With a population exceeding twenty million, Karachi is one of the largest cities in the world. It is also one of the most violent of these megacities. Since the mid-1980s, Karachi has endured endemic political conflict and violence, which revolve around control of the city and its resources—licit and otherwise.

A city of merchants founded by Hindu traders in the beginning of the 18th century, Karachi developed around its port, which anchored the city’s economy and polity to the oceanic trade linking India, East Africa and the Persian Gulf, but also to the turbulences of its distant hinterland. Since the early 19th century, Karachi became the gateway to Central Asia and weapons shipments and foreign combatants have been disembarking on its shore whenever the clouds of war descended upon Afghanistan.

Since the 1970s, Afghan conflicts have been spilling over the city, which was flooded with small arms, hard drugs and battle-hardened refugees. It is in this context that the city’s urban struggles started to revolve around ethnic lines, from the mid-1980s onwards, paving the way for the rise to power of the Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM).

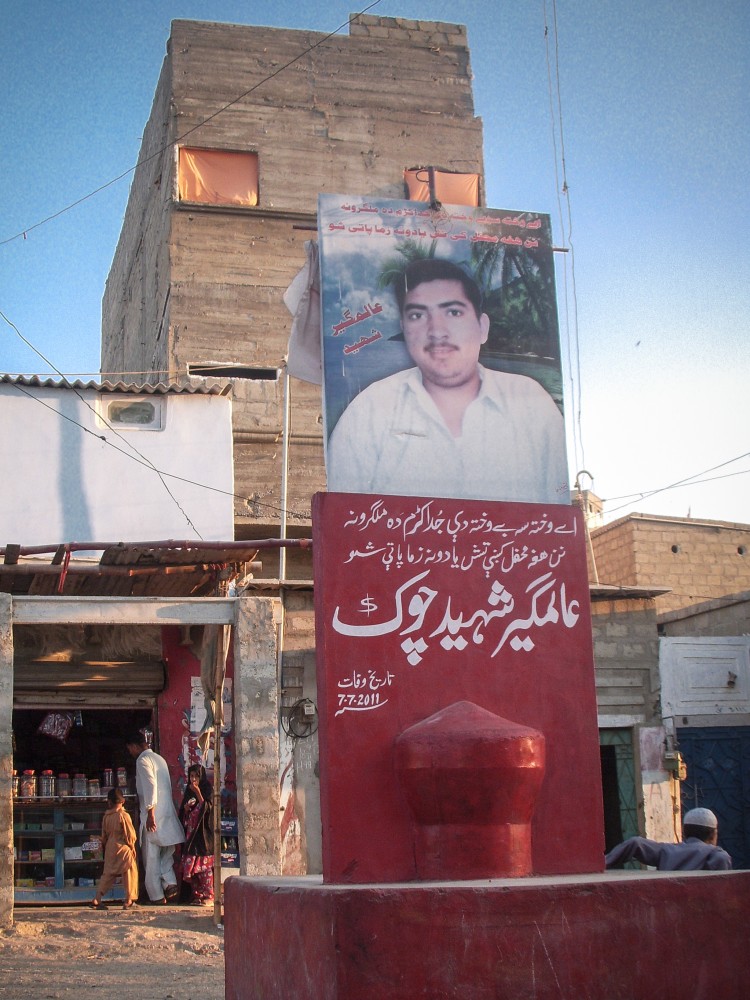

An ethnic party representing the Urdu-speaking populations that migrated from India to urban Sindh after the Partition of 1947, the MQM has adamantly sought exclusive control over “its” city. This hegemonic aspiration is manifest in the saturation of the city’s visual environment with the party’s imagery, and in particular with the ubiquitous figure of its self-exiled charismatic leader, Altaf Hussain, who has been presiding over the destiny of Karachi from London since 1992. In recent years, the MQM’s claim to “own” Karachi has been increasingly contested by new contenders to public authority, from sectarian and jihadist militants to inner-city gangsters with links to the international drugs trade.

“The primary vocation of these photographs was sociological”

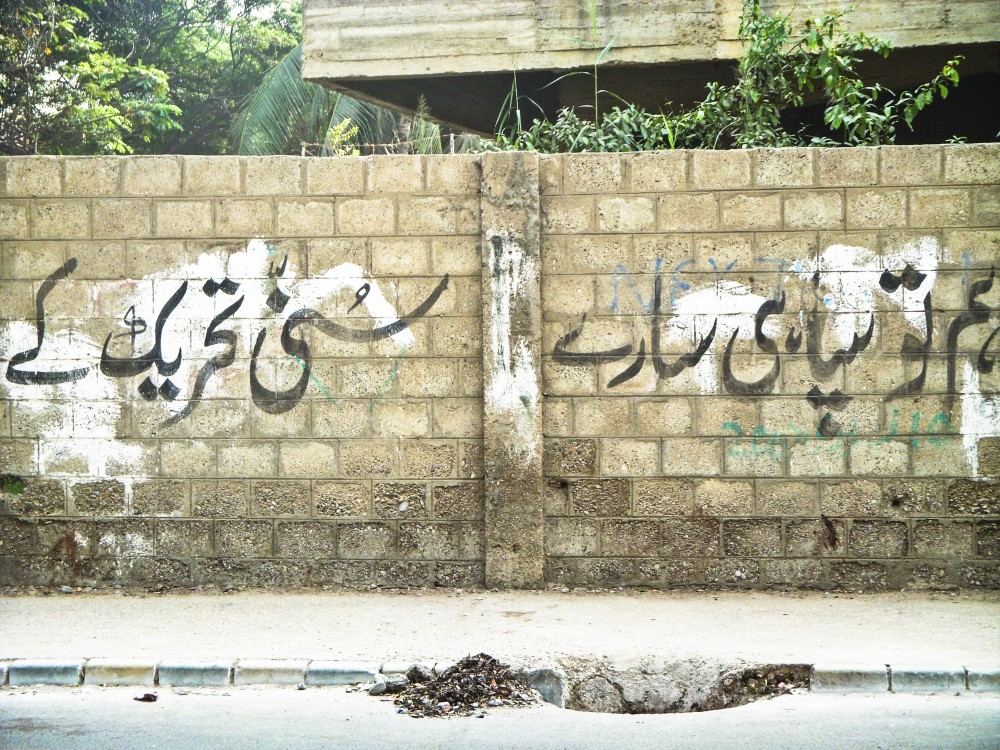

As I drove, rode and walked across the city, interviewing residents, activists or social workers from all ethnic and ideological backgrounds, from 2001 onwards, I started chronicling visually these endless conflicts by constituting my own pictorial archive of the city’s ordered disorder. For reasons of safety and comfort, I only carried a small digital camera, which fit well in the front pocket of my kamiz, allowing me to pull it out every now and then.

The camera became my other notepad, which I used to record the ubiquitous political and religious slogans adorning the walls of the city, the paraphernalia of political parties and the architecture of (in)security marking the boundaries between contested turfs. The primary vocation of these photographs was sociological: they were first and foremost research material complementing my oral and textual sources. As such, they were not always properly framed, focused or exposed. But as these images kept on piling up in my hard-drive, it became obvious that they were telling their own tale, bringing out the dead while capturing vividly the sense of dread and urgency that animates the living in this city at war with itself.