In August 2019, Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government removed the constitutionally mandated autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir, the only Muslim-majority state in India. The decision is analyzed in the wake of N. Modi’s triumphant reelection to the office of Prime Minister in May 2019, after a first term which started in 2014. Through the example of Jammu and Kashmir, this article aims to account for the larger socio-political dynamics at work in India that allowed Modi’s government to stay in power despite poor economic results. Last but not least, this paper will try to understand the establishment of a new Hindu political hegemony relying on the government’s centralized and authoritarian power. All of this represents a break with the regime that India chose for itself at Independence.

In May 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s second government was concluding its first year in office. One year before, under Modi’s leadership, the Hindu Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People’s Party, BJP) was reelected after a first term that started in 2014. Although its economic results fell short of 2014 campaign promises, BJP won even more seats at the Lok Sabha, the Parliament’s lower house, going from 282 to 303 out of 543.

This increase in the number of seats can lead us to assume growing support for the BJP’s ideological program and the Prime Minister’s wielding of power, mostly among Hindus, the party’s main electoral target. Indeed, the party advocates for an ethnic conception of citizenship, according to which the Hindu demographic majority (80% of the population) is considered as a homogenous community, conceived as a group united by common socio-political interests. It stems from this conception of the social body that Hindus are considered as the only legitimate political body, since, as their religion is seen as the only indigenous one, they are the sole “sons of the soil” in India. By contrast, the Muslim and Christian minorities (14% and 2% of the population respectively) are suspected of civic and moral disloyalty because of their supposedly alien ethnic groups and religions. As illegitimate citizens, they must bend to the interests of what is declared to be the majoritarian community, the Hindus. N. Modi’s government is also defined by its authoritarianism and centralized decision-making and implementation, running counter to the Republic’s federal system and usual practice in Indian institutions.

Such was the context when, in August 2019, Jammu-and-Kashmir’s (J&K) constitutional autonomy was abrogated. The decision was made by the Minister of Home Affairs Amit Shah, and it was critical for this state bordering Pakistan, which has 12.5 million inhabitants, 7 million of which live in the mostly (Sunni) Muslim Indian Kashmir valley. Beside the situation in J&K itself, the way this change of status was implemented perfectly reflects – among other implications – the two main characteristics that define N. Modi’s government. This analysis will aim to underscore these two characteristics by focusing on the mechanisms that led to the restructuring of J&K’s political class. In order to better understand them, this paper will also analyze these trends with reference to the national political reactions that followed the decision and the silencing of the J&K’s population by the government.

From State to Union Territory: Central Government Increased Control over J&K

On August 5th, 2019, the institutional framework of the Indian Republic was deeply altered by the abrogation of J&K’s constitutional autonomy. Jammu and Kashmir went from being a state constituted of three regions (Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir), to being divided into two administrative units: on the one hand, Jammu-and-Kashmir, a new Union Territory with an elected assembly; and on the other hand, Ladakh, a Union Territory without an elected assembly. This reform was carried out through the revocation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution guaranteeing J&K its special status. As a ripple effect, Article 35-A, which granted privileges such as property rights as well as access to public sector jobs to Kashmiri natives in the Kashmir part of the state, also became void.

Those articles had taken effect with the implementation of the Constitution in 1953 and they laid the basis for the integration of J&K to the Union. Indeed, J&K is a demographically unique area in India since it is the only Muslim-majority state, and historically special too, as it was divided between India and Pakistan after the two countries’ first conflict in 1947, in the wake of the British decolonization. Articles 370 and 35-A established J&K’s political and cultural autonomy, even as they preserved the demographic balance that existed at the time of independence. However, that autonomy was relentlessly curtailed by New Delhi’s successive central governments, with the support of some local parties. Besides, those attacks on Article 370 went hand in hand with increasingly strict “security” policies. Indeed, the central government always presented restrictions on freedom as necessary to ensure the safety of the national territory, by protecting it from the neighboring enemy, Pakistan, and from the forays of foreign fighters, coming from Islamabad to wage jihad in Indian Kashmir.

The security-driven policy in the area has been enforced at the expense of Kashmiri citizens’ rights and freedoms, as illustrated by two laws: the Jammu-and-Kashmir Public Safety Act (JKPSA), which has allowed the detention of Kashmiris without formal charges and without trial since 1978, and the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), implemented in September 1990, officially in order to quell the uprising started by separatists in the Indian Kashmir Valley in 19891. Armed violence had erupted after the 1987 elections were rigged by New Delhi, with the support of the local section of Congress party, in order to lower the high number of votes expected for separatist parties advocating for J&K’s independence from the rest of India. The AFSPA granted considerable power to the 500,000 soldiers and 100,000 civil and military intelligence officers deployed by the central government in Kashmir.

Security-driven Policy

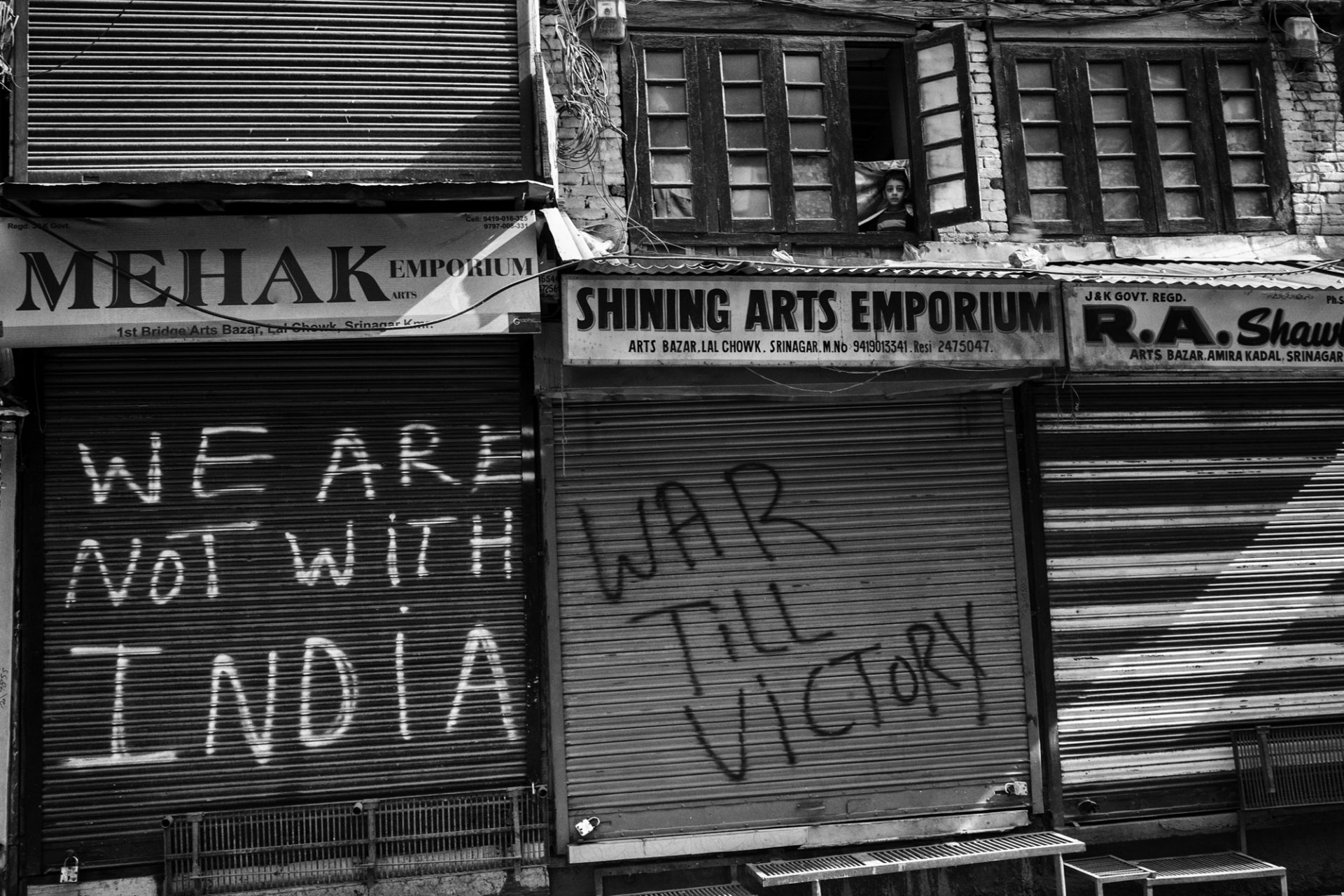

Ever since those laws came into force, the armed and police forces operating under them have benefitted from a substantial degree of legal immunity, committing a vast number of crimes (rapes, torture, murders, forced disappearances, collective punishments, etc.2) The security-driven policy failed to quell the armed uprising in Kashmir, but it did fuel a growing feeling of national disaffiliation among the Kashmiri population. As the locals experience the Indian state exclusively through its ‘right hand’, they look at the central government as an occupying power.

This brief historical overview shows that J&K’s autonomy had already been largely challenged on the groundcompared to what was stated in the 1953 Constitution. However, Article 370 still existed and the Kashmiri people often claimed its full respect as a basis for their political claims against New Delhi. Moreover, Article 35-A was designed to be the ultimate protection of J&K’s unique identity, by ensuring the preservation of the state’s demographic balance. Hence, the removal of both articles doesn’t merely enshrine a pre-existing situation, but it is an actual institutional, social and political upheaval for J&K’s population – and beyond, for the Indian institutional framework itself.

Shrinking Autonomy

Jammu and Kashmir was India’s most autonomous state, as it had its own Prime Minister (instead of a Chief Minister) until 1965, as well as its own constitution, flag, and penal code. When Articles 370 and 35-A were revoked, J&K lost its special status and was relegated to a lower level of autonomy than the other 28 states. Indeed, the other states are administered by elected representatives forming a government, headed by a Chief Minister, and have their own assemblies. They also have Governors who are appointed by the President of India to represent him (and the central government) and who elect representatives to the higher and lower houses of Parliament. Finally, they have the right to promulgate their own laws, according to the distribution between central and local powers stated in the Constitution.

In August 2019, J&K was stripped of this status and divided into two units. On the one hand, Ladakh is now a Union Territory directly administered by a Governor who is appointed by the central government to represent the President of India. Ladakh now sends only one representative to the lower house. On the other hand, J&K is also a Union Territory, but it has the right to elect its own assembly, to have its own government and to send elected representatives to both houses. However, elections still haven’t been held in J&K, which has been under the central government’s direct rule since 2018. The central authorities argue that elections haven’t been held because of the region’s instability – thereby contradicting their own version of the story since the repeal of Article 370 was presented as a way to put an end to social unrest in the valley.

It is safe to assume that the prerogatives of the future J&K’s government will be highly limited by virtue of its new institutional status. In the meantime, New Delhi recently enacted the removal of Article 35-A. Since April 1st 2020, access to property and jobs has been granted to people having resided in J&K for fifteen years or having studied there for seven years. Similarly, more than a hundred texts have been amended to revoke Kashmiri natives’ special rights.

A Centralized, Top-Down Decision

The decision to abrogate Articles 370 and 35-A was unilaterally implemented by the central government, without any discussions with its partners in the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) coalition, even though the repeal does away with the historical modalities of J&K’s integration to the Union of India. Moreover, local political forces weren’t consulted in the process, even “legitimist” groups who don’t object to J&K’s integration with India, such as the National Conference (NC), the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), the local Congress section and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)). Contrary to the separatist parties of the Hurryiat Conference (HC), those parties are considered legitimate by New Delhi and have successively administered J&K since Independence. But not only were those parties not consulted, they were silenced along with all active political parties in J&K after A. Shah’s announcement.

As early as August 5th, all the main local leaders, including former BJP allies, were placed under house arrest or even jailed. Among the people arrested were for instance Farooq Abdullah and his son Omar Abdullah. The former is the son of Sheikh Abdullah, a tutelary figure of Kashmiri political life and the founder of the NC. Farooq Abdullah has headed the NC since 2009 and has also been J&K’s Chief Minister three times between 1980 and 2000. As for Omar Abdullah, he was Chief Minister from 2009 to 2015, and Minister of External Affairs in the first BJP government (1999-2004).

Another prominent figure of the legitimist political group to be arrested was Mehbooba Mufti, the latest Chief Minister, who ruled over J&K from 2016 to 2018 at the head of a coalition government with BJP which won the 2014 elections in Jammu. Mehbooba Mufti had succeeded to her father, Mufti Muhammed Sayed, who died in office in 2016, and who had also been a major figure of Kashmiri political life since the 1970s.

Invisiblization

Just like their leaders, political activists were arrested en masse. The centralized authoritarian power exerted by the government is also illustrated by coercive measures against the Kashmiri society as a whole, betraying a refusal to take citizens into consideration. Along with the violence used by armed forces against protesters, the imposition of a curfew, the increased number of police controls, and the blackout of any type of communication (cell phones, landlines, and internet) for several months amounted to a sentence in an open-air prison for J&K’s inhabitants. They were the ones who were most affected by J&K’s change of status, and yet they were unable to express themselves. In some towns, the roads were not reopened until early 2020. At the end of August 2020, only 2G internet services have been restored in J&K, even though 4G is available in the rest of the country. Communications are restricted by this poor coverage.

More than a year after the abrogation of the special status, the lack of consideration for the local population is still patent. The government has now begun a policy that deliberately turns Kashmir’s cultural and historical heritage invisible. For instance, two days were dropped by New Delhi from the official list of holidays: Sheikh Abdullah’s birthday on December 5th and “Martyr’s Day” on July 13th, which commemorates a protest that was harshly suppressed in 1931. But a new day was added to the list: the day when J&K officially joined India, October 26th (1947). Similarly, the Sher-i-Kashmir (Kashmir’s Lion) International Conference Centre in Srinagar, which was named after the title attributed to Sheikh Abdullah, was renamed Kashmir International Conference Centre in early March.

Finally, school textbooks have been revised. Since March 2020, they have included the change in status, without explaining, however, how the decision was actually enforced (legal procedure, communications blackout, numerous arrests). Moreover, the recent change in property rights fuels longstanding fears of a demographic replacement among Kashmiris in the valley. On the ground, all these decisions are seen as expressing the desire to make J&K’s Kashmiri Muslim population “disappear” in order to exploit the land, which is rich in agricultural resources and hydropower, and is also a famous tourist site. Far from improving the integration of the local population to the national community, the measures only feed into the popular feeling of disaffiliation from the Indian state.

In New Delhi, Authoritarian Government and Silent Opposition

The scrapping of Article 370 didn’t come as a surprise, since it had always been at the heart of the BJP’s Hindu nationalist political program. It is in line with the centralized conception of power favored by the nationalists, particularly for a territory where the majority of inhabitants are Muslim and therefore considered as illegitimate. Besides, the abrogation was one of the key arguments in the BJP’s campaign in 2019: the party presented the measure as a necessity for national security after the attack on an army convoy in Pulwama, J&K3.

However, the way the decision was made was highly authoritarian, which challenges its validity under traditional institutional practices. A. Shah took advantage of the “President’s rule” (direct rule exerted by the central government) over J&K since June 20184 to have the President abrogate Article 370, thereby avoiding the necessary legal ratification by the Kashmiri assembly called for in the Constitution. As the BJP won a substantial majority at the 2019 elections, it is no surprise that the removal of Article 370 was largely supported by the members of the NDA coalition, nor is it surprising that there was no objection to the manner in which this was carried out.

What is more striking is that many opposition parties also supported the measure, especially regional groups whose political latitude, and therefore their very existence, greatly relies on the Union’s federal architecture and the respect of its institutions. And those parties even adopted the government’s version of events, arguing that the insurrection was caused by J&K’s socio-economic backwardness, and that the “normalization” of the institutional situation should put an end to it. This, despite J&K figuring among the most developed states in the Union according to national indicators.

Supporters of the abrogation also failed to address the obvious contradiction between the Minister of Home Affairs’ statements, asserting that the situation in J&K is “normal”, and the fact that the state had been cut off from the world and its population kept under lockdown from August 2019 to March 2020. In the Congress party, supposedly the main national opposition party, the mild objections that were raised reflected deep ideological and structural divisions, which prevent the group from seriously standing up to the BJP. In the end, political parties merely provided a rubberstamp for the government’s discourse.

Sporadic Protests

In a context of general political apathy, the main act of contestation was to inform people about the ongoing situation. Since the local press was also affected by the communications blackout, independent English-language media from the rest of the country were the ones relaying Kashmiri voices and telling what was happening on the ground. Such articles revealed a situation starkly different from the “normalcy” described by A. Shah, who simultaneously admitted to the arrest of nearly 4,000 people in the first weeks of August. Contrary to what the Minister of Defence Rajnath Singh said, Kashmiris were far from accepting the decision, as they opposed it in various ways. Daily protests were organized in the valley after the removal of J&K’s special status. They were violently suppressed, sometimes with armed violence, as hospital records confirm, even though the Minister of Home Affairs denied it. News reports also allowed Kashmiris to express their anger, their fear of moving, their grief for the dead.

On top of documenting the situation, some media also condemned it: the harshest criticism came from independent journalists and activists expressing their views in public statements, analytical papers, and opinion articles. A group of five women activists travelled to Kashmir in September 2019 to report on human rights violations after the August 5th decision. They publicly disclosed cases of temporary or long-lasting disappearances of young men since the abrogation, estimating them at 13,000 approximately. Such arrests are generally followed by the search or even the ransacking of people’s houses. But those voices remained marginal, as they were constantly delegitimized by the central government and its supporters, who accused them of being “anti-national”.

Outside J&K, the abrogation of its constitutional autonomy provoked no major political or social protest, except in a few traditional left-wing strongholds such as universities, and more specifically the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, were voices raised. The media’s version of events largely aligned with the official discourse, notably in non-English language press and/or TV news. This friendly coverage should be understood in the light of Narendra Modi’s close personal relationships with the heads of the big industrial groups owning those media outlets. By and large, on the national scale, the abrogation of Article 370 was rather widely accepted by Indian people, and even acclaimed by some, as demonstrated by the celebrations held in the wake of the announcement by members of several Hindu nationalist movements.

In Jammu and Kashmir, Political Expediency and Popular Resistance

Opposition parties weren’t the only ones to unexpectedly support the scrapping of Article 370: some Kashmiri politicians also backed the decision. Initially, the support came from political newcomers, such as members of the All Jammu and Kashmir Panchayat Conference, of the Jammu and Kashmir Political Movement (India), and the former president of the Congress party’s Kashmiri student wing, Mir Junaid. All of them benefitted from the government’s publicly staged special favors. During the J&K blockade, the members of the All Jammu and Kashmir Panchayat Conference were invited to New Delhi by A. Shah in early September 2019, and those of the Jammu and Kashmir Political Movement were the only ones allowed to hold a press conference in Srinagar. As for Mir Junaid, he remarkably came into the media spotlight thanks to iconic TV host Arnab Goswamy, a fervent government supporter who invited him to his shows on “naya Kashmir”, “the new Kashmir”5.

A New Political Class?

The congruence of the arrival of those newcomers on the Kashmiri political scene and the decision to silence J&K’s longstanding political class leads us to consider the two phenomena together. It seems that the central government and its Kashmiri political supporters were mutually using each other. For New Delhi, co-opting or even “creating” local political figures perfectly suited the current authoritarian centralized power. The government chose J&K’s local leaders from New Delhi. This allowed the central government to mold the Kashmiri political scene into what served its interests best. As for the newcomers, the closeness to the central government presented the opportunity to build a career in a political arena that had been emptied by the imprisonment of traditional party leaders.

As a matter of fact, being anointed by the BJP seemed to be an absolute prerequisite to exist in the political field, given the control exerted by the central government on Kashmiris’ political and social lives, and more generally speaking, given the territory’s reduced autonomy from now on. In turn, making this local political class visible was also vital for the BJP. The statements made by the members of these new groups confirmed A. Shah’s version, according to which the traditional Kashmiri political class was entirely corrupted and had to be renewed. These supports strengthened the BJP’s hegemony.

What is even more significant in the long-term is that those new actors allowed the BJP first to establish a political class whose very existence depended on the central government, and second to entirely renew the political landscape by getting rid of any jarring voices. But since April 2019, this strategy seems to have reached its limit. The newcomers were excluded in favor of better-known political figures who are well established in J&K. One can assume that this turnaround is due to the absence of local political spokespersons for the new elite, and to their inability to properly administer the territory, even if they were covertly supervised by New Delhi. The figure of Mir Junaid perfectly illustrates the discrepancy between the central government’s discourse and the reality on the ground: even as he was on a media tour in New Delhi and was presented by pro-government newspapers as the embodiment of J&K’s political future, he was, and still is to this day, virtually unknown across the Kashmir valley.

Two facts attest to New Delhi’s new strategy. First, the creation of the Apni Party (“Our Party”) headed by Altaf Bukhari, former local Minister and ex-member of the People’s Democratic Party(PDP). This new party is seen by Kashmiri people as controlled by New Delhi, and that is confirmed by A. Bukhari and A. Shah’s close relationship, which is well reported in the media, although party officials deny it. Secondly, Farooq Abdullah and Omar Abdullah have been freed, in March and April 2020 respectively, whereas most political leaders remain under house arrest, such as Mehbooba Mufti and the other members of the HC. Their liberations incite observers and the population to think that Omar Abdullah will play a major role in the new J&K. Actually, since they were allowed to express themselves in public again, neither of them has mentioned Article 370. On the contrary, they tacitly endorse its abrogation since they don’t object to the August 5th decision per se, and they only bring up the restoration of the status of federal state, whereby the authority of the Chief Minister is higher than his counterpart’s in a territory. Only NGOs questioned the legality of the decision by bringing the case to the Supreme Court, but no political party has done so.

Governing the Kashmir Territory through Political Co-optation

This new strategy of co-opting well-established political figures who already have a wide network serves the same purpose as the overhaul of the local political class described before. For the central government, it is a way to administer Kashmir by using the existing political leaders who are now all the more tied to New Delhi. As for the local figures co-opted by New Delhi, they can still hold their political office and enjoy the associated political and economic rewards. As a consequence, even though A. Shah presented the August 5th decision as a way to fight against cronyism, the central government actually encouraged it and allowed it to function unchecked, just like its predecessors.

Far from becoming a “new Kashmir”, the territory is marked by the perpetuation of old practices, where the distribution of political resources by the central government buys the votes of local representatives: the indispensable varnish of democratic legitimacy applied over political decisions that are made without any local consultations. The dynamics will therefore not be different from what they have been since Independence, and mostly since the 1980s, continuously eroding the population’s trust in both the central state and the local legitimist political class. The former is seen as more interested in the territory than the wellbeing of its inhabitants, and the latter are accused of being corrupt and controlled by New Delhi. So even though the institutional framework has changed, the factors of disaffiliation remain unchanged, as the population finds itself, once again, “like an insect stuck between two elephants”, to quote a phrase that is popular among Kashmiris. They consider those political maneuvers with their usual contempt, which they disdainfully sum up with the formula “business as usual”.

Since March 2020, the fight against Covid-19 has also been used as an argument to heighten the authoritarian and violent silencing of the Kashmiri population. Since the beginning of the lockdown, nearly 2,300 Kashmiris are estimated to have been arrested, some of them have been killed, hundreds of stores have had to close down, and hundreds of vehicles have been seized. Violent arrests and physical punishments for violating the lockdown are common throughout the whole country. But they acquire special significance in a territory that had already been placed under lockdown for months and whose inhabitants have lived under a special regime for thirty years.

The government presented the abrogation as a way to better integrate J&K into the Indian Union and to restore “security” in the context of terrorist threats. But in reality, Kashmiris’ feeling of disaffiliation has been exacerbated and has spread to the populations living in Ladakh and Jammu, where protests have also been observed. In the meantime, enrollment in the insurgency hasn’t gone down. So it is now obvious that none of the government’s official objectives has been successfully reached so far.

Beyond the local effects and ideological implications entailed by the silencing and the invisiblization of the only Muslim-majority area in India, as well as the erosion of its institutions, the assertion of an increasingly centralized and authoritarian power didn’t really cause a stir in the country. On the contrary, both the decision of the abrogation and the way it was implemented were received either with passivity, or with satisfaction and enthusiasm. Those reactions reflect the desire for, or at least the acceptance of, a power rooted in an ethnic conception of citizenship whose implementation relies on the executive government’s centralized, authoritarian control, at the expense of the traditional Indian institutional functioning.

All of these elements corroborate the hypothesis presented in the introduction: that of a growing hegemony of Hindu nationalism. This hegemony is conceived in its Gramscian sense, as “universally valid” in the whole Indian society, and especially the Hindu population, which is constituted and maintained as an organic group by the Prime Minister. The massive support shown to the BJP at the 2019 spring elections materializes this hegemony as it contributes to it. But the attraction exerted by the party can no longer be limited to a single election cycle. And yet, in the wake of the citizenship laws drafted in late 2019, this new hegemony challenges the open and inclusive quality of the Indian citizenship as it was forged in 1953.

Notes

- The insurgency was started by Kashmiri fighters, who were then joined by Pakistani and other foreign fighters, including “transfuges” from the Afghan war (1979-1989). Those foreign warriors were rejected by the local population because of the crimes they committed. There were essentially two categories of fighters at the time: Kashmiris mostly asking for Kashmir’s independence; and foreign fighters who wanted Indian Kashmir to join Pakistan, and who were therefore actively supported by Islamabad. ↩︎

- See the latest report by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/PK/KashmirUpdateReport_8July2019.pdf It is worth adding that India condemned this report and considers it as an interference into Indian internal affairs (see https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-slams-un-rights-office-report-on-jk-as-continuation-of-false-narrative/articleshow/70127923.cms), and that Pakistan has also been accused of violating its own Kashmiri citizens’ rights namely those living in Gilgit Baltistan and Azad-Kashmir. ↩︎

- On February 14th 2019, a car carrying explosives was rammed into an army convoy by an Indian Kashmiri as the vehicles were passing through the district of Pulwama, south of Srinagar. 46 soldiers lost their lives, and the attacker also died in the explosion. The attack was claimed by Pakistani armed group Jaish-e-Mohammed. ↩︎

- When the BJP left the coalition government and the Chief Minister resigned, the Kashmiri assembly was dissolved and J&K was put under the direct rule of New Delhi before the next elections. ↩︎

- The use of the phrase is very clever because it is a reference to the title of a memorandum on the restructuring of J&K drafted in 1944 by Sheikh Abdullah in order to achieve emancipation from the Dogra absolute monarchy that the state was submitted to back then. ↩︎