Honduran migrants who make it across the countless perils on the migrate route gravitate towards areas where they know someone from the old country who can help them get housing and work. I visited communities in the Northeastern United States, speaking both to newly arrived migrants and long term residents.

Elias leads his congregation in prayer. Elias left Honduras after his brother was killed over a land dispute. Once in the US, he went to a town in Long Island that his church had said would welcome him. A decade later he’s become a leader among the town’s Honduran diaspora. (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

A Honduran woman in prayer during Sunday services. Once Elias was settled in, members of the same congregation from chapters in El Salvador and Honduras began flocking to the Long Island town. This process by which diasporas grow is similar in Honduran communities across the United States. (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

The congregation listens to Elias’ weekly prayer for lost migrants. A church member described the difference between being a Honduran in the US and one in Honduras, “Here we are united. Over there everyone is out for themselves. Our families here work together. In Honduras you only find broken homes. We find our strength in our unity.” (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

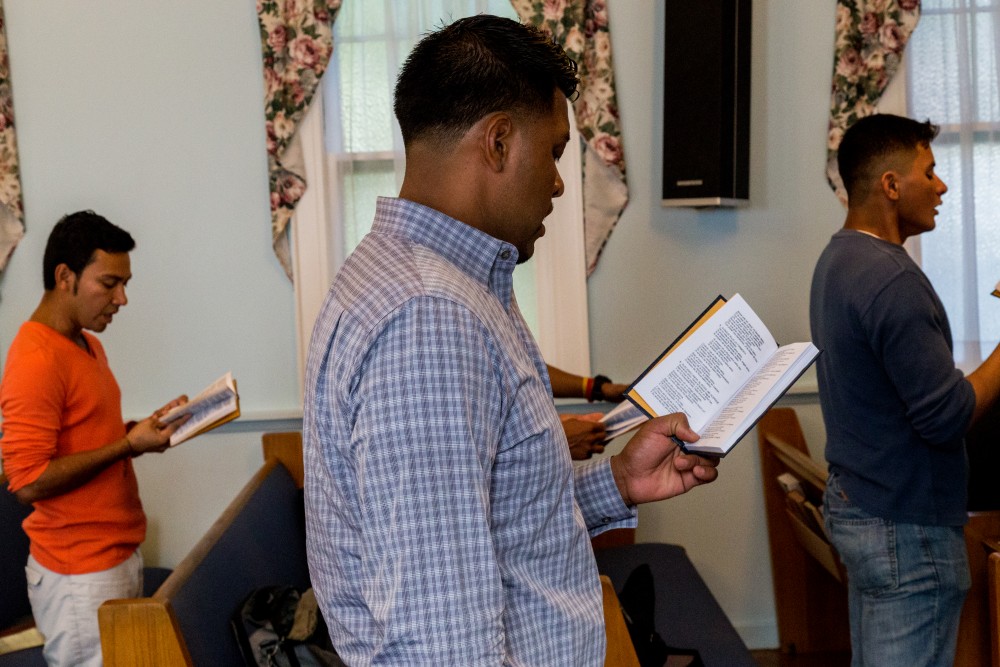

Cousins who had recently arrived from Choluteca, Honduras sing hymns during Sunday services. The recently migrated as well as residents could not help but express despair at the troubles plaguing Honduras. A naturalized citizen criticized the authorities. “Violence and criminality are an issue, but I blame the systems we as a country have created more than anything.” (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

A husband and wife from La Ceiba, Honduras listen to community announcements during Sunday services. The church Elias came into was almost without a congregation when he first arrived. Now, some ten years later, the formerly Italian church is now almost entirely Honduran. (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

In Boston, Hernan works as a sous chef at a fine dining restaurant. He still lives in the shadows due to his status as an unauthorized migrant, a fact he lamented. “We’re all human beings. We come here to work, to have a shot at a life with dignity. We deserve a chance if we live with decency. I’d be the happiest man in the world if I had papers, so I could see my family back home.” (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

Saul left by himself at the age of 12. He saved enough money to reach Mexico and traveled on top of the Bestia to the US-MEX border. He crossed into the Texan bush with a group of migrants. Feverish with infected tonsils and lacerated feet, Saul collapsed believing he was going to die. He remembers thinking, “I made it to the United States. I did my part. Let God do what he must.” Saul was later found unconscious and near death by Border Patrol. (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

“I bounced around detention centers for a few years, until I received my residency just a month ago. Had I been deported I wouldn’t have had anyone to go back to.” I caught up with Saul just as he was moving from the tri-state area to New Orleans with hopes of working in the oil industry. (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)

“You see all kinds of things on your way up here, on that train. And yes I have suffered here in this country. And I wish things had gone differently for me. I love Honduras, I love my country. I loved playing ball with no shoes on, jumping into the rivers with my brothers. But the truth is, I don’t think I was going to survive had I stayed.” I said goodbye to Saul as he got on yet another train but this time headed south as a resident of the United States. (Copyright © 2014 Tomas Ayuso – Noria Research. All rights reserved)