The results of the Indian national elections1, announced on May 16th of this year, were qualified as “historical” by many commentators. The victory of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, the Indian People’s Party) is without doubt historical, as under the leadership of Narendra Modi it has taken the absolute majority of seats in the Parliament. It has thus become the leading party at the national level, in front of the Congress Party, representing a major event in the Indian political life. Indeed, these elections constitute a new stage in the progressive shrinking of the importance of the Congress on the Indian political scene. After being the dominant party, from independence to 1977, the Congress had become the main national party, and then the leader of the “United Progressive Alliance” coalition that had won the national elections of 2004 and 2009. Today however, the Congress does not even have enough elected members of Parliament to call itself leader of the opposition, while the turn-out of the BJP demonstrates that coalition governments are not foregone.

This article looks back at another ‘historical’ event that has characterized these elections, namely the role taken by a party created eighteen months earlier, led by new-comers in politics, and disposing of only small financial means: the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) or “Common Man Party”. Although the AAP only obtained 4 out of 453 seats, its trajectory reveals a new mobility in the defining lines of India’s political scene – whether it is the border between social movements and political parties, mobilizing themes, styles of mobilization or even the meaning of the vote.

A Highly Visible Party

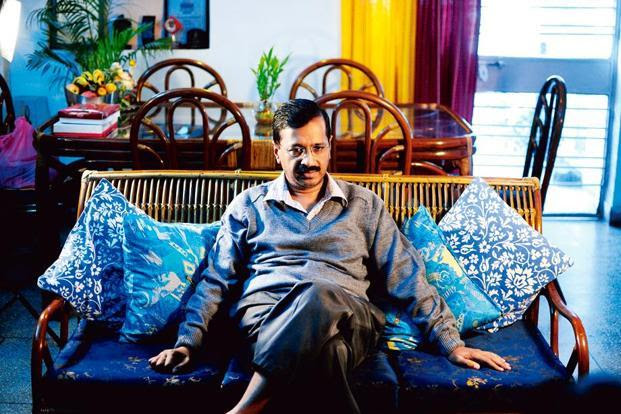

During the election campaign, the AAP occupied 10% of the prime time television coverage; three times less, admittedly, than the BJP (which was considered as the most likely winner), but twice as much as the Congress2. The written press also devoted many articles to it. This disproportionate visibility, considering its supposed political weight (the highest ratings actually gave the party 10 seats), stemmed from the continued media craze linked to the completely unexpected victory of the AAP at the December 2013 elections in the state of Delhi. From that time on, Arvind Kejriwal, the president of the AAP, became one of the most up-and-coming personalities of the Indian political scene, whether in the traditional or social media.

Kejriwal was admittedly not unknown before this date. This engineer turned public servant and later activist had received in 2006 the Ramon Magsaysay prize, often qualified as the “Asian Nobel prize”, for his fight against corruption and his commitment to the campaign for the Right to information3. Five years later, in 2011, Kejriwal came back to centre stage with the so-called “India Against Corruption” movement (IAC). He brought to Delhi Anna Hazare, an old Gandhian activist known mostly in Maharashtra and who would become the face of the IAC movement. The movement demanded the establishment of a powerful agency to fight the corruption of public servants, elected officials, ministers and judges; the Jan Lokpal. This led to an unprecedented mobilization of the urban middle and upper classes, which was largely supported by the media. A long fight with the Indian government ensued, punctuated by hunger strikes, mass protests and temporary incarcerations. The fight ended in a subdued fashion: from the original demands of the IAC movement, the Lokpal bill that was finally taken to Parliament4 was quite watered down.

In November 2012, Arvind Kejriwal and a group of faithful supporters created the AAP, arguing that entering the political game from the inside to “cleanse” it constituted the only efficient way to fight political corruption. The symbol chosen by the party is a broom, and its slogan is “India needs a revolution”. Kejriwal later had a falling out with Hazare who considered entering politics a dishonest compromise.

Not even a year later in December 2013, the AAP, to general astonishment, won 28 of Delhi’s Legislative Assembly 70 seats. It was thus positioned right behind the BJP, but far ahead of the Congress, after an election marked by an exceptional participation rate of 67%5. This unexpected success stemmed in large part from the AAP’s election campaign, which was made in a new fashion. Constrained by the lack of funds (the party was financed by member donations), the AAP has reinvented the door-to-door technique: its activists took the time to visit each family to discuss issues, collect phone numbers and email addresses. The party thus massively used text messaging, Facebook and Twitter. It mobilized the flotilla of Delhi auto-rickshaws (victims of police corruption on a regular basis), which were transformed into moving billboards. The sociological analysis of the vote reveals another surprise: while it was perceived as the party of the urban elite, the AAP has in practice also attracted the votes of the popular classes, the slum dwellers, the dalits. In other words, it gathered the traditional electorate of the Congress, except for the Muslim voters 6.

Once the results were known, the BJP refused to form a minority government. Having denounced during the entire campaign the corruption of the other two parties in the run, the AAP also refused to form a coalition government with the Congress. To escape this dilemma, the party innovated once more by launching a large consultation of the electors through an online referendum and a series of meetings, the jan sabha, in all the constituencies. When the largely positive result of this consultation came out, the party decided to form a government with the support of the eight elected members of the Congress, and Arvind Kejriwal became Chief Minister of Delhi. The AAP would only end up staying in power 49 days, but during the first weeks it seemed to re-enchant politics. The government struggled to implement its participative credo (by being very present in the streets), and multiplied spectacular decisions (such as the provision of free access to water and a drastic reduction in electricity prices for small consumers, or the creation of an “anti-corruption branch” that filed several complaints for corruption against ministers and industry leaders). However, it rapidly gave the impression of rushing things too much, being amateurs, incoherent in their discourse and their actions. Arvind Kejriwal quit the job when the adoption of his emblematic bill, the Jan Lokpal, seemed compromised for both procedural and political reasons. The AAP was thus free to fully commit to the election campaign for the Lok Sabha, India’s lower chamber of Parliament.

The Party of “Organized Defiance”

Pierre Rosanvallon’s expression of “organized defiance” adequately resumes what distinguishes the AAP from other Indian parties, whether in its origins, in its project or in its intervention modalities. The origins of the AAP, as we have seen above, can be traced back to the anti-corruption movement, the national campaign for the right to information, but also, further back, to the action of the NGO founded by Kejriwal in 2002, Parivartan, dedicated to the fight against corruption in the city of Delhi. These different types of mobilization embody the “counter-democracy” as defined by Rosanvallon; that is to say the appropriation, by civil society, of “powers of control and surveillance”7 over those who govern.

Indeed, these powers are at the core of the AAP’s project, as it appears in the book published by Kejriwal in 2012, Swaraj8, in the Constitution of the party, or in its “Vision”9. The party endeavours to fight against corruption, nepotism and crony capitalism of connivance, to promote the right to recall and to confer important powers to the local assemblies (gram sabha in the villages, mohalla sabha in the cities). The AAP thus aims at giving to citizens the power to keep under surveillance, to control, to inspect but also to reject, when needed, those who govern and their actions.

Finally, the challenge also characterizes the type of intervention that the AAP promotes in the public debate: relentlessly asking upsetting questions, denouncing, accusing, without stopping, without fear, and often without nuance, the most visible politicians, the heads of corporations but also famous journalists10.

These three aspects – its origins, its project and its intervention style – are precisely the party’s strong points. Its origin – organized civil society – enables it to access a large pool of activists who are both experienced and highly motivated, and among whom many young people can be found (students, graduates, unemployed). Its main project, the fight against corruption, allows it to reach all the electors and to transcend class, cast, gender and religion barriers. Finally, its style enables it to occupy a considerable space in the media. To this sensationalist aspect of the challenge can be added a highly developed sense of political communication as well as a true mastery of social media11 that offer traditional media an abundant and easy to use source of material.

The AAP’s Campaign Gambles

The strong media presence of the AAP during the spring 2014 election campaign can be explained both by this talent for political communication and by the idea that the party could, this time again, have unexpected results. It can also be explained by its political boldness that pushed it to present candidates in 434 of the 543 constituencies, that is more than the BJP and the Congress (which respectively presented 415 and 414 candidates). This decision seems even bolder as the party started with two major handicaps: there was not enough time to create structures outside of Delhi, and its budget was minimal12. The AAP’s ambition was thus evidently to use these elections as an accelerator of political growth.

When the results were broadcasted on May 16th, the electoral christening at the national level rapidly unravelled: only 4 candidates were elected, moreover, in locations where they were not expected (in the state of Punjab where the AAP gathered 24% of votes). None of the star candidates of the party (Arvind Kejriwal in Varanasi, Medha Patkar in Mumbai and Yogendra Yadav in Gurgaon) were elected. In Delhi, the party won 33% of the votes. This was a better result than in December (it had then won 30% of the votes) but remained insufficient against the BJP that won all the capital’s seats. At the national level, the AAP gathered only 2% of votes, which half what its leaders hoped for.

A retrospective overview of the campaign and the analysis of the percentage of votes obtained in some key constituencies enables us to map out the AAP’s three successes and the three challenges it failed to meet.

Firstly, the AAP managed to occupy the media space in the entire country, by presenting itself as the first obstacle against the announced “wave” in favour of Modi. Arvind Kejriwal had chosen to present his candidacy in Varanasi to defy the leader of the BJP there. He had been present, early on in the campaign, in the state of Gujarat which Modi had led as Chief Minister since 2001. He had continuously denounced the key messages of his rival that portrayed Gujarat as a “model” state in terms of growth and governance. Finally, he accused Modi of financing his campaign using big industrial groups, and thus of being corrupt.

Secondly, the AAP was able to impose its core themes in the public debate, be it was the fight against corruption and criminality in politics, the issue of financing election campaigns or the allegiance of media to economic powers. Again, this success was limited to the domain of the debate as, in the end, the percentage of elected MPs, who face criminal charges has grown continuously (34% today against 24% in 2004). Furthermore, the cost of Narendra Modi’s campaign was unprecedented and two weeks after the elections, the largest Indian private group, Reliance (led by Mukesh Ambani), took control of the largest media group Network 1813.

The AAP also inspired its competitors regarding some aspects of its political style: challenging one’s opponents; developing a strong local base and promoting participative democracy. Indeed, the BJP also had to adopt a more dynamic electoral strategy. Thus it went to challenge its rival on his own field (Modi campaigned against Rahul Gandhi in his constituency of Amethi), started developing local (and not only regional or national) spheres of online sympathizers and multiplied smaller campaign meetings with questions and answers (called “chai pe charcha”) alongside larger electoral gatherings. By contrast, the campaign run by the Congress seemed old fashioned, an aspect that could have contributed to its defeat. The posters that showed a thoughtful Rahul Gandhi, in black and white, did not help rejuvenate the image of the party and its attempts to occupy the social networks mostly revealed the Congress team’s gaps in political communication techniques.

With regards to the failed challenges, the first one was the ambition of the AAP to be the party of change14, and notably to change the rules of the electoral game. Facing the ostentatious austerity of the AAP, Modi deployed unprecedented means. As always during electoral campaigns, politics became a show, and the contrast between the AAP’s processions and the ones of the BJP in Varanasi were striking; the more Kejriwal demonstrated his normality, the more Modi spoke of his privileged relationships with the divine15. Confronted with the “common man” party, the BJP promoted the almost superhuman quality of its candidate.

Another failed objective consisted in becoming a national party (which implied gathering at least 6% of votes in at least four of the Indian Union states). However, as we have seen, the AAP managed decent results only in Delhi and in Punjab. Moreover, the symbolic victories on which it was counting by presenting core party members against the leaders of the BJP and the Congress, did not materialize. Although the failure of Kejriwal in Varanasi was honourable, Kumar Vishwas’ failure against Rahul Gandhi in Amethi was striking.

The third failure is the worst for the future of the AAP. The analysis of the vote demonstrated that the party did not manage to develop the very heterogeneous support that had made its victory in Delhi possible. As the Delhi results show, but also the ones from Mumbai or Bangalore, the middle and upper urban classes seem to have remained loyal to the BJP, for which they constitute a traditional support base. Beyond the Modi effect, which is obvious, this result questions the ideological blur that has characterized the AAP from the start. Indeed, the party claims a pragmatic approach to the country’s issues, at times risking over-simplification: “I want to fix problems; I don’t understand right or left” has declared Kejriwal in the past16. The reference to Gandhi, but most importantly to Jaya Prakash Narayan, which feeds the discourse and political style of the AAP is a double-edged sword. Jaya Prakash Narayan, a Gandhian leader, called for a “total revolution” in the early 1970s to fight against corruption in Indira Gandhi’s government. Imprisoned during the state of Emergency declared by her in 1975, he became the spiritual leader of the first non-congressional government, formed by the Janara Party in 1977, a party made of all the opponents to Indira Gandhi, from the Hindu right to the communist Left, and which rapidly fell apart under the weight of its contradictions. The AAP too is characterized by the large political heterogeneity of its members, as it includes disappointed former supporters of both the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) and of the BJP17. The analysis of the profiles of the AAP party candidates reveals that the most important group was made up of activists committed to a variety of causes, ranging from the fight against corruption and the right to information to the rights of tribal populations, of dalits and of peasants, and that liberal professionals such as lawyers, doctors and engineers made up the second group. The risk is thus important, for the AAP today as for the Janata Party yesterday, not to hold together all of the activists who are motivated by highly diverging visions of the role of the State in the Indian economy and society.

The Party Of Rejection?

The results of the May 16th poll in Delhi gives the opportunity for a comparison with the December elections and suggest, retrospectively, a new explanation to the AAP’s success at that moment. The “anti-incumbency” factor certainly played a strong role against Sheila Dixit, the Chief Minister who had led the Congress to victory three times in 1998, 2003, and 2008, and the opposition from the BJP was rather bland. It however appears today that beyond the benefits linked to its outsider status, the AAP could have benefited from a vote not for its proposals, but for its indignations, that is a rejection vote. Indeed, it is easier to identify what the AAP is opposing rather than what it is pushing for. The AAP is the “anti” party: anti-corruption, anti-nepotism, anti crony-capitalism and also anti-communalism.

This interpretation is reinforced by the fact that the number of votes in favour of the AAP is sometimes close to the number of NOTA (“None Of The Above”) or blanked votes18, which were counted for the first time at the national level during the April-May 2014 elections. Even if, on the scale of the Indian Union, the AAP vote is twice as important as the blank vote (which concerns only 1.1% of votes), it would seem that the presence of the party in the campaign, alongside the new possibility of a blank vote, has diverted towards this rejection vote a number of votes that would otherwise have been for the Congress, and thus has contributed to making this election a turning point in Indian political life.

The AAP leaves this electoral trial weakened. On the media scene, it has been eclipsed by the striking victory of Narendra Modi. On an internal level, it is confronted by a strong expression of dissatisfaction from the activists who criticize the lack of internal democracy, by conflicts between leaders and by the resignation of several eminent members. The party is now struggling to recover what made it strong in December 2013: it is undergoing an internal reorganization in order to make more space for the grassroots volunteers and has decided to concentrate all its resources on the upcoming legislative assembly elections in Delhi. Arvind Kejriwal has apologized to the inhabitants of Delhi for his “mistake” in resigning last February. The AAP is thus trying to reinvent itself into the party of an alternative urban governance: more participative, more in favour of the poor, more centred on essential services. The party’s elected representatives multiply the “mohalla sabha”, which constitute a first attempt to create a participative budget in the Indian capital. Even though it has become much less visible, the AAP remains nevertheless a party that might bring change, at the level of the capital if not at the national level.

Notes

- The ballot took place in nine phases, between April 7th and May 12th 2014. ↩︎

- “Modi got most prime time coverage”, The Hindu, May 8, 2014. ↩︎

- In 2005, this campaign led to the adoption of the Right to information at the national level (see http://righttoinformation.gov.in/webactrti.htm ). ↩︎

- The Lokpal Bill would be adopted at the national level in December 2013. ↩︎

- During the previous elections in Delhi, in 2008, the participation rate was 57%. ↩︎

- “2013 Legislative Assembly Elections, Delhi”, Economic and Political Weekly, February 8, 2014, pp. 82-85. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- The term « swaraj » (« self-government » in Hindi) clearly refers to the Mahatma Gandhi and to his famous essay Hind Swaraj (Indian Home Rule, 1909). This reference evokes two major Gandhian ideas of A. Kejriwal and the AAP: on the one hand, that India has to commit to a new fight to give the power back to the Indian people (power which was taken away, in the context of the 2010s, by corrupt elected officials and bureaucrats and by corporations which are accountable to no-one); and on the other hand, that decentralization is the best way to attain these goals. ↩︎

- See http://www.aamaadmiparty.org/our-vision ↩︎

- For example, in March 2014, A. Kejriwal accused “a section of the media” of selling a positive media coverage to the political parties – without making the effort to specify which newspapers or television channels were targeted, and without bringing any proof (“Parties paying media: Kejriwal“, The Hindu, March 15, 2014). ↩︎

- The AAP has a cell dedicated to social media, which has a great autonomy and mobilizes around 250 activists, most of them being young graduates of the ICT sector. ↩︎

- The election campaign budget of the AAP was estimated to 350 million rupees, while the law authorizes 7 million rupees per candidate and the actual expenses are estimated to be 10 times this figure. ↩︎

- GuhaThakurta, Paranjoy (2014), “What Future for the Media in India?”, Economic and Political Weekly, June 21, pp.12-14. ↩︎

- Roy, Srirupa( (2014), “Being the Change. The Aam Aadmi Party and the Politics of the Extraordinary in Indian Democracy”, Economic and Political Weekly, April 12, pp. 45-54. ↩︎

- “I have been chosen by God: Modi”, The Hindu, April 24, 2014. ↩︎

- “A promise betrayed”, The Hindu, January 25, 2014. ↩︎

- Among the 7 AAP candidates in Mumbai, there was both Medha Patkar (leader of a slum dwellers defense movement and incarnation of the austerity activism opposing neoliberalism) and Meer Sanyal (Former high-profile banker, member of the Confederation of Indian Industries). ↩︎

- Notably in the states of Chhattisgarh and Karnataka. ↩︎