Since the 17th of December 2014, and the highly broadcast and simultaneous announcement by Barack Obama and Raul Castro of renewed relations between their two countries, North American delegations have successively visited Cuba and negotiations have been organised. Indeed, since the handshake between the two presidents at Nelson Mandela’s funeral in 2013, a mutual inclination towards rapprochement was to be expected. It became official following the two messages sent from Washington and the Havana, announcing a modest and historical agreement on tangible measures: the liberation by Washington of three Cuban agents imprisoned in the United States since 1998, and, in return, the liberation of Alan Gross, imprisoned in Cuba since 2009, as well as relaxation measures towards the lift of the embargo and the free circulation of people.

The reactions in Latin America were immediately unanimously in favour. For the Secretary General of the Union of South American Nations (USAN), Ernesto Samper, “it is time to revive the hemispherical relations with the United States”. The Secretary General of the Organisation of American States (OAS), José Miguel Insulza, declared that the two parties had shown a “remarkable generosity of spirit”, and has urged the American Congress to “take the necessary legislative measures to lift the embargo against Cuba”. The President of Panama, Juan Carlos Varela, shared his hopes that it would enable the accomplishment of the “dream” of a “united region” at the seventh Summit of the Americas, which will be hosted in his country in April 2015. Cuba (which until then had refused to join the OAS in spite of the official invitation it received in June 2009) has already confirmed its participation to the Summit, and Obama has announced his presence on the 10th and 11th of April with his peers from the rest of the continent.

In unison with all of the Americas, Barack Obama declared in Spanish during his televised “show” of the 17th of December: “We are all Americans”, thus surreptitiously inscribing the progressive restoration of diplomatic relations with Cuba in the line of Democrat President Monroe who, in 1823, declared “America to Americans” against the European claims on the hemisphere. By insisting on the issue of the economic embargo, Barack Obama has presented the Cuban policy of his country in the past fifty years as a failure1 . Whilst the breakdown in relations with Cuba and the embargo imposed to the island since 1962 aimed at pressuring the regime towards a political and economic opening, the President of the United States has observed that this strategy has been counter-productive, and has contributed to the pursuit of authoritarian politics and economics in Cuba.

Indeed, the embargo has contributed to feeding the Castrist argumentation according to which the difficulties of the Cuban economy came from this permanent attack from the United States and not from the inefficiency of a Soviet-style state economy and the carelessness of Cuban leaders. However, it is not at all certain that the lift of the embargo (if the Congress under Republican majority votes the principle) will allow for a spectacular recovery of the Cuban economy, and even less for a political liberalization of the communist authoritarian regime. Besides, a new wave of arrests of dissidents late December has clearly enshrined the determination of the Castrist regime to maintain its political dictatorship.

© “No one can take away our hope” – Omar Rodriguez Saludes

© “No one can take away our hope” – Omar Rodriguez Saludes

The perspective of renewed economic relations stands at the heart of the normalization process…

Thus, on the 30th of December 2014, only two weeks after the announcement of the forthcoming normalisation of relations between the United States and Cuba, the Cuban political police has either arrested or assigned to residence several personalities from the cultural world, in order to prevent an unauthorised protest. The blogger Yoani Sanchez has announced on the Internet that she was held captive at her residence by agents, and that her husband, Reinaldo Escobar, had been arrested by their building alongside with the dissident Eliecer Avila. She was also able to communicate the arrest of several opponents, and notably of the artist Tania Bruguera. The latter had indeed planned to organise an artistic performance on Revolution square in the Havana, near the government’s headquarters, although without obtaining the necessary authorisations (which are never given to the applicant in these types of cases). The artist had provocatively considered to open a forum on the plaza in which the citizens of the street could briefly express themselves on “the themes that concern them”.

This did not prevent in any way the American and Cuban delegations to meet in the Havana on the 21st and 22nd of January to prepare a roadmap in order to re-establish bilateral diplomatic relations, with the mutual reopening of embassies in each of the two countries as a potential first step. The second round of these formal negotiations, which was held on the 27th of February 2015 in Washington, mainly led to the decision of opening an embassy of the United States in Cuba before the Summit of the Americas in the coming April. Following this, as soon as the 18th of February 2015, the Cuban Minister for Foreign Affairs, Bruno Rodriguez, received an official visit from a Congressional delegation of the House of Representatives of the United States, led by the Democrat Nancy Pelosi who made it clear that her aim was to further the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries. Josefina Vidal, the General Director for American affairs of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Cuba, was also present at this meeting; she will preside over the Cuban party of the Washington meeting of the 27th of February.

Little information has leaked on this closed meeting, if only that the delegation “will work to further the relations between the United States and Cuba by relying on the work done by many Congressmen for many years, in particular on agriculture and commerce”2 . Apparently, economic questions are at the heart of these meetings, much more than political and human rights abuse issues, at the contrary of the affirmations of the vice-Secretary of State for the Western hemisphere, Roberta Jacobson, which underlined in January that the negotiations would be a long and complex process given the “deep [bilateral] differences”.

© “Everything for sale” – Omar Rodriguez Saludes

© “Everything for sale” – Omar Rodriguez Saludes

… of which political issues are significantly absent.

According to the Cuban negotiator Josefina Vidal, these political questions were never discussed during conversations of the 21st and 22nd of January3 . The divergences on the economic model are indeed probably more preoccupying for the North Americans than the abuses of individual and public liberties as it would seem that the recent arbitrary arrests were neither brought up in January nor in February. In support of this hypothesis of economic preference, it should be noted, on the one hand, that the only actor from “civil society” which met the North American delegation of Democrat parliamentarians in February was the cardinal Jaime Ortega. And on the other hand, that the arrival of this delegation coincided with the visit of another North American group, made of three senators, also Democrats, and there to explicitly explore the possibilities of commercial relations with the island. The senators particularly noted the opportunities in the agricultural and tourism sectors and have underlined the “entrepreneurial spirit” of the Cuban private sector4 .

The economic consequences of the lift of the embargo would indeed be important: first for the North American investments in all the sectors, as it was done in Vietnam after the normalisation of relations between the two countries, while the Europeans were kept at bay; second for the Cubans which would undoubtedly see the betterment of the material conditions of their everyday lives. Furthermore, the agreement between the United States and Cuba comes at a time where the economy of Venezuela, which was maintaining Cuba under life-support, is in a catastrophic situation as a result of the Chavist management and the fall in oil prices. If the United States were to replace Venezuela, which is currently transferring 4 to 5 billion dollars per year, the strong rise of these financial flows to Cuba would benefit the regime’s public servants.

It is important to recall here that the dismantling of the Eastern bloc from 1989 onwards and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 have had extremely serious consequences for Cuba. Within a few months, the island had lost the major part of their commercial partners and its entire production system was questioned. Besides, the price of sugar on the global market had fallen. External commerce had then dropped by 75% in volume in comparison with the previous era of exchanges with the USSR, and in 1991 the GDP dropped by 35%; and the population’s purchasing power was divided by two. The “Cuban Revolution” was entering a deep crisis. In 1992, Fidel Castro thus announced the “Special Period in Time of Peace”. It was then that the United States opted for the deathblow strategy and reinforced the blockade: the Toricelli bill of 1992 and the Helms-Burton bill of 1996 transformed the North American embargo in a global blockade by threatening with sanctions the third countries susceptible of doing business with Cuba.

During the summer of 1994, the economic crisis reached its peak in Cuba. The value of the national currency had become untenable compared to the dollar, the life conditions of the average Cuban changed in often dramatic ways. In August, several boats were hijacked from the Havana to the United States and the pirates were welcomed as heroes in Miami by the anti-Castrist Cuban exiles. Thirty thousand Cubans left for the continental shores on rafts, leading President Clinton to close the borders because of the flow of balseros, which were then deported to Guantánamo, a United States military base in Cuba.

It was not before the early 2000s and without doubt thanks to the timely Venezuelan economic support, that a new turn on the United States’ policies could finally take place, authorising money transfers from individuals residing in the United States to their relatives in Cuba on the one hand, and on the other by opening the trade of food and pharmaceutical goods towards the island. The United States then became the largest provider of foodstuffs in Cuba, by ensuring between 35 and 45% of food imports.

In the meantime, the ties between Cuba and Venezuela remained strong: despite the economic variations, the ideological and strategic agreement on political authoritarianism became stronger, as demonstrated by the continual intensification of political repression in Venezuela since the election of Maduro. Thus, since the visit of Nicolás Maduro in Cuba on the 21st of February 2015, the Venezuelan president who spoke to both Castro brothers was able to appreciate that the Cuban regime once more expressed its “immovable solidarity” with Venezuela and President Maduro. The economic and political ties between the two countries since 2000 were underlined, focusing on a time where a global agreement had been signed which notably included an energy clause stipulating the delivery to Cuba of 100 000 barrels of oil a day.

The Cuban leaders also confirmed their absolute rejection of the declarations and actions of the United States and the OAS which “feed and promote internal subversion” against their South American brother country. They thus supported the claims of a conspiracy by the opposition against the legitimate President Maduro, and those of an attempted coup, planned attacks and conspiracies hatched by “foreign interventions” against the “sovereignty, independence and free determination of the Venezuelan people in favour of the Bolivarian Revolution”5 .

Indeed, Cuba cannot drop the ball here, as the achievement of the new policy promoted by Obama may clash with the American Congress, which is now held by a Republican majority. The reservations of a large part of Republicans are well known, they are the strong partisans of the mano dura (“strong hand”), as the Latin American expression goes. Thus Jeb Bush immediately declared that the “beneficiaries” of this decision would be the “abject Castro brothers, who have oppressed the Cuban people for decades”. And John Boehner, President of the House of Representatives, considered that these measures aiming at lifting certain of the restrictions from the island were new “concessions to the insane dictatorship which mistreats its people and is paramount to conspiring with enemies”6 .

This strong opposition is relayed by the leaders of anti-Castrism as the senator of Florida of Cuban origin Marco Rubio, who promised to do “everything in his power” to block the acts of the President at the Congress level. The Cuban-American representative for Florida, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, has considered that the “erroneous action of President Obama […] is another propaganda coup for the Castro brothers who will now fill their coffers with more money, at the detriment of the Cuban people”. However, Obama might find a majority in Congress in favour of his new policy as, in addition to the unwavering support of John Kerry and the head of the Democrat majority of the Senate, Harry Reid, as well as of the senators Dick Durbin and Jim McGovern, polling results from February 2015 show that 56% of Americans now declare themselves in favour of an increasing normalisation of relations with Cuba and that their opinion of Cuba has never been as good in the past 20 years7 . It could be added that the business environments are particularly favourable.

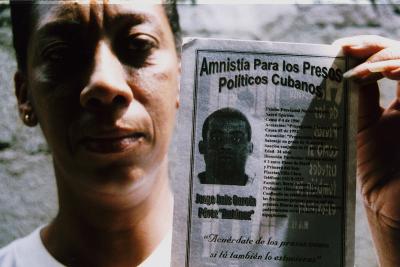

© “Amnesty for Cuban political prisoners” – Omar Rodriguez Saludes

© “Amnesty for Cuban political prisoners” – Omar Rodriguez Saludes

From one protector to the next?

However, wouldn’t this lift of the embargo constitute a defeat of democracy to economic benefits (first for the United States and only collaterally for the Cuban population or maybe only even a part of it)? Symbolically, lifting the embargo is paramount to recognising the legitimacy of the Cuban state-led economic system, which, in the past, has dispossessed all the owners of private businesses of the island, foreign and Cuban. But if the regime changes the basis of this policy now and adopts, as did the Chinese, a claimed capitalism, this argument at the core of the opposition to the lift of the embargo could indeed be set aside. However, the Chinese example, if it is ever adopted in Cuba (a project that is currently not made clear), is both an extremely aggressive and unequal capitalist economic model and a political model which remains the one of a dictatorship not really inclined to any form of political liberalisation as demonstrated by the current re-taking of Hong Kong.

Whether or not the embargo is lifted, the Cubans risk having to resist for a while longer against a liberticide and economically not efficient regime. The film Return to Ithaque by Laurent Cantet (released in 2014 and notably starring Isabel Santos, Jorge Perugorría, Fernando Hechevarria and Nestor Jimenez) offers a very successful vision of the Cuban dead end. It is an excellent film, intelligent, subtle, nostalgic and very politically sensible. It shows all the horror of Stalinian regimes and all the charms of the tough and soft great island; and of the Havana in particular, alive and decrepit.

A small group of old friends from their youths meets again nowadays, to celebrate the return of one of them who had left for Madrid in the 1990s. In the time of the “Special Period”, life has become even harder in Cuba. It is also the time of the failure by Gorbatchovians in their attempt to undermine the regime, which they would pay with their lives. The General Arnaldo Ochoa Sanchez and his camp aid Jorge Martinez Valdes, Antonio de la Guardia and Amado Padron were sentenced to death and executed while tough prison sentences were inflicted upon ten other accomplices including the Minister of the Interior José Abrantes (he was condemned to 20 years in prison and died in captivity from cardiac arrest in 1991). The trial was broadcast live at television in the purest fashion of the Stalinian purges. Compared to this time, their communist youth leads the friends into a facetious nostalgia, rich in typically Cuban swearwords. But the discussion, then the fight, and later the reconciliation, happen around the issue of leaving and of returning to Cuba. Because even though they are all lucid and critical, they remain Cuban and left-wingers, without any complacency for neither the Castrist regime nor for the capitalist world of today, disenchanted and vain.