The IMF and their local allies in West Asia and North Africa (WANA, also known as MENA) have attributed the region’s developmental crisis to insufficient economic openness. On the basis of this claim, the same parties push WANA economies into adopting export-oriented development models. To date, those models have failed, and rather spectacularly so, to yield notionally desired results. Failure must be understood in light of the extra-economic determinants of value. This factor predisposes WANA economies to external imbalances. This is because the determinants in question, primarily political and legal in their nature, arbitrarily reduce the value of exported commodities, on the one hand, while increasing the value of imported goods on the other. Knock-on effects in terms of the incurrence of debt follow, and with them, structural restraints on WANA economies’ growth potential.

The IMF and Export-led Growth

Inasmuch as the IMF assumes the role of ‘lender of last resort’ in many parts of the world, its level of activity in a given region offers a good indication of the prevalence of trouble. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the IMF has significantly increased its activity in WANA oil importing countries, establishing recurring lending arrangements with Tunisia, Egypt and Jordan.[1]

In the framing of the IMF, the troubles facing the three countries derive from a handful of structural problems. Like other adherents of neoliberalism, the Fund attributes significant causal power to currency overvaluation and insufficient integration into the global economy, the latter caused by restrictions on capital inflows and high tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. Per the IMF’s line of argumentation, these variables engender two drags on development. First, they insulate local businesses from competitive pressures, thereby limiting productivity growth and overall economic efficiency. Second, they undermine the international competitiveness of domestic goods, thereby hindering export performance while generating external imbalances.[2] On the basis of this diagnosis, the Fund’s policy prescriptions emphasise current and capital account liberalisation alongside the floating of national currencies, amongst other things.[3]

Myriad issues compromise the IMF’s analysis and the reform agenda it informs. To start, there is the empirical challenge presented by the world’s most export-oriented economies also ranking amongst the world’s most underdeveloped and crisis-prone economies. Whereas China and Japan are lifted up as paragons of export-led development, the fact is that exports constitute a greater percentage of GDP for the struggling economies of sub-Saharan Africa and the WANA region.[4] Excluding the oil and gas producers, exports represent approximately 25% GDP across the WANA region, a significantly larger percentage than what is observed in east Asia and 2.5 times the corresponding figure for the United States. There is also the illogic inherent to the IMF’s proposals. Most pertinent here is the ‘fallacy of composition’: Whether the IMF’s export-centric prescriptions retain validity in a vacuum or not, in the context of a world economy, they are self-cancelling; after all, one country’s exports imply and require another’s imports. As such, the simultaneous pursuit of export-led growth by all cannot yield universal gains, as at a system-wide level, it undercuts the demand for imports which is needed for export-led growth to be successful.

The Value-added Corollary

Without acknowledging the logical incoherence of its recommendations, the IMF has, in recent times, nuanced its approach by specifying that export-led development hinges on the value-added levels of a country’s exports. Alas, the Fund’s revised thesis also falls short. This is principally due to the inadequate treatment of value. In keeping with neoliberal orthodoxy, the IMF posits value as a characteristic of the commodity itself shaped by economic factors such as consumer preferences, utility, and productivity. The reality, however, is that value is a function of a complex and contested process. It is established, at least in part, through the interplay of contemporary and historic political forces, with the value of some commodities being suppressed and others elevated on that basis; at a fundamental level, valuation is not a purely economic phenomenon but a political and legal one mediated by history.

Recent decades in the WANA region provide abundant examples of commodity value being manipulated by extra-economic determinants. On the upside, OPEC’s action to cut supplies of oil to Western countries in 1973, resulting in the 1973/4 oil crisis, quadrupled the price of oil in just a few months. Almost overnight, the value added of oil skyrocketed, and did so on the back of a politically-induced supply shock.[5] Downside examples from the region are, of course, more numerous. In the 19th and 20th century, for instance, Britain worked tirelessly on the behalf of its textile industry to bring down the price of cotton. Nevertheless, after the American civil war (1861-1865), the price of cotton increased massively as a result of the embargo imposed on the American South, which was the largest supplier of cotton to the Lancashire textile factories in Britain.[6] This price boom had a huge and lasting impact on Egypt, a major grower of cotton at the time. Incentivized by the prices on offer, Egypt would dedicate a third of its cultivable land to cotton production.[7] Simultaneously, the country would see age-old textile craftsmanship erode due to local industry’s inability to compete with industrially produced British textiles, as also occurred in India, the Levant, China and Turkey.[8] When the price of cotton ultimately collapsed as direct result of British policy–principally, efforts designed to future proof the textile industry against supply shocks by way of expanding cotton production across the empire, in India most of all–Egypt succumbed to successive waves of acute economic crisis. One of the more intense begat the Urabi revolution and thereafter, British colonisation of Egypt.

Mindful of this history, re-industrialisation became one of the key pillars of Egypt’s independence aspirations. And starting in the 1930s, meaningful progress was made in reindustrialising the economy, with energy and capital flowing into textile production in particular. Alas, by the time this process began, the spread of textile production around the globe had created downward price pressures on the commodity, pushing it into the lower value-added tier of manufactured goods.[9] This structurally reduced the developmental gains Egypt was able to derive from industrialisation. By extension, the economy’s dependence on the export of primary goods, cotton especially, endured well into the post-war era. This dependence would in many ways define the parameters of possibility for the Egyptian Republic, established in 1953. Though major efforts were put into industrialising and urbanising the economy, reliance on the import of machinery from the global north hamstrung Egypt’s infant industries while straining the country’s balance of payments through unequal exchange.[10] Unequal exchange laid the path to external indebtedness. The combination of burdensome repayment obligations and creditor-imposed policy change, in turn, made changing the terms of exchange nearly impossible. Similar dynamics played out for the countries of western North Africa (maghreb). There, production followed cues laid down by colonial France. This initially confined the region’s exports to (forcibly) undervalued primary commodities like phosphate rock and agricultural goods like citrus fruits and olive oil. Later, it locked them into low value, factor driven and labour-intensive manufacturing.

Obstructions to Development: Dealing with Structure

As this brief review attests, variables exogenous to the WANA region and structural in nature play a significant role in defining the course of national development. Ranking senior amongst such variables is today’s globalised trade regime. Contrary to the claims put forth by the regime’s champions–who pledged the liberalised trade would power a convergence in development outcomes[11]–globalisation, as institutionalised since the mid-1980s, has contributed to divergence in a great many instances. The primary reason for this is the manner with which the current trade regime resolves trade imbalances between nations. For all effects and purposes, it has done so through subjecting trade deficit countries to expanding systems of economic and political control. In the first instance, these systems are entrenched through the loans and foreign direct investment inflows that fund trade deficits. More recently, they have also been deepened through deficit countries’ making themselves open to speculative capital exports from surplus countries. The latter dynamic is visibly evinced in the WANA region, where these kinds of capital exports have been leveraged by oil exporters to exert control over oil importers.

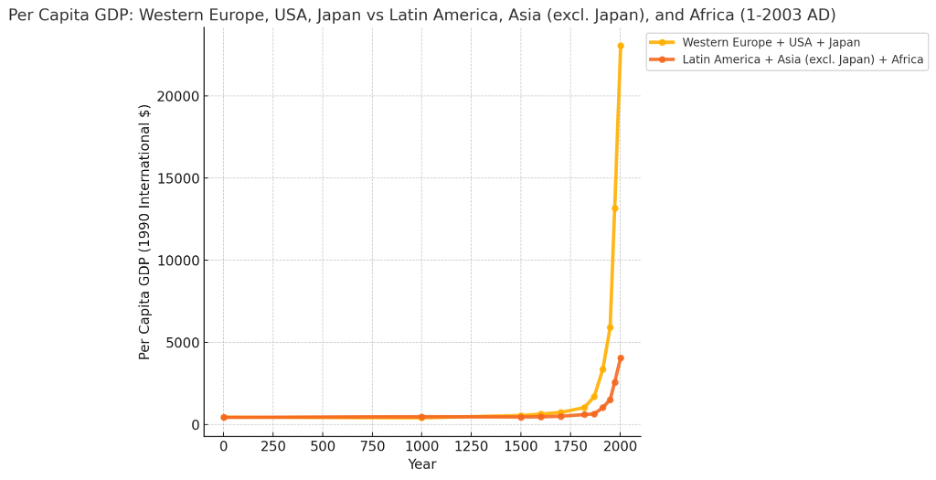

Prior to the 1970s, wealth was distributed relatively equally across the WANA region. Within each country, of course, class structures mediated significant inequalities of both income and wealth. Due to the two major oil supply shocks of the 1970s, however, everything changed, and a regional version of the Great Divergence commenced (See Figure 1). The first shock broke with the 1973 October War; by virtue of Arab oil-exporting countries deciding to cut supplies to countries that supported Israel, oil prices witnessed a four-fold increase over the span of a few months. The second stemmed from the Iranian revolution of 1979. Thereafter, oil prices skyrocketed from about $4 a barrel in 1973 to almost $40 by the end of the decade.

Figure 1: The Great Divergence

Until the 19th century, the world showed little variance in development levels. Inequalities remained pronounced, of course, but were mediated by local class relations rather than geographic variables. Where spatial divergences in income and wealth holdings did emerge, moreover, they primarily resulted from leaps in productive capacity in China and India: what we know today as the global north lagged behind.[12] With the industrial revolution and attendant consolidation of modern capitalism, everything shifted quite quickly. In the space of a few hundred years, the concentration of global wealth in the global north became quite extreme.[13]

- Source: Based on data from table A7 from Maddison, Angus. Contours of the world economy, 1-2003 AD: Essays in macro-economic history. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

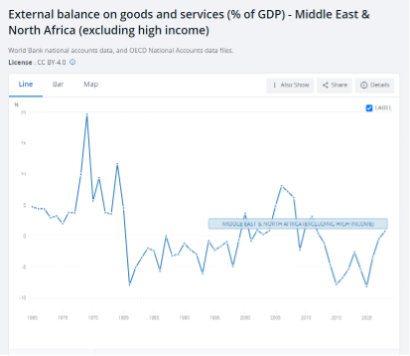

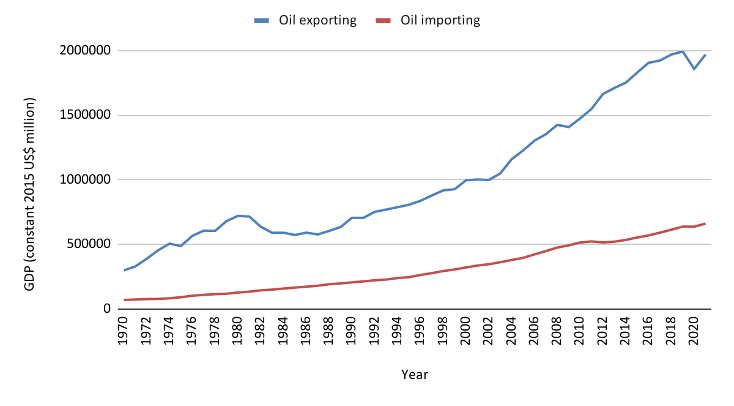

Pronounced as the oil boom’s impact was on the global economy, its effects on the regional economy of the WANA were perhaps even more consequential. At the most basic level, the boom created massive trade surpluses for oil-exporting MENA countries, and massive trade deficits for their oil importing counterparts. After consistently running trade surpluses during the early post-colonial period, from 1981 to 2023, low and middle-income WANA countries would run trade deficits in 31 of 42 years (See Figure 2). The performance would be even worse if oil exporters like Libya, Iran, and Algeria were excluded from the calculation. For a time, these deficits were partially closed by flows of remittances and aid. Ultimately, however, they set WANA’s oil exporters and importers on to entirely different trajectories. For the importers, the course was set for debt and developmental crises (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: The falling surpluses and growing deficits of oil-importing MENA countries (1965-2023)

- Source: World Bank Data, “External balance on goods and services (% of GDP) – Middle East & North Africa (excluding high income)

Figure 3: The WANA Great Divergence

- Source: Author calculations based on figures from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD

- *Oil exporting countries: Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Libya, UAE.

- **Oil importing countries: Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Syria, Sudan

- ***Excluded West bank and Gaza, Yemen, Jordan and Lebanon because the unavailability of data before 1980

WANA Importers’ Double Deficit

The trade deficits suffered by oil-importing WANA countries have been compounded by a deficit of a second and perhaps more salient kind. The latter can be appreciated through consulting a relatively new trade dataset known as Environmentally Extended Multiregional Input Output (EEMRIO). At the highest level of abstraction, EEMRIO allows researchers to calculate the movement of embodied resources implied in the exchange of internationally traded commodities. EEMRIO provides a country-by-country look at the balance of biophysical resources, tracking the transfer of raw materials, energy, labour and land that is exacted through the trade of commodities. Widening the scope beyond the monetary imbalances of trade, EEMRIO affords a look into the realities of ecologically unequal exchange (EUE).[14]

Expectantly, WANA’s oil exporters are significant net exporters of raw material equivalents (RMEs) and embodied energy. This is despite their importing of large amounts of embodied labour and land via the exchange of commodities. The imports in question speak to these countries’ shortcomings in terms of economic diversity and their resulting dependency on external sources for labour-intensive goods and land-intensive agricultural products such as food and textiles. The picture is more troublesome for WANA’s oil-importing countries. Though to a lesser degree, they too are net exporters of RMEs and energy (see Table 1). However, their biophysical balance shows a higher degree of unequal exchange. These countries export rather massive sums of embodied RMEs in order to acquire fairly small sums of embodied labour. Given the environmental stresses already bearing down on countries like Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt, the strains being incurred through the export of high volumes of RMEs are especially acute in impact. Climate change-driven drought lasting for six years has significantly reduced Morocco and Tunisia’s crop yields, forcing both countries to scale up imports of foodstuffs at great cost to the trade balance.[15] In Egypt, water shortages are becoming more intense in part due to Ethiopia’s construction of the Renaissance Dam, threatening Egypt’s already insufficient water share from the Nile equivalent to the levels of 1959, when the country’s population was only one fourth of what it is today .[16]

| Table 1 Transfers of embodied resources in WANA trade (2015) | |||||

| Population | total net import of RMEs [t] | total net import of embodied energy [GJ] | total net import of embodied land [ha] | Total import of embodied labour [p-yeq] | |

| Oil exporting | 134,922,576 | -1,570,549,157 | -1,998,920,629 | 25,730 | 13,918,032 |

| Oil importing | 239,164,933 | -430,582,631 | -48,427,642 | -70,745 | 260,115 |

| Source: Author’s calculation based on data provided in: Dorninger, Christian, Alf Hornborg, David J. Abson, Henrik von Wehrden, Anke Schaffartzik, Stefan Giljum, John-Oliver Engler, Robert L. Feller, Klaus Hubacek, and Hanspeter Wieland. “Global Patterns of Ecologically Unequal Exchange: Implications for Sustainability in the 21st Century.” Ecological Economics 179 (January 2021): 106824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106824. | |||||

The other side of the valuation coin

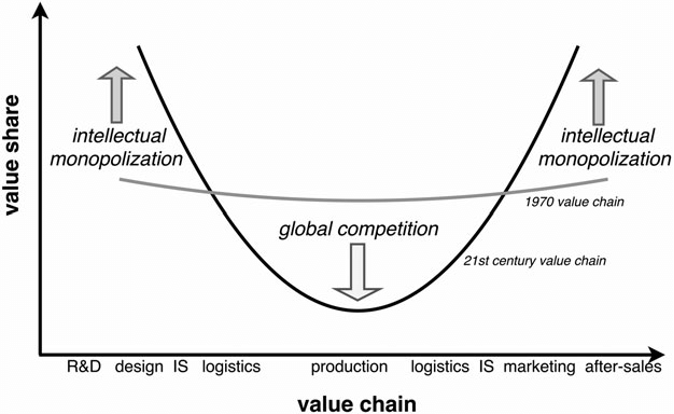

The WANA region’s Great Divergence reveals a great deal about the global economy today. Most immediately, it shows that the monetary values of commodities are neither intrinsic to them nor purely determined by economic forces. Politically-induced supply shocks or cartel activity, after all, can shift prices of a commodity overnight and forever change the course of development history in the process. What should also be apparent from the Great Divergence is that the solution to the WANA’s economic and environmental crises will not be found in some perfect design of economic policy. The scaling of resource-intensive exports may yield temporary income gains, though at the expense of compounding ecological costs. Moving national economies into higher value-added production lines, meanwhile, will never be achieved without engaging the political domain. In the first instance, the global value regime must be transformed to more closely reflect the value that resource-intensive primary commodities and factor-driven secondary commodities present to economies and societies. In the second, it must be changed to reduce the value accruing to the Global North on the back of its intangibles–its control of design, marketing, distribution, research and development, and the like.

Downgrading the value of intangibles will require addressing the prevailing system of intellectual property rights (IPR). This system was institutionalised first through the World Trade Organisation’s Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) and later through bilateral trade and investment deals pushed by Global North countries. It has facilitated what amounts to the monopolisation of knowledge, granting firms in the global north monopolistic control over key technologies, standards, and brands. For some indication of scale, consider the concentration of patents and trademarks in developed economies: In 2013, 82.5% of triadic patents were registered in the US, EU, and Japan, with developing countries having but a minimal share of the total.[17]

Operating through global value chains, Durand and Milberg have shown how control of intellectual property supercharges international inequality. On the one hand, northern firms’ holdings of IP and intangibles of a similar kind impose cutthroat competition among suppliers in Global South countries. The results of this competition are dual: weakened bargaining power for labour in the Global South–and attending declines in wages–and an asymmetric distribution of value along the supply chain (See Figure 3)[18]: Due to issues of oversupply, the enforcement of IP claims, and the monopsony of power of northern multinationals, with firms at the bottom and middle rungs of the manufacturing and assembly processes are today accumulating ever lesser levels of capital despite productivity enhancements.[19] On the other hand, holdings of IP are facilitating staggeringly large flows of rent to northern firms. In 2023, high income countries received over $472 billion in IPR payments, compared to just over $16 billion for low- and middle-income countries.[20] This is also a grave underestimation of IPR-related flows; determining the volume of IPR transfers is effectively impossible as for many IPR-heavy products, such as patented pharmaceuticals, electronics and machinery, one cannot establish with any degree of certainty how much of the total product price derives from an IPR monopoly premium .

As major importers of patented pharmaceuticals, machinery, electronics, as well as services such as royalties, media and entertainment, franchises and branding, and ICT products (e.g. software licences), WANA countries contribute no small amount to these rents.[21][22]

Figure 4 The ‘Growing Smile’ of value distribution

- Source: Durand, Cédric, and Wiliiam Milberg. 2019. “Intellectual Monopoly in Global Value Chains.” Review of International Political Economy 27 (2): 404–29. doi:10.1080/09692290.2019.1660703.

The reordering of world capitalism around intellectual property holdings, a pivot driven by politics and institutionalised via the law, lowers the developmental horizon for all the non-oil exporters of the WANA region. Just as distressingly, control of intellectual property is allowing economies in the Global North to preserve their ecological capital via trade. A study conducted by Hickel et al. in 2022 established that in 2015, Global North economies, on a net basis, acquired 12 billion tons of embodied raw material equivalents (RMEs) from the rest of the world, 822 million hectares of embodied land, 21 exajoules of embodied energy (equivalent to 3.4 billion barrels of oil), and 188 million person-years of embodied labour. The study’s authors estimate the value of these appropriations at $10.8 trillion in Global North prices.[23]

In view of all this, it should be clear that the WANA region’s underdevelopment is not a function of insufficient integration into the global economic system, but rather, of the manner with which the region has been integrated. By dint of historical and political reasons, this process has led to the undervaluation of commodities exported by WANA countries lacking significant endowments of oil and gas, and the overvaluation of imported commodities. As such, to change the region’s trajectory and extract it from recurring cycles of crisis will require a challenge to the international political order.

This publication has been supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. The positions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

[1] Diab, Osama. “Out of Inflation Control: The IMF and Rampant Inflation in MENA” AUC School of Global Affairs and Public Policy (GAPP), 2024.

[2] The IMF has stuck to this explanation of crisis for a number of decades running. A report on the WANA regions struggles from 1997, for instance, attributed major responsibility to lags in terms of trade. Specifically, the report’s authors asserted that deficiencies in trade liberalisation ‘had a negative impact on production efficiency and will become more costly given the increasing globalisation and integration of the world economy’. The report also stated that this lag would reduce the region’s attractiveness for foreign investment. See: Alonso-Gamo, Patricia, Susan Fennell, and Khaled Sakr. “Adjusting to New Realities: MENA, the Uruguay Round and the EU-Mediterranean Initiative”

[3] Alonso-Gamo, Patricia, Susan Fennell, and Khaled Sakr. “Adjusting to New Realities: MENA, the Uruguay Round and the EU-Mediterranean Initiative” imf.org, 1997

[4] Diab, Osama. “Africa’s Unequal Balance.” Review of African Political Economy 50, no. 175 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2023.2190453

[5] Walton, John K., and David Seddon. Free markets and food riots the politics of global adjustment John K. Walton ; David Seddon. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

[6] Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A global history. New York: Vintage Books, 2015.

[7] Diab, Osama. 2023. “Prebisch and Singer in the Egyptian Cotton Fields.” AfricArXiv. June 20. doi:10.31730/osf.io/g69ed

[8] See Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A global history. New York: Vintage Books, 2015.

& Panza, Laura. “De‐industrialization and Re‐industrialization in the Middle East: Reflections on the Cotton Industry in Egypt and in the Izmir Region.” The Economic History Review 67, no. 1 (July 28, 2013): 146–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0289.12019

[9] Panza, “De‐industrialization and Re‐industrialization in the Middle East.”

[10] Gad, Mohamed. Mādhā jarā limashrūʿ Ṭalʿat Ḥarb? Miṣr wa-al-niẓām al-mālī al-ʿālamī fī miʾat ʿām (What happened to Talaat Harb’s project? Egypt and the international financial system in a 100 years). Cairo: Dar Al Maraya , 2021.

[11] Baldwin, Richard. The Great Convergence. Harvard University Press, 2016.

[12] Pomeranz, Kenneth. The great divergence: China, Europe, and the making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021.

[13] Ibid.

[14] In the eyes of EUE theorists, the widening of scope is necessary because prices do not fairly or comprehensively represent the value contained in trade exchanges. As such, a monetary balance of trade leaves a great deal out of the picture. Per Lauesen and Cope, prices do not explain value because it is prices that need to be explained. Hickel et al. similarly argue that prices ‘reflect, among other things, the (im)balance of power between market agents (capital and labour, core and periphery, lead firms and their suppliers, etc); in other words, they are a political artefact.’

See: Lauesen , Torkil, and Zak Cope. “Imperialism and the Transformation of Values into Prices” Monthly Review, July 27, 2015

Hickel, Jason, Christian Dorninger, Hanspeter Wieland, and Intan Suwandi. “Imperialist Appropriation in the World Economy: Drain from the Global South through Unequal Exchange, 1990–2015.” Global Environmental Change 73 (March 2022): 102467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102467.

[15] Metz, Sam. “Climate Change Imperils Drought-Stricken Morocco’s Cereal Farmers and Its Food Supply” AP News, July 24, 2024

[16] Mohy El Deen, Sherif. “Egypt’s Water Policy after the Construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam” Arab Reform Initiative, February 27, 2023

[17] Ibid

[18] Hamoud, Maher, and Osama Diab. 2022. “A Growing Smile and a Growing Demise: The Diminishing Value of Damietta Furniture Making.” AfricArXiv. November 28. doi:10.31730/osf.io/r2tnf.

[19] Durand, Cédric, and Wiliiam Milberg. “Intellectual Monopoly in Global Value Chains.” Review of International Political Economy 27, no. 2 (September 5, 2019): 404–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1660703.

[20] World Bank Data. “Charges for the Use of Intellectual Property, Receipts (BOP, Current US$) – Low & Middle Income, High Income” World Bank Data, 2024

[21] The Atlas of Economic Complexity. “Northern African Imports by Product Category, 2021”

[22] The Atlas of Economic Complexity. “Western Asian Imports by Product Category, 2021”

[23] Hickel, Jason, Christian Dorninger, Hanspeter Wieland, and Intan Suwandi. “Imperialist Appropriation in the World Economy: Drain from the Global South through Unequal Exchange, 1990–2015.” Global Environmental Change 73 (March 2022): 102467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102467.