The emergence of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) as key players in global financial markets is one of the most significant developments of the past few decades. Since 2005, the number of SWFs has grown from 50 to 176. At the time of writing, SWFs collectively manage assets surpassing $12 trillion — a figure greater than all global hedge funds and private equity firms combined.1 Among the 20 largest SWFs, eight originate from Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – specifically, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Together, these funds control over $4.9 trillion— a sum exceeding the GDP of Germany, the world’s fourth-largest economy.2 Historically, Gulf-based SWFs have been known for their conservative investment strategies. However, a paradigm shift has emerged with these funds adopting more aggressive approaches, channeling billions into large-scale infrastructure projects, seeding new industries, and acquiring stakes in some of the world’s most influential corporations.

The shift is particularly evident in Saudi Arabia. There, the Public Investment Fund (PIF) has assumed the central role in executing the kingdom’s ambitious post-oil diversification agenda, Vision 2030. Launched in 2016, Vision 2030 aims to stimulate private sector growth, increase the share of non-oil exports in GDP, and develop landmark infrastructure projects to reduce Saudi Arabia’s dependence on oil. At the heart of this strategy lies the transformation of the PIF from a relatively obscure development fund into the world’s largest SWF.3 Indeed, the Saudi government has set ambitious targets for the PIF, seeking $2 trillion in assets under management by 2030. If the objective is met, the PIF’s holdings will be $350 billion greater than those that are today managed by the world’s largest SWF, Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG).4

PIF assets have already seen exponential growth, increasing from $150 billion in 2015 to $925 billion in 2023.5 Domestically, the fund spearheads iconic infrastructure projects like the $500 billion futuristic city NEOM. It has also established over 60 companies across sectors, from coffee production to defense and military industries and renewable energy. Internationally, meanwhile, the PIF has become one of the most active SWFs, investing $53 billion between 2022 and 2023—19% of the total capital deployed by all SWFs during the period.6 Its investments span from high-profile stakes in companies like Amazon and London’s Heathrow Airport to football clubs, including the one which brought Cristiano Ronaldo to Saudi Arabia.7 Within the financial sector, the PIF has made significant inroads into private equity, notably contributing $45 billion to SoftBank’s $100 billion techno-focused venture capital Vision Fund, the largest single commitment or investment ever made by a SWF.

The conventional view portrays SWFs as rational, apolitical entities driven by financial returns.8 Yet, development-oriented SWFs like the PIF challenge this perception: Serving as dynamic instruments of state-led economic transformation, these institutions appear animated by both domestic politics and global economic strategies.

This study interrogates the driving forces behind the PIF’s dramatic revamp and expansion. In doing so, it delineates why the PIF’s evolution is best understood as a function of the interplay between a host of economic and political factors. Providing the macroeconomic backdrop for the PIF’s invigoration, we will contend, are the dual imperatives of economic diversification and industrial upgrading. Politically, meanwhile, the PIF’s expansion has been compelled by challenges presented to Saudi leaders in an era of demographic growth and structural adjustment. We will further argue that it is this same interplay between politics and economics which explains the PIF’s institutional design and use. Economically, the fund has facilitated the centralization of governance, granting the government greater control over policy planning and implementation. Politically, it has enabled policymakers to sidestep the veto players which previously obstructed reform. As a tool of this construction, the PIF has materialized the personalization of power in Saudi Arabia under de-facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman (MbS).

The study proceeds as follows: the first section situates the PIF within Saudi Arabia’s broader economic diversification efforts and the consolidation of political authority under MbS. The second section explores the PIF’s governance framework, highlighting its alignment with international best practices while emphasizing how the SWF streamlined centralized decision-making. Sections three and four establish the dual economic and political dimensions of the PIF’s domestic and international investment activities. Here, evidence will be marshalled to demonstrate how the PIF provides an instrument for policymakers to exert greater control over both domestic and international policy initiatives.9

The Dilemmas of a New Era

The rise of the PIF is intrinsically linked to the rise of Crown Prince MbS. At the beginning of 2015, there was a change of leadership in Saudi Arabia. After the death of King Abdullah—who had ruled the Kingdom for 10 years—his younger brother Salman ascended to the throne. Along with the throne itself, Salman inherited his half-brother, Prince Muqrin, as Crown Prince. To fill out the line of succession, Salman appointed Mohammed bin Nayef (MbN) as Deputy Crown Prince, the latter’s reputation as a key security figure informing the choice.10 In relatively short order, however, the King moved to reset the deck so as to consolidate his power. First, he orchestrated the dismissal of Prince Muqrin, after which MbN was promoted to Crown Prince and King Salman’s son MbS was raised to Deputy Crown Prince.11 Next, King Salman delegated substantial authority to MbS in day-to-day governance. With this leeway, MbS was eventually able to undermine MbN’s position. Manipulating staffing within the Ministry of Interior was a big part of this: one of the most notable moves was the removal and eventual exile of Sa‘ad al-Jabri, a key aide to MbN.12 Then, in June 2017, King Salman elevated MbS to the post of Crown Prince. To clear up any ambiguity on the swap, MbN was made to pledge allegiance to the new Crown Prince on a televised event.13

As part of this ascent to power, MbS took the lead in re-articulating Saudi Arabia’s economy. Early on, he was elevated as chairman of the Council of Political and Security Affairs and the Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA). These positions granting the prince de facto control over every critical economic portfolio in the Kingdom.

Control was used to serve a number of ends, prominently including the project of economic transformation. MbS first spelled out his intentions on this front during an interview with Al Arabiya in April 2016, when he introduced the aforementioned Vision 2030. Bernard Haykel interprets MbS’s calculations as follows: “Ultimately, MBS wants to base his legitimacy on the economic transformation of the country and its prosperity (and) sees his consolidation of power as a necessary condition for the changes he wants to make in Saudi Arabia”.14

Enter the PIF

Institutional mechanisms were needed to advance the transformation being aspired for. MbS identified a sovereign wealth fund as one perfectly suited for purpose and set about commandeering the PIF. Once a vault for excess oil revenue, the PIF was expressly rewired into an instrument for the Crown Prince’s economic project. Within a few years, this once neglected investment vehicle was made “not just an investment arm for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia”, in MbS’s words, “but an essential engine for economic diversification and job creation”.15

Saudi Arabia’s heavy dependence on oil revenues has long shaped its political and economic landscape, with oil rents constituting approximately 87% of the government’s annual budget, 42% of the nation’s GDP, and 90% of export earnings.16 The consequence of this reliance became starkly evident beginning in 2014. Over the next two years, oil prices dropped 70%, one of the most significant and prolonged declines in history.17 While briefly recovering thereafter, the Covid-19 pandemic provoked another sharp fall, with prices collapsing by 87% between January and April 2021.18

It was in response to the economic hardships precipitated by the 2014-2016 decline that the Saudi government introduced Vision 2030. In substance, the plan focuses on expanding the private sector, increasing job creation, and fostering economic growth in sectors beyond oil. In specifics, Vision 2030 seeks to increase the private sector’s contribution to GDP from 40% to 65%; to raise non-oil exports’ share of non-oil GDP from 16% to 50%; and to boost the GDP contribution of small and medium-sized enterprises from 20% to 35%.19 In the labor market, the plan targets a fall in unemployment from 11.6% to 7%. To power non-oil growth and substantiate the economy’s opening to the world, Vision 2030 also looks to grow foreign direct investment (FDI) from 3.8 to 5.7% GDP.20 And in the engine room of everything is the PIF: Vision 2030 charges the Fund with helping “unlock strategic sectors requiring intensive capital inputs”, which the strategy’s authors see as necessary for “developing entirely new economic sectors and establishing durable national corporations”.21

The Balancing Act: the PIF, Reforms and Regime Stability in Saudi Arabia

Economic diversification is undoubtedly a key impetus for PIF activities. That said, the SWF has missions extending further afield as well. Indeed, the PIF is one of the main instruments by which the current generation of Saudi leaders is attempting to buttress the stability of the regime.

Traditionally, Saudi rulers have used the country’s vast oil resources to this end, financing a vast welfare system meant to purchase political quiescence. The legacies of these efforts remain quite visible: Two-thirds of Saudi workers are employed by the government, household energy is heavily subsidized, and health care and education are free.22 However, by 2015, troubles in the oil markets pointed to the possible exhaustion of this model. The drop in oil prices resulted in massive contractions of the Kingdom’s revenues. Between 2013 and 2016, the state’s income halved. By 2020, revenues had only recovered to 72% of the pre-oil shock level. As this was happening, moreover, the country was also coming face to face with major demographic pressures. With over 60% of the population under the age of 30, the ability of the government to maintain extensive welfare provisions into the future became an open question.23 To appreciate why, consider that in 2015, salary and allowance expenditures for public employees alone surpassed total oil income.24

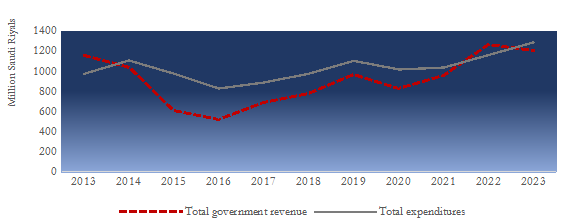

Result of all this, Saudi Arabia ran regular (and significant) budget deficits over the last decade (see Figure 1). To fund these deficits, the Kingdom sold huge sums of debt instruments on domestic and international markets. In 2023, in fact, Saudi Arabia overtook China as the largest issuer of international debt among emerging markets.25 In the aggregate, public debt skyrocketed by over 2 270% between 2014 and 2023—from an (extremely low) base of $11.8 billion $280 billion.26

Figure 1: Saudi Fiscal Trends (2013-2023)

Source: SAMA annual reports

Vision 2030 was designed to address the economic and political challenges presented by the Kingdom’s shifting fiscal horizon. In promoting new industries like entertainment and tourism, the team around MbS hoped to service a consumerist culture and create jobs for new labor market entrants. All in all, the focus was on building the conditions for sustainable economic growth. Even social liberalization policies, such as expanding cultural opportunities and allowing women to drive and join the workforce, retained an economic objective.

A fragmented state apparatus had historically impeded the Saudi government’s ability to coordinate and implement structural reforms.27 For decades, the Saudi state was defined by a system of segmented and hierarchical ministries and state agencies controlled by one senior prince or another28. Allowing for patrimonialism to flourish and clientelist networks to calcify, the Saudi state modality vested key actors with parochial interests, status quo biases, and what amounted to veto power over reform. Though presenting some political utility—the fragmented Saudi state functioned as a power-sharing mechanism and helped prevent elite splits—these arrangements encouraged policy stasis. It was due to them that various reform initiatives in the 1990s and early 2000s—including labor market “Saudization” and foreign investment reforms—came to naught, undermined by interagency feuds and competing interests.29

By positioning the PIF as the critical driver for Vision 2030’s cross-cutting transformative agenda, the team around MbS hoped to avoid the pitfalls which had compromised past reform pushes. Such hopes were grounded in reason. Positioned outside traditional state apparatuses and set up as independent investment and asset management companies, SWFs can greatly enhance the policy autonomy of political leaders. The appointment of loyalists to senior positions within a relevant fund can boost autonomy further, enabling rulers to design and execute policies with minimal interference. In the context of fragmented bureaucratic structures, such institutional design positions development-oriented SWF as a strategic tool to sidestep competing stakeholders, circumvent bureaucratic resistance, and press forward with a policy agenda.

PIF Governance and Power Consolidation

On March 23, 2015, the Council of Ministers passed Resolution No. 270. The decision transferred oversight of the PIF from the secretive and insulated Ministry of Finance to the Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA), a body chaired by MbS. The switch institutionalized the PIF’s operational and financial independence. Importantly, under CEDA’s oversight, the PIF was able to establish its own staff and board of directors.30

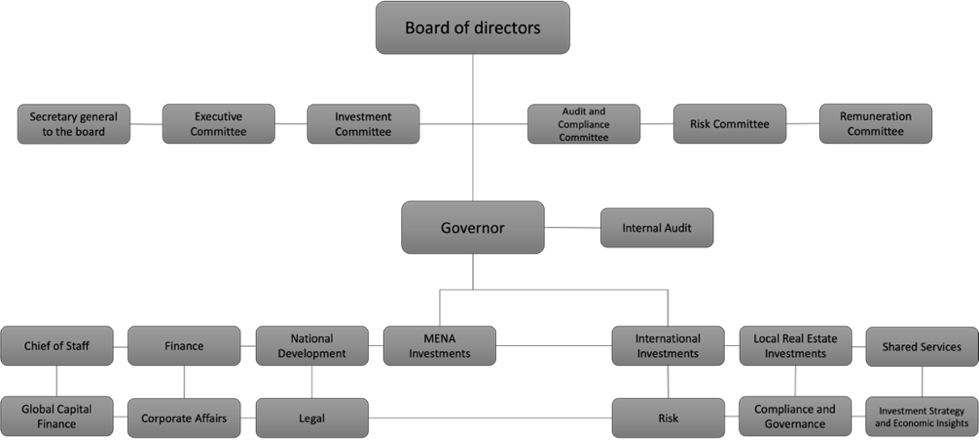

On paper at least, the governance regime for the PIF aligns closely with the IFSWF Santiago Principles. The board of directors is responsible for overseeing asset allocation and investment strategies. It is supported by an internal audit unit that ensures compliance with internal regulations. The governor acts as a key intermediary between the board and the executive management team. The latter is composed of technocrats and tasked with executing the fund’s objectives (Figure 2).

The Santiago Principles and SWF Governance

The Santiago Principles, developed by the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) in 2008, set global standards for SWF governance. At their core, the Principles concern transparency and accountability. The primary consideration underpinning their development was the idea of arm’s length governance: to wit, that governments should refrain from getting involved in SWF business and investment decisions. For instance, GAPP 9 of the Santiago Principles posits that “the operational management of the SWF should implement the SWF’s strategies in an independent manner and in accordance with clearly defined responsibilities”.31

Universally, it is the prerogative of governments to set an SWF’s general objectives and goals. Likewise, it is boards of directors which are responsible for devising the game plans for realizing those objectives. As such, board composition and the procedures determining composition are crucial to SWF governance. This is because in the final instance, an SWF’s sponsor (the principal) must delegate decision-making authority to the fund manager (the agent). Delegation opens the door to an adverse selection problem32, as the interests of the agents selected can diverge from those of principals. In this sense, governance structures and the appointment of agents to a fund’s governing body can become breeding grounds for considerable political interference and the (re)production of political alliances.

Figure 2. The PIF organizational structure

Source: PIF annual report 2021 (p.83)

Alas, the devil is in the details. Under the terms of the PIF law, MbS—as prime minister, chairman of CEDA, and chairman of the PIF—controls all the levers of PIF governance. He is also the sole authority responsible for board appointments.33

A consequence of this command structure is that the PIF’s board of directors corresponds closely to the network of loyalists which has ascended via MbS’s rise to power. All current appointees—most notably finance minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan and PIF governor Yasir Rumayyan—are trusted allies of MbS who owe their political (and commercial) fortunes to King Salman and the Crown Prince.34 This reality broaches basic questions about PIF governance. In Saudi Arabia as anywhere else, after all, loyalist appointees, even if personally competent, are likely to share in and support their principal’s policy agenda and to place the principal in the driver’s seat when it comes policy adoption and implementation.

At a basic level, the power structure MbS instantiated through the institution of the PIF has facilitated a staggering concentration of authority and resources. This not only enables the eschewing of preexisting institutional conventions—perceived to undermine autonomy in policymaking. It has also allowed for financing to be mobilized and allocated with speed and scale. The latter, as we will see, has resulted in a swift reordering of capital ownership in the Saudi economy.

PIF Investments

Domestic Activities: Diversification Meets Centralization

PIF activities in Saudi Arabia are grouped into two main portfolios: the Saudi Sector Development and Saudi Equity Holdings investment pools. The Saudi Sector Development portfolio (SSD) is focused on establishing and promoting the creation of high-priority sectors in the Saudi economy.35 The SSD represents 21% of the fund’s total assets under management, allocating capital across the thirteen strategic sectors that have been targeted by the government. To date, through the SSD, the PIF has capitalized more than 60 companies.

Whereas the SSD manages an extensive network of fully-owned subsidiaries, the PIF’s Saudi Equity Holdings (SEH) is charged with acting as a strategic, domestically-oriented investor. Within the SEH portfolio, the PIF holds equity stakes in both publicly listed and privately owned firms. In total, these stakes represent 32% of the PIF’s assets under management. Major investments include a 16% share in the oil giant Aramco and a 67% position in Ma’aden, which ranks among the world’s ten largest mining companies. The SEH also houses the PIF’s holdings in the financial sector, where it is the leading shareholder in the country’s largest banks (the Saudi National Bank, the Riyad Bank, and Alinma Bank).

Table 1. PIF Subsidiaries

| AMAALA | Real Estate Refinancing Company |

| KAFD Development and Management Company | The Helicopter Company |

| NEOM | The National Energy Services Company (TARSHID) |

| Qiddiya | Noon |

| Red Sea Global | Rua Al Madinah Holding |

| ROSHN | The Saudi Jordanian Investment Fund |

| Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI) | The Funds of Funds (Jada) |

| Saudi Coffee Company | Boutique Group |

| Saudi Cruise | Al Soudah Company |

| Saudi Entertainment Venture (SEVEN) | Jeddah Central Development Company |

| Saudi Information Technology Company (SITE) | National Security Services Company (SAFE) |

| Saudi Investment Recycling Company (SIRC) | Gulf International Bank – Saudi |

| Tahakom Investments Company | Saudi Information Technology Company |

| Water and Electricity Holding Company (Badeel) | Tatweer Education Holding Company |

| Elm Company | National Water Company |

| National Unified Procurement Company | Rua Al Madinah Holding Company |

| Saudi Agriculture & Livestock Investment Company | Sanabil Investments |

| Saudi Railway Company | Saudi Technology Development and Investment Company (TAQINA) |

| Diriyah Gate Company | Riyadh Air |

| Savvy Games Group | Al Ula Development Company |

Source: Data compiled from PIF annual reports and website

Beyond its contributions to enhancing industrial capabilities, localizing technologies, and creating employment opportunities, the PIF’s breadth of reach has concurrently improved oversight over economic development more generally. The latter is most evident when it comes to large-scale infrastructure projects like NEOM36 and Qiddiya37. Previous such initiatives, like the $100 billion King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) cluster first announced in 200538, faltered on the back of interagency squabbling and elite conflict.39 In the case of NEOM and Qiddiya, contrarily, the PIF has effectively bypassed such obstructions by serving as primary project financier and developer. To streamline things further, the SWF also established several subsidiaries directly responsible for piloting projects, government procurement, and launching joint ventures with foreign investors.

The verticality of the PIF’s authority and spread of its ownership has directly impacted the opportunities available to the Saudi private sector. For capital’s long reliant on government contracts and subsidies40, the PIF’s ubiquity has closed down, degraded, or significantly altered spaces for rent-seeking. This is especially evident when it comes to megaprojects. For politically-connected business elites41, these projects had long represented a primary site for accumulation, especially for those in the businesses of contracting and building materials.42 Upon the rise of MbS, however, the opportunity structure shifted. Saliently, the PIF acquired significant minority stakes in four leading construction firms for $1.3 billion in order to spearhead the development of megaprojects: El Seif Engineering Contracting Company, Nesma & Partners Contracting Company, Al Bawani Holding Company, and Al Mabani General Contractors Company.43 On the one hand, this directly entwined the firms in question with the state. In so doing, however, the PIF’s equity acquisitions (and subsequent apportioning of contracting opportunities) also reordered the hierarchy of private capitals in Saudi Arabia: In conjunction with 2017’s crackdown at the Ritz, the PIF’s investments elevated the el-Seif, al-Shawaf, Adham, and al-Turki families to the catbird seat while relegating traditional powers like the Bin Ladens to a subordinate position.

The Who’s Who of Contracting

The El Seif family, with deep royal ties, controls one of Saudi Arabia’s most influential construction conglomerates. Khaled El Seif, the company’s chairman, is married to Azza Al Sudairi, from the influential Sudairi family, closely associated with King Salman44. Similarly, Al Mabani was founded by Kamal Adham, a royal counsellor to Kings Faisal (1964-1975) and Khalid (1982-2005) and brother-in-law to King Faisal. Al Bawani, founded by Abdel Moeen Al Shawaf, also has close ties to the House of Saud45, while Nesma & Partners was established by the Al Turki family, with Saleh Al Turki, its chairman, holding prominent positions in Saudi business and diplomacy.46

In addition to PIF funding, Al Bawani has recently secured the contracts for major projects, including KAFD Towers phase two, the Red Sea Coastal Village, and Aramco’s Innovation Centre. Al Mabani has secured $1.7 billion in PIF contracts, including Six Flags Qiddiya, Riyadh Metro, and King Abdulaziz International Airport. Nesma & Partners was awarded contracts for metro stations, tunnels, and infrastructure in NEOM, Mecca, and Diriyah.47 El Seif is behind key projects such as the King Abduallah Financial District.

The fate of these families strikes a marked contrast with those of the bin Ladens and others enriched during the post-1970s build out of the Kingdom’s infrastructure.48 Bakr, Saad, and Saleh bin Laden were amongst those detained at Riyadh’s Ritz Carlton in November 2017.49 Like the hundreds of other businesspeople taken in, they faced unspecified corruption charges, with their release contingent on the transfer of their assets to the government.50 In the final instance, they were released after the Saudi government took control of 36.2% of the Bin Laden Group.51

The PIF’s rise has also shifted the game for those who once earned rents by acting as middlemen between foreign companies and the government. These days, those intermediaries are either being cut out of procurement deals altogether—with deals sealed directly between the foreign party and the PIF—or pushed into less profitable subcontractor roles.

This change is most visible in strategic sectors like defense and security. Recall that Saudi Arabia has historically been among the world’s largest military spenders by share of GDP.52 In the past, military procurement provided an especially lucrative opportunity for intermediaries (princes, not infrequently) who acted as local agents for international defense manufacturers.53 Alas, the PIF’s emergence onto the scene, in tightening the government’s control over the defense economy, has greatly reduced the take available. Key in this regard was the launch of the PIF’s Saudi Military Industries Company (SAMI) in 2017. SAMI seeks to localize 50% of the Kingdom’s military spending by developing technologies and manufacturing products in aeronautics, land systems, defense electronics, weapons and missiles, and emerging technologies.54 To advance its objectives, SAMI signed multiple agreements with defense contractors, including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and launched the SAMI L3 Harris Technologies, a joint venture with L3 Harris Technologies, one of the world’s largest aerospace and defense systems manufacturers.55 With the regime’s backing, SAMI has grown rapidly, expanding from just 360 employees to more than 3,600 people.56

In many ways, SAMI exemplifies how the PIF and its subsidiaries serve the dual purpose of (1) centralizing control and imposing more rigorous oversight over economic development (2) fostering technology transfer, building domestic industrial capacity, creating employment opportunities to absorb the national labor force, and ultimately diversifying the Kingdom’s economy. At the same time, it is notable that the firm’s achievements have shrunk spaces where private actors once intervened to turn a buck.

A Shift in Saudi Arabia’s International Investment Strategy

In addition to its sizable domestic investments, the Saudi government also tasked the PIF with leading its international investment strategy.57 Today, international assets are channeled into one of two portfolios: the International Diversified Pool (IDP) and International Strategic Investment Pool (ISI). The ISI pool is designed to establish strategic partnerships with innovative companies, attract foreign investments, and localize technologies in line with Vision 2030’s diversification efforts. The IDP pool, contrarily, seeks to position the PIF as a long-term institutional investor through a well-balanced, risk-weighted portfolio. In line with the goals of seeding new ecosystems, localizing technologies, and bolstering local private sector activity, 80% of PIF international investments are in industrials (20%), communication services (20%), consumer discretionary (20%), and financials (20%).

With the PIF in the lead, the Kingdom’s international investment strategy has become much more aggressive. Between 2014 and 2022, holdings of high-risk assets—FDI, equities, loans, and trade credit—grew by 239%, jumping from $164 billion to $556 billion.58 Leaders of resource-rich autocracies facing major threats often choose short-term, high-risk foreign investments to secure quick returns and stabilize their regimes.59 SWFs that adopt such risk strategies, rather than saving for the future, signal a focus on meeting immediate demands to stay in power. The move from a conservative approach to a more aggressive, risk-prone asset allocation strategy affords Saudi leaders quick access to liquidity in times of fiscal stress, enabling the government to address immediate budgetary needs. The PIF’s vertical structure and the personal influence MbS exerts over policymaking allowed the pivot. Some examples testify to the causal weight of these variables. PIF Governor Yasir Rumayyan has publicly recounted an instance where the entire PIF board voted against a risky investment proposal favored by MbS only to be shot down.60 The decision to invest $45 billion in Softbank’s Vision Fund was also taken solely by the Crown Prince following a meeting of less than an hour with SoftBank Group’s chairman Masayoshi Son, due diligence and risk analysis be damned.61 MbS also pushed through the injection of $2 billion into Jared Kushner’s new private equity firm months after the Trump Administration left office despite the investment being unanimously opposed by the PIF board’s investment committee.62

SAMA and the PIF

From the 1970s onward, the Saudi central bank, the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), was the guardian of the Kingdom’s sovereign wealth through its portfolio of foreign holdings. Since its creation, SAMA enjoyed substantial autonomy from the ruling family and had broad discretion in its operations.63 Recognized as a passive global investor, SAMA adhered to an investment strategy focused on low-risk and liquid assets, with a portfolio primarily comprised of US Treasury bills.64 The strategy hinged on the conventional wisdom that (1) natural resource revenues are finite and (2) commodity prices are prone to significant volatility, which can engender swings in government revenue and expenditure. Guided by these propositions, SAMA endeavored to promote fiscal stabilization by recycling extra income over financial markets through low-risk, conservative approaches. From 2003 to 2015, SAMA’s assets largely tracked oil prices, illustrating its role as a vault for oil surpluses (see Figure 4). Since the emergence of the PIF, however, SAMA’s assets have been on the decline: Even with oil revenues reaching a near-record $326 billion in 2022, SAMA’s assets under management were just $482 billion in 2023. For context, in 2014, SAMA’s portfolio was valued at $732 billion. The decline derived from the transfer of assets (and the transfer of dividends issued by Aramco) from SAMA to the PIF. In 2020, $80 billion from SAMA’s foreign reserves were moved to support PIF investment activities.65 (16% of the state’s shares in Aramco have also been transferred to the PIF).

Figure 4. Saudi sovereign wealth and oil price (2003-2023)

Source: data compiled from SAMA annual reports, Global SWF reports and US Energy Information Agency

Conclusion

Over the past decade, the PIF has transformed from an unknown development fund into one of the world’s most prominent SWFs. Its evolution illustrates the interplay between economic objectives and political imperatives, with diversification challenges intricately tied to the consolidation of power.

Economically, the PIF’s activities signal a shift in Saudi Arabia’s approach to managing its oil wealth. Rather than adhering to the conservative strategies of the past, the PIF has embraced a proactive investment model. These efforts align with Vision 2030’s goals of reducing dependency on oil revenues and creating a more dynamic and diverse economy. Politically, the PIF represents a vehicle for centralizing power and circumventing institutional bottlenecks which impede the reforms that rulers deem necessary for regime stability. The PIF’s rise reflects broader trends of authoritarian personalism under MbS, where economic transformation is wielded as both a tool for modernization and a means of legitimizing a claim to power.

The risks inherent to MbS’s use of the PIF should not be understated. The personalization of sovereign wealth management in Saudi Arabia may facilitate questionable choices that eat away at national wealth: Time will tell if large-scale infrastructure projects like NEOM and sizable high-tech investments such as the $45 billion capital injection into the techno-focused Vision Fund produce appropriate returns on investment. For now, though, caution should be the word (in the case of the Vision Fund, disaster might be more appropriate66). Especially in the Middle East, after all, large-scale infrastructure projects have yielded more white elephants than success stories.67

Beyond Saudi Arabia, the establishment of development-oriented SWFs have surged, with more than 30 such funds created since 2000 in countries ranging from Ireland, Turkey, and India to Gabon.68 Like the PIF, such SWFs are established to promote domestic economic development and lead industrial policy, often through the buildout of national infrastructure programs. In times of global decarbonization efforts and climate adaptation, though, the question begs asking: are these institutions up to the task?

Yes, development-oriented SWFs offer a potential avenue for reconfiguring patterns of economic development and addressing the challenges of policy implementation. By streamlining cumbersome decision-making processes often blamed for obstructing developmental goals, these funds could serve as effective tools for governments. But their effectiveness is far from assured. While using SWFs as pilot agencies can accelerate policy design and execution, the centralization of power this entails raises significant concerns about transparency and accountability. Without robust checks and balances, centralization risks fostering a weakening of governance mechanisms, policy capture and favoritism. As a result, while development-oriented SWFs may help overcome barriers to economic transformation, the methods by which they operate deserve scrutiny—particularly in an era of democratic backsliding.

1Alami, I., & Dixon, A. D. (2020). State capitalism(s) redux? Theories, tensions, controversies. Competition & Change, 24(1), 70–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529419881949

2Global SWF. (2024). 2024 Annual Report: SOIs Powering Through Crises. Global SWF. https://globalswf.com/reports/2024annual#preface-0

3 Established in 1971 as an investment arm of the Ministry of Finance, the PIF’s activities were initially confined to providing soft loans to nascent state-owned enterprises. However, following a major restructuring in 2015, the PIF evolved into a full-fledged SWF.

4 As of the GPFG’s $1 635 billion of assets under management by the end of 2023 (Global SWF, 2024).

5 Global SWF. (2024).

6 Ibid

7 Noble, J., Smith, R., England, A. (2022, October 10). Saudi Arabia Wealth Fund Commits $2.3bn to Football Sponsorships, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/ce556bac-30cc-49c6-b883-5cab67ce5379.

8 Abdullah Al-Hassan et al., (2013). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Aspects of Governance Structures and Investment Management, IMF Working Papers, 13/231: 34; Alsweilem, K. A., Cummine, A., Rietveld, M., & Tweedie, K. (2015). Sovereign investor models: (p. 138). Harvard Kennedy School.

9 Empirics are primarily drawn from the S&P Capital IQ and US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) databases. In addition, the analysis draws from the range of official PIF and government documentation from 2015 to 2024, as well as annual reports and financial statements.

10 Davidson, C. (2021). From Sheikhs to Sultanism: Statecraft and Authority in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Hurst & Company.

11 Hubbard, B. (2020). MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman (1st edition). Tim Duggan Books.

12 Leber, A. (2024). Personalization and domestic policy outcomes: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Democratization, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2024.2428269

13 Hope, B., & Scheck, J. (2020). Blood and Oil: Mohammed bin Salman’s Ruthless Quest for Global Power. Hachette Books.

14 Haykel, B. (2018, January 22). The Rise of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Reveals a Harsh Truth, The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2018/01/22/the-rise-of-saudi-arabias-crown-prince-reveals-a-harsh-truth/.

15 PIF. (2023b). Santiago Principles Self-Assessment Report. Public Investment Fund: 3

16 Nurunnabi, M. (2017). Transformation from an Oil-based Economy to a Knowledge-based Economy in Saudi Arabia: The Direction of Saudi Vision 2030. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 8(2), 536–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-017-0479-8

17 World Bank. (2018). Global Economic Prospects, January 2018: Broad-Based Upturn, but for How Long? Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1163-0

18 EIA. (2023). Europe Brent Spot Price FOB. U.S Energy Information Administration. https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/rbrteM.htm

19 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. (2016). Vision 2030 (p. 85). Council of Economic and Development Affairs.

20 Ibid

21 Ibid

22 Hertog, S. (2018). Challenges to the Saudi Distributional State in the Age of Austerity. In M. Al-Rasheed (Ed.), Salman’s Legacy: The Legacy of a New Era in Saudi Arabia (pp. 73–96). Oxford University Press.

23 Saudi Press Agency. (2021, February 10). SAMI’s First Saudi-U.S. Partnership Begins Operations. Saudi Press Agency. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2188303

24 Hertog, S. (2018)

25 Gokoluk, S. (2024, June 19). Saudi Arabia Dethrones China as Top Emerging-Market Borrower. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-06-19/saudi-arabia-dethrones-china-as-top-emerging-market-borrower

26 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. (2024). Reports & Statistics. National Debt Management Center. https://ndmc.gov.sa/en/stats/Pages/default.aspx

27 Hertog, S. (2010a). Princes, Brokers, and Bureaucrats: Oil and the State in Saudi Arabia. Cornell University Press.

28 Al-Rasheed, M. (2005). Circles of Power: Royals and Society in Saudi Arabia. In P. Aarts & G. Nonneman (Eds.), Saudi Arabia in the Balance: Political Economy, Society, Foreign Affairs (pp. 185–2013). Hurst & Company.

29 Hertog, S. (2010a)

30 PIF. (2017). The Public Investment Fund Program (2018-2020). Public Investment Fund: 92

31 IFSWF. (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds Generally Accepted Principles and Practices: “Santiago Principles”. International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds: 8.

32 Miller, G. J. (2005). The Political Evolution of Principal-Agent Models. Annual Review of Political Science, 8(1), 203–225. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.8.082103.104840

33 Public Investment Fund Law, 13 (2018). https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/GDP%20Attachments/PIFLawDocument-En.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0ZZ6G2SMQksyLjzpo1CN0O2dAR81QiHTepJxbr_tWlZbLaKLNznaSrIxk

34 Montambault Trudelle, A. (2023). The Public Investment Fund and Salman’s state: The political drivers of sovereign wealth management in Saudi Arabia. Review of International Political Economy, 30(2), 747–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2069143

35 The Saudi government stipulates that PIF investments “accelerate diversification and dynamism in the economy and unlock latent potential” but also “new future-focused employment opportunities for Saudi nationals and residents”. See: PIF. (2022). PIF Annual Report 2022 (p. 69). https://www.pif.gov.sa/Annual%20Report%20EN/PIF%20Annual%20Report%202022.pdf

36 NEOM is a futuristic multi-purpose metropolis to become a global hub for industry, research, and development

37 Qiddiya set to become a global entertainment capital boasting arts centers, festival grounds, an F1 racing circuit, and theme parks.

38 The KAEC was to be given a free zone status with a separate legal status, including distinct regulatory, licensing, and fee frameworks. In the end, however, this never came to pass, as the resistance of established government entangled the KAEC in paralyzing infighting. See: Hertog 2010a.

39 KAEC. (2022). KAEC. KAEC. https://www.kaec.net/

40 Kamrava, M., Nonneman, G., Nosova, A., & Valeri, M. (2016). Ruling Families and Business Elites in the Gulf Monarchies: Ever Closer? Chatham House Research Paper, 14.

41 There is an inherent opacity to the specifics of contracts underpinning the private sector’s operations in construction developments. Consequently, there is no reliable way of precisely quantifying the effect of PIF large-scale projects for the private sector. This is not, however, to deny that PIF megaprojects are very lucrative opportunities for business elites. $1.43 billion worth of contracts were granted in 2021 for various construction and transport projects connected to NEOM. Moreover, the PIF-owned Red Sea and Qiddiya had accorded more than $4 billion in contracts, primarily to Saudi companies. Furthermore, in 2022, the SWF committed $20.4 billion for its Jeddah Central project, $2.9 billion to build 2 700 hotel rooms and attractions in Abha, and the PIF-owned Roshn attributed $933 million worth of contracts for real estate projects.

See: Construction Daily. (2021, September 2). NEOM tenders re-energise Saudi building sector, says report. Construction Daily. https://constructiondaily.news/neom-tenders-re-energise-saudi-building-sector-says-report/; Arab News. (2020, November 26). Qiddiya awards $533m contracts for giga-project to Saudi firms. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1768746/business-economy; Arab News. (2021, February 8). Roshn boosts Vision 2030 with $933m contract spree. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1805746/business-economy; Global SWF. (2024). 2024 Annual Report: SOIs Powering Through Crises. Global SWF. https://globalswf.com/reports/2024annual#preface-0; The Economist. (2021, November 13). No Tourist Mecca. The Economist, 49–50; Rahman, F. (2021, June 15). Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea project awarded contracts woth 14.5bn riyals last year. The National News. https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/travel-and-tourism/saudi-arabia-s-red-sea-project-awarded-contracts-worth-14-5bn-riyals-last-year-1.1241964

42 Hanieh, A. (2018). Money, Markets, and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108614443

43 PIF. (2023a). PIF announces investments in four leading companies in Saudi Arabia’s construction services sector. PIF. https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/Pages/NewsDetails.aspx?NewsId-239/PIF-Announces-Investments-in-Four-Leading-Companies-in-Saudi-Arabias-Construction-Services-sector

44 Khaled El Seif is married to Azza Al Sudairi; she hails from the same influential family as King Salman’s mother, Hussa bint Ahmed Al Sudairi, as well as King Salman’s late spouse Sultana bint Turki Al Sudairi.

See: Burack, E. (2023, June 1). Who Is Rajwa Al Saif? Meet Crown Prince Hussein of Jordan’s Wife. Town&Country. https://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/tradition/a43324753/who-is-rajwa-al-saif/

45 Abdel Moeen Al Shawaf was granted permission by the government to open one of the first Saudi publishing houses, and his wife used to run a charity with King Abdullah’s wife.

46 Steinke, L. (2023, August 29). The winners and losers and MbS’s plan for Saudi to join the global economic premier league. Diligencia. https://www.diligenciagroup.com/blogs/the-winners-and-losers-of-mbss-plan-for-saudi-to-join-the-global-economic-premier-league

Saleh Al Turki was appointed Honorary Consul of the Republic of Austria, chairman of the Council of Saudi Chambers and mayor of Jeddah in 2018.

47 Farhadi, F. (2024, January 25). 7 Top Construction Company in Saudi Arabia in 2024. Construction Magazine. https://neuroject.com/construction-company-in-saudi-arabia/

48 Senior Bin Laden family members, including Bakr, Saleh, and Saad, directly negotiated with Abdullah, with a special unit within the royal government dedicated to their business interests.

49 Hope & Scheck, 2020

50 Davidson, C. (2021)

51 Rashad, M., & El Yaakoubi, A. (2021, May 13). Saudi releases Bin Laden construction tycoon detained in 2017 corruption sweep. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/saudi-releases-bin-laden-construction-tycoon-detained-2017-corruption-sweep-2021-05-13/

52 Tian, N., Kuimova, A., Lopes Da Silva, D., Wezeman, P. D., & Wezeman, S. T. (2020). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019. [SIPRI Fact Sheet]. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute: 12

53 Most famously, BAE Systems, a UK manufacturer of defense equipment, was embroiled in paying bribes to senior members of the Saudi royal family to secure massive military equipment contracts. In 2007, a Serious Fraud Office (SFO) investigation revealed that £120 million a year was sent by BAE Systems from the UK to two Saudi embassy accounts in Washington. The accounts were a channel to Prince Bandar bin Sultan Al Saud, Saudi ambassador to the US from 1983 to 2005, who acted as the middleman between the Saudi government and BAE Systems (BBC, 2007).

54 SAMI. (2021). Business Divisions. Saudi Military Industries Company. https://www.sami.com.sa/en

55 Saudi Press Agency. (2021, February 10). SAMI’s First Saudi-U.S. Partnership Begins Operations. Saudi Press Agency. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2188303

56 Vidal, A. (2022, November 20). Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI): Fueling the Growth of Saudi Defense Industry. Gulf International Forum. https://gulfif.org/saudi-arabian-military-industries-sami-fueling-the-growth-of-saudi-defense-industry/#:~:text=As%20of%20November%202022%2C%2012,and%20possibly%20South%20Korea’s%20Hanwha.

57 Per the PIF’s public communications, the fund is tasked to “invest in international sectors, in line with Vision 2030 objectives, which include growing and diversifying PIF’s assets and returns, establishing economic and strategic partnerships, and expanding the Kingdom’s reach and influence as a leading powerhouse in the global economy” (PIF, 2021, p. 31).

58 Daoud, Z. (2023, July 18). How MBS’s Saudi Wealth Fund Could Take US Yields Higher. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-19/how-mbs-s-saudi-wealth-fund-could-take-us-yields-higher-chart

59 Kendall-Taylor, A. (2011). Instability and Oil: How Political Time Horizons Affect Oil Revenue Management, Studies in Comparative International Development 46, no. 3: 321–48, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-011-9089-9.

60 The plan involved deploying $30 billion across a number of financial markets to “buy the dip” – i.e. to acquire assets during periods of downward price pressure with the aim of quickly exiting positions once prices recovered. Despite the board’s opposition, MbS took the decision to King Salman, who overruled the board and issued a statement directing the implementation of the crown prince’s policy. In the final instance, the Saudi central bank was forced to transfer $40 billion of foreign reserves into the PIF to bankroll the crown prince’s investment scheme.

See: Al-Rumayyan, Y. (2022, October 3). Socrates podcast—With the Governor of the Public Investment Fund [Radio Eight]. https://www.youtube.com/@thmanyahPodcasts; Jones, R., Kalin, S., & Said, S. (2023, January 3). Saudi Crown Prince Tangles with Sovereign Wealth Fund Over How to Invest Oil Riches. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-mbs-mohammed-bin-salman-public-investment-fund-11672766494?mod=hp_lead_pos11

61 Dixon, A. D., Schena, P. J., & Capapé, J. (2022). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Between the State and Markets. Agenda Publishing.

62 The Investment Committee found the investment “unsatisfactory in all aspects” and deemed that it posed “public relations risks”.

See: Kirkpatrick, D. D., & Kelly, K. (2022, April 10). Before Giving Billions to Jared Kushner, Saudi Investment Fund Had Big Doubts. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/10/us/jared-kushner-saudi-investment-fund.html

63 Hertog, S. (2010a)

64 Banafe, A., & Macleod, R. (2017). The Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, 1952-2016. Central Bank of Oil. Palgrave Macmillan.

65 Jones, R., Kalin, S., & Said, S. (2023, January 3). Saudi Crown Prince Tangles with Sovereign Wealth Fund Over How to Invest Oil Riches. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-mbs-mohammed-bin-salman-public-investment-fund-11672766494?mod=hp_lead_pos11

66 If successful tech IPOs like Doordash helped its performance in 2020, the Vision Fund reported an $18 billion loss in 2021, a $27.4 billion loss for the financial year ending in March 2022 and a $23.1 billion loss in the April-June 2022 quarter. For the fiscal year ending in March 2023, a record loss of $32 billion was reported.

See: Kharpal, A. (2023, May 11). SoftBank posts record $32 billion loss at its Vision Fund tech investment arm. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/05/11/softbank-full-year-2022-earnings-vision-fund-posts-32-billion-loss.html

Nussey, S. (2020, May 18). SoftBank’s Vision Fund tumbles to $18 billion loss in “valley of coronavirus.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-softbank-group-results-idUSKBN22U0KK

67 Hertog, S. (2019). A Quest for Significance: Gulf Oil Monarchies’ International Strategies and Their Urban Dimensions. In H. Molotch & D. Ponzini (Eds.), The New Arab Urban: Gulf Cities of Wealth, Ambition, and Distress (pp. 276–299). New York University Press; Sims, D. (2015). Egypt’s Desert Dreams Development or Disaster? The American University in Cairo Press.

68 Divakaran, S., Halland, H., Lorenzato, G., Rose, P., & Sarmiento-Saher, S. (2022). Strategic Investment Funds: Establishment and Operations. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1870-7

This publication has been supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. The positions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

Attribution for photo: Rami, “Kingdom Tower – Riyadh, Saudi Arabia”