Though rarely achieving what they set out to, democracy promotion programs are not without political impact. The e-Parliament project in Jordan is instructive in these regards: while it did not shift the balance of power in favor of the institution, it did affect the daily praxes of parliamentarians as well as the ways through which they seek to legitimate themselves before a variety of constituencies.

Introduction

In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the European Union (EU) quickly acknowledged the mixed results of its past action in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa. Articulating something of a mea culpa, an official statement put out in the early days of 2011, for instance, declared that “recent events (…) have shown that EU support to political reforms in neighboring countries has met with limited results” 1. Not content to merely apologize for misdeeds past, the European commissioner at the time Stefan Füle also pledged that going forward, the EU would “bring [its] interests in line with [its] values” 2, especially as concerned democracy.

Ten years on, most observers agree that the EU’s post-2011 pivot was one of style rather than substance. Rhetoric notwithstanding, EU priorities for and interventions in the region continue to be driven by security imperatives and economic interests.

At first glance, Jordan appears to buck this trend. There, as Ann-Kristin and Madeleine Mezagopian document, “the Arab uprisings did motivate the EU to allocate more assistance to political reform”. One output of this assistance was the launch of the EU Support to Jordanian Democratic Institutions and Development (EUJDID)3 program in April 2017. With a budget amounting to 17.6 million euros, the four-year EUJDID program was expressly designed to buoy the democratic reform process that the Royal Court initiated in response to mass protests of 2011. It was structured around four primary objectives: supporting parliament, assisting with elections, supporting political parties and supporting civil society organizations.

The EUJDID in Practice

Operationally central to the EUJDID’s efforts in supporting parliament was an e-Parliament initiative.4“E-Parliament” refers to the integration of information and communication technology (ICT) within parliamentary activities and is generally regarded as a means for making legislatures more open, transparent and accessible for the citizenry.

In its public facing discourse, the EU has claimed that its investments in transforming the House of Representatives into a functioning “e-Parliament” constitutes one of the notable successes of its democracy promotion agenda in Jordan. While not entirely without merit, such claims belie a great deal. Helping make parliament more ICT friendly, after all, has done nothing to impact the deeply authoritarian system within which the parliament operates. In providing a veneer of reform while foregoing any substantive engagement with the underlying realities of power, moreover, it can even be argued that efforts in supporting an e-Parliament function to buttress rather than challenge authoritarianism. Benjamin Schuetze has developed this thesis considerably in his works on international democracy promotion programs. 5

That all said, though the EU’s e-Parliament initiative may have failed to deliver a more accountable and representative democracy in Jordan, that did not render the intervention without effect. To the contrary, the EUJDID initiative can be shown to not only have altered the basic functioning of the House of Representatives itself, but the habitus of elected officials as well.

Jordan’s emergent e-Parliament

The push for an e-Parliament actually came from the Jordanian House of Representatives (HoR) itself.

Well before the EU’s arrival, the HoR’s IT department had been working on digitizing the parliament with an eye toward improving workflow, reducing costs and transforming the Parliament into a paperless environment. Aware of the funding coming available from Europe, the department ultimately managed to secure external financing for their efforts through the EUJDID—despite the terms of that agreement having already been set by representatives from the EU and the Jordanian authorities prior to their solicitations. Critical to their twenty-fifth hour coup was the backing IT department received from the Secretary General of the Parliament at the time, Firas al-Adwan. So too was appeal that communication technologies held in the eyes of the EU delegation, who considered such fixes a simple means for enhancing the transparency of the parliament.

Over the course of four years, the e-Parliament project established new archiving and management systems, a new conference and e-voting system, a new website, and live broadcasting of the parliamentary sessions. It also financed budgets for tablets, which were distributed to all MPs.

The transformation of the HoR into a computerized environment had a myriad of effects. To begin, it facilitated enormous efficiency gains for the parliamentarians themselves. As was recounted by one staffer:

“For the oldest MPs, of course they feel the change, especially for the agenda [of the sessions]. For the previous councils, it was hard copies. In some cases the session agenda was a heavy agenda, more than 200–300 pages. Now they have it in electronic format, we send the agenda to MPs through the iPad. Then, when they come to the council they don’t even have to have their own iPad or print out copies because they already have it on the screen in front of [their seats in the assembly]. So this is a major change. (…) Once the agenda is established, by one click it will be sent to all MPs. Previously we had to call a private company, and they took the hard copies and delivered it to MPs houses. Can you imagine for the one living in Aqaba? They had to take it to the MP in Aqaba 6. It takes time.”

From the constituent’s perspective, elements of the e-Parliament initiative also served to make the HoR more transparent, “open, instant and online”7. New equipment made it possible for parliamentary sessions to be live streamed and shared on social networks: the HoR’s Facebook page 8 would henceforth be filled with publications on the institution’s news, photos of the sessions and meetings of parliamentary committees. The HoR’s official website would also be completely redesigned so to furnish easily accessible information on the deputies and the legislative documents being discussed under the dome.

All transcripts of parliamentary sessions since 1989 can now be found online as well. This new data accessibility represents a significant development for the Jordanian citizens as well as for the researcher in social science.

Transparency as a legitimation strategy

Political openness and transparency are today amongst the items most frequently championed by democratic states and societies. E-Parliament-related initiatives are deeply embedded within such discourses. The Declaration for Parliamentary Openness and Transparency, officially launched in 2012 at the World e-Parliament Conference on the International Day of Democracy, for instance, has posited technological upgrades as essential to the prospects of more transparent and responsive governance. As the general thesis holds, tech-powered transparency allows the constituent to more immediately observe his/her MP’s behavior and decisions. Mindful of future elections, the claim is that this surveillance will incentivize the MP in question to improve their performance and vest the entire system with greater accountability.

In the case of Jordan, the relative youth of its e-Parliament makes it complicated to evaluate the impact of the initiative. At a preliminary level, however, it appears to have had the following positive effect: per parliamentary staff’s perception, e-Parliament has boosted the credibility of the House of Representatives by providing greater documentary evidence of the work the MPs do. In a context where this institution has seen its reputation thoroughly soiled over the course of three decades and is generally perceived as powerless9, videos and records showing MPs actively engaged in the tasks they were elected to carry out can only but have had an affirming effect.10

Every day, the assembly schedule is shared on social networks, including meetings of committees and parliamentary groups. Infographics are also regularly published to show how many bills have been debated and voted on by MPs in recent weeks, or how many questions have been asked of the government. All of this together pictures a rationalized and institutionalized work, and MPs seriously endorsing their role of legislators and oversight with significant room for maneuver in their relationship with the executive authority.

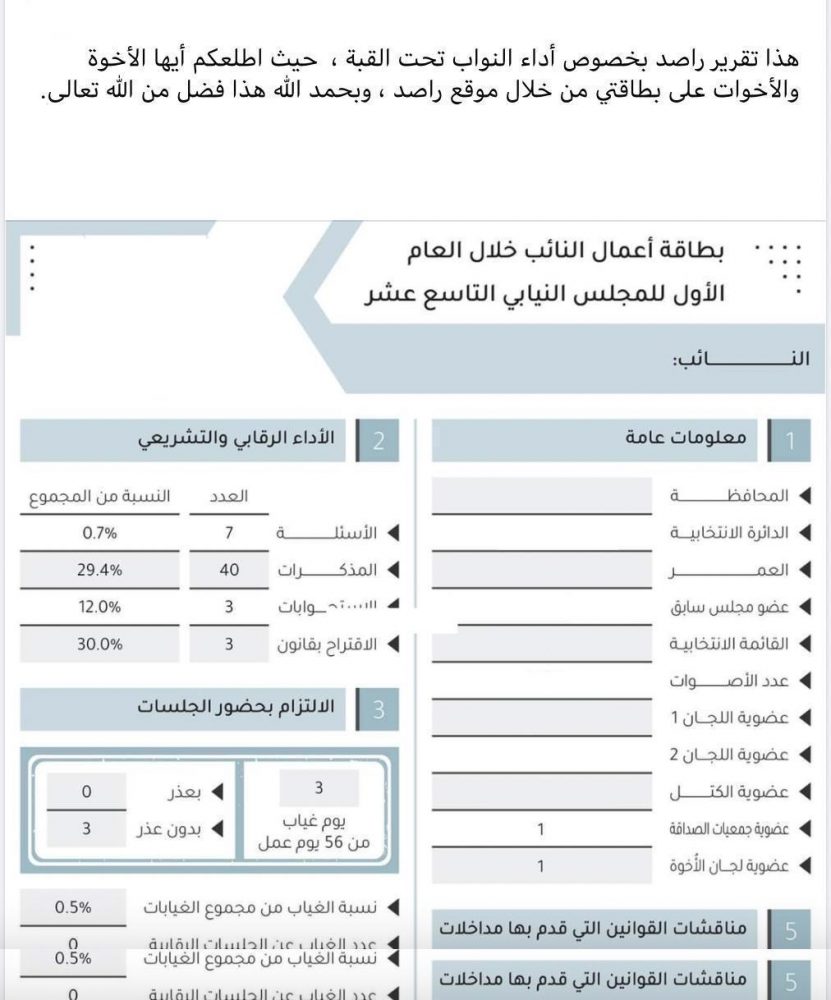

Though it is early days yet, we can also tentatively conclude that the advance of e-Parliament has affected the manner with which Jordanian MPs practice their job. Today, a vast majority of these officials have become very active on social media. Followed by several thousand people, many disseminate the photos and videos shared on the HoR’s pages with considerable frequency. In terms of content, they usually try to highlight their involvement in parliamentary debate sessions or during question-and-answer sessions with the government in order to prove the energy expended in defending the citizens’ interests. Some of them, notably young MPs and the representatives of the Islamic Action Front—the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan—also share the evaluations published by national supervisory bodies like RASED 11, an institution charged with recording and coding parliamentary behavior.

These developments suggest a transformation is underway as pertains to the legitimation strategies used by Jordanian MPs. This transformation was needed by dint of changes afoot in the political system more generally. Elected officials today are granted fewer resources to redistribute to their constituents, partly because of neoliberal policies, such as privatization and public service reforms. Unable to lean on these means for securing public support, it seems plausible that MPs might instead seek to glean legitimacy through the performance and narrativization of classic legislative work.

The limits of transparent authoritarianism: The example of electronic voting

Interestingly and despite latching onto other technological upgrades, Jordan’s parliamentarians have not chosen to use the instrument thought to be at the heart of the EUJDID e-Parliament project: the electronic voting system. Although the HoR changed its bylaw in April 2019 to make the electronic voting the preferred voting modality, Jordanian MPs are today still voting by show of hands, preventing the systematic recording of their voting behaviors.

The pandemic may have had some effect on the non-adoption of e-voting. Since the new system was only installed during the summer of 2019, the suspension of parliamentary activities beginning in March 2020 could have left too little time to train parliamentarians in how to use it. Without ruling this possibility out entirely, it seems unlikely to be at the root of the matter. After all, no progress has been made as concerns e-voting despite a new HoR being elected in November 2020 and despite normal, in-person operations commencing in January 2021.

The reasoning behind the shunning of e-voting is likely to be found in politics, and in the nature of the electoral system in particular. 12 The electoral system in place since 2016, just like the one that had been in force since 1993, incentivizes voters to cast their ballot for candidates with whom they have personal or social ties. Such incentives reinforce the idea that the primary function of elected representatives is to mediate the distribution of patronage by linking constituents to the state through the distribution of jobs, scholarships, medical aid, and the like. All deputies, even those who belong to a political party (12 deputies out of 130) complain about the stubbornness with which voters cling to these ways of thinking. And though the regime makes a point of publicly lamenting the endurance of traditional clientelist expectations and practices, in actuality, it subsidizes their reproduction. Many MPs regularly receive a small amount of money from the Diwan of Royal Court to pass along to their constituents.

And here we come to the matter of e-voting. Access to the Diwan’s resources, after all, comes at a price. Typically, it requires that the MP agrees to respect voting orders passed down from the Royal Court or the intelligence services. This is especially so when it comes to important bills, such as tax laws. As a result and somewhat paradoxically, the imperative of securing resources that can be distributed to constituents will often compel MPs to vote for legislation that is likely to hurt those same constituents. Keen that their complicity in this pain not be exposed, they refuse to use e-voting because they do not want to leave a permanent, public record of their vote behind.

Conclusion

This study of the EU’s e-Parliament initiative in Jordan lends insight into the actually existing effects and externalities of democracy promotion. In ways intended and not, the EUJDID project very much transformed the daily operations of Jordan’s House of Representatives. The installation of new technologies furnished individual MPs with novel means for generating legitimacy. The broader facelift also allowed the HoR itself to better perform its efficiency and modernity for constituents and members of the international community alike.

What the EUJDID project did not do was substantively advance the cause of democracy proper in Jordan. Render the parliament more transparent though these efforts have, they have done nothing to affect a system of governance that ultimately vests the Royal Court and Ministry of Interior with supreme and virtually unchecked authority. In this sense, the project ought chasten those who believe structures of power can be reformed through technocratic fixes alone. Shining a light on the legislature is all good and well, but if that is not where government truly resides, the accountability gains for the citizenry will only ever be marginal.

This article is based on data collected during various fieldwork in Jordan between 2019 and 2021, mainly through interviews with MPs, parliamentary staff and EU civil servants. For safety and privacy reasons, the interviews have been anonymized.

The project relies on a partnership between Noria Research, Sine Qua Non and the French Institute of the Near East (IFPO). It benefitted from the financial and research support of the French Institute of the Near East, a first peer-review by Sine Qua Non and a full edition and peer-review support given by Noria Research.

Bibliography

- Camille Abescat & Simon Mangon (2020), “When repression leaves the shadows in Jordan”, in Noria Research.

- Tanja A. Börzel, Thomas Risse & Assem Dandashly (2015), “The EU, External Actors, and the Arabellions: Much Ado About (Almost) Nothing”, in Journal of European Integration, 37:1, 135-153.

- Ann-Kristin Jonasson & Madeleine Mezagopian (2017), “The EU and Jordan: Aligning Discourse and Practice on Democracy Promotion?”, in European Foreign Affairs Review, 22:4, 551–570.

- Benjamin Schuetze (2018), “Marketing parliament: The constitutive effects of external attempts at parliamentary strengthening in Jordan”, in Cooperation and Conflict, 53:2, 237–258.

- Benjamin Schuetze (2019), Promoting Democracy, Reinforcing Authoritarianism. US and European Policy in Jordan, Cambridge University Press.

Notes

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52011DC0303 ↩︎

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_11_436 ↩︎

- jadîd means new in Arabic ↩︎

- In the EUJDID’s own words, the objective was to “strengthen the functioning of the House of Representatives (HoR) in exercising its core parliamentary functions in a professional, accountable, and transparent manner ↩︎

- Read our interview with Benjamin Schuetze ↩︎

- Aqaba is the most southern Jordanian city, on the Red Sea shores. It takes up to 5 hours to reach Aqaba from the capital. ↩︎

- Internal document: “e-Parliament Systems. 2018 Implementation Roadmap”. ↩︎

- https://www.facebook.com/representativesjo ↩︎

- Indeed, the Jordanian HoR can be dissolved at any time by the King, it can only approve the budget submitted by the government or reduce the planned expenditures, it can propose a law, but the latter must be sent to the government which has the authority to present it or not to the HoR, and it is in practice often bypassed ↩︎

- Interview whith the author ↩︎

- https://www.rasedjo.com/ar ↩︎

- Interview conducted by the author ↩︎