Can you describe the organization and mobilization of the recent protests that took place in Khartoum and other places?

Mohamed A.G. Bakhit , Sherein Ibrahim, Rania Madani : The Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) is the main organizer of the protests.

The SPA was initially composed of three bodies of professionals: the Sudanese Doctors Central Committee; the Sudanese Journalists Network; and the Democratic Lawyers Alliance. The SPA announced its official existence in August 2018 during a press conference. Their original intent was to submit to the Parliament a study about decreased income in Sudan with a list of demands after a demonstration of professionals.1

Since the beginning of these protests, the SPA has communicated through social media, providing weekly programs of protests to be held in Khartoum and other cities in Sudan, even in rural areas. This widespread use of social media and Internet as the main platforms for communication and organization of the activities is new for most of the demonstrators and surprised the security forces. They had no experience in dealing with such communications and mobilization channels. Importantly, those technologies have been mainly used by young middle-class people, based in urban areas.

Moreover, for rallies in the center area of the city or in neighborhood areas protests, the SPA organize the demonstrators by fixing the time and location for the meeting point and by providing them with slogans and themes.

The protests in the center of the city usually take place in central market area in Khartoum, in Omdurman or Bahri, or in other small markets, main streets and bus stations in suburban areas. Protesters seek to form big rallies of people coming from different parts of the city to march towards an important government institutional buildings (e.g. Presidential Palace, Parliament). Most of the participants are university students, unemployed persons, civil servants, people from private sector or self-employed people, with a real involvement of women. The majority of protesters are educated people with former professional experiences or prospects of becoming professionals (graduates).

The protests that take place in central areas of Khartoum are organized under the leadership of the SPA, opposition political parties, or some youth civil society organizations. However, other groups also participate and from them new leaders have emerged, gaining recognition through their confrontation with the security forces. This means that the issue of leadership is more dynamic and horizontal, in the sense that leaders might not necessarily be appointed from above by the SPA or other political forces, but that the leadership can emerge and evolve in a flexible manner according to the requirements of protests.

Protest leaders can decide which directions are safe, protect the people, help the injured protesters, and provide assistance tools (e.g. water, masks). They can advise protesters not to throw stones at the police, and not to cause material damages in the protest area (such actions have mostly occurred in the demonstrations that took place in the neighbourhoods protests).

During the protests, we can also observe a lot of solidarity from people not directly participating in the protests. These people could hide protesters who are chased by the police inside their buildings. Families and business organizations have helped protesters in different ways (e.g. providing shelter, food, water or medical assistance).

Were there other forms of demonstrations, other initiatives of revolt, outside the calls of the SPA and outside the central areas?

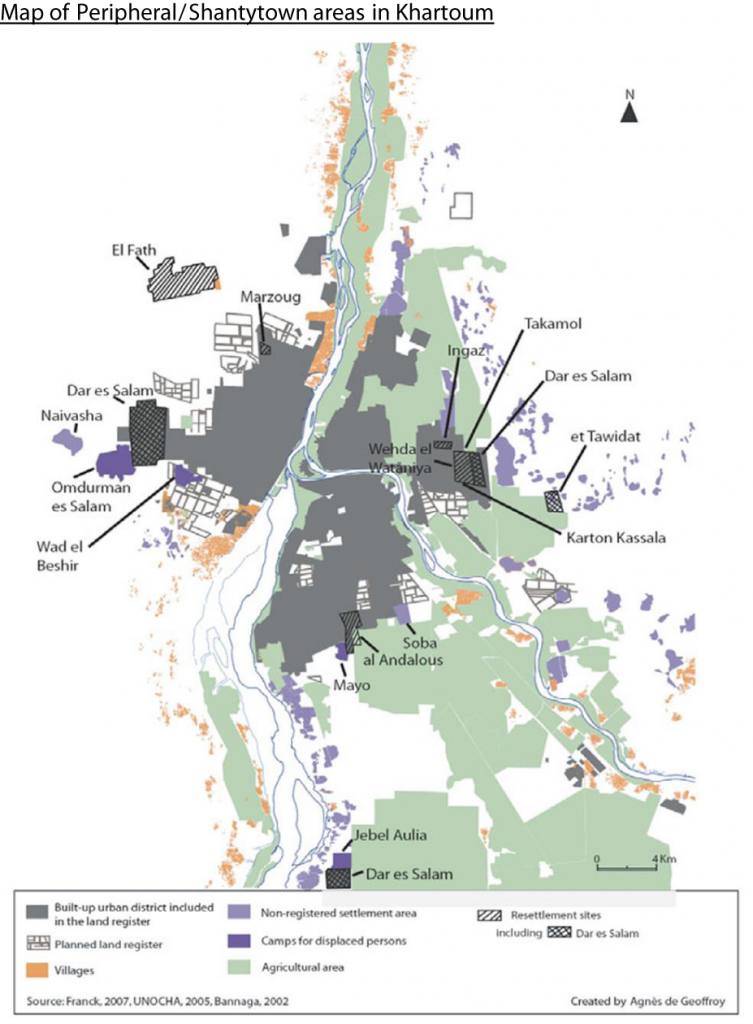

It is possible to differentiate two main categories of protests since December 2018. The first one is the one describe before, in the central areas of Khartoum. The second type is the protests enacted in the neighborhoods, both in old and planned urban areas of Khartoum2. Most of the time in old areas (e.g. Burri, old Omdurman, Shambat), with sporadic protests coming from more planned urban areas (e.g. El Sahafa, Elthora, El Mazad, El Kalakla, Haj Yousif… etc).

Those neighborhoods protests are more homogeneous in terms of participants. They are mostly comprised of youth, males and females, youngest being teenagers. Protesters usually try to build a roadblock setting tires on fire to close the roads. Some neighborhoods become well known for it, as it was almost done on a daily basis in Burri and old Omdurman areas.

The resilience of these demonstrations could then be explained by the strong and long-lasting relationships among neighbors.

In the neighborhoods protests the SPA plays a smaller role. The “local leadership” is the one that matters in these neighborhoods. Most people have known each other for a long time, family relations are well established, and there are very few new comers in these areas. The resilience of these demonstrations could then be explained by the strong and long-lasting relationships among neighbors. The brutality of the security forces also strengthened the solidarity among neighbors; as the security forces became one common enemy to all neighborhood inhabitants.

The local leaders, chosen for their experience and skills (i.e. protest management knowledge), are the ones that decide the meeting points, the direction of the march, the building of roadblocks, and that divide the roles among the participants in the protest. In this type of protest the entire family can be mobilized and play a role. For example mothers and old people might join the protest, at the beginning until the police comes, and once at home they can continue to inform protesters about police movements and open their doors to demonstrators in need of shelter.

Teenagers and children also participate despite the risks they face of being caught and abused as much as more mature participants. The protests in the neighborhoods generally turn to be more violent and fatal than the ones in central Khartoum3. Protesters can throw stones at the police and security forces can respond by using tear gas and live ammunition.

Yet, in both types of protests, we can find a huge participation of women and girls in different roles and even the risky ones. Females participate in throwing back tear gas to the police, being in the front row confronting security forces. Some have been arrested, beaten, harassed and sexually abused. During these recent protests, when security forces realized women power, they started to target them and abuse them even more. Their courage and fierce resistance might be the result of the systemic violence and discrimination endured by women in Sudan in the last 30 years.

Why peripheral urban areas are not taking part of the protests?

There is a disconnection between the peripheral areas or shantytowns and other middle-class areas in Khartoum, which led inhabitants from the former to consider the protest in central Khartoum and other middle-class areas as not their issue.

To understand the reason behind that disconnection we need to look into the history of those peripheral areas to see how urban expansion developed in the context of Khartoum urban expansion. First the majority of the population living in peripheral areas in Khartoum came to the capital as displaced people, fleeing from war, drought and desertification. For example at least 2.4 million people were affected by famine by mid-1985 in the western regions of Sudan. And around the same time, the civil war broke out in the former South Sudan region in mid-1983, displacing about 4 million people, 1.5 million of whom ended up in the capital.

The presence of a huge number of forced migrants in the capital living in largely squatter settlements was not a problem in itself, but their discrimination became one. This comes from the fact that the social/ethnic hierarchy dominant in the northern parts of Sudan establishes that people from Southern Sudan and the Nuba mountains, and to a lesser extent those from Darfur, have to be considered as having a lower status due to their different cultural features, be they religious or ethnic. The majority of people coming from these regions consider themselves as having African descent, while the majority of people in north Sudan consider themselves as having Arab or Nubian origins. For example, Ja’aliyiin, Shaygiyya, and Dangala, the main ethnic groups in the Nile Valley, have dominated the Sudanese state since the pre-colonial period, particularly since the introduction of Islam and Arabism to Sudan in the sixteenth century, accompanied by a legacy of slavery trade.

That bitter historical relationship between the peripheral population and the rest of the city has always tended to be shaped by majority-minority relations. This relationship strongly reflects the hierarchical system that dominates the country as a whole, as people from north and central Sudan have dominated the State, the economy and national culture, and have treated other parts of the country as mere peripheries. This has turned peripheral areas’ population into the most vulnerable and stigmatized people in the capital.

Moreover, most people from Darfur and Nuba Mountains remember that no single protest was organized when there were reports of mass killings and violence done by the NCP regime in their original areas. While for South Sudan refugees, their legal status remains very critical, so most of them try to be invisible to the government.

Since this disconnection is also the result of the NCP regime’s long history of mismanagement and discrimination towards peripheral areas in Khartoum, it was imperative to see how these policies managed to divide the population of Khartoum.

Indeed, if we analyze the urban policies of the government towards illegal settlements of poor people, it is clear that it has long consisted in legalizing settlements in remote areas, by re-planning or upgrading them, and in demolishing squatter settlements located near the center and in high value areas.

The planning and upgrading of squatter settlements in remote areas was not intended to change the socio-economic position of the people, but rather to consolidate and legalize their position in the city as the lowest status of people. As such these policies encouraged peripheral/shantytown residents to develop a distinct lifestyle that emphasizes and enhances their difference from the mainstream city population, by keeping stronger relationships with their home areas and maintaining traditional cultures, with minimum interactions with an urban way of life. This is encouraged by physical segregation (e.g. areas planned as Fourth Class settlements, at the periphery of the city), and socio-economic marginalization (e.g. ‘lowest’ ethnic status, low-income jobs).

Does is it mean that the current nation-wide protests in different parts of Sudan don’t make sense for the peripheral population in Khartoum?

Well, not exactly, but there is difference in how it works. For example, the economic and political crises – among other factors – that led to the nation-wide protests are actually hitting mainly the so-called middle-class areas. For example, the local currency crisis in Khartoum banks affected first and foremost the middle-class employees, and fuel shortages affected mostly car owners mostly who usually live in middle-class areas. Meanwhile the population of peripheral areas and shantytowns has faced these economic hardships for a long time, and most of them work in the informal economy with the ability to get cash money and negotiate their income on a daily basis. So the recent economic crisis was not a major upset in their life, as they already had to cope with multiple economic challenges due to previous economic deterioration. For poor people in Khartoum, it is a story they already know.

This violence has become part of their daily life and has been accompanied by racial and bureaucratic discriminations.

In addition to that, the use of extreme violence by police and security forces against shantytown populations is not new. They have actually suffered from multiple forms of brutality from the police and security forces since their arrival in Khartoum (e.g. demolitions or alcohol raids4). This violence has become part of their daily life and has been accompanied by racial and bureaucratic discriminations. Seeing heavily armed police vehicles in shantytown streets is a normal thing. There is a long experience of clashes with the police and security forces in shantytowns. In 2005, after the protests that took place further to John Garang’s death5 and led to wide confrontations between South Sudanese and Northern Sudanese people, many police and security camps were established in shantytowns in order to repress any resumption of protests, as it happened in 2013.

In 2013, the young people from peripheral areas of Khartoum went out in protest against the new economic measures (mostly from Umbadda, Haj Yousif, Mayo). The response from the government was very violent, making Rapid Forces militia shoot and kill protesters. It was a very shocking and awful experience for people, especially for these youth who demonstrated and for the families of the victims from peripheral areas.

In contrast, the systematic use of violence by police and security forces in the December uprising against a middle-class population is unprecedented in their areas. The dreadful experience it represented for them became a strong reason to continue protesting.

But in fact neither those systematic use of violence is new for Khartoum peripheral population, nor that middle class people are the first to experience it.

Notes

- See interview with Magdi El Gizouli, same special issue. ↩︎

- Planned urban areas means first, second, or third class areas, which are a legal planning designation, determine the size, place, services, and materials of building in different parts of Khartoum. While old urban areas means the former villages which included in the urban boundaries without necessary re-planning the houses. The two forms of settlements are the middle/upper class residential areas. ↩︎

- See for example: Dahab et al.2019. ‘Deaths, injuries and detentions during civil demonstrations in Sudan : a secondary data analsis’. Conflict and Health. (2019) 13 :16. ↩︎

- According to the governmental law in Khartoum, selling and drinking of alcohol is prohibited, usually punished by lashes, fines and imprisonment. ↩︎

- Former leader of SPLA the main political party/army led the people of South Sudan. ↩︎