew ever-more dependent on the increasingly meager resources – especially food – controlled by the government. On top of that, after several years denying the very existence of an economic crisis, Maduro could now point to sanctions as the sole reason for the government’s shortcomings and marshal renewed support both at home and abroad.

Additionally, when the U.S. recognized Guaidó’s “interim presidency” in January 2019, some fifty states throughout Latin America and Europe followed suit. But then again, this diplomatic isolation strategy had the opposite effect: Maduro held on power by rallying support from the military as well as international allies like Cuba, Russia, China, Iran, but also Turkey. As the expectations Guaidó had generated for a quick change began to evaporate, he was thrown into increasingly erratic tactical choices. In April 2019, he staged an ultimately aborted military-judicial coup, with most of his alleged co-conspirators within the regime never showing up. A few months later, he supported the planning of a maritime invasion by a handful of dissident Venezuelan soldiers and U.S. mercenaries, ending up with a spectaculary botched operation in May 2020.

Such choices undermined the credibility of the “interim president’s” figure at home and abroad – including in Trump’s view – and generated deep fissures within the opposition – while strengthening the reputation of Maduro’s counter-espionage services, along with their Cuban partners’. Moreover, by tying themselves to a short-term strategy, the U.S. and Guaidó were caught in a vicious cycle, needing to apply ever more stringent – and counterproductive – sanctions.

Ultimately, the cruelest irony of the Trump administration’s strategy supporting Guaidó’s “virtual government” – a nickname favored by inner opposition critics – is that it did help spur somewhat of a “regime-change”, just not the kind it may have sought: from a seemingly weak authoritarian regime around 2016-2017, to a relatively consolidated dictatorship, with a much weaker opposition to boot.

Should we expect any change from Joe Biden’s new administration?

Joe Biden has a difficult road ahead when it comes to Venezuela. On the one hand, any strategy that appears to ease the pressure on Caracas and/or Havana will risk further alienating the votes of Cuban and Venezuelan expatriates and exiles ahead of mid-term elections – the very communities that helped the Republican Party keep the state of Florida in 2020.

On the other hand, the failure of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” approach clearly calls for rectification, especially as Venezuela’s crisis has long since become a regional – if not hemispheric – crisis. Millions have fled to neighboring countries, putting pressure on already weak local economies and public services, and generating xenophobic backlashes in Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, and elsewhere. Those pressures have only grown during the Covid-19 pandemic, and they are likely to accentuate as those nations try to recover in the months ahead. Hence beyond ideological discrepancies, Latin American governments will probably redouble efforts to bring the U.S. to a different stance on Venezuela.

The Biden administration may use many different tools in order to overhaul Trump’s failed policy. For sure, as promised during the campaign, it has recently granted Venezuelan exiles a Temporary Protected Status (TPS) through which they may legally settle and work in the U.S. during eighteen months. But additionally, and looking back to some of the Obama administration’s key provisions, Biden can offer Maduro’s regime a series of clear political benchmarks in order to gain financial and commercial sanctions relief.

Similarly, its administration can shift its attention from radical opposition sectors in exile to more moderate ones inside Venezuela, like 2012 and 2013 presidential candidate Henrique Capriles. Such a move might help resume talks hosted by Norway between contending parties and shepherd a realistic electoral solution, including chavismo as a key player – whether embodied by Maduro or not; these negotiations had been repeatedly scuttled by the Trump administration’s constant push for Guaidó to outbid. To be sure, while any change in course concerning Venezuela may be risky for the new administration, nothing would be more perilous and counterproductive than maintaining the current status quo.

How might Maduro try to regain his legitimacy on the regional and global stage?

We should be clear that whatever legitimacy Maduro may hope to gain in the region and beyond is neither democratic nor electoral, but rather political. For the last four years, and especially after Maduro’s highly controversial reelection in 2018, antichavismo joined efforts with the Trump administration to “nerd” the president abroad, make him irrelevant. They constructed and promoted a totally erroneous reality in which his de jure lack of legitimacy is tantamount to a de facto lack of legitimacy. Within this context, what Maduro is basically seeking now is leverage over any eventual negotiation with the so-called “international community”. So his focus will be twofold: cement his control over political forces claiming to represent chavismo, and keep the opposition splintered.

Regarding the first aspect, parliamentary elections on December 6, 2020 were plagued both upstream and downstream by government-driven judicial maneuvers and irregularities not only against antichavismo, but also dissident chavista sectors, including a self-serving modification of the whole voting pattern. The government managed to grab over 90% of Parliament, but at the price of a massive opposition boycott. Maduro was equally enabled to stifle any whiffs of criticism from chavista bases and to reward “madurista” loyalists, in a bid to solidify his control over the state.

Meanwhile, and with respect to the second aspect, the opposition has once again begun to eat itself from within. In fact, even as some quarters in the “international community” continue to show support for Guaidó, the end of the legal term of the former National Assembly (on January 5, 2021) and the departure of his patron from the White House (on January 20) have seriously called into question his ability and legitimacy to represent, much less lead, an ever-more variegated and fragmented opposition.