Introduction: Premature Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization refers to a sustained decline in either the share of manufacturing employment or its contribution to total value added in the economy. This phenomenon, especially when it occurs prematurely, has significant implications for women’s economic empowerment. Premature deindustrialization results in lower industrial employment and leads to peaks in industrial employment at lower levels of GDP per capita.1 This shift weakens long-term productivity and economic growth by reducing the role of manufacturing—a sector with high potential for innovation and value creation—while pushing the labor force into the services sector, where productivity gains are often more limited.

As economies move away from manufacturing before achieving substantial industrialization, women’s share of industrial jobs diminishes, contributing to the “defeminization” of labor. Capital-intensive industrial upgrading generally favors male employment, and premature deindustrialization exacerbates this gender bias. A direct relationship between deindustrialization and the defeminization of labor is especially evident in premature deindustrializers. Since women’s employment is more responsive to output fluctuations, a drop in manufacturing prices results in a greater decline in women’s share of manufacturing jobs compared to men’s, reducing their bargaining power and amplifying the male bias in industrial upgrading. These trends are particularly pronounced when manufacturing industries are less competitive and unable to withstand price declines.2

Several MENA countries have experienced premature deindustrialization, where the shift away from manufacturing occurred before reaching higher income levels or substantial industrialization. In Algeria, this was driven by heavy reliance on oil exports, which discouraged investment in manufacturing. Early deindustrialization in Egypt stemmed from structural adjustment and trade liberalization policies, which exposed the manufacturing sector to global competition. Morocco, while maintaining some high-value manufacturing sectors, has seen a decline in its overall manufacturing share due to a focus on integrating into global value chains rather than fostering deeper domestic industries.3

Premature deindustrialization in MENA is driven by a combination of global economic developments, resource dependency, policy failures, and geopolitical factors. Globally, the slowdown in manufacturing growth since the 1970s and the rise of capital-intensive production limited job creation in manufacturing sectors. Global value chains also concentrated profits in high-value activities like R&D and marketing, leaving manufacturing to suffer from low value capture and suppressed wages.4 In resource-rich countries like Saudi Arabia and Oman, the “resource curse” discouraged industrial diversification, as oil wealth led to currency overvaluation and hindered competitiveness in manufacturing.5

Domestically, policy failures exacerbated deindustrialization. Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) policies often resulted in investments in low-tech sectors with limited forward and backward linkages to the broader economy. Neoliberal reforms in the 1980s, promoting trade liberalization and privatization, left domestic industries unprepared for global competition. MENA’s trade policies fell into the fallacy of composition: multiple countries pursuing similar export-oriented growth models targeting the same markets led to collective underperformance. With comparable factor endowments, manufacturing structures, and industrial policies centered on unconditional corporate subsidies, these economies ended up competing against each other. This competition drove down export prices, compounding the region’s economic challenges.6

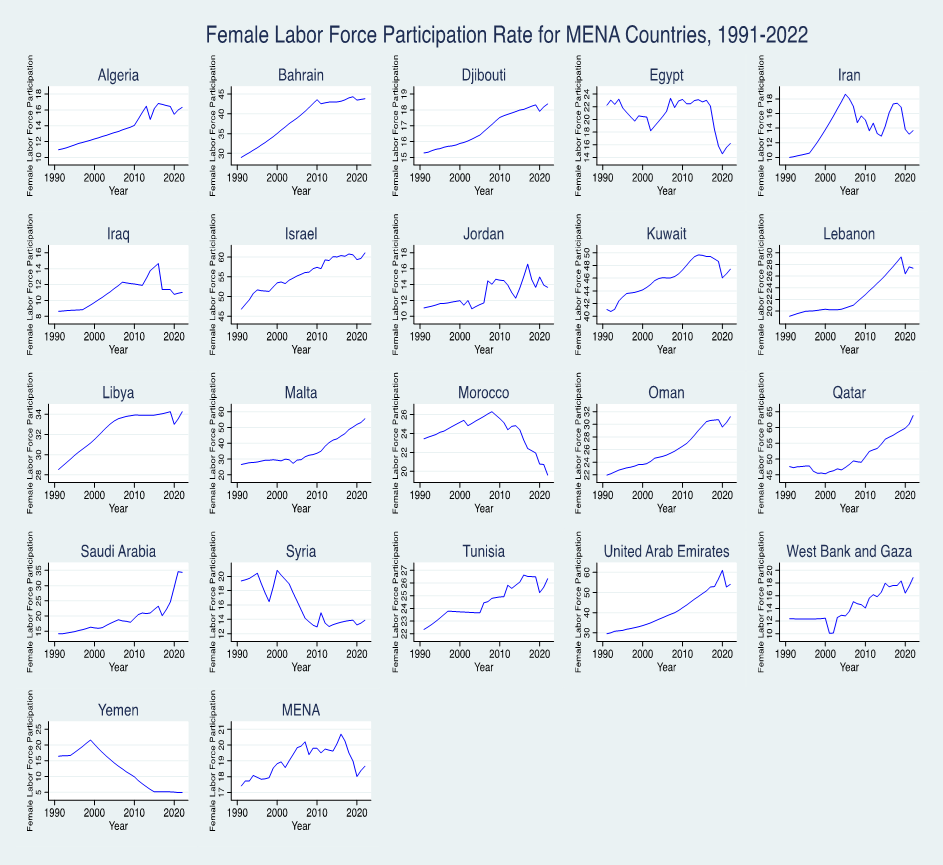

Geopolitically, countries like Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Palestine have endured significant challenges due to political instability and conflict. The Iran-Iraq War, the Gulf War, the Lebanese Civil War, the Syrian Civil War, and Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza have not only destroyed infrastructure but also exacerbated long-term deindustrialization and stagnation in the manufacturing sector. Figure 1 illustrates the employment share of industry in MENA from 1991 to 2022, showing significant variation across nations. Countries like Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Saudi Arabia, and Syria have experienced a continuous decline in industrial employment. In contrast, Egypt and Morocco exhibit a U-shaped pattern, with substantial deindustrialization occurring before the 2000s, followed by a recent rebound in industrial employment. Meanwhile, countries like Jordan, Qatar, Yemen, and the United Arab Emirates display an inverted U-shape. In summary, most MENA countries have undergone deindustrialization over the past three decades, although the timing of the sector’s contraction and its effects on employment varies across nations.

Figure 1: Share of industry in total employment in MENA, 1991-2022

Author’s calculations from World Development Indicators

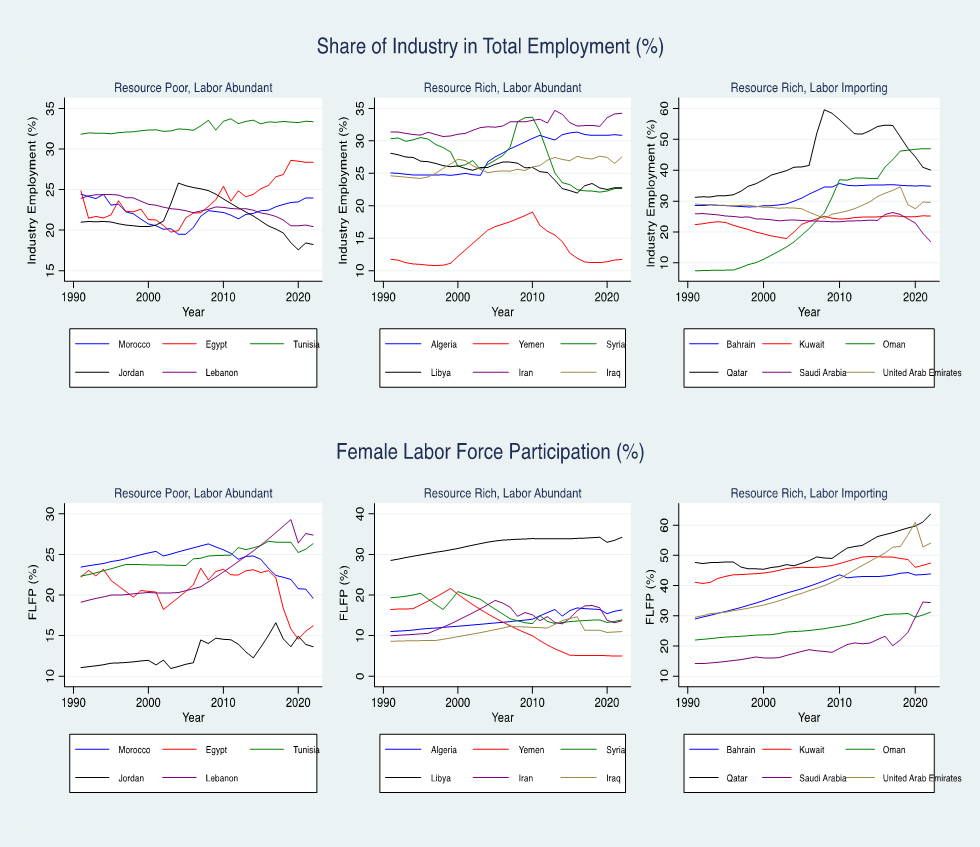

Weak feminization of the labor force under export-oriented industrialization

The relationship between industrialization and female labor force participation (FLFP) in MENA countries has been shaped by an interplay of development strategies, natural resource wealth, and deeply rooted gender norms. As many developing countries transitioned from import substitution to export orientation in the 1970s and 1980s, along with the adoption of structural adjustment policies, they witnessed a feminization of their labor forces. Export-oriented industrialization (EOI), particularly in labor-intensive industries like textiles and garments, tends to promote feminization.7 Several MENA countries followed these structural adjustment policies and saw a significant informalization of their labor markets. However, their experiences with the feminization of the labor force have been varied and generally limited (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Female labor force participation, 1991-2022

Author’s calculations from World Development Indicators

For example, Morocco initially experienced feminization driven by the growth of labor-intensive industries during their transitions to EOI, but subsequent deindustrialization and capital deepening have led to a decline in female employment in manufacturing sectors.8 Similar patterns are observed globally, where shifts from labor-intensive to capital-intensive production often reduce opportunities for women.9 In contrast, resource-rich Gulf countries have shown limited feminization of their national labor force, largely due to their reliance on oil revenues, the availability of affordable migrant labor, and cultural preferences for public sector employment among women. Figure 3 illustrates the weaker feminization of the labor force in resource-rich, labor-abundant MENA countries (Algeria, Yemen, Syria, Libya, Iran, Iraq). The labor-importing, resource-rich countries of MENA (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) exhibit different dynamics in female employment. While some of these countries have higher female labor force participation rates than the MENA average (Figure 3), expatriates dominate private and domestic sector female employment in these economies.10

Figure 3: Industry employment share and female labor force participation according to natural resource wealth, 1991-2022

Author’s calculation from World Development Indicators

Occupational gender segregation

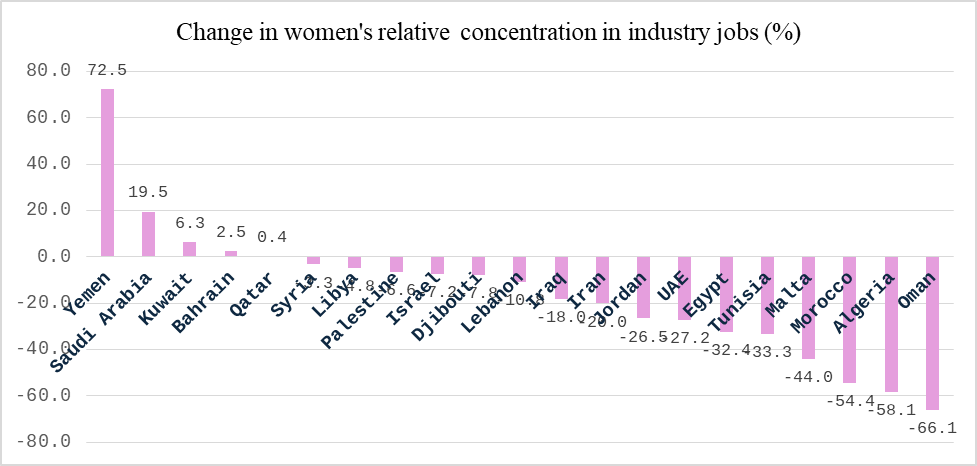

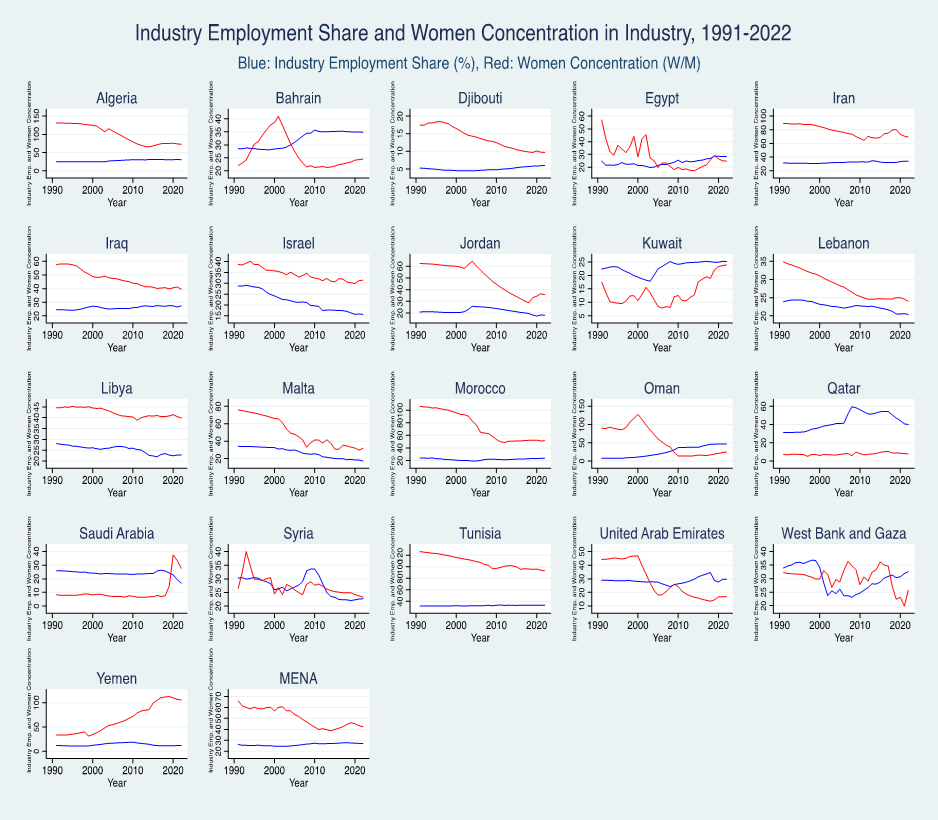

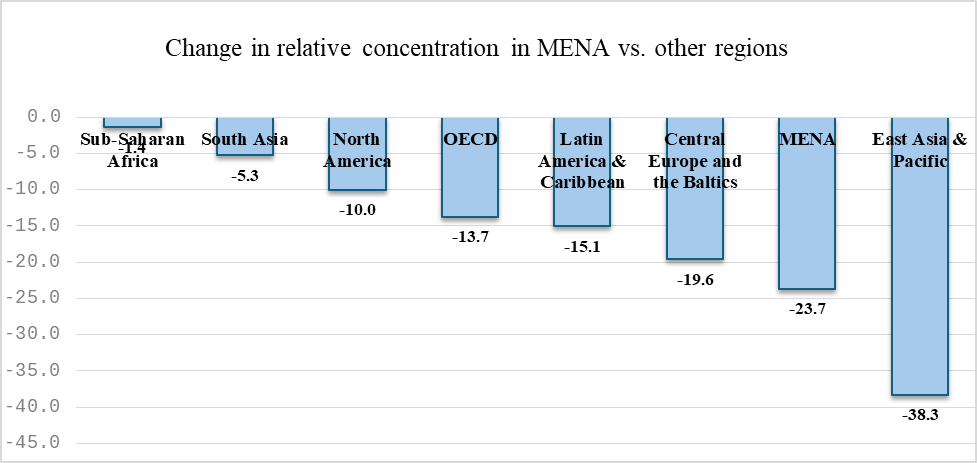

Across MENA, the persistence of occupational gender segregation further limits women’s ability to transition into male-dominated sectors, even if economies manage to diversify. Figure 4 and 5 illustrates that gender-based job segregation has increased in MENA countries from 1991 to 2022, highlighting a decline in women’s access to industrial employment. Gender job segregation is measured as the ratio of women’s share of industrial employment to men’s share, referred to as “women’s relative concentration in industrial employment”. While this trend is not unique to MENA, Figure 6 shows that the region experienced one of the sharpest declines in women’s relative concentration in industrial jobs (-23.7 percent), second only to East Asia and the Pacific (-38.3 percent), the world’s most industrially dynamic region. These patterns highlight that MENA’s performance remains concerning, even compared to other regions undergoing rapid industrial change.

Figure 4: Change in women’s relative concentration in industry jobs in MENA countries, 1991-2022

Author’s calculation from World Development Indicators

Figure 5: Industry employment share and women’s concentration in industry, 1991-2022

Author’s calculation from World Development Indicators

Figure 6: Women’s relative concentration in industry jobs in MENA in comparison to other regions, 1991-2022

Author’s calculation from World Development Indicators

However, there are four countries in MENA that deviate from this trend. Yemen and Saudi Arabia have seen the largest increases in women’s relative concentration in industry (Figure 4). The ongoing conflict in Yemen has paradoxically contributed to a rise in female representation in the industrial sector. As many men have been killed or displaced, the number of female-headed households has increased, pushing women to take on non-traditional roles in the labor market.11 In Saudi Arabia, women’s entry into traditionally male-dominated sectors like manufacturing and construction has been notable since the implementation of Vision 2030. Women have increasingly participated in textile production, food processing, and electronics manufacturing.12 The gendered employment impacts of deindustrialization in the region can be summarized based on Figures 2 and 5. In most MENA countries, declining industrial employment shares (deindustrialization) correlate with reduced women concentration in industry (Figure 5). Furthermore, female labor force participation stagnates or decreases, with limited absorption of women into other economic sectors in countries such as Egypt, Iran, Morocco, and Syria (Figure 2). On the other hand, countries like Israel, Bahrain, the UAE, Malta, and Yemen exhibit signs of deindustrialization but maintain or slightly improve female labor market outcomes despite industrial sector declines. Yemen stands out as an exception, showing an increase in female concentration in industry despite overall deindustrialization. In other cases, female labor force participation increases because declining industry shares are offset by diversification into other sectors. For instance, Malta has seen a rise in FLFP, driven by government policy interventions with a shift toward a service-based economy that has expanded opportunities in sectors like healthcare, education, and public administration.13

The need for policy reform

Deindustrialization trends across the MENA region, along with their gendered impacts, highlight the urgent need for targeted policy reform. The region’s struggles with premature deindustrialization, dependence on natural resources, and the uneven effects of trade liberalization have hindered industrial growth and deepened gender employment inequalities. Women’s declining presence in industrial jobs points to the effect that persistent barriers such as occupational segregation and limited opportunities in non-traditional roles continue to exert.

Addressing these challenges requires deliberate policies to diversify industrial activity, incentivize female employment in emerging sectors, and dismantle occupational segregation. Without such actions, the untapped economic potential of half the population will continue to undermine inclusive development goals and broader efforts to empower women economically.

Governments can promote gender inclusivity in industrial policy by adopting reciprocal control mechanisms, such as subsidies, tax breaks, or credit access contingent on firms meeting gender equity criteria.14 South Korea’s industrialization strategy, which tied state support to performance goals like export targets and technology upgrades, offers a model that could be adapted to include gender equity goals, such as mandating a minimum percentage of female representation in key industries. Public investments must prioritize social reproduction infrastructure, including publicly funded childcare, elder care, and healthcare, to reduce women’s unpaid labor burden and facilitate greater workforce participation. Central banks can adopt innovative tools, such as asset-based reserve requirements, to direct resources toward gender-equitable lending practices that support firms with equal representation of women.15 Incorporating gender criteria into trade agreements and leveraging development banks for inclusive investments can further expand women’s economic opportunities, ensuring their equitable participation in industrial and technological advancements.

This Policy Brief was produced with support from Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

- Rodrik, D. (2016). Premature deindustrialization. Journal of Economic Growth, 21(1), 1–33.

Timmer, M., de Vries, G. J., and de Vries, K. (2015). Patterns of structural change in developing countries. In J. Weiss & M. Tribe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Industry and Development (pp. 65–83). Routledge.

Tregenna, F. (2009). Characterizing deindustrialization: An analysis of changes in manufacturing employment and output internationally. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(3), 433–466 ↩︎ - Greenstein, J., and Anderson, B. (2017). Premature deindustrialization and the defeminization of labor. Journal of Economic Issues, 51(2), 446–457. ↩︎

- Ravindran, R., and Babu, M. S. (2023). Premature Deindustrialization and Income Inequality Dynamics: Evidence from Middle-Income Economies. The Journal of Development Studies, 59(12), 1885-1904.

Ravindran, R., and Babu, M. S. (2022). Premature deindustrialization and growth slowdowns in middle-income countries. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics,62(1), 377-389. ↩︎ - Powers, C. (2024). Deindustrialization in the Middle East and North Africa. Noria Research Middle East & North Africa. Available at: https://noria-research.com/mena/deindustrialization-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/. ↩︎

- Doğruel, F., and A. S. Doğruel. (2019). Chinese Economic Expansion, Openness, Resource Curse and Deindustrialization in the MENA Region. Ekonomi-tek 8, no. 2: 25–46.

Ravindran, R., and Babu, M. S. (2022). Premature deindustrialization and growth slowdowns in middle-income countries. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics,62(1), 377-389. ↩︎ - Powers, C. (2024). ↩︎

- Standing, G. (1999). Global feminization through flexible labor: A theme revisited. World Development, 27(3), 583–602.

Çağatay, N., Elson, D., and Grown, C. (1995). Introduction to the special issue on gender, adjustment, and macroeconomics. World Development, 23(11), 1826–1836. ↩︎ - Dildar, Y. (2021). Gendered patterns of industrialization in MENA. Middle East Development Journal, 1513(1), 128–149. ↩︎

- Tejani, S., and Milberg, W. (2016). Global defeminization? Industrial upgrading and manufacturing employment in developing countries. Feminist Economics, 22(2), 24–54. ↩︎

- Dildar, Y. (2021). ↩︎

- Patchett, H., and F. Al-Ammar. “The Repercussions of War on Women in the Yemeni Workforce.” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. Available at: https://devchampions.org/publications/policy-brief/The_Repercussions_of_War_on_Women_in_the_Yemeni_Workforce. ↩︎

- Al-Sheikh, H. (2023). “The Spectacular Surge of the Saudi Female Labor Force.” Brookings, Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-spectacular-surge-of-the-saudi-female-labor-force/. ↩︎

- Borg Caruana, J. (2023). “Quarterly Review 2023: Female Participation in the Labor Market.” Central Bank of Malta Quarterly Review, Central Bank of Malta, Available at: https://www.centralbankmalta.org/site/Reports-Articles/2023/Women-labour-market.pdf?revcount=3061#page=10.48. ↩︎

- Seguino, S. (2022). Industrial Policy and Gender Inclusivity. In A. Oqubay, C. Cramer, H.-J. Chang, & R. Kozul-Wright (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Industrial Policy (pp. 429-447). Oxford University Press. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎