Introduction

Since 2020, Oman has embarked on one of the most ambitious green energy initiatives in the world: targeting $140 billion in investments between now and 2050 to reorient the Omani economy away from fossil fuels and towards becoming one of the largest green hydrogen exporters in the world. The numbers are staggering: 300 million solar panels, 10,000 wind turbines, 180 gigawatts of renewable capacity, and 100 gigawatts of electrolyser capacity, to be built between now and 2050.[1] The government hopes that the green economy will supply 55% of Oman’s new jobs between now and 2050, with 70,000 in the hydrogen sector alone.

By betting big on the green transition, and green hydrogen in particular, Oman hopes to draw in foreign investment, increase domestic innovation, and decarbonise its economy to achieve net zero by 2050. Based on almost a dozen interviews and a variety of public sources, this article looks at the challenges the sector faces, but also the serious institutional and political groundwork that has been laid to ensure that Oman is well-positioned to capitalise on future global demand for hydrogen.

Why Oman

China produces more hydrogen electrolysers than the rest of the world combined and is the world’s largest producer and consumer of hydrogen. Japan is the only country that has brought commercial hydrogen-fueled vehicles to market, and the EU has the world’s most far-reaching hydrogen mandates. So why is it that, on a per capita basis, Oman has by far the most ambitious green hydrogen strategy in the world?

The first part of the answer is geography. Oman is one of the sunniest countries in the world. It also has a long and predictably windy coastline, meaning that, as a person familiar with a green hydrogen project in Salalah stated, “renewable energy quality here is second-to-none.” Having one of the lowest population densities in the Middle East factors, too: there is more than enough space to build vast renewable energy sites without angering hordes of NIMBYs. A final geographic benefit is location: Oman is midway between East Asia and Europe, the areas expected to be the largest future green hydrogen markets.

Second is politics. Oman set up a new entity, Hydrom, in October 2022 to masterplan the country’s hydrogen strategy, regularize the tendering process, and bring continuity to the execution of the national hydrogen strategy. A person involved in developing export infrastructure between Oman and Europe said that “There is consistency in Oman’s planning. They are moving very steadily towards the realization of their vision.” Part of that vision has been to create a more transparent process around land reservation agreements: instead of deals being signed directly with the Minister of Energy and Minerals, interested parties have to go through a public auction process and sign deals with Hydrom instead, creating more clarity around prices in addition to more contractual certainty. One person familiar with the Hydrom auctions said the process was more investor-friendly than what came before: “Hydrom will think of rules of engagement, the Minister [of Energy and Minerals] will put it into a ministerial decree and then it’s basically law. We would negotiate, they would discuss, and a decision would be taken the next day, and they would come back to us.” A person familiar with the second round of auctions said the Ministry of Energy and Minerals “was “one of the best ministries I’ve ever interacted with. Incredibly competent, incredibly receptive.” Several interviewees also emphasized that Oman’s long and close relationship with European countries and political stability made it an appealing partner: political risk is low, institutional willingness is high.

Strategies and Institutions

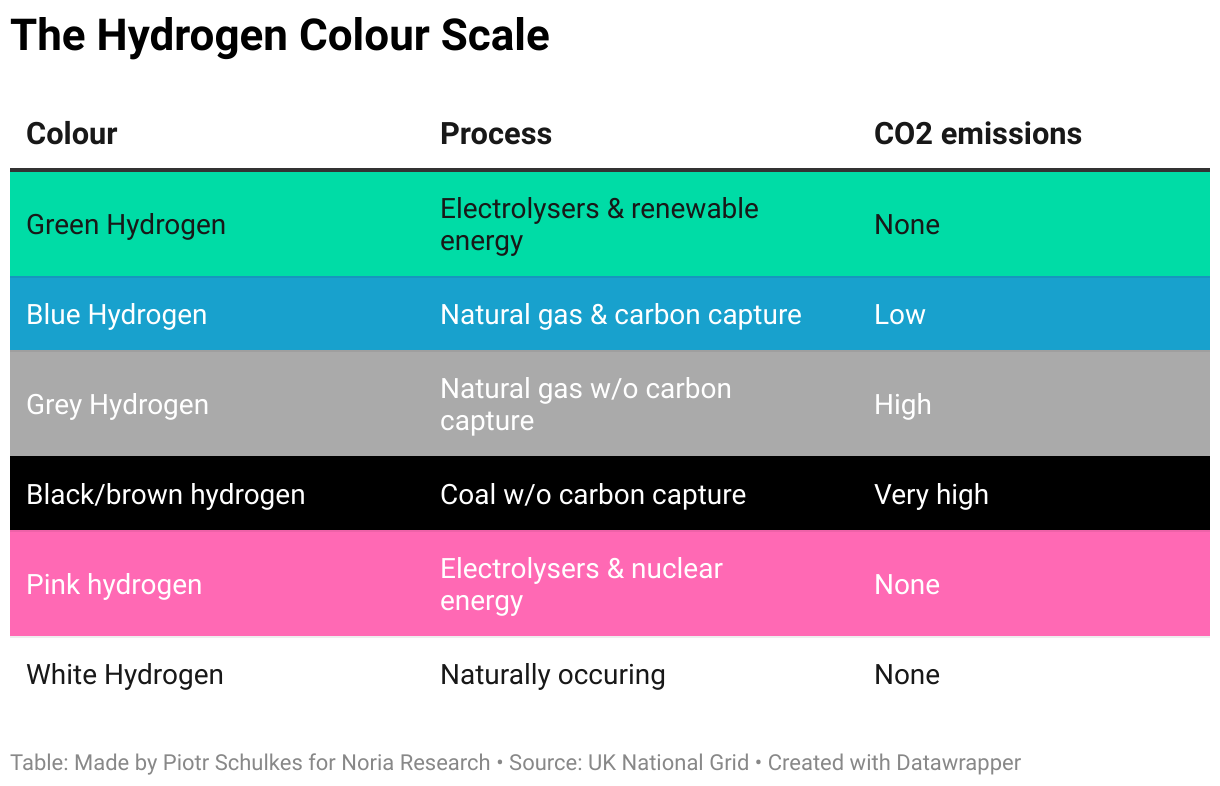

Oman’s green hydrogen strategy was announced in October 2022. By 2030, the strategy targets 8-10GW in electrolyser capacity and 16-20GW in renewable capacity to create up to 1 million tonnes per year (mtpa) of green hydrogen. By 2040, plans call for 3.25mtpa in green hydrogen production, realized through 35-40GW in electrolyser capacity and 65-75GW in renewables capacity. By 2050, the goal 7.5-8.5mtpa in green hydrogen output, which will require inputs of up to 185GW of renewable energy powering 100GW of electrolysers.[2] To put this all in perspective, when Oman’s strategy was announced the total global installed electrolyser capacity for hydrogen production was about 700MW.[3] Should Oman achieve its targets, by 2040, the country’s hydrogen exports would represent 80% current LNG exports in energy-equivalent terms. The 2050 target of 8.5mtpa would double the energy contents of current LNG exports.[4]

These heady goals were announced in the context of skyrocketing energy prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when for a period green hydrogen was cheaper than grey hydrogen.[5] The IEA wrote in 2023 that “Oman has the potential to become one of the most competitive producers of renewable hydrogen” in the world.[6]

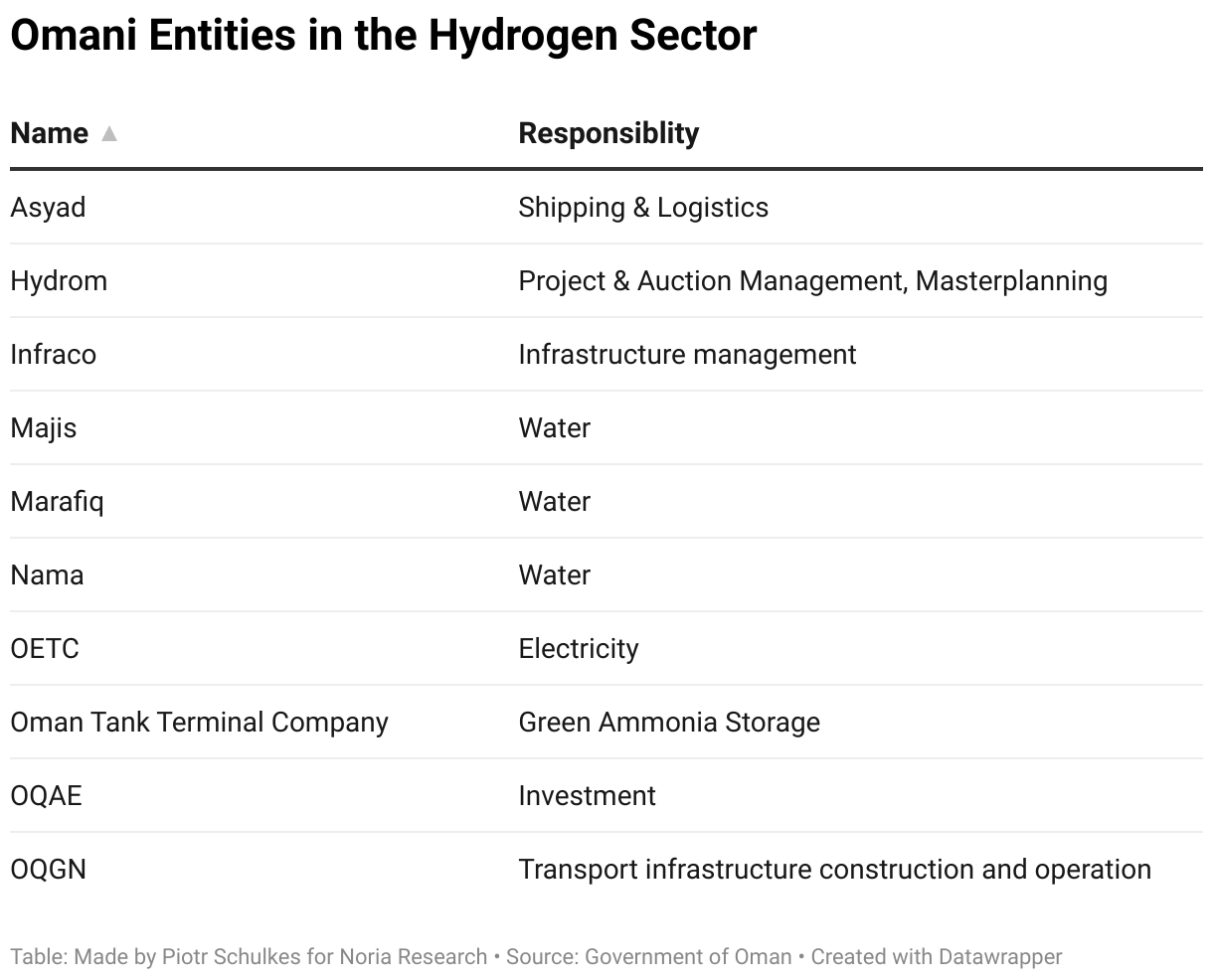

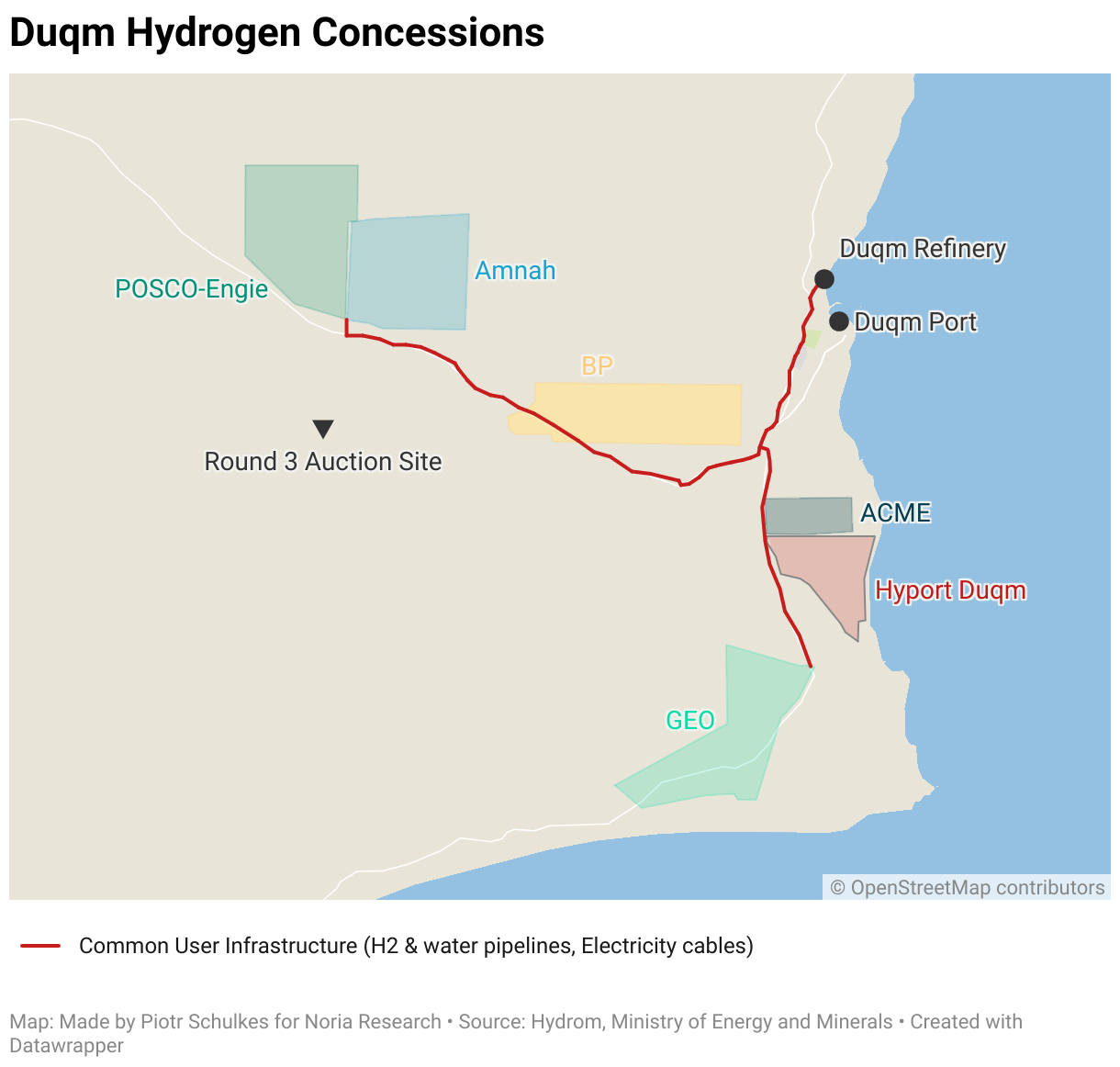

Capitalising on this burgeoning interest, Oman launched the aforementioned Hydrom (also known as Hydrogen Development Oman) in October 2022. Hydrom is wholly owned by the Omani government through Energy Development Oman, a major player in the Omani energy sector, and is led by the former chairman of Oman’s national utilities company. As intimated, Hydrom is mandated to “master plan the [hydrogen] sector”, including on regulatory design, overseeing auctions, facilitating the development of shared infrastructure, and coordinating logistics.[7] Projects that existed before Hydrom, including a BP-run project, Hyport Duqm, and Green Energy Oman, were given priorities on land allocation but were required to match the prices from the open Hydrom auctions.

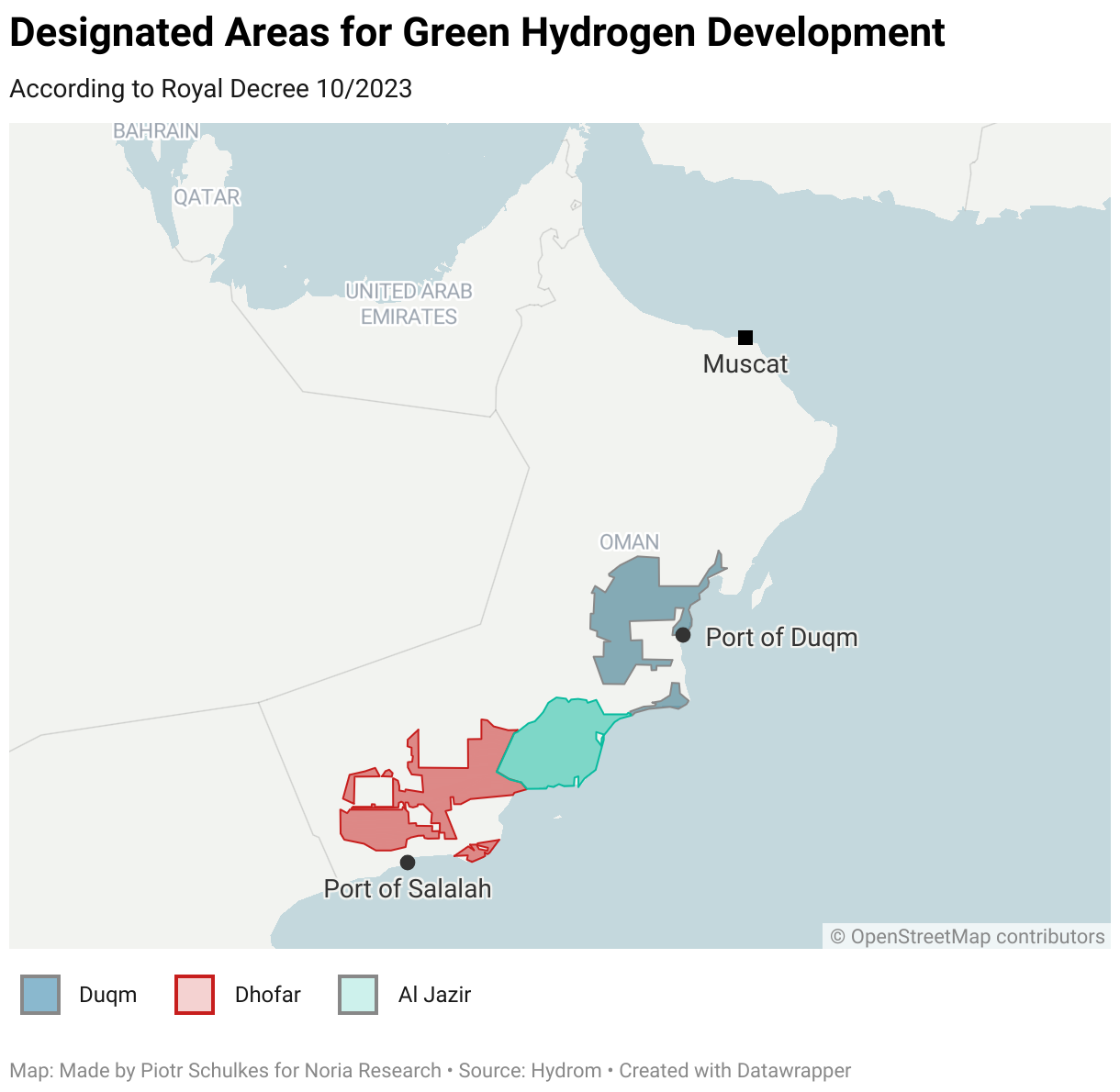

In February 2023, Royal Decree 10/2023 was promulgated, which allocated 50,000km2 of land for renewable energy and clean hydrogen projects. Management of the land was placed under the control of Hydrom.[8] The IEA estimates that this land, located in the Al Wusta and Dhofar governorates, is enough to produce 25m tonnes of hydrogen per year, three times Oman’s 2050 target.[9]

Several other Omani entities are involved to realize these ambitions. OQ, the national oil company, is an investor in three legacy projects: Through a subsidiary called OQAE, it holds stakes in SalalaH2, Hyport Duqm, and Green Energy Oman. OQ also retains a back-in right to purchase a 20% stake in any of the projects auctioned by Hydrom.

While the projects are expected to produce their own electricity through solar and wind, Omani firms will be responsible for some common user infrastructure. Electricity infrastructure will be handled by the Oman Electricity Transmission Company (OETC). Water will be handled by Nama, the Omani state-owned utilities company, though Marafiq, which operates utilities in the Duqm special economic zone, and Majis, which provides water utilities in Sohar, will also play a role. OQGN, another OQ subsidiary, is the sole owner and operator of Oman’s natural gas transmission network and will also be responsible for operating the Omani hydrogen pipeline system once it is built. At the time of writing, OQGN is developing the commercial and regulatory framework for hydrogen transport, including economic incentives.[10] According to the company’s 2024 annual report, it last year spent OMR 940,337 (~$2.44 million) on hydrogen and CO2 pipeline construction, and had spent another OMR 34,028 (~88,200) by Q2 2025.[11] InfraCo, set up in December 2023 to set up to oversee the development of the common hydrogen infrastructure, is still inactive according to March 2025 financial filings.[12]

What is notable about Hydrom, and the Omani hydrogen sector in general, is that Omani government entities are primarily playing facilitating roles. Oman does not have a state-owned renewable energy giant like Saudi Arabia has in ACWA Power or the UAE has in Masdar, and policymakers appears to have made the decision that bringing in foreign expertise is the easier and cheaper way of expanding its hydrogen industry.[13] Developers in the sector are predominantly private actors, with state-owned OQ at most taking at 20% stake through its back-in right. Using foreign knowhow to execute plans drafted by the government is a method Oman knows well: Several of its ports are jointly owned with European firms, its electricity transmission system is minority-owned by the Chinese national grid operator, and its renewable energy projects are built by foreign entities.

Hydrom and the ecosystem it’s building indicates that the government of Oman is focusing its energies on what it knows – logistics and project management – while expanding its role in enabling industries, like wind turbine production.[14] Two people interviewed for this article, one from the steel industry and a former employee of OQ, believed that Oman will repeat its oil industry experience with hydrogen by building up the sector with foreign specialists before focusing on Omanization down the line. This line of thinking was echoed by the individual familiar with the hydrogen auctions, who said “I think the Minister of Energy, the Oman Investment Authority, and the Minister of Finance can convince the cabinet that it’s more important to get the investments in and then job creation will follow later.”

The Projects

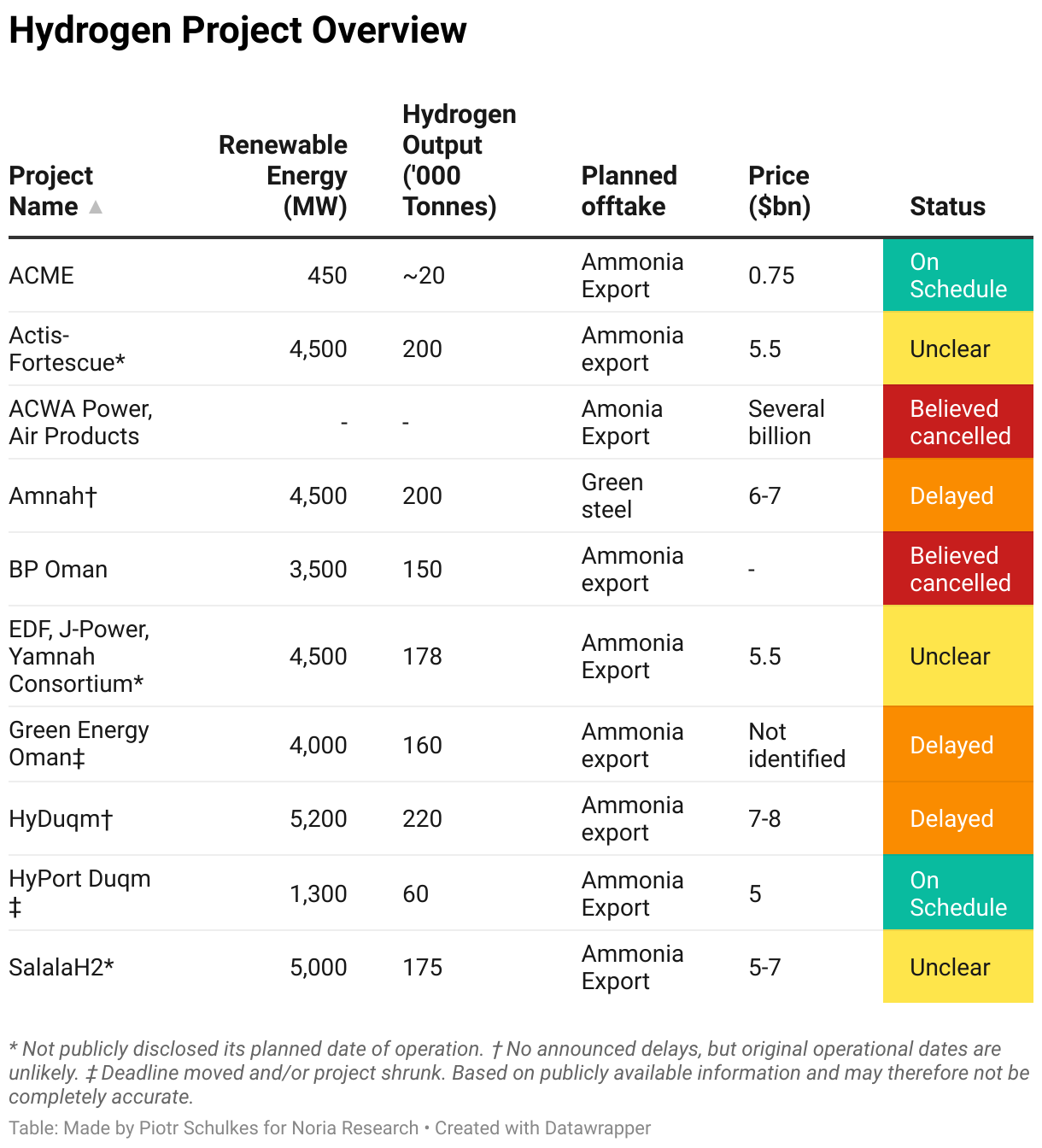

Hydrom requires winning developers to cover the full green hydrogen value chain: developers are tasked with building renewable energy sites, producing hydrogen, turning hydrogen into a derivative product, and finding markets (i.e. offtakers) for the goods in question. The hydrogen derivative most favoured by firms is ammonia due to ammonia transport technology being more mature than that of liquid hydrogen transport. For that reason, many projects are interchangeably described as green hydrogen or green ammonia projects.

Funding for the projects comes from debt raised by developers, equity stakes, and offtake contracts. The third of these options has presented major bottleneck issues, which will be discussed more below. Hydrom offers some incentives, including a 90% reduction in land lease fees during the early stages of project development, reduced royalty payments in the early years of operation, and corporate tax exemptions for up to 10 years. Beyond this, there does not appear to be state-led financing initiatives; ACME Group’s project in Duqm, the only project that has entered the construction phase, received major funding from Indian governmental entities.

First Round – Duqm

The first auction round awarded two projects around Duqm. The project won by the Amnah consortium targets 200,000 tonnes per year (200 ktpa) of green hydrogen to be exported and used in local green steel production, with an intended start date in 2028. The project won by the HyDuqm consortium, which consists of Korea’s Posco Holdings, Samsung Engineering, Engie, and three other firms, likewise targets 200 ktpa in hydrogen production as feedstock for 1.2mtpa of ammonia. For its energy input, the consortium plans to develop of 5GW of wind and solar capacity.

Three legacy initiatives were also given land grants in Duqm. Green Energy Oman (GEO) is a joint venture between OQ, Shell, and three other firms, which plans to produce 150ktpa of green hydrogen from 4GW of renewables for up to 1mtpa of ammonia export in its first phase.[15] In an earlier press release the company stated its ambition to have a project fuelled by 25GW of renewable energy at full capacity.[16] BP also received a land allocation for a green hydrogen project to create 150,000 tonnes of green hydrogen.[17] However, the continued existence of BP’s exclusive project is unclear due to the company’s investment in another project: in July 2024 BP announced it bought a majority stake in the third Duqm legacy project, Hyport Duqm, a joint venture between DEME and OQ. This project targets 180ktpa of hydrogen production and 1mtpa of ammonia.[18]

Second Round – Salalah

In April 2024, Hydrom’s second public auction awarded two projects in the area around Salalah port. The first, won by a consortium of EDF, J Power, and Yamna, aims to produce 178ktpa of green hydrogen for 1mpta of ammonia by 2030, using 4.5GW of renewable energy to power 2.5GW of electrolysers.[19] The second project, a joint venture between Actis and Fortescue, is of a similar size: 4.5GW of renewables for 200ktpa of green hydrogen, to be sold to local offtakers and processed into derivatives for export.[20]

In December 2023 Hydrom also awarded OQ, Marubeni, Dutco, and Samsung C&T a green hydrogen block to create hydrogen and ammonia from 4GW of renewable energy. Based on a May 2025 presentation by two of the project partners, its planned to be operational in 2030.

Other projects

In December 2021 ACWA Power, OQ, and Air Products signed an agreement to develop a $6.5bn project, but this endeavour has not been mentioned in any later Hydrom publications.[21]

A final project that did not fall under any of the hydrogen auctions is the ACME-led project in Duqm. Scatec, originally a partner, stepped out of it in 2023,[22] though at the time of writing it is the only green hydrogen project in Oman that has entered the construction stage. In March 2024, Yara, a Norwegian fertilizer company, signed an offtake agreement for 100ktpa of green ammonia, the first of its kind in the world.[23] During the initial phase, the ACME-led project targets 100ktpa of green ammonia production based on 450W of renewable energy at a cost of USD 750 million.[24] The project will be increased to 280ktpa over two successive phases (which will operate under Hydrom’s regulatory framework), and is planned to reach a total output of 1.2mtpa fuelled by 5.5GW of solar power when it is fully operational.[25] The speed at which this project gets built and expanded will be a good indicator of the overall trajectory of Oman’s hydrogen sector: the project obtained $484 million in funding in July 2023, signed an offtake agreement in March 2024, and satellite imagery indicates that preparatory construction work started in late summer 2024. The plant is scheduled for commissioning in Q1 2027.

An interviewee said that generally speaking, the time between final investment decision (FID) and start of operations for large-scale hydrogen projects is four to five years. If that tendency holds, most of the projects detailed above would become operational after Hydrom’s 2030 target. With many already facing delays or lacking in specified deadlines, the lag could be significant. To date, the only projects that look to be on schedule are those that either reduced their scope or opted for a phased approach to construction.

Infrastructure

Infrastructural expansion is vital for facilitating Oman’s hydrogen ambitions. Plans on this front can be placed in two categories: transport infrastructure and power and water production.

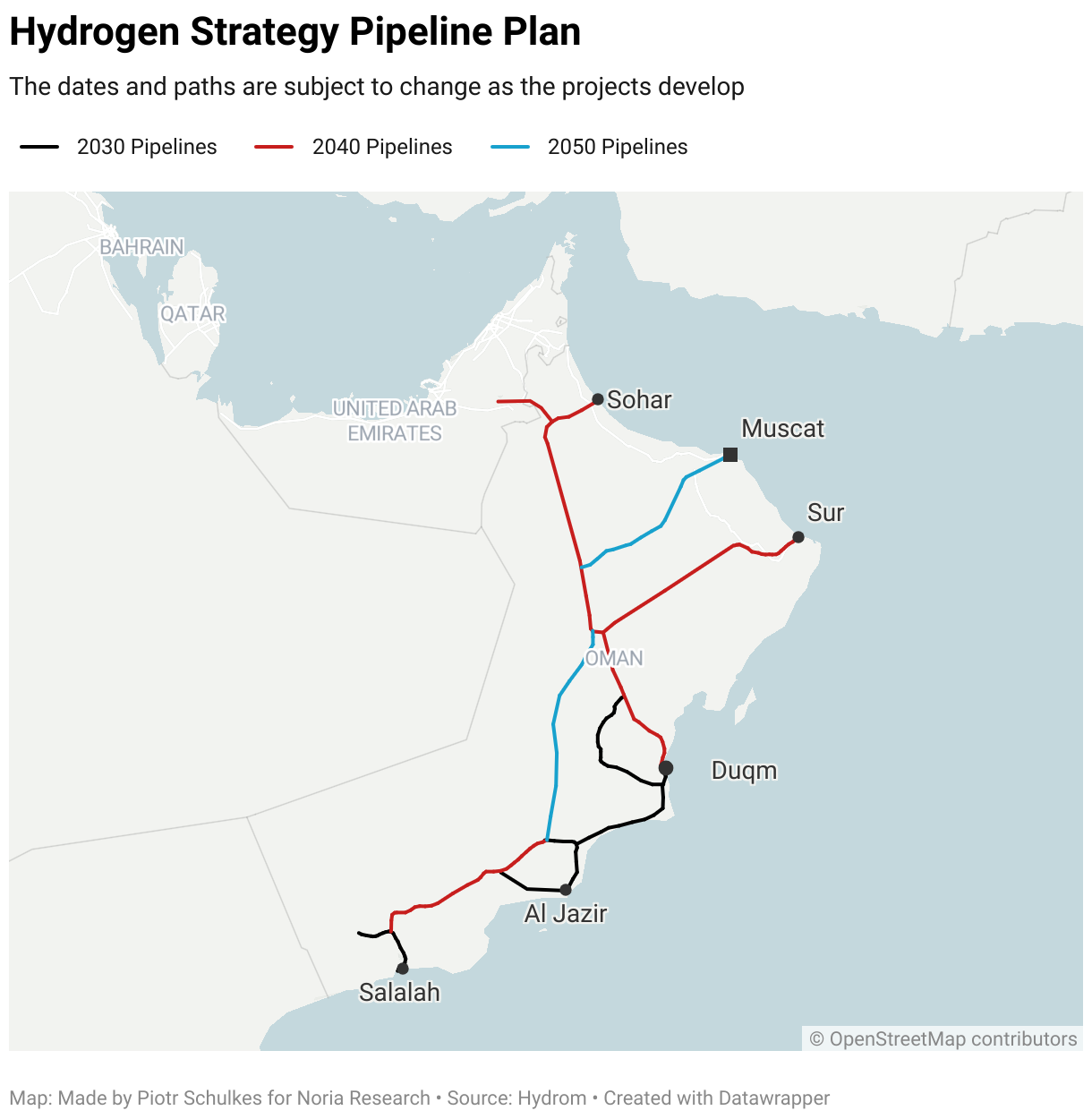

For domestic transport, OQGN plans to build 300-400km of pipelines by 2030, with a final investment decision scheduled for 2027.[26] However, according to the company’s financial statements, OMR 974,000 ($ ~2.53 million) has already been spent on preparatory work. The first phase will be pipelines in the Al Jazir, Duqm, and Salalah concession areas. In the second phase, these pipelines will be joined together, and additional infrastructure will be built to facilitate overland export to the UAE. In the third and final phase, scheduled to be completed by 2050, pipelines will link Muscat to the hydrogen system. Asyad Group, an Omani logistics firm, estimated that a proposed 1,000km pipeline between the south and north of the country will have a capacity of 500,000 tonnes of hydrogen per year.[27] Considering the much larger volumes developers are planning to produce, long-distance in-country transport of hydrogen is likely to play a minor role for the overall sector, with the majority of hydrogen produced near export terminals or industrial offtakers.

Indeed, a second consideration of perhaps greater priority is coastal export infrastructure. Oman already exports about 200ktpa of ammonia through its ports, but the country’s facilities will need to expand by orders of magnitude to facilitate its green ammonia export plans. Salalah Port has an ammonia storage facility at the time of writing, but the port nevertheless plans to expand its infrastructure as demand for green ammonia grows. Sur, in the north, also has some ammonia export infrastructure, and in Duqm, Dutch tank storage firm Vopak entered a joint venture with the Oman Tank Terminal Company in October 2025 to build energy storage facilities.[28] Infrastructure expansion in Salalah and Duqm will be prioritized over Oman’s other ports, as these two will be the main gateways for the planned green hydrogen projects.

Oman is also pioneering new transport technology to better use its competitive advantage for cheap hydrogen exports. In April 2025, the Netherlands and Oman signed a joint development agreement for a liquified hydrogen transport corridor between Duqm and the Port of Amsterdam.[29] Liquified hydrogen shipping is a small industry (there is one ship globally at the time of writing), though it offers some clear advantages for Oman. Currently, the easiest way to transport hydrogen is to convert it to ammonia by adding nitrogen, which can be transported at -33C (hydrogen must be transported at -253C). However, once the ammonia arrives at its destination, it has to be “cracked” to split the nitrogen and ammonia, an energy-intensive and therefore expensive process. The advantage of liquid hydrogen transport is that the energy-intensive stage of the process (the cooling) happens in Oman where energy is cheap, while ammonia cracking happens in the Netherlands, Germany, or Japan, where energy is more expensive. However, as the small size of the global liquid hydrogen shipping fleet indicates, the technology has not reached commercial viability yet. One person familiar with the liquid hydrogen export plans puts it this way: “The individual technologies of this process are mature, with the focus now on applying them at scale.” The upshot is that while liquid hydrogen transport has theoretical advantages in cost, transport, and ease of offtake, the technology is not yet widely used. Ammonia transport, on the other hand, has proven technology applied in a well-developed market spanning the globe.

Power and Water

Oman is a water-stressed country, and while it may seem reckless to situate a water-intensive industry like hydrogen production there, a closer look at the numbers suggests this is not the case. IRENA estimates that one kilogram of green hydrogen requires 17.5kg of water.[30] Assuming that Oman reaches its 2050 target of 8.5mtpa of hydrogen production per year, it would need about 144.5bn kilograms of water, or 144.5 million m3. This is undoubtedly a large volume of water. With large-scale desalination, however, it can be reached without undue trouble. The Ghubrah III desalination plant will have a capacity of 300,000m3/day once it is completed.[31] As such, the amount of freshwater required to reach its hydrogen goals by 2050 would equal the capacity of 1.5 Ghubra III plants, or a 30% increase in Oman’s desalination capacity, comparable to the consumption of Muscat governorate in 2024. Not insignificant, but well within reason.

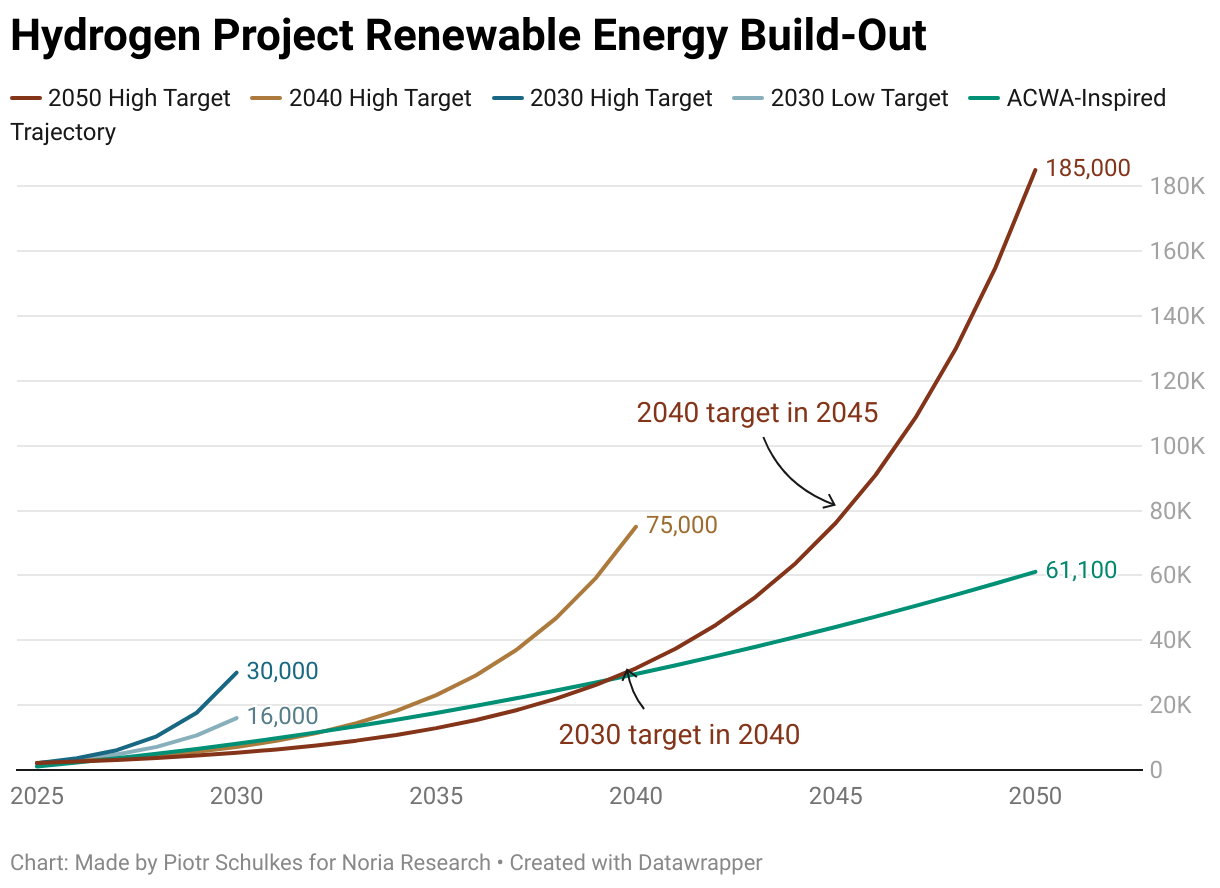

Power production is another story. According to Nama, Oman’s utilities company, electricity generating capacity in Oman in 2024 was 10.2GW. Based on an annual growth rate of 7.2% (which was growth rate from 2023 to 2024 in electricity production), Oman’s non-hydrogen generating capacity would reach about 60GW by 2050. Assuming Oman reaches its goals, the installed capacity of the solar and wind farms that feed hydrogen electrolysis would be three times the capacity of the non-hydrogen economy. Installing this amount of renewable energy is no small task.

Because only one green hydrogen project of comparable size to those in Oman is under construction, estimates on how quickly such projects can be built are imprecise. Based on extant projects in 2025 and announced projects through 2028, the annual growth rate in Oman’s renewable energy capacity is ~21%. For Oman to reach its low 2030 target of 16GW, the growth rate would have to increase to 50%, and to a staggering 70% to reach the high 2030 target of 30GW. This type of scaling is not realistic. For the 2040 targets of 65GW or 75GW, the annual growth rate would have to be 25.6%-26.6%, which is high but within the bounds of reason. The 2050 targets of 175GW and 185GW, would need constant annual growth rates of 19.1% and 19.4%, respectively. While this growth rate is feasible, the scale of actual installation in the late 2040s (~30GW in 2049, ~20GW in 2048) is still enormous. This rate would also entail serious delays to Oman’s announced schedule: the 30GW target, originally scheduled for 2030, would be reached in 2040, and the 2040 target of 75GW would be reached in 2045.

Another possible reference point is the Neom Green Hydrogen Company (NGHC), a which has 2.2GW electrolyser capacity powered by 4GW of renewables. Satellite imagery shows that early construction on the associated solar plant started in early 2023 and the project is scheduled to be operational in early 2027. If we assume that Oman starts out installing green hydrogen-related renewables as fast as the NGHC (at a rate of 1GW/year) but speeds up the process each year to become more than three times faster by 2050, Oman still only manages to install 61GW by that date, far below its stated goal.

It is possible for Oman to build enough power infrastructure to reach its 2050 hydrogen goals: China built 373GW of renewable energy, twice Oman’s goal by 2050, in a single year in 2024. However, for that there first needs to be a market for green hydrogen and ammonia, and that is where the real challenges start.

The Challenges of Foreign Markets

Based on the time needed to build these projects and the availability of funding, Oman’s 2030 targets for green hydrogen seem out of reach. “No way” was how one person involved in the auctions put it when asked about the feasibility of the 2030 goals. But as the same interlocutor went on to say “This is not Oman’s fault. Oman put a lot of effort into developing the hydrogen infrastructure and rules and regulations because Europe wanted hydrogen, and then two years later Europe didn’t want hydrogen anymore.” This perspective was echoed by a European hydrogen expert:

“What happened in Europe is that there was enormous hype – that hydrogen was necessary for everything – and because of that the expectations were inflated enormously, and the timelines became very unrealistic. Plans that Germany and the Netherlands believed would be partially operational by 2025 or 2026 and complete by 2030 will now only be ready 2032. The result is that a lot of import projects are struggling to conclude contracts because they cannot get the hydrogen to the location where it is needed.”

The European market for hydrogen is primarily focused on the Netherlands and Germany, two countries whose demand is expected to be high but whose capacity to produce is limited. The two countries have co-funded H2Global, an initiative that hopes to remove some of the risk for early movers in the hydrogen market by signing long-term contracts with sellers and short contracts with offtakers, in addition to covering the price difference between what sellers need and what offtakers want to pay. However, the H2Global programme has a few structural issues that make it an imperfect vessel to kickstart the Omani hydrogen sector.

First is the size of the budget. While H2Global’s second auction has a headline figure of a respectable €3bn,[32] the individual lots are substantially smaller than that, at around €590m.[33] Considering the price of individual projects in Oman is north of €5bn, this, as the person familiar with a Salalah project put it, “doesn’t do a dent” in changing the cost calculus. This perspective was shared by the person involved in Omani hydrogen exports, who said that H2Global’s “carrot is too small; it is effectively compensation of €50 million a year which while substantial isn’t so big that you are suddenly hitting the spot for offtakers.” A second issue is the length of the contracts that Hintco, the H2Global trading entity, signs. Hydrogen purchase agreements are for 10 years, while the sales agreements are for 1 year only. For both producers and offtakers, this is too short: producers would prefer 15-year purchase agreements, while offtakers don’t want to work on one-year time horizons – it’s too unpredictable to make long-term decisions. Third is the size of the lots. The round 1 renewable ammonia lot was for an average of 66ktpa, far below the output of even one of the planned projects in Oman.[34]

Yet Oman’s hydrogen plans haven’t only faced obstacles in Europe. Two other markets highlighted in Hydrom’s launch presentation as “likely major importers”, Japan and South Korea, come with their own set of challenges.

Japan and Korea: Price Sensitive and Pragmatic

Japan has a long history with hydrogen and has put serious political and economic weight behind plans to grow the global hydrogen market. In October 2024, the Hydrogen Society Promotion Act came into effect. The Act’s purpose is to grow the demand for low-carbon (meaning green and blue) hydrogen, and the Japanese government has set aside $19bn for this initiative.[35] The contract for difference (CFD) structure means the fund compensates hydrogen buyers based on the difference in price between hydrogen and another comparable product. For blue or green hydrogen and ammonia, the comparative reference points will generally be LNG and coal prices, depending on the industry in which these products are used.[36] Through the Act, Japan wants to meet the goals of two other plans, the Basic Hydrogen Strategy and the 2021 Strategic Energy Plan, which target 12mtpa of hydrogen use by 2040 and 1% usage of hydrogen or ammonia in power generation by 2030, in addition to co-firing ammonia at coal-fuelled power plants.[37]

The good news for Oman is that Japan’s hydrogen strategy is deeply anchored in policymaking and industry and has substantial top-line funding behind it. The hydrogen consumers in Japan are also on or close to the coast and are therefore less reliant than their European counterparts on (chronically delayed) transport infrastructure. The less encouraging piece of news is that Japan’s green hydrogen market is likely to remain small for the time being. A Japanese hydrogen expert interviewed argued that “Japan takes a technology-driven approach where they start with whatever technology is mature.” As a result, the country has a strong preference for blue hydrogen, rather than the more expensive (and less mature) green hydrogen. A person familiar with one of the projects in Salalah echoed this, saying that the east Asian markets are “carbon intensity markets”, where CO2 emissions need only be “low enough”; price is a bigger driver than environmental factors. Japan’s CFD tender, the results of which will come in March 2026, is therefore likely to primarily fund blue hydrogen and ammonia projects, to the detriment of Oman’s export-focused projects.

The story in Korea is similar. The weight given to price in a 2024 clean hydrogen auction meant that blue projects were advantaged over renewable energy-fuelled ones.[38] Of greater concern, only 11% of the auction volume was qualified due to the price ceiling of the tender.[39] A second auction in 2025 was abruptly cancelled right before the bid deadline due to changed policy priorities of the new Korean cabinet.[40] For Oman, this means that a hoped-for export market is becoming increasingly uncertain.

Green hydrogen is, for now, only an option in markets with strict mandates for the product. As the person familiar with the Salalah project said, “For green [hydrogen], you need Europe.”

Conclusion

Oman’s hydrogen sector has the fundamentals in place: land on which projects can be built, vast renewable energy generation capacity, political support, and a beneficial geographic location. The one thing missing is a market. As the person familiar with one of the Salalah projects explained, “If there is a market and there are offtakers, the project will be constructed. Other [energy] projects have been made in worse places with more challenging requirements.”

The scale of the Omani projects is a double-edged sword. On one hand, their vast size drives down the price per kilogram of hydrogen, making it more competitive compared to the small-scale production sites in Europe. The drawback is that the capital expenditures required are beyond what many investors and offtakers are comfortable with. According to the person familiar with the Hydrom auctions: “They all need to get an offtaker who needs to sign for at least five to ten years. That would be a five-to-ten-year contract of almost a billion a year in a non-proven market. Who is going to do that?”

With offtakers in Japanese and Korean markets too price sensitive and the European markets too small and slow to develop, Oman has a few options. The first is to incentivize local industry. Two individuals interviewed, one from a steel company and another from an Omani refinery, both said that current projects are export-focused and there are no clear plans the next five years to supply hydrogen to local industrial offtakers. But the Middle East is already the world’s largest producer of direct reduced iron, a market that has huge growth potential and that can position countries like Oman at the forefront of the global green iron and steel trade.[41] Instead of waiting for slow permitting and inconsistent policymaking abroad, moving early and decisively domestically to be at the vanguard of green steel and other industries would give Oman the double benefit of onshoring more of the value chain while supporting the local green hydrogen industry.

A second option is a change in the structure of the Hydrom projects. In the Round 3 investor presentation, it is clearly stated that “phased execution is not permitted.”[42] However, starting at a smaller scale, like the ACME project, would make it easier to find an offtaker and reduce project-to-project risk – the chicken-and-egg problem where to have a market you need production, but you need production to have a market. The person involved in exporting hydrogen from Oman to Europe believed “That the second we start building the import infrastructure, more offtakers will be interested. There is currently an impasse in the hydrogen economy because there is no real market yet.” They believed that the market will grow rapidly once the first steps have been made, and in that scenario the capacity to rapidly build multi-gigawatt facilities will be vital, but phased construction may make the first steps easier.

A third option would be to set up a government subsidy body. This could take inspiration from either H2Global or India’s Power Finance Corporation and REC Limited. Such an initiative could remove some of the uncertainty from the nascent hydrogen industry and allow Oman to develop its supply chains at a more gradual level. However, Oman has only recently emerged from a serious budget deficit,[43] and may therefore be unwilling to put serious money into a largely unproven industry. This policy would also dramatically increase the opportunity cost of the hydrogen industry. At the moment the costs for Oman are concentrated in the human capital side, but subsidies big enough to make a difference for hydrogen developers could draw money away from other Vision 2040 priorities such as education, mining, and manufacturing.

So, what is the outlook for Oman’s hydrogen industry? In the short term, not great. Globally, governments are reducing their focus on the environment and spending more money on defence. Interest rates are up, making borrowing more expensive, and the prices of electrolysers have not come down as much as was expected a few years ago. In the medium term, stricter international laws on sustainable aviation fuels, the growing market for zero-emission shipping, and infrastructure being completed will grow the market for green hydrogen and ammonia. The steady stream of new investments in and adjacent to Oman’s hydrogen sector indicate that, despite headwinds, international interest remains. The country is indeed well-positioned to have a durable and important role in the global hydrogen value chain, and to balance out the trust deficit that exists in the hydrogen industry. The latter is key. Multiple interviewees highlighted that investors, developers, and policymakers have been burnt by hype cycles that promised much but delivered little. While Oman’s projects may be delayed, the fundamentals that make Oman attractive will not change: political support will remain, the wind will keep blowing, and the sun will keep shining.

Photo credit: Ryan Lackey, “Gas/oil storage at Sohar, Oman” (2007).

[1] https://hydrom.om/events/hydromlaunch/221023_MEM_En.pdf

[2] https://hydrom.om/events/hydromlaunch/221023_MEM_En.pdf

[3] https://www.iea.org/energy-system/low-emission-fuels/electrolysers#tracking

[4] https://oqgn.om/UploadsAll/Banners/1713772831500OQGNAR23_English_Version.pdf

[5] https://www.rystadenergy.com/news/cheap-secure-and-renewable-europe-bets-on-green-hydrogen-to-fix-energy-woes

[6] https://www.iea.org/reports/renewable-hydrogen-from-oman

[7] https://hydrom.om/Hydrom.aspx?cms=iQRpheuphYtJ6pyXUGiNqiQQw2RhEtKe#about

[8] https://decree.om/2023/rd20230010/

[9] https://www.iea.org/reports/renewable-hydrogen-from-oman

[10] https://oqgn.om/financial-information

[11] https://oqgn.om/financial-information

[12] https://edoman.om/financial-statements/

[13] The NEOM Green Hydrogen Company in Saudi Arabia is majority-owned by the Saudi government through ACWA and the Public Investment Fund, with Air Products holding a 33% stake. In the UAE, the hydrogen projects are being developed by a constellation of state-owned entities including Masdar and ADNOC.

[14] http://duqm.gov.om/upload/publications/duqm-quarterly-magazine-issue-40.pdf

[15] https://geo.om/about-us.php

[16] https://geo.om/news-details-01.php

[17] https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/what-we-do/bp-worldwide/bp-in-oman.html

[18] https://oq.com/en/investors/financial-statements-and-reports

In its initial stages, note that the project targets are reduced to 60 ktpa of hydrogen for 330ktpa of green ammonia.

[19] https://uae.edf.com/en/news/edf-group-to-drive-green-energy-production-in-oman-with-large-scale-green-ammonia-project

[20] https://www.act.is/2024/04/29/actis-fortescue-consortium-awarded-rights-to-develop-green-hydrogen-project-in-oman/

[21] https://shorturl.at/dL7h1

[22] https://scatec.com/2023/08/18/delivering-on-strategy-and-strong-progression-of-construction-activities/

[23] https://www.yara.com/corporate-releases/yara-and-acme-signed-a-binding-agreement-for-supply-of-green-ammonia/

[24] https://omansustainabilityweek.com/newfront/news/omans-first-green-ammonia-project-begins-receiving-key-cargo

[25] https://acme-ghc.in/oman-project

[26] https://oqgn.om/UploadsAll/Banners/1745733940584AR%20%20E%20%2025.04.2025.pdf

[27] https://asyad.om/docs/default-source/default-document-library/sustainable-impact-disclosure-report-v4-2.pdf

[28] https://www.omanobserver.om/article/1179116/business/economy/vopak-plans-sizable-investments-in-new-energy-park-in-al-duqm

[29] https://energyoman.net/agreements-signed-for-liquid-hydrogen-corridor-partnership-with-royal-vopak

[30] https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Dec/Water-for-hydrogen-production

[31] https://inima.com/en/project/ghubrah-iii/

[32] https://hintco.eu/news/hintco-announces-eu-approval-of-second-h2global-auction-round-worth-up-to-eur-3-billion/

[33] https://hintco.eu/hpa-auctions/

[34] https://hintco.eu/lot-1-renewable-ammonia/

[35] https://www.iea.org/policies/28652-hydrogen-society-promotion-act

[36] https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/programmes/cefim/green-hydrogen/2024-case-studies/Subsidy-scheme-Japan-case-study-2024.pdf

[37] https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/enecho/shoene_shinene/suiso_seisaku/pdf/20230606_5.pdf

[38] https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2573134-south-korea-h2-power-auction-excludes-some-nh3-projects

[39] https://www.yamna-co.com/south-korea-selects-a-bidder-in-the-first-clean-hydrogen-power-auction/

[40] https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/2025-11-05/business/tech/Korea-Power-Exchanges-bid-cancellation-exacerbates-concerns-about-clean-hydrogen-power-market/2436556

[41] https://www.carboun.com/leveraging-green-trade

[42] https://hydrom.om/PreviousRoundResults.aspx?cms=iQRpheuphYtJ6pyXUGiNqgnTvLaOi%2fEP

[43] https://www.mei.edu/publications/balancing-books-deep-dive-fiscal-policy-and-diversification-oman