For about ten years, there have been various forms of protest in Sudan, what are the mobilization practices and who are the protesters?

Clément Deshayes: The protest against the regime is not new; it has existed since the coup d’état of 1989, but has been accentuated during the last decade. To understand the current revolutionary period, it is therefore necessary to record it within a long history of forms of resistance and protest against the regime by multiple actors, ranging from resistance committees in neighborhoods to political parties, as well as to associations and student unions.

The open protest grew between 2010 and 2011. These years mark a period of reconfiguration of the regime, but also a mounting of the opposition forces. Omar El Beshir was re-elected in 2010 after a campaign where all the opposition candidates withdrew little by little. The same year, the separation of South Sudan became evident since the leadership of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), largely dominant in the southern regions, was openly campaigning for independence. This evidence materialized in 2011 during the referendum of self-determination. The growing uprisings in the Arab nations, which the Sudanese followed closely, especially in Egypt, and the disastrous economic effects of the separation of South Sudan, detonated the reconfiguration of Sudanese political forces. This reconfiguration began in 2005-2006.

Despite the war in Darfur, peace between the regime and the SPLM, as well as the Eastern Front later on, partly meant the end of the use of political violence for a global regime change. Political parties came out of hiding in the 2000s and also abandoned the 1990s military options after the Naivasha peace agreement in 2005.1 The separation of the South meant the end of an alternative political project to the current military-Islamist regime, which was based on the idea of the New Sudan developed by John Garang de Mabior, leader of the SPLM before his death in 2005.

“These new movements, which embodied a critique of Sudanese political parties, still current in the revolutionary movement today, were major players in the protest against the regime during the first half of the 2010s.”

From then on, the protest against the regime evolved and changed little by little. During the 2010 campaign, a new group was created, called the Girifna, “We’re fed up,” which rallied to vote against the National Congress Party, the party in power. This group first took the shape of a campaign and then very quickly turned into a decentralized movement of resistance and protest which articulated street actions with intensive use of new technologies. New political movements quickly joined this group, composed mostly of students and various political and associative activists, such as sharara (spark) or al taghyr alan (change now).2

These movements, in connection with the student unions and associations, as well as some resistance groups and committees in provinces, became major players in the opposition to the regime. They began to campaign, to make public speeches, to organize neighborhood rallies and went door-to-door to raise awareness among their neighbors.

Present mainly in urban areas, these new political movements were organized more flexibly and horizontally than political parties, and challenged the regime in the streets. These activists, often students, were characterized by their creative, innovative and determined way of taking to the streets. These new movements, which embodied a critique of Sudanese political parties, still current in the revolutionary movement today, were major players in the protest against the regime during the first half of the 2010s.

In January 2011, in response to events in Tunisia and Egypt and answering the call of these new groups in particular demonstrations took place in Khartoum. These demonstrations, which were unorganized, were quickly repressed and contained by the security forces. The end of 2011 is marked by significant student mobilizations.

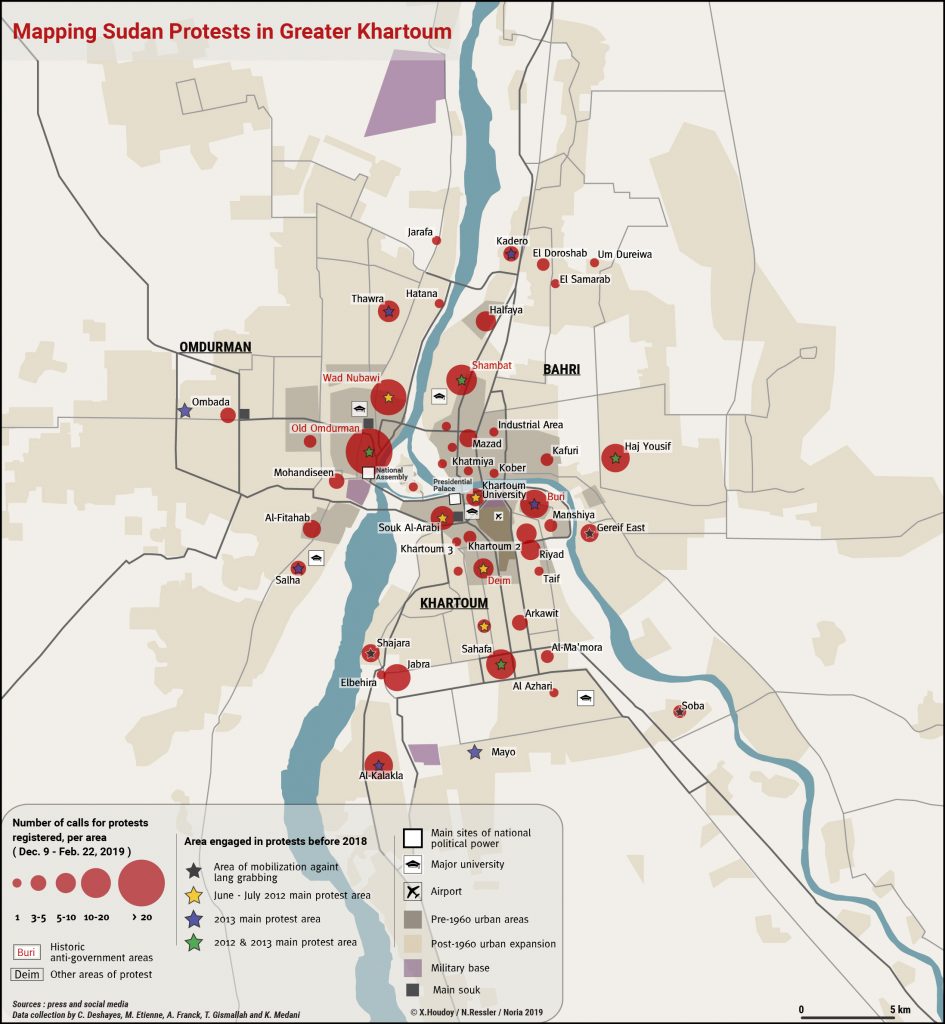

In June and July 2012, important protests also took place. The different new movements and student organizations called for revolt. These demonstrations affected many parts of Khartoum, mainly the central and university districts …

They started from the University of Khartoum before spreading in the city like wildfire. The movement rapidly grew after the police entered women’s dormitories in Khartoum University to arrest young students on strike who were already protesting against the liberalisation policies and the various austerity measures taken by the state.

In response to this police action, and echoing the demands, students went on strike in many universities, and demonstrations took place in different cities of the country. Again, the crackdown is strong, but not deadly, with the exception of Darfur in Nyala, where 12 protesters were killed. At least 2,000 people were reportedly arrested by security forces during these demonstrations.

What about the events of September 2013?

From September 23 to 30, 2013, there was a new important protest movement, and, this time, it spread to different classes and social categories. The students mobilized, now including high school students, young men, and workers, who massively took to the streets. In fact, even if neighborhoods in the center of Khartoum mobilized, the novelty came more from the involvement of residents of the peripheral districts. The inhabitants of more marginalized neighborhoods took to the street significantly, especially in the neighborhoods and districts of Umbadda, Hajj Youssef and Mayo. These neighborhoods or districts of the greater Khartoum are inhabited by people who tend to come from the west, mostly from Darfur and the south of the country.

Of course, many other districts of greater Khartoum also mobilized, such as Shajara, Burri, Thowra, Deim, Sahafa and several districts of old Omdurman, but these are neighborhoods which are traditionally hostile to the regime and mobilize more regularly.

The 2013 revolt began in Wad Madani, a provincial town close to the capital, and spread to Khartoum and the rest of the country the next day. The trigger was the general increase in living expenses, especially the price of gasoline. Yet very quickly, slogans hostile to the regime rose, and these far exceeded the question of living expenses. The economic issue was intimately intertwined with this revolt, but it was not the only determing factor.

From the outset, these demonstrations were insurrectional in Khartoum and in other cities of the country. If the regime initially seemed surprised by the extent of the protest, it nevertheless reacted in a brutal way: the internet was shut down, schools were closed, and above all, members of the party’s militia and police forces of the NISS (National Intelligence and Security Services), the very powerful Sudanese security services, were mobilized to suppress the movement. The Sudanese Medical Committee estimated that the death toll was nearly 200 people for all demonstrations. Moreover, we observed that the repression was very uneven in the city: the highest concentration of victims was in the peripheral districts.

“These ten years of protest, of experimenting and learning, enable us to think about the current movement.”

The 2013 violent crackdown put a stop to street protests and insurgency attempts for a certain number of years. Sudanese activists from different origins and groups reorganized and thought of ways to continue the fight without endangering the protesters. In 2015, campaigns to boycott the presidential election met with relative success: the regime was forced to extend the voting period because it could not reach the 50% participation target.

In November and December 2016, large general strikes were organized by the activists of asian medani and they called for civil disobedience. Their success was relative. The three days of civil disobedience in November (27-28-29) followed severe hospital protest movements and strikes by pharmacists due to the lack of medical facilities and rising drug prices. The call was clear, and essentially said: stay home, do not go to work, but do not go to protest either, the regime can’t kill you if you don’t go out. This ability to change the forms of mobilization in order to highjack the repression and challenge the regime is quite remarkable.

These ten years of protest, of experimenting and learning, enable us to think about the current movement. Given the geography of the mobilized areas, we can see that those mobilized today are essentially the same as those of 2011, 2012 and, to a lesser extent, 2013. The rapid and simultaneous spread of protests in many areas may be explained by the fact that other mobilizations occurred in the provincial cities and the various districts of the capital in recent years. For example, cities were affected by protests related to gold mining, drinking water cuts, land problems, or even privatizations, and all these have been spearheading the protests.

It is very likely that this decade of intensifying protests, at national and local levels, simultaneously allowed practices of resistance and struggle to spread, as well as to convey representations related to the injustice of the regime’s domination. Like other social processes, this probably allowed new possibilities for some of the protesters. Moreover, even without being able to draw the clear line of events, for the time being, we can nevertheless say that the slogans and modes of action of the protesters sometimes recall, in striking ways, the modes of action of the movements from the beginning of the Girifna era, in an urban environment.

In current demonstrations, we heard a lot about the presence of “young people” and students? What is the place of student movements in the protests in Sudan?

Historically, the university is a central place for struggle and protest in Sudan. The University of Khartoum, because of its history, its centrality and its responsibility in the training of political and economic elites, is a highly politicized and politicizing place.

When the Islamic movement seized power with the help of segments of the army in 1989, Sudanese universities witnessed very important clashes between the coalition of opponents and Islamist students – the former questioned the relative domination of Islamist students on campuses since the second half of the 1970s. These clashes took place in an institutionalized manner, in the context of a struggle to control the University Student Unions, a type of student office in public universities, which is in charge of the organization of social and cultural activities on campuses, and which functions as student representatives in discussions with the administrations.

In order to understand the level of violence on the campuses, we need to imagine that, since the power takeover in 1989, the student unions connected to the regime integrated the security forces in a more or less assumed way. Students from these unions needed to go the Jihad in the South and built what they called “jihadist units” on campuses.

In the 2000s, according to student activists from the opposition, the number of Islamist students decreased, new student associations were created, and dying movements, such as the Congress of Independent Students, were reborn and became major student forces.

Therefore, political activity is very important in universities, and many strikes and movements took place in recent years.3 General protests were held to counter forms of privatization, the liberalization of universities, or to protest against the poor living conditions in student dormitories as well as the general price increases. The actions of regional student associations in Darfur were very powerful, particularly in demanding the exemption from registration fees stipulated by the Doha peace agreements. This mobilization is articulated by a struggle against discrimination and efforts to convey awareness about the conflict in Darfur.

We must remember that the Sudanese regime, which focused its project on re-founding society, dove into ambitious higher education reforms. The programs were Arabized and designed in accordance with the Islamic vision of the new regime. Between 1989 and the beginning of 2010, the number of universities increased exponentially, from 4 public universities to about 30 today, including the creation of 19 regional universities. The number of universities and private colleges increased from 1 to 73 in 2016. In private universities, political activities were forbidden, but in public universities, there were associative and union activities, including those of the opposition, even when they were confined to secrecy.

Public speeches were made in the alleys of universities, there were elections, campaigns, and the situation was often quite violent. If the context changed in the 2000s, when political parties came out of hiding, the clashes remained very intense: regularly there were victims, fights with Molotov cocktails, knives, etc. Most of the violence came from pro-regime student groups who attacked rallies, public speeches, and events organized by the opponents.

How is the repression organized? In what ways has it changed since the beginning of the Revolution?

The repression evolved since the beginning of the movement in light of what the regime did in the past, even if there are remarkable continuities … The elements I will develop here do not concern war zones, which are subject to violence and control tactics that are not always comparable to what is happening in the rest of the country.

Generally speaking, before December 2018, we could distinguish several types of repression which overlapped. There was direct repression, which was violent with torture by the security forces, the suppression of demonstrations, forced disappearances, rapes, etc. This repression mainly affected the most prominent activists. But a number of activists and supporters were not necessarily targeted by these methods of repression by the Sudanese state.

The crackdown was carried out by the security services, the NISS, which contained a fairly large and extensive network of informants. It also worked more or less in line with lejna sha’abia (popular committees)4 and Islamic student groups in universities. This forceful, brutal and direct repression affected political activists, however not systematically, and not in the same way for everyone since it varied according to family prestige, social class, or geographical origin. Generally, if a person was from Darfur or the Nuba Mountains, this person was more at risk than a person from the North or the Center.

“The Sudanese state alternates between targeted repression during a certain lapse of time and on specific people, and more undefined violence as we saw during the repression of 2013.”

Sudanese services had lists of people to arrest in case of protests. These lists were updated following the protest movements of January 2011 and June-July 2012. And today, whenever there is the slightest movement of unrest, they arrest the people who are registered on this list. This is what happened in January 2018, during the demonstrations against the increase in the price of bread.

The security services arrested several hundred leaders and political activists from all parties and movements, and imprisoned them for about two to six months. This unpredictable form of repression maintains a sense of insecurity. Sometimes, an activist can speak in public without being arrested or disturbed, while at other times, a person may suffer from the wrath of the intelligence services for actions that may seem insignificant.

Today, the repression is weaker and less systematic than in the 1990s. The Sudanese state alternates between targeted repression during a certain lapse of time and on specific people, and more undefined violence as we saw during the repression of 2013.

When an activist is listed as an opponent, he no longer has access to jobs in the public administration. Companies connected to the Islamist movement are closed to these persons. These forms of repression are commonplace and their objective is to dissuade people from protesting. Trials for fake or political reasons are common, as was the case for the student Asim Omer. Asim Omer’s case is a case book – he was accused of killing a policeman during a protest and sentenced to death, but many activists are prosecuted for a various number of reasons.

Another form of repression rests in particular on the Laws of Public Order, which regulate the public area according to religious norms. These laws have been a mean of controlling the population and delegitimizing the protesters. They significantly reduce access to public areas for women, but also enable condemnation of people for behavior described as “immoral” or “indecent”. For instance, one type of repression consists of shaving the heads of people arrested during demonstrations (a practice which has become more frequent in recent years).

Finally, another repressive practice is to use social and family means of pressure. Many families are called and harassed by the security services. They threaten the families, telling them about their children’s illegal and / or “immoral” behavior, hoping that the relatives will then put pressure on them. This is especially the case for women. Sometimes, members of popular committees, local residents who are part of the National Congress Party, or more rarely, family members related to the regime, are sent to discuss with their parents. But this form of repression relies on social and family control to prevent recurring protests.

Since December 2018, these forms of repression have begun to stagger. Some of the political and protest leaders knew they would potentially be arrested, so they went underground or left the country. Some of them were still arrested as time went by. But the extent of the mobilization, geographically and in time, have overwhelmed the security forces, who couldn’t always deal with protesters in an effective way.

In fact, the board members of the Association of Professionals remained widely anonymous and clandestine during the four months of demonstrations. The leaders of this group know that the security services systematically attempt to decapitate the organized political forces each time they emerge and are able to take the lead in an extensive popular movement. For example, experienced political activists were arrested and security forces sometimes took up to two weeks to process and identify them.

However, during the current movement, the repression was not just an anecdotal fact; the security forces resurrected the famous “ghost houses” of the 1990s, real torture houses where only the cries of the prisoners escaped from within the walls. But certain images or stories, such as those of the prisoners of the women’s prison in Omdurman who continued to chant revolutionary songs, have progressively tarnished the image of an all-powerful repressive apparatus. Another novelty: local residents have begun to identify and sometimes put pressure on people identified as active participants in the regime.

Finally, if repressive methods adapt to the protest practices, they also influence the ways of mobilizing and resisting. It is not a coincidence if resistance practices have developed over the last ten years in neighborhoods, which are more secure areas of mutual acquaintance and enable one to retreat rapidly to one’s home as well as to adapt to the security force’s methods of deployment. The little dirt roads inside the neighborhoods are often obstructed by small barricades or trees that limit pursuits by pick-ups and regime militiamen. Moreover, in many places today the revolutionary neighborhood committees are the heirs of the committees created back in 2012 and 2013.

But the contrary is also true since the state has established means of controlling the social networks. NISS created cyber units called jihadist cyber units which are specialized in creating fake Facebook or Twitter accounts. For example, they created fake events to trap people and arrest them. Generally speaking, these units also served as tools for propaganda. Progressively, activists also learned to use safer channels and this is what we can observe with the Association of Sudanese Professionals (SPA). This group created an application and a website, and launched calls to demonstrate which were broadcasted quickly and securely.

Therefore, the security apparatus is overwhelmed when facing these other forms of mobilization. It also doesn’t have the means of repression since many of the street protesters are not regular or experienced political activists. Demonstrations continue despite the arrest of the later.

Notes

- In 1990, following the coup d’état, the main opposition forces (Ummah Party, Sudanese Communist Party, Democratic Unionist Party, Ba’ath etc.) formed the National Democratic Alliance (ADN). It then makes an alliance with the SPLM in 1995 and favors the armed struggle. The Ummah party left the alliance in 1999 and ADN signed an agreement in 2005 following peace agreements signed by the SPLM with the government. ↩︎

- Non-exhaustive list. Other movements were born during this period, most remarkably in Gedaref, the Khalass movement, “that’s enough,” or the street artist performance group Shawarya in Khartoum. ↩︎

- Clément Deshayes, 2018, Lutter et contester en ville au Soudan (2009-2018),note de l’observatoire de l’Afrique de l’est. ↩︎

- Popular committees are the smallest administrative unit in Sudan. The members of the popular committees, who are supposed to represent the local population, are often affiliated with the National Congress Party and are close to the regime or are awaiting resources. The popular committees play a role in the distribution of certain services or goods (especially of sugar in the 1970s) and they actively participate in the territorial police network. ↩︎