Introduction

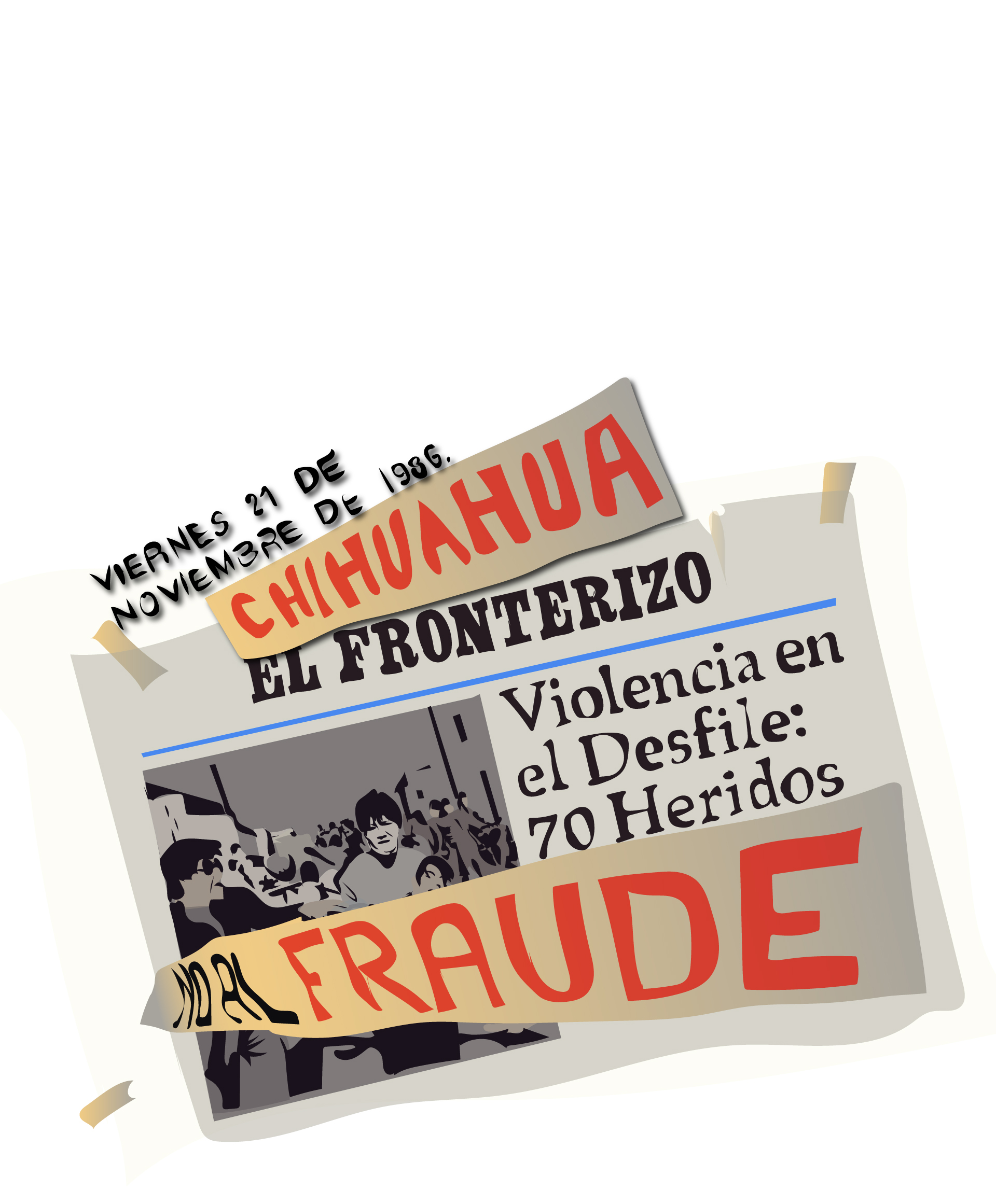

“I had to figure out how to cast 1800 votes [for the PRI] all at once.”1 In a 2011 interview, political operative Joel spoke frankly about his role in fixing the 1986 elections in Chihuahua, a state on Mexico’s northern border. These were highly anticipated contests, with credible forecasts that the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) could lose its first gubernatorial seat ever, auguring the end of one-party rule.

As we talked over the noisy lunch rush at a VIPS chain restaurant, Joel explained the difficulty of stealing or stuffing ballot boxes without being detected or denounced. This became all the more complicated in the 1980s as competitive elections mobilized grassroots movements and attracted national and international media scrutiny.

For nearly four decades it had been an open secret in Mexico that how one voted did not matter; everyone knew that the PRI would inevitably emerge the victor. Yet holding an election was a necessary rite to legitimate the winners.2 Election years were marked by bonanzas of advertising and mobilization. City streets and surrounding hillsides were decorated with posters and painted propaganda; political ads ran constantly on the radio; and state-sponsored rallies filled city plazas. On election day, party organizations bussed in voters with promises of tacos or bags of cement.

For nearly four decades it had been an open secret in Mexico that how one voted did not matter; everyone knew that the PRI would inevitably emerge the victor. Yet holding an election was a necessary rite to legitimate the winners.

But in the 1976 presidential election, high voter abstention and the embarrassing lack of an opposition candidate prompted the PRI to allow for greater competition. Electoral rites only worked if people turned out to the polls. And so in 1977 Congress passed a series of reforms that made it possible for leftist parties to register and compete for the first time since the PRI had consolidated its power. The legislative package also created 100 congressional seats to be allocated by proportional representation, providing opportunities for small parties to win seats without a plurality of votes.

The reforms went into effect as the country entered a severe debt crisis. Unemployment and inflation soared, and Mexico’s ruling party began to face serious challenges. In 1983, the conservative Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) swept the midterm elections in Chihuahua, winning the state’s seven most important mayoralties. Two years later, the conservative party took five out of ten federal congressional seats in contention. By 1986, the PAN stood poised to win the governorship of Chihuahua.

In a desperate attempt to control the process of democratization, the PRI used fraud and violence to win elections, even when doing so became a source of delegitimation. As scholars have shown, the delicate balance of violence and accommodation was central to the PRI’s consolidation of power and its longevity.3 Since midcentury, the party brooked some dissent while selectively repressing other dissidents, most often peasants, Indigenous peoples, urban leftists, and workers seeking to organize independent unions. The surgical application of repression and intimidation remained a party strategy even as elections became more competitive, national media more critical, and civil society more mobilized in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.

Fraud, Intimidation and Physical Attacks

To staunch electoral challengers, Joel, along with many others, had been dispatched to Chihuahua. He began working for PRI in the 1980s and traveled across the country to monitor, and often manipulate, the elections. We first crossed paths when I was doing research in a Mexico City library. Joel spent his days there, and when he learned that I was researching the contested 1986 Chihuahua elections, his eyes lit up. “I worked on that campaign!,” and then added, “You should interview me.”

Joel emphasized the hard work of fraud. He had to spend eight months living in Ciudad Juárez to prepare for the 1986 elections. He and his team aimed to identify sympathetic individuals whom they could buy off and appoint as presidents to manage key polling stations. It was slow, painstaking work to avoid detection. They were in hostile PAN territory with the opposition party in the mayor’s seat. Joel’s team moved between safe houses but was still dogged by local PAN supporters and journalists from both sides of the border. Prior to election day, they filled out thousands of false ballots, fabricated to look authenticate, and carefully marked each one in a slightly different hand.

At their polling station in Ciudad Juárez, they arranged for paid PRI supporters to arrive early and slow down the voting, moving at a tortoise’s pace (hence the term ‘tortuguismo,’ or intentional slowness). By the end of the day, few legitimate voters had been able to cast their ballots.

Joel kept a few of these ballots as keepsakes and showed them to me during our interview. On election day, there would be a narrow window of time available to stuff the ballot box. At their polling station in Ciudad Juárez, they arranged for paid PRI supporters to arrive early and slow down the voting, moving at a tortoise’s pace (hence the term ‘tortuguismo,’ or intentional slowness). By the end of the day, few legitimate voters had been able to cast their ballots. Joel spoke with pride when he related these events, noting at one point that “these were strategies I came up with.”

While he spoke without embarrassment about committing election fraud, Joel did not mention that these tactics also relied upon violence. The PRI resorted to longstanding practices of intimidation and physical attacks to control the uneven process of democratic change. Poll observers and media workers were common targets of assault. It was not uncommon for soldiers or thugs-for-hire to physically remove journalists from polling stations or to destroy their equipment.

On election day, eyewitnesses saw unidentified thugs—presumably hired by the PRI—beat up journalists who were trying to photograph unmarked trucks swapping the ballot boxes before the voting had even begun.

Such was the case in Chihuahua, as the federal government sent the military to maintain order prior to and during the elections. When two photojournalists for Diario de Juárez went to the tarmac to document the arrival of military planes to Ciudad Juárez, they were intercepted by soldiers who seized their undeveloped film.4

On election day, eyewitnesses saw unidentified thugs—presumably hired by the PRI—beat up journalists who were trying to photograph unmarked trucks swapping the ballot boxes before the voting had even begun. Other accounts reported threats against reporters who had stationed themselves at the polls. PAN electoral observers suffered similar attacks and in some cases were forcibly removed from polling stations.5

Inter-Party and Intra-Party Violence

Violence could also be a strategy of the opposition. For example, when Joel’s polling station posted the final results (la sábana electoral), it showed that nearly no votes had been cast for the PAN—an absurdity given the party’s popularity in Ciudad Juárez. Local supporters, who were awaiting the tally, were outraged. According to Joel, they started kicking and hitting him, trying to get the ballot box and take it to the municipal electoral commission. He had to call in a military escort to get out safely.

As in Chihuahua, the southwestern state of Oaxaca witnessed manipulations and targeted violence that responded to citizen mobilization. Concerted leftist opposition by the COCEI (Coalition of Workers, Peasants, and Students of the Isthmus) prompted the national PRI to designate a more progressive candidate, Heladio Ramírez, for the 1986 gubernatorial race. Ramírez, in turn, selected a like-minded candidate for the municipal president seat in Juchitán. This selection outraged local PRI conservatives. Backed by the business elite, they showed up at the PRI candidate’s home with weapons and physically threatened him and his family. He promptly withdrew his candidacy.6 Violence was a strategy that shaped electoral possibilities before ballots were cast.

Violence was not a new tool of electoral politics, but one that became more controversial amidst heightened expectations of fair elections and critical coverage by national and international media.

Despite denunciations of fraud, the PRI declared that it had won the municipal elections in Juchitán and nearly every contest in the state of Chihuahua. National and international media reported evidence of fraud and large-scale civil protests took over Chihuahuan cities for weeks. In relating the PRI’s victory, Joel seemed proud that, against all odds, the ruling party had taken the elections. But its methods were not as subtle as Joel thought. The PRI’s candidates did not convince the majority of voters that they had won legitimately. Manipulating the vote and intimidating journalists and observers were longstanding tactics that the PRI’s operatives refined in the 1986 elections. But the use of such blatant methods during Mexico’s most observed elections to-date was a sign of an ailing party that had lost its powers of persuasion.

An analysis of the 1986 midterm elections reveals that violent confrontations and blatant attempts at fraud accompanied democratic contestation. This remained the case over the following years. In 1988, during Mexico’s most competitive presidential elections in decades, hired thugs robbed ballot boxes at gunpoint. The elections ended with the scandalous “crash” of the electronic vote tally system and the subsequent announcement of PRI victory. In 1994, the assassination of PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio shocked the nation and suggested thatno politician should consider themself safe. Violence was not a new tool of electoral politics, but one that became more controversial amidst heightened expectations of fair elections and critical coverage by national and international media.

Conclusion

Joel described the PRI’s electoral victory in Chihuahua as the result of a careful strategized and skillfully executed fraud. Unspoken, however was the fact that intimidation and assault were critical to making these strategies work, particularly when it became more difficult to pay off the opposition.

As in 1986, there is great anticipation of what this year’s mid-term elections will mean for Mexican politics. With myriad municipal posts, 300 congressional seats, and 15 state governorships in play, some observers paint the contests as a referendum on democracy and on the sitting president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), whose MORENA party swept the 2018 elections.7

Foreign media are also sounding alarms about electoral violence, citing the murders of politicians and candidates between September 2020 and June 2021. But an examination of electoral contests during Mexico’s so-called democratic opening dispels assumptions that violence is a new mode of electoral politics or a sign that the state has now lost control to drug trafficking organizations.

Notes

- Interview by author, Mexico City, Mexico, November 15, 2011. Joel is a pseudonym I am using protect this individual’s anonymity. ↩︎

- Paul Gillingham, “‘We Don’t Have Arms, but We Do Have Balls’: Fraud, Violence, and Popular Agency in Elections,” in Dictablanda: Politics, Work, and Culture in Mexico, 1938–1968, ed. Paul Gillingham and Benjamin T. Smith (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 151. ↩︎

- See, for example, Paul Gillingham and Benjamin T. Smith, eds. Dictablanda: Politics, Work, and Culture in Mexico, 1938–1968, ed. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014). ↩︎

- “Arribaron anoche tres aviones con soldados: Decomisaron rollos a fotógrafos,” Diario de Juárez, July 2, 1986, 2. I discuss this incident in chapter 6 of my book, Citizens of Scandal: Journalism, Secrecy, and the Politics of Reckoning in Mexico (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020). ↩︎

- Alejandro Avilés, “Frente a la mentira y el engaño,” El Universal, July 9, 1986, 5. See also José Conchello, “Urnas, deudas, bayonetas y plegarias,” El Universal, July 10, 1986, 4, 8; David Orozco Romo, “Qué las marrullerías os acompañen,” El Universal, July 10, 1986, 5. ↩︎

- Jeffrey Rubin, Decentering the Regime:Ethnicity, Radicalism, and Democracy in Juchitán, Mexico (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), 183. ↩︎

- Enrique Krauze, “Mexico’s President May Be Just Months Away From Gaining Total Control,” New York Times, March 15, 2021. ↩︎