On April 4, Khalifa Haftar launched the troops of the self-proclaimed “Libyan National Army” on Tripoli, the Libyan capital where the Government of National Unity sits. Marking yet another division since 2014, this offensive undermined the hopes for peace in a country which is still seeking to conclude its political transition after the 2011 revolution. This military offensive placed Libya in a situation of civil war and aroused the attention of regional supporters of the belligerent parties.

The current conflict involves dozens of factions, mainly gathered in two camps. How did this partition of power in Libya take shape?

Seif Eddine Trabelsi, Xavier Guignard: The roots of the Libyan division can be found in the immediate aftermath of the 2011 revolution. Every revolutionary episode is a key moment of possible division, and Libya didn’t escape the rule. The revolutionary forces, which are the new masters of Libya, took a long time to structure a political space, and alienated a part of the political and tribal figures.

After forty years of reign by Muammar Gaddafi, the emerging power of the February 17 revolution prioritised the exclusion of the “Greens” [Gaddafi partisans] from the political horizon. Even if this decision seemed to pursue the revolutionary effort on an institutional level, it nevertheless didn’t distinguish between the various degrees of proximity to Gaddafi’s power.

Their fate was further aggravated by a law issued on May 5, 2013, the so-called “Political Exclusion Act” (qanun al-azl al-siyasi), which forbade the exercise of power for ten years to anyone who served under Gaddafi between 1969 and 2011. For instance, the president of the National General Congress (CGN, Libyan Parliament), Mohamed el-Megaryef, a long-time opponent, found himself excluded for having been ambassador to India before defecting in … 1980!

Thus, the first two post-revolutionary years led the historical opposition to exercise power alone, excluding not only the supporters of the old regime, but also supporters of the regime who joined the revolution from the very first moment.

The law of political exclusion left certain Libyan political and tribal figures without political representation in the new institutions. How did they react?

Some of them didn’t hesitate to question the legitimacy of the General National Congress, or even support all political and/or military attempts to end the political process resulting from the February 17 revolution.

Some of those excluded responded favorably to the call made by Khalifa Haftar1, a former Gaddafi officer who returned from exile when he promised back in early 2014 to “end the chaos” and denounced the legitimacy of the ruling power. In order to do this, Haftar set up an armed group, called the “Libyan National Army”, with which he launched Operation al-Karama (“Dignity”) to bring him to power by means of a military operation. In May 2014, he launched a battle against all the armed groups of the city of Benghazi (East) who opposed him; the fighting lasted for three years.

Khalifa Haftar’s call was also received in western Libya, where armed groups joined him, mainly from the town of Zintan (150 km southwest of the capital), which then attacked the CGN to put an end to its work. The Fajr Libya (“Dawn of Libya”) coalition, which brought together most of the western cities opposed to Khalifa Haftar’s project, occupied Tripoli and blocked the attack led by the ANL and its allies. In the span of a few months, the main Libyan factions were trapped by the division: the “revolutionaries,” who defended the power of Tripoli, against the supporters of Haftar.

Finally, the Libyan division has a regional dimension. The coup in Egypt, in the summer of 2013, radically changed the balance of power in the region because it brought down one of the main governments stemming from the Arab Spring. Haftar found unexpected support in a powerful new regional axis, which brought together Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Khalifa Haftar also received support from France.

Why is the issue of armed groups and local authorities so important in the Libyan context?

Until 2011, power was absolutely concentrated around the figure of one man, Muammar Gaddafi, but the revolution caused its fragmentation. Power was freed from a very small group and fell, almost literally, in new and more diversified hands. In post-revolutionary Libya, it’s no longer the State that holds power or manages public services, but a set of local political forces whose scale and nature vary: armed groups, municipal councils, tribal councils, neighborhood networks, etc.

This focus on locality is the product of a forty-year regime where the state itself was sometimes a threat

This fragmentation of political authority went along with a reduction of individual movement between regions and the primacy of local political identity in the national debate. But the mistake is to consider that this identity is forged against a more inclusive “Libyan” identity when, in reality, it is rather used as default or while waiting for another option. Although these identities are built by well-differentiated local historical trajectories, their daily use reveals more about the absence of national legitimacy than its contestation.

Today, most armed groups and their men accept the principle of disarmament, but the question which irremediably follows is knowing to whom they must surrender their arms, and who will ensure security. This focus on locality is the product of a forty-year regime where the state itself was sometimes a threat. Thus, the question of guarantees and counter-powers to the absolutism of the central state is a key factor in building a pacified relationship between these local political identities and the national reconstruction. In the meantime, alliances and conflicts are formed on the local scale and nourish the dynamics of civil war.

Let’s come back to the attempt to end the 2014 division with the Skhirat Agreement.

The Skhirat Agreement failed because of a lack of inclusiveness. From the outset, it excluded part of the National General Congress (CGN), among them the Islamist forces, and it didn’t integrate the different factions of the old regime.

This political balancing act crystallized the division more than solving it

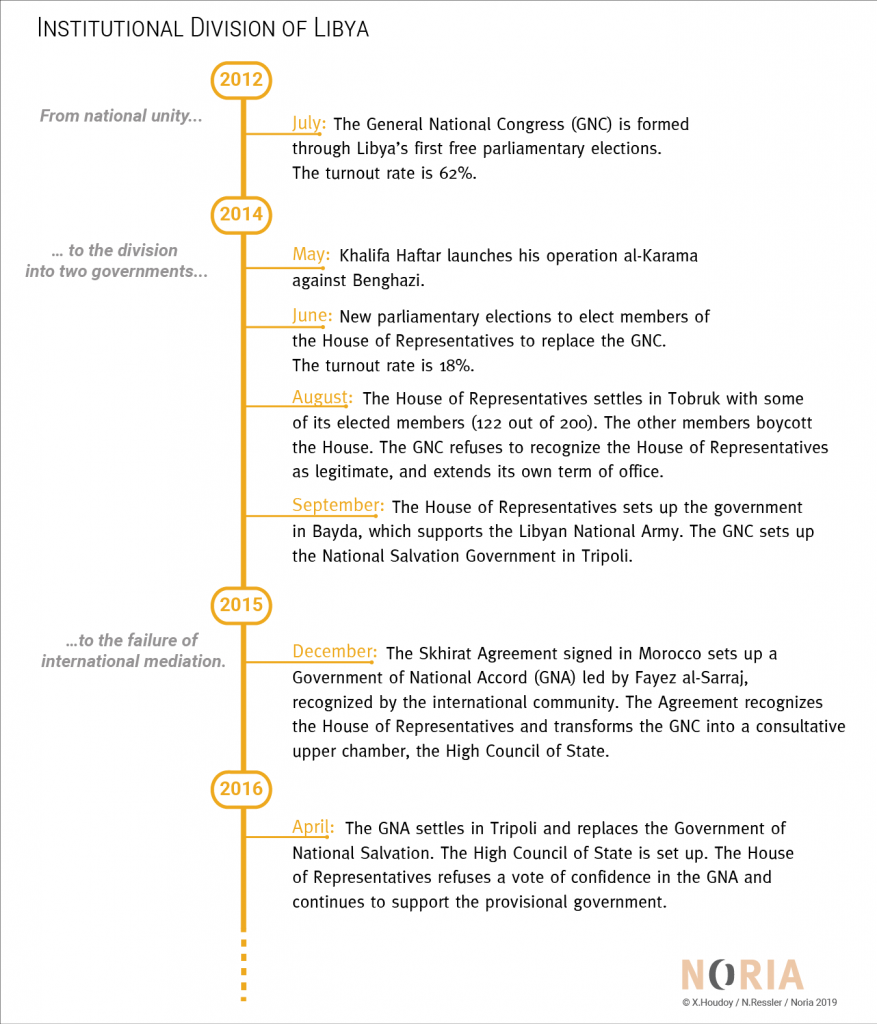

The CGN, the first elected parliament in Libya, was inaugurated on August 8, 2012 and had eighteen months to draft a constitution, which it failed to do. In the midst of the political crisis and the armed clashes, the CGN organized new elections in June 2014, which had to lead to the creation of the House of Representatives.2

With a turnout of less than 20%, the 2014 elections suffered from the political climate and the launching of the al-Karama military operation in Benghazi. The newly elected House of Representatives was very divided, and actually never sat in full session. While the Constitutional declaration stated that the Parliament was to sit in Benghazi, the House of Representatives held its first session in Tobruk (East) because of the conflicts. It was boycotted by 51 of the 200 elected deputies.

The parliament of Tobruk named an interim governement based in Baida (East). The CGN refused to recognize the legitimacy of the new Parliament and maintained its support for the Government of National Salvation in Tripoli. This was the beginning of the institutional division in Libya.

The various Libyan factions met a year and a half later in Skhirat (Morocco), under the supervision of the United Nations, to conclude a political agreement in order to put an end to the division.3 The agreement provided for the formation of a Government of National Unity (GNU) and a Presidential Council led by Fayez el-Sarraj based in Tripoli, while it also recognized the legitimacy of the House of Representatives in the exercise of legislative power. Members of the National General Congress joined the High State Council, an advisory institution created by the Skhirat Agreements.

However, this political balancing act, which placed the executive power in Tripoli and the legislature in Tobruk, while excluding some of the Libyan political figures, crystallized the division more than solving it. It is in this context that the project of the National Conference was born.

What was the ambition of the National Conference announced for early 2019?

Shortly after his U.N. appointment as the Secretary General’s special representative in Libya, Ghassan Salame announced his plan of action on September 20, 2017. He organized his mandate around four priorities: the end of political divisions by enforcing the Skhirat Agreement, holding elections, the organization of a constitutional process, and, finally, the organization of a National Conference.

The organization of the National Conference was based on 77 public meetings4 conducted between April and July 2018. The challenge was to bring together all the factions of Libyan society to define the broad outlines of a national consensus, but also identify the disagreements around four themes: priority of local and national authorities, security and defense, distribution of resources, and the electoral process.

Since 2011, Libya has experienced multiple national or international peace initiatives. The preparation of the National Conference differed from the others in many respects. Politically, it was thought as inclusive: all Libyan political figures, as well as “ordinary citizens” were invited to participate in the identification of the problems created by the political division, as well as finding solutions.

All meetings were open in order to gather those responsible for the different powers (military, militia, tribal, municipal, etc.) before their citizens. A report was made from these meetings which is available online5 and was presented to Ghassan Salame, as well as to local authorities and diplomatic figures. The National Conference was to be held in Ghadames on April 14, 2019. It was canceled due to the military offensive against the capital launched ten days before, thus breaking the political dynamic.

Is a peace agreement still possible?

The renewal of fighting has profoundly changed the situation. The urgency is to achieve a cease-fire, which is a necessary condition but not sufficient enough to start a political process. However, the factions involved don’t have the same understanding of what a ceasefire entails. For Khalifa Haftar, it would mean maintaining his positions around Tripoli, whereas for the Government of National Unity, any agreement must involve the withdrawal of the ANL troops back on the lines set before April 4, date of the launching of the military operation against the capital.

Mistrust is at its highest level since the beginning of the division, and none of the leaders want to give the other any legitimacy by agreeing to meet. Each camp is looking for new interlocutors, but for the moment, these steps are unsuccessful. The military option has not only overtaken the political dialogue, it is also crushing it.

Any new agreement will have to be more inclusive and invite all factions to the negotiation table

In addition, both sides issued arrest warrants for the higher political figures and military hierarchy of the opposing side, thus reinforcing the difficulty to organize an official meeting. The Government of National Unity has also publicly announced its intent to appeal before the International Criminal Court to investigate accusations of war crimes against Khalifa Haftar and his troops.

Finally, if the Abu Dhabi 6 agreement was successfully negotiated between the two leaders, Haftar and Sarraj, any new agreement will have to be more inclusive and invite all factions to the negotiation table. If the factions want the negotiations to have any effect, it is also essential to bring together the countries most involved and concerned by the war in Libya: Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Italy, France, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, etc.

The offensive against the capital was a reminder of the marginalization that some cities suffered in western Libya, compared to Tripoli. For example, the political and economic exclusion of the city of Tarhouna operated by Tripoli mostly explains its support for Haftar. Moreover, the offensive not only reinforced regional divisions between Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan, but also local ones, between cities that suddenly became rivals.

Any peace agreement will necessarily have to respond to these divisions and the massive concentration of resources that have been feeding the civil war since 2014. It will be necessary to reconcile the strong demand for decentralization (already promoted by law nº 69 of 2013) and the need for national unity. Today, no political actor can hope to embody the political solution alone.

Notes

- Read his portrait by Jon Lee Anderson, “The Unraveling,” The New Yorker, February 16, 2015. The supporters of the old regime, who have long regarded Haftar as a traitor, ended up rallying to his cause because they saw a political deal which was likely to bring them back in business. ↩︎

- Held on June 25, 2014, despite the wish of some of the members of the CGN to extend their mandate. ↩︎

- December 17, 2012, see the official English version ↩︎

- They took place in 43 different communities and attracted more than 7000 participants, to which we must add 1700 completed questionnaires and 300 letters received. ↩︎

- English version ↩︎

- On February 28, 2019, Fayez el-Sarraj and Khalifa Haftar agreed on an electoral process and the need to conclude the transitional period. The agreement signed in the United Arab Emirates was not made public. ↩︎