The repression with which the government of Daniel Ortega dismantled the rebellion of April 2018 has produced a growing and seeminly unstoppable exodus from Nicaragua. The vicepresident and wife of the president, Rosario Murillo, continues to claim that Nicaragua is the land of “good living.” However, her words are constantly belied by the facts: by the brazen murders of Indigenous people in the Bosawás reserve, killed by colonists who openly seize their lands in full view of the army; by the victims of state-sponsored paramilitaries; by the citizens who suffer the effects of government negligence in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, whose dangers the government denies, and indeed increased by promoting political marches and mass festivities. Broad macroeconomic figures have so far helped to divert attention from the thousands of households that have gone bust. But one only has to look at the thousands of hotels and restaurants that have closed, the shuttered-up bank branches, the frozen construction projects, and the empty universities to conclude that the dire economic impact is spreading, although unequally, like a shadow across a country whose principal sources of foreign exchange remain highly productive and enjoy good prices on the international markets. Beyond these big numbers, there is fear and there is hunger.

Both fear and hunger have, in turn, driven thousands of Nicaraguans to flee. They have changed country because they have despaired of their country ever changing. They hold onto the rage that, as happened in April 2018, has the potential to overcome their fear; but they have given up hope of any change emanating from the current political leadership. For this reason, the exodus has carried away with it many of the grassroots leaders who led the rebellion and who now apply for asylum in the USA, Costa Rica, Spain and other countries.

The exodus of Nicaraguans has assumed ever-larger proportions over the last three years. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that more than 87,000 Nicaraguans had sought safety in Costa Rica by early 2020, and that a total of more than 103,600 Nicaraguans had been displaced since 2018.1 If a similar percentage of the population of the USA had been displaced, we would be talking about five million people driven into exile.

In only three years.

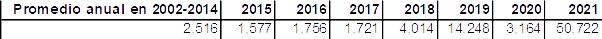

There exists various indicators of the soaring number of Nicaraguans migrating to the United States. Due to the often unauthorised nature of this migration, the available sources can only give us an indirect and approximate idea of its scale, probably far below the reality. According to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (2021), between October 2020 and September 2021 a total of 50,722 Nicaraguans were detained as they tried to enter the country, a number much, much higher than for previous fiscal years (see Table 1).

The number of Nicaraguans entering the US legally has also grown rapidly, going from 3,692 in January to 7,375 in June of 2021 (Cagnassola, 2021). Some of these migrants later become “overstayers”: people who remain in the country despite their legal authorization having expired.

The increase in both authorized and non-authorized immigration has resulted in a greater number of Nicaraguans – usually those claiming asylum – passing through the US migration court system. This phenomenon had already become recognisable several years ago, and is clearly part of a growing tendency. There were 4,145 migration cases involving Nicaraguans in September 2018. This number increased to 12,006 cases in December 2019, a rise of nearly 190 percent and a total surpassed only by asylum claimants from Cuba and Venezuela, according to Trac Immigration (2021).2

The US migration courts in which Nicaraguan asylum cases are heard are able to fast-track and favourably settle these claims if they are consistent with the position adopted by other US government bodies towards the Ortega regime. Congress, the Treasury Department, the State Department and the US Embassy in Nicaragua have all approved santions in response to human rights abuses, have issued statements against corruptiuon and warned US nationals about the arbitrary actions of the Ortega regime and the chaotic situation currently prevailing in Nicaragua. However, every Nicaraguan asylum seeker must defend their claim and prove that, above all, their life is at risk if they are deported back to a country where being a political dissident is a capital crime.

Many of the Nicaraguans seeking asylum in the US have suffered traumatic experiences, but not all of them can provide evidence of such experiences and thus substantiate their claims to be victims of persecution. How can you prove a rape that happened six months ago in a secret underground prison of the Judicial Assistance Department of the National Police? How does one demonstrate beyond doubt that a mob ripped the blue and white shirts you had made from off your back, beat you to a pulp, and then threatened you and your entire family with death? How do you convice a judge that, because you led a literacy campaign in the city of Estelí that was funded by a minor opposition political parfty, your Sandinista neighbours shot you three times and then caved your head in with a metal pole?3

Success in court depends less on the evidence presented than on the persuasive skills of lawyers and expert witnesses, and on the sensitivities of the judges. Sadly such difficulties open the door to discretionality and the unfair loss of cases in which deportation is equivalent to a death sentence.

Nonetheless, the US government does take into consideration the situation from which Nicaraguans are fleeing, allowing an ever-great proportion of them to enter the country while they wait for the resolution of their asylum claims: 20 percent in 2019, 35 percent in 2020 and 45 percent in 2021, according to a report from Trac Immigration (2021a). The majority entered between October 2020 and January 2021, above all through the Brownsville area, on the Gulf Coast border between the US and Mexico and the end point of the shortest and most dangerous of the migration routes connecting Central America with the US. To wait inside the US, rather than in Mexico, increases the chances of being represented in court by a lawyer. As a result, many more Nicaraguans are now successful in their claims for asylum, with an approval rate of 36 percent in 2020, far above the average for all nationalities of 26 percent (and of only 17 percent for Salvadoreans, 13 percent for Guatemalans and 11 percent for Hondurans). Citizens of these other Central American nations exert much more pressure on the US refugee and asylum system because their numbers remain so much greater: a U.S. Customs and Border Protection report (2021a) asserts that between twice and five times as many Salvadoreans, Guatemalans and Hondurans are detained trying to enter the US than Nicaraguans. But migration engenders migration: once the current wave of Nicaraguan migrants have established themselves in the US, they will call out to their families and Nicaragua will join the three nations of Northern Central America as a major source of migrants seeking a new life in the US. There is no telling how long the government of Joe Biden will maintain its relatively forbearing policies towards Nicaraguan migrants, and what other policies might replace them.

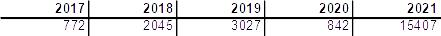

The statistics gathered by the Mexican Immigration authorities (“la migra”), accessible via the website of Mexico’s Interior Ministry (2021), add further weight to the idea that the exodus of Nicaraguans shows no signs of slowing down. A comparison of the figures for the years between 2017 and 2021 shows that the quantity of Nicaraguans detained (or, as they gently put it, ‘presented before the migratory authorities’) in Mexico rose from 772 in 2017, to 15,407 in 2021.

The discontent that has pushed so many Nicaraguans into fleeing their country, however, has paradoxically been transformed into an economic lifeline for those that the exodus has left behind. Albeit often slowly and haphazardly, the rising number of Nicaraguan migrants in the US are sending back home increasing quantities of remittences to help keep their broken household economies afloat, which in turn aids the survival of the system that ejected them in the first place. Migration is thus generating a rising Gross External Product – some 63 percent of which originates in the US – that belies Nicaragua’s financial sovreignty: 1,501 millon dollars in 2018, 1,682 million in 2019, 1,851 million in 2020 and 2,147 million in 2021. In the first quarter of 2022 it already totalled 866.5 millon dollars, maintaining its upward tendency according to the Central Bank of Nicaragua (2021, 2022). And so the vicious cycle is completed: the ejected sustain their ejector.

Notes

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), (2020) ‘Más de 100.000 personas forzadas a huir de Nicaragua tras dos años de crisis política y social’, UNHCR, 10 March 2020. Available at: https://www.acnur.org/noticias/briefing/2020/3/5e67b6564/mas-de-100000-personas-forzadas-a-huir-de-nicaragua-tras-dos-anos-de-crisis.html [last consulted: 20 October 2021]. ↩︎

- Trac Immigration defines itself as an organization dedicated to collating “comprehensive, independent, and nonpartisan information about immigration enforcement.” https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/ ↩︎

- These are the kinds of stories that I gathered during months of research in the field for a book about the repression, entitled Behind the Black-and-Red Curtain: Repression and resistance (Tras el telón rojinegro: represión y resistencia). See https://www.elsotano.com/ebook/tras-el-telon-rojinegro_E1000881592 . My fieldwork generated more than 45 hours of interviews recorded with victims, as well as many more that were never recorded. The stories match up with the declarations of Nicaraguan asylum seekers in the US which I have read as part of my work as an expert witness for lawyers working pro bono on the database of the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies of UC Hastings College of the Law. In the last three years I’ve received an average of two requests a month to write statements and/or testify in the migration courts. ↩︎