Introduction

In most of the Global South, land is fundamentally a matter of political power. Even when urban inhabitants come to largely outnumber rural ones, as is the case in most of Latin America, land remains strongly tied to the formation of elites and their influence within the state.

The recent ‘commodity boom’ in the Global South, which – beginning in the 1990s – boosted primary sectors of the economy such as palm oil, soy farming, and mineral extraction, came to reinforce this underlying logic. Contrary to what development specialists believed a couple decades ago, nothing indicates that Latin America, Africa, or most of South Asia are moving away from an ‘extractivist’ model.

As a consequence, when political and economic contradictions result in open violence, addressing land and resource inequality is a critical component of the fight to end war and build lasting peace. In this text, I argue that addressing the intricate relationship between violence and land is – in Colombia as in many other countries in the Global South – the only reasonable path to achieving lasting peace. However, the ways in which peace building experts ordinarily address situations such as Colombia’s can actually serve to undermine this objective and limit the capacity of post-conflict transitions to deliver real structural transformations.

Addressing the intricate relationship between violence and land is – in Colombia as in many other countries in the Global South – the only reasonable path to achieving lasting peace.

Why do these interventions fail? What are the intractable challenges that they face, and how do countries end up trapped in a vicious circle of inequality and violence? My argument here, which is drawn from some of my last book’s takeaways, is that there is a fundamental contradiction between the pervasiveness of violence and the very narrow focus that peacebuilding experts generally exhibit.

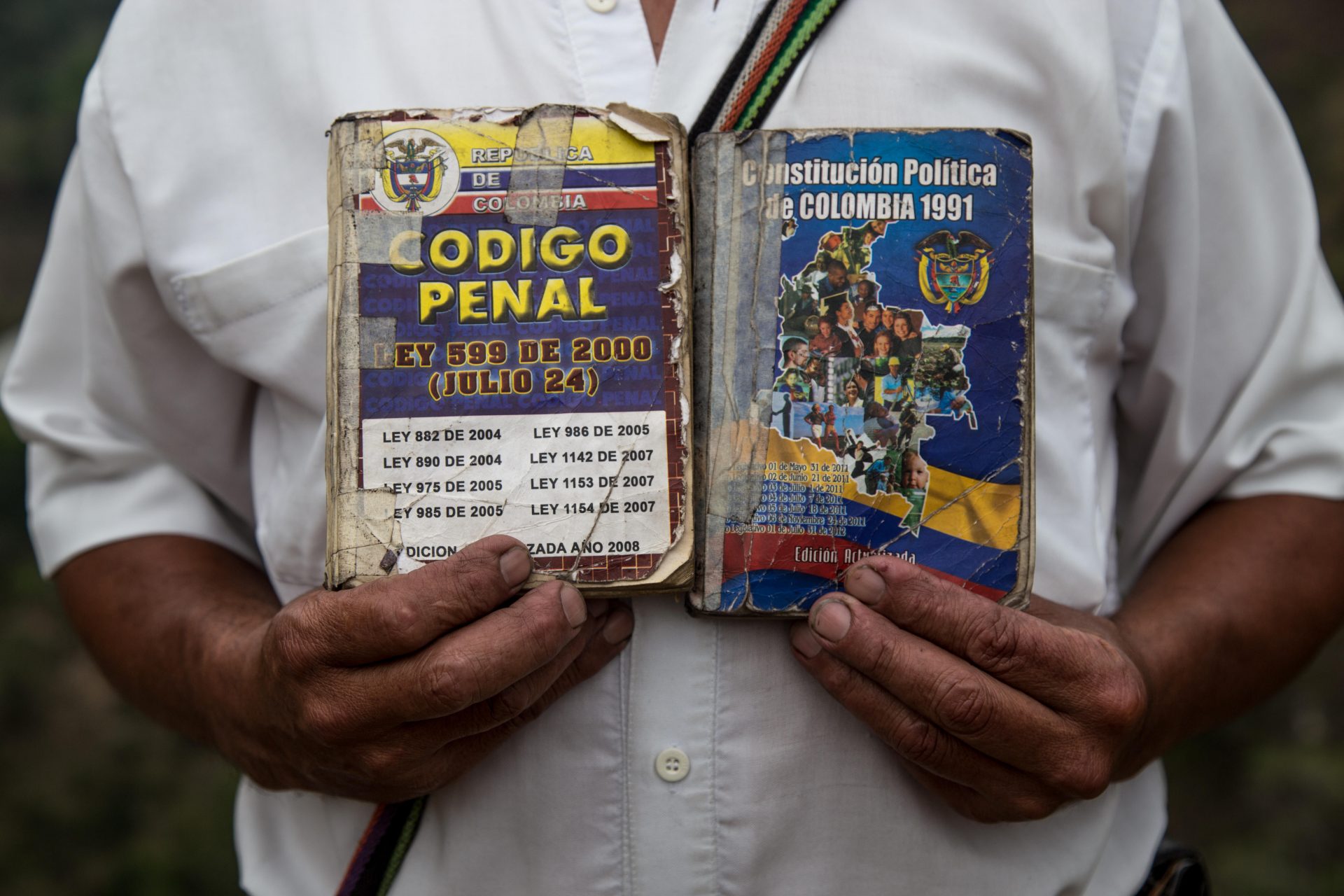

In Colombia, the formation of capitalism in intrinsically linked to a brutal history. In rural areas where landed property is highly concentrated, property owners rarely hesitated to rely on private militias to ward off claims from landless peasants. However, policies put in place to address rural property and agrarian conflicts are not designed to confront such structural challenges. The paradoxical consequence of this is that peace policies can end up concealing the close ties between plunder and lawful profit and obscuring the links between violent dispossession and the free market.

Inequality and Violence

Colombia is a textbook case of how outright inequality fuels violent conflict, how efforts to address this connection fail, and how they ultimately contribute to consolidating and legitimizing a horrendously violent breed of agrarian capitalism.

In the second half of the 20th century, extreme levels of land accumulation resulted in pervasive violence: peasant mobilisations were violently repressed by the combined strength of state security forces and armed militias hired by landowners. In many regions, this fanned the flames of resentment and frustration among peasants, leaving an open field for leftist insurgents to swell their ranks with members of the rural poor. Today, while Colombian elites strive to portray their country as a promising modern nation full of opportunities in the agribusiness and mining sectors, land remains concentrated in the hands of a select few.

In Colombia, the formation of capitalism in intrinsically linked to a brutal history.

According to the latest surveys available, just 0.2 percent of producers own estates of more than 1,000 hectares, which together encompass a total of 32.8 percent of the country’s farmland. Conversely, 69.5 percent of producers occupy plots of just 5 hectares or less. Their properties account for only 5.2 percent of the country’s available farmland.1

Colombian activists and policymakers working in the areas of peacebuilding and state-building have long strived to address the intricate ties between land and violence. In the 1960s, new land reform policies set ambitious goals with the potential to truly transform the Colombian countryside, but these were quickly undermined through the coordinated action of business and political elites. In the 1980s and early 1990s, efforts to hold peace negotiations with guerrilla groups were systematically met with violence from within the state, but also with a lack of commitment from the rebel leadership.

The eventual failure of the peace negotiations held in 1998-2002 led to a right-wing backlash embodied by two-time president Álvaro Uribe (2002-2006, 2006-2010), elected on a discourse of ‘mano dura’ (tough manner). During this time, the government dismissed all efforts to advance a rural distributive agenda, and in the 1990s and 2000s Colombia embraced an agribusiness model that gave a central role to corporate investment and large-scale agriculture. This would boost the country’s exports, attract foreign investment, and bring fortune to landed elites.

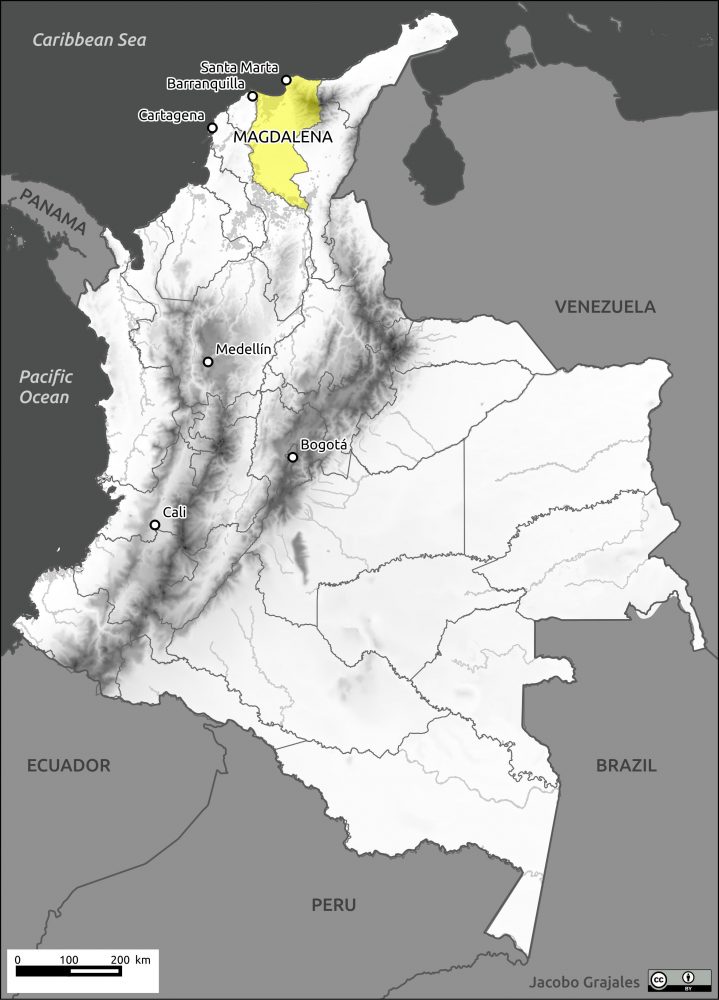

The regions that thrived due to agribusiness or extensive cattle ranching – particularly in the Northern Caribbean lowlands – became the heart of the influence and growth of right-wing paramilitary militias.

Coincidence or not, the regions that thrived due to agribusiness or extensive cattle ranching – particularly in the Northern Caribbean lowlands – became the heart of the influence and growth of right-wing paramilitary militias. According to official figures, these brutal armed groups were responsible for 59 per cent of mass murders committed during the war.2 They were not solely tasked with the protection of landed elites from guerrilla racket, as their mission went far beyond providing security. They became instrumental in the efforts of local elites to shield themselves from social protest and political challengers. In so doing, they eradicated any attempt to challenge a radically unequal social order.

Consequently, more than fighting guerrillas, paramilitary troops were busy killing peasant leaders, undoing decades of grassroots activism and community work, and annihilating the rural poor’s capacity for collective action. Murder, rape, and the gruesome desecration of their victims’ corpses became their trademark.

Gunpoint Capitalism

Since 2009, I have conducted extensive field research in one of these paramilitary strongholds: Magdalena.

An agribusiness hotspot since the end of the 19th century, when the United Fruit Company launched the development of banana-export operations in the region, Magdalena plunged into a spiral of violence from the mid-1980s with the development of paramilitary militias. This new breed of armed groups enjoyed the support of the region’s elites, who boasted both economic and political power, and they were sponsored by drug mobsters whose interests coincided with those of local patricians. In addition, they enjoyed active support from military and police forces.

These militias claimed to be a response to rebel attempts to settle in the region, but in reality were primarily organized to fight leftist civil movements and labour unions. Until the late 1980s, theirs was a selective type of violence that targeted social and political leaders. Murders became widespread beginning in the early 1990s. This corresponded to a boom in banana exports, which spurred a rapid growth in the labour force. Paramilitary militias became instrumental to controlling workers and repressing their attempts at collective action. They also enabled large landowners to accumulate land by driving peasants off their farms and using a myriad of legal schemes to legitimize plunder.

Paramilitary militias became instrumental to controlling workers and repressing their attempts at collective action. They also enabled large landowners to accumulate land by driving peasants off their farms.

In many cases, the victims of this spoliation had fought for decades to gain access to land. They came from generations of landless peasants who had struggled from the 1960s onward to force the state to redistribute rural property. Some succeeded at the cost of tremendous effort, only to be dispossessed later by paramilitary guns. Records are full of families and communities who managed to settle on their own farms after years of struggle but ultimately found themselves dispossessed by the militias and their allies. This dispossession is the embodiment of a pattern in which paramilitary violence is only the most violent manifestation of an enduring history of class wars, which are by no means limited to recent times, and – especially in a region like Magdalena – are intrinsically tied to the history of agrarian capitalism and export-oriented agriculture.

Things have changed drastically since the years in which paramilitary militias ruled over most of the Caribbean lowlands (and beyond). Between 2003 and 2006, paramilitary soldiers were partially demobilized. In 2011, ambitious land restitution legislation (the Victims Act) was enacted on the promise of reversing the effects of war, especially on rural property. The most recent episode in the country’s peacemaking efforts is the signature of a peace agreement with the FARC guerrilla group in 2016. Internationally praised by donors, multilateral organizations, and the peace community, the focus of the agreement was not confined to the FARC, as it was viewed by guerrilla groups and state negotiators alike as a comprehensive catalyst for change in Colombian society that would lay the groundwork for addressing the deep fractures that had fuelled violence for decades.

Land and agrarian issues were at the forefront of this transformative agenda. Yet, these ambitions were watered down almost before the ink had dried on the accord. A massive campaign against the agreement was launched by the conservative right, which succeeded in convincing 6.4 million Colombian voters to reject the agreement when it was submitted to a ratification referendum.

The 2016 Peace Agreement was not confined to the FARC. It was viewed by guerrilla groups and state negotiators alike as a comprehensive catalyst for change in Colombian society that would lay the groundwork for addressing the deep fractures that had fuelled violence for decades.

While the peace accord survived the backlash, the political capital of the agreement’s supporters evaporated on election night. A weary, toothless Juan Manuel Santos government failed to implement the agreement, only to be replaced in 2018 by the same right-wing factions that had promised to rip up the peace accord. Since then, President Ivan Duque, who will finish his term in 2022, has refrained from overtly abandoning the state’s commitments. However, a close look at how peace-building policies have (or have not) been implemented shows that while the agreement has not been killed, it has been left to die.

Post-War Accumulation

What does this mean for rural Colombians, and particularly for the impoverished peasants, Indigenous people, and Afro-Colombian communities who have paid the highest price in the war?

My research over the last decade has focused on former areas of paramilitary rule. Today, these regions are considered as “pacified” by both the Colombian government and most of the international peace-building community. Yet, more than actual peace, what I observe is a transformation of violent practices. Direct coercion is no longer the primary method used to push people off their land. Violent dispossession has been supplanted by less overt forms of land grabbing in which the free market now plays the role once played by threats, assassinations, and massacres.

Land and agrarian issues were at the forefront of the Peace Agreement transformative agenda.

Yet, these ambitions were watered down almost before the ink had dried on the accord.

Various factors are responsible for this situation. First, most of the large landowners and businesspeople who took advantage of paramilitary influence to grab and accumulate land in Magdalena are still running prosperous businesses. In some cases, they lost assets after a land restitution ruling determined that the property was acquired illegitimately. But land restitution processes have proved very limited in reach. As of June 2021, ten years after the Victims Act created the restitution procedure, courts have issued only 6,462 rulings nationwide. This represents a minuscule percentage of the 129,211 restitution requests submitted by victims of land grabbing. It is an even more inconsequential figure when compared to the 6.5 million internally displaced people – 87 per cent of them rural dwellers – who have fled their homes since the early 1990s. And in fact, in the agribusiness area that I studied in Magdalena, I was able to find only one case of land restitution concerning a large agribusiness estate.

One further difficulty adds to this. Even when a court ruling does recognize that violent land grabbing has taken place, such cases rarely result in criminal prosecution. Restitution orders are granted by civil courts, and there is no automatic procedure triggering a criminal investigation. Still, even in the rare cases in which such investigations end up on the desk of a criminal prosecutor, they are then handled by local prosecutors, who generally have very limited investigative resources and can easily be influenced and coerced by influential local elites.

Violent dispossession has been supplanted by less overt forms of land grabbing in which the free market now plays the role once played by threats, assassinations, and massacres.

Today, even in these unfavourable circumstances, family farmers and peasant communities still struggle to return to or remain on their lands. However, they face strenuous social, economic, and ecological conditions, as many regions of the Caribbean lowlands have been transformed by the combined impact of paramilitary land grabbing and agribusiness development. Peasants who want to go back to farming find themselves surrounded by plantations. Community life, a fundamental condition for thriving peasant economies, has been decimated by years of paramilitary violence. Lastly, most of the agricultural development policies deployed by the state are primarily designed to benefit large producers.

Additionally, natural resources such as swamps and forests (used for hunting and gathering firewood) were often privatized during the war and its aftermath. In northern Magdalena, for instance, where wetlands were critical to ensuring the subsistence of small farmers who survived by fishing and farming the fertile riverbanks during the dry season, these forms of living have been destroyed in the last two decades. Although the Magdalena wetlands are protected by an international environmental treaty (the Ramsar Convention), many swamps have been drained to create open fields for the development of banana and palm plantations.

Peasants are now selling their land – not because they are driven away from it through violence, but because the economic and ecological conditions of the region have pushed them out.

These are the trying conditions now faced by many of the peasants who managed to stay on their lands throughout the war or were able to return more recently. They explain a phenomenon that I observed during my field research, in which many peasants are now selling their land – not because they are driven away from it through violence, but because the economic and ecological conditions of the region have pushed them out. Most of them do not even have the impression that they are being dispossessed, and consider themselves lucky to be able to sell their lands to agribusiness investors. Of course, this conceals the fact that these investors are precisely the people responsible for the economic and ecological transformations that push peasants to sell.

How to Deal with Land?

This crisis is disheartening for many NGO practitioners and public officials (both Colombian and foreign) working in the field of peacebuilding.

However, most of the people I interviewed agree that peace professionals’ job is not to address the fundamental contradictions of the Colombian countryside. Instead, they tend to consider that their mission consists of addressing the direct consequences of war by enabling people to regain control over their property or to be compensated for its loss, as well as putting an end to war economies based on smuggling and racketeering in order to build the foundations of economic recovery.

The analysis built by the peacebuilding community remains highly misleading.

It obscures the fact that, in post-war times, power relations that were previously produced and reproduced in violent ways tend to be laundered and made respectable.

The reasons for this narrow focus are fairly obvious. Making a clear-cut distinction between legitimate and plundered assets helps peace professionals to circumscribe a field of action by drawing a neat line between the economic problems that can be addressed (property restitution, criminal justice) and those that are beyond the scope of any development or humanitarian assistance effort. Of course, most people I met in the field are relatively conscious of the fact that narrowing the target of peace building is overly simplistic, but they still embrace this attitude as a necessary illusion that renders their everyday work possible in a system plagued by daunting inequality.

This vision is often simply the consequence of a combination of good will and operational constraints, yet it remains highly misleading, obscuring the fact that, in post-war times, power relations that were previously produced and reproduced in violent ways tend to be laundered and made respectable. In a certain way, this view belies the close ties between plunder and lawful profit and obscures the continuity between violent dispossession and the free market. For in reality, the issues faced by the Colombian countryside are not solely a matter of justice: they are a matter of power, of the people who now control power and will control it in the years to come.

Over the last century, power in every form, from institutional influence to brute force, has been harnessed to protect a highly exclusionary social order. This has implied the violent elimination of dissent and the repression of progressive alternatives. Nothing indicates that Colombia is moving away from this political climate. As the government widely advertises agribusiness development opportunities and champions massive investment into the primary sector, the power of those who control land and other natural resources is probably larger than ever.

As such, addressing the intricate relationship between violence and agrarian capitalism is not only a historical and memorial duty, it is – in Colombia as just about everywhere else in Latin America and the Global South – a fundamental step towards the establishment of a more democratic social contract.

Jacobo Grajales’ Latest Book precisely covers and analyzes these issues.

Discover more work by the author

Grajales, J. 2021. Agrarian Capitalism, War and Peace in Colombia: Beyond Dispossession. London: Routledge.

Grajales, J. 2020. A Land Full of Opportunities? Agrarian Frontiers, Policy Narratives and the Political Economy of Peace in Colombia. Third World Quarterly, 47(7), 1141–60.

Grajales, J. 2016. Violence Entrepreneurs, Law and Authority in Colombia. Development and Change, 47(6), 1294–315.

The Photos presented in this article belong to Tomas Ayuso.