Introduction

In 2024, student protests spread across North America and Europe agitating against the genocide in Gaza. In the United States, they were massive: tens of thousands of students on nearly 140 college campuses built encampments, staged walk-outs, and occupied buildings demanding their universities to divest or sever ties with Israel. After the April 19 police raid of Columbia University, the tactical repertoire of encampments soon spread rapidly, like the diffusion of shantytown protests against South African apartheid in the 1980s.[1] Academics in Dublin, Oxford, Paris, Berlin, Leiden, Lund, Rome, and Zurich also staged protests against what the global human rights community charge as crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Israeli state against Palestinians.[2]

With few exceptions, the student protests largely failed to win concessions in the United States and mainland Europe. But they partially succeeded in Spain, Ireland, and Norway. Across time, similar campaigns have attempted to pressure institutional investors to divest, such as the anti-apartheid divestment campaigns against South Africa in the 1980s as well as the ongoing fossil fuel divestment campaigns. The former prompted 53 American universities to partially divest from apartheid by 1984, three years before the U.S. Congress overrode President Ronald Reagan’s veto and passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act. At the same time, it failed to move an institution like MIT, which never divested at all despite Massachusetts enacting the first statewide pension fund divestment in the United States, again over the governor’s veto.

Then as now, divergences in outcome can be explained by the interaction of politics, social pressure, and higher education financing. When governing parties are more sympathetic to activist demands, national universities move with them; however private funding channels also insulate tertiary educators from the shifting winds of national political sentiment. This insulation provides some activists an advantage, empowering small liberal arts colleges in particular to become ‘first-movers’ against a national political taboo as long as their alumni donor base are supportive or apathetic. However, it also tends to exact a cost, tilting the university’s selectorate toward the political conservatism of what is typically an older, wealthier, whiter, and more male donor base.

Palestine Protests in the North Atlantic

Responding to the Gaza genocide, student activists in the United States placed particular emphasis on divesting university endowments. For example, a demand from a group called Columbia University Apartheid Divest focused on the university’s financial holdings of publicly traded stocks and bonds implicated in the Israeli occupation. The 2018 and 2020 referenda passed in the undergraduate Columbia College challenged Columbia University to “divest from and/or refrain from investing in” Amazon, Caterpillar, Elbit Systems, and Boeing, and “withdraw assets” from BlackRock’s iShares ETF and Barclays Bank, totaling some 6% of the university’s currently disclosed endowment portfolio.[3] Activists frequently drew parallels between their demands and university ‘responsible investor’ policies against tobacco and private prisons or pointed to past university divestment decisions on South African apartheid or the genocide in Darfur, Sudan.

Student activism has extended beyond the university endowments. Campaigns at MIT and Johns Hopkins focused on research funding channels tied to the Israeli military[4] while organizers at Uppsala University in Sweden, LSE in London, and state universities in California, Michigan, and Georgia have criticized their universities’ institutional partnerships with Israeli universities such as Technion and Hebrew University Jerusalem. Organizers have also asked to rename buildings, increase academic opportunities for Palestinians, and juxtaposed their universities’ inaction on Palestine to their willingness to condemn Russia and sever relationships with Russian higher education institutions over the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Authorities’ response to these protests has been uneven. In the United States, the board of trustees at Union Theological Seminary voted on May 9, 2024 to direct its investment managers to exclude from the school’s modest portfolio “those companies substantially and intractably benefiting from the war in Palestine.” The decision was in keeping with the seminary’s progressive Christian ethos and long-standing responsible investor policies against private prisons, fossil fuels, and weapons manufacturers. Officials at Oregon’s Evergreen State College, the alma mater of the killed activist Rachel Corrie, reached a similar accommodation with their encampment, signing an agreement pledging to divest from “companies that profit from gross human rights violations and/or the occupation of Palestinian territories.”[5] At MIT, a seed fund to encourage MIT collaborations with Lockheed Martin in Israel was not renewed, in a win for the student majority supporting divestment, although the Institute denied the decision had any relationship to activism.

Apart from these examples, however, successes for the American protest movement have been fairly meager. By July 2024, police forces arrested more than 3,000 students, and most encampments were violently destroyed.[6] As of December 2024, no R1 university has committed to a major divestment decision on Israel. (Brown University’s Corporation agreed to vote on a divestment measure in October though the vote failed.) Other agreements with encampments to voluntarily disband, such as those at Harvard, Northwester, and Rutgers-New Brunswick, did not pledge the universities to divest financial assets implicated in the Israeli occupation.

A similarly cold reception can be recorded across France, Germany, and Sweden. In April, French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal accused the student protesters at the Sorbonne and Sciences Po of importing a “North American ideology”. Riot police swiftly cleared encampments at the behest of university authorities. Interim president of the Sorbonne Jean Basseres dismissed protestor demands to review ties with Israeli institutions and partner companies, and a statement by 70 French university presidents in Le Monde affirmed this attitude: “Universities must not be used for political ends.”[7] In Germany, the encampment at Freie Universität Berlin was immediately cleared on May 7 and Humboldt University’s was emptied on May 23. Officials have not met student protests in Frankfurt, Leipzig, Munich and Bremen with any compromise. As the chief security officer at Swiss ETH Zürich said, the university “does not offer a platform for political activism.”[8] In Sweden, the home of a once-formidable social democratic movement, the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions (SUHF) representing 38 universities and colleges issued a statement on May 21 that Swedish educational institutions cannot “take a position on foreign policy issues.” Its flagship universities – in Stockholm, Lund, Uppsala – have applied this principle to Israeli collaborations. The encampment in Lund was violently cleared by police. Authorities at Portugal’s flagship University of Coimbra have similarly not met its student protesters with any compromise.

We can juxtapose these results against more accommodating positions in Ireland, Spain, Norway, Belgium, and Denmark. On May 8, Ireland’s Trinity College Dublin reached an agreement with students to end the encampment and “complete a divestment from Israeli companies that have activities in the Occupied Palestinian Territory and appear on the UN blacklist.”[9] A Sanctuary Fund for Gaza scholars was also created, and a senior dean who led the negotiations thanked the students for their engagement. This was followed by similar solidarity statements by University College Dublin and Irish universities in Limerick and Galway. On May 9, the Conference of University Rectors in Spain (CRUE) representing 76 public and private universities in Spain announced their intention to “suspend collaboration agreements with Israeli universities and research centres that have not expressed a firm commitment to peace and compliance with international humanitarian law” and “strengthen cooperation with the Palestinian scientific and higher education system.”

Successes for the student movement extend beyond Catholic Europe. Amidst protests in Norway, five universities suspended ties with Israeli universities as early as February 2024, as did Finland’s flagship University of Helsinki. In Denmark, the University of Copenhagen announced that it would divest holdings worth a total of about 1 million Danish crowns ($145,810) on May 28. Fund managers committed to ensure institutional investments comply with a United Nations list of companies involved in illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank. The Université Libre de Bruxelles has also joined three other Belgian universities that have ended or committed to review ties with Israeli institutions. As of January 2025, some Dutch and British institutions have also made halting or partial moves to divest from arms manufacturers or suspend overt ties with the Israeli government.

Thus the puzzle: why have student movements succeeded in winning some divestiture demands in parts of Europe but not in America where the student mobilization was arguably more sustained, organized, and militant? In Norway and Denmark, but not Sweden? Belgium but not France? Spain but not Portugal? The student movements largely employed the same tactical repertoire but have yielded different results.

A Theory of Partisan Control

The simplest answer is that institutions of higher education, regardless of their autonomy vis-à-vis their respective governments, are still risk-adverse and follow the winds of different national politics in responding to insurgent social movements from within.

Consider the starkest juxtaposition: the United States versus Spain, Ireland, and Norway. On a demographic level, Spain, Ireland, and Norway have numerically marginal Jewish Zionist populations, and their Catholic or secularized, liberal-Protestant majorities are historically less respondent to Christian Zionist framings than the sizable evangelical community in the United States. The foreign policy preferences of these European voter publics are aggregated by electoral systems more proportional than those in the United States, which is uniquely characterized by strong bicameralism and judicial review, constitutional rigidity, federalism, a presidential executive, and first-past-the-post electoral architecture—what political scientist Lisa Miller has aptly called “veto exceptionalism.”[10]

Moreover the American polity is characterized by substantially deregulated campaign finance or ‘dark money’ compared to the European states[11], measurable pro-Israel bias in the media[12], and a stronger and better-organized Israel lobby (CUFI, AIPAC, etc), which tend to shift policy outcomes to more pro-Israel positions.[13] Evidence of the latter is the 38 US states which have passed anti-BDS laws with the help of interest groups such as the American Legislative Exchange Council.[14] Differences in geopolitical stakes are also important features. Spain, Ireland, and Norway are not major security guarantors to the Israeli government, unlike the United States. US voter demographics, veto exceptionalism, vulnerability to special interest lobbying, and geopolitical reach then shape its political culture. Unlike the liberal and left-wing parties in Europe, both U.S. parties strongly support Israel.[15] On this persistent demographic, institutional, and partisan terrain, it is not surprising that U.S. universities face higher political risks for capitulating to protestor demands perceived to isolate or shame Israel.

What about within Europe? Again, divergent response could be attributed to different national party politics. Two of the first-movers on university divestment (Spain, Norway) are currently led by left-wing coalition governments, which in the European party families tend to be more sympathetic to Palestinian rights.[16] Although Ireland, a third early-mover, had the Christian-democratic party Fianna Fáil in the lead for most of 2024, Ireland’s party system is buttressed by an activist political culture of Irish republicanism historically friendly to the Palestinian national movement.[17] Additionally, Ireland’s incumbent coalition partners Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael faced collapsing support for most of the year and played defense to the left-wing opposition Sinn Féin.[18] These coalition dynamics have produced national-level policy shifts for Palestine. All three countries announced recognition for the state of Palestine in spring 2024, publicly committed to uphold ICC rulings against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and blocked military cargo shipments to Israel over the war on Gaza.

Under the political cover of sympathetic governing coalitions, national universities can concede ground to activists. Thus we can explain the friendly response by universities in Spain under a left-wing coalition compared to the stonewall in Portugal under a centre-right one. In Belgium, where six of the seven governing parties (PS, Vooruit, Groen, Ecolo, Open VLD and CD&V) favored recognizing the Palestinian state, to those universities in France, whose coalition partners ruled out diplomatic recognition of Palestine. In short, left-wing governing coalitions open space for university divestment.

At first glance, Germany appears to be the glaring anomaly. Despite a governing coalition under Olaf Scholz of Social Democrats and Greens, Berlin’s governing mayor Kai Wegner (CDU) introduced a new regulatory law at Berlin’s colleges and universities in April 2024 to criminalize Palestine protests on campus. The federal Education and Research Ministry then launched an investigation against academics who sympathized with the student protestors. But although Germany was ostensibly led by a social democratic chancellor during 2023-2024, the coalition make-or-breaker was the virulently neoliberal Free Democratic Party, while the Christian Democrats (CDU) held a de facto veto. Moreover, the meaningful policy distinctions between party families on an issue domain can blur in the face of a persistent political culture of consensus. Critics often attribute the Zionist consensus of the political establishment in Berlin and the länder to the pathologies of postwar Holocaust memory culture—the German Staatsräson to protect the Jewish state against all criticism.[19] Political culture can, of course, work the other way. Håkan Thörn[20] and Knud Andresen[21] have separately argued that Nordic political culture played a role in the considerable financial support provided by Scandinavian governments for anti-colonial struggles in southern Africa, despite party cycling.

These political cultures are not fixed and can fracture. For example, despite Sweden’s more active record on Palestine, such as the Social-Democratic government’s recognition of the state of Palestine in 2014 (the first in the EU) as well as its history of Israel-Palestine consensus diplomacy[22], the 2010s and 2020s witnessed what Swedish political scientist Maria Owiredu documents as a divergence in party positions on Palestine.[23] The current right-wing government of Sweden Democrats has made a pivot toward Israel, measurable in both its party position and the attitudes of its voters. Thus when governing coalitions are more sympathetic to Palestinian rights, the national universities move with them; when the coalition turns a cold shoulder to Palestine, so do the universities. A remarkably frank statement by the Stockholm University of the Arts in April 2024 illustrates this point:

A public stance and position from SKH, as a Swedish university and public authority, in the war is not possible. However, we condemn all forms of violence, including abuses against the civilian population. In connection with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Swedish government cancelled all Swedish authorities’ cooperation with Russia. With regard to the war between Hamas and Israel, the Government has not taken a similar position.

A Theory of Education Financing

As an Ockham’s Razor explanation of university divestment decisions, the partisan theory does well at explaining the bulk of variation in institutional response. It explains why universities in Norway and Finland folded but not in Sweden. In Spain but not in Portugal. Belgium but not France, and more broadly, peripheral Europe but not America.

The notion that partisanship affects policy outcomes, even those of para-statal institutions like the university, is not new to students of political economy: what impact partisan coalitions have on policy is a worn question, from Andrew Shonfield’s classic Modern Capitalism (1965) to the power resources theory of Walter Korpi and Gøsta Esping-Andersen.[24] However once we examine uneven responses within the same national political context, a simple partisan theory becomes less helpful. Institutions of higher education within the same national context do not respond alike to divestment calls, as the cases in the introduction attest. For example, five universities in Norway severed ties with Israel in the last year, but not the flagship University of Oslo.

Here the political economy of higher education financing carries significant explanatory power. Countries in the North Atlantic have organized the legal and funding structure of higher education quite differently. The United States has adopted a ‘Partially Private’ model, in which both public and private universities uniformly require tuition fees. Some European states created a Mass Public model, while others, such as the German-speaking countries, built a dual-track vocational system and ‘Elite Public’ university model. These ‘three worlds of human capital formation’ are well-known typologies for the scholars of the welfare state and varieties of capitalism.[25]

As products of history, these disparate political economies cast a long shadow over present-day activism. This is because different financing arrangements map on to pressure from philanthropists, students, party leaders, and mass publics. As Charlie Eaton and Mitchell Stevens put it, universities are ‘peculiar’ organizations.[26] They are positionally-central to the institutional order of modern societies, providing “working links between state, market, civil society, and private-sphere organizations.” In their terms, universities are also polysemic, embodying civic, economic, and sacred meanings simultaneously and quasi-sovereign, enjoying a margin of jurisdiction over their own boundaries and internal affairs. For sociologist John W. Meyer, this quasi-sovereignty is articulated in the notion of “the charter” whereby universities certify official knowledge and provide the organizing basis for the Weberian rationalization of education and training. This institutional power to distribute status and opportunity makes the university a crucial site in the reproduction of what Randall Collins once called the “credential society”[27] or Pierre Bourdieu the noblesse d’état.[28]

Yet in terms of quasi-sovereignty, substantial variation exists in the relationship between tertiary educators and the state. In the United States, universities can be incorporated as public non-profit, private non-profit, or for-profit institutions. In Sweden and Belgium, by contrast, they are almost always public institutions. Regardless of legal status, universities raise money from various sources, which insulate or expose them to different shades of partisan or state interests. They can acquire revenue from (1) financial assets that generate liquid income – what is often called an endowment, (2) land or property rents, (3) tuition from students, who may pay from a menu of family home financing options or borrow with government-subsidized loans, (4) state grants, either per-student or lump-sum, (5) gift philanthropy from benefactors and alumni, (6) state research funding, such as from the U.S. National Science Foundation, and even (7) bond issuance. Each of these sources can be conceptualized as dials that move a central dial of the university’s exposure to state pressure.

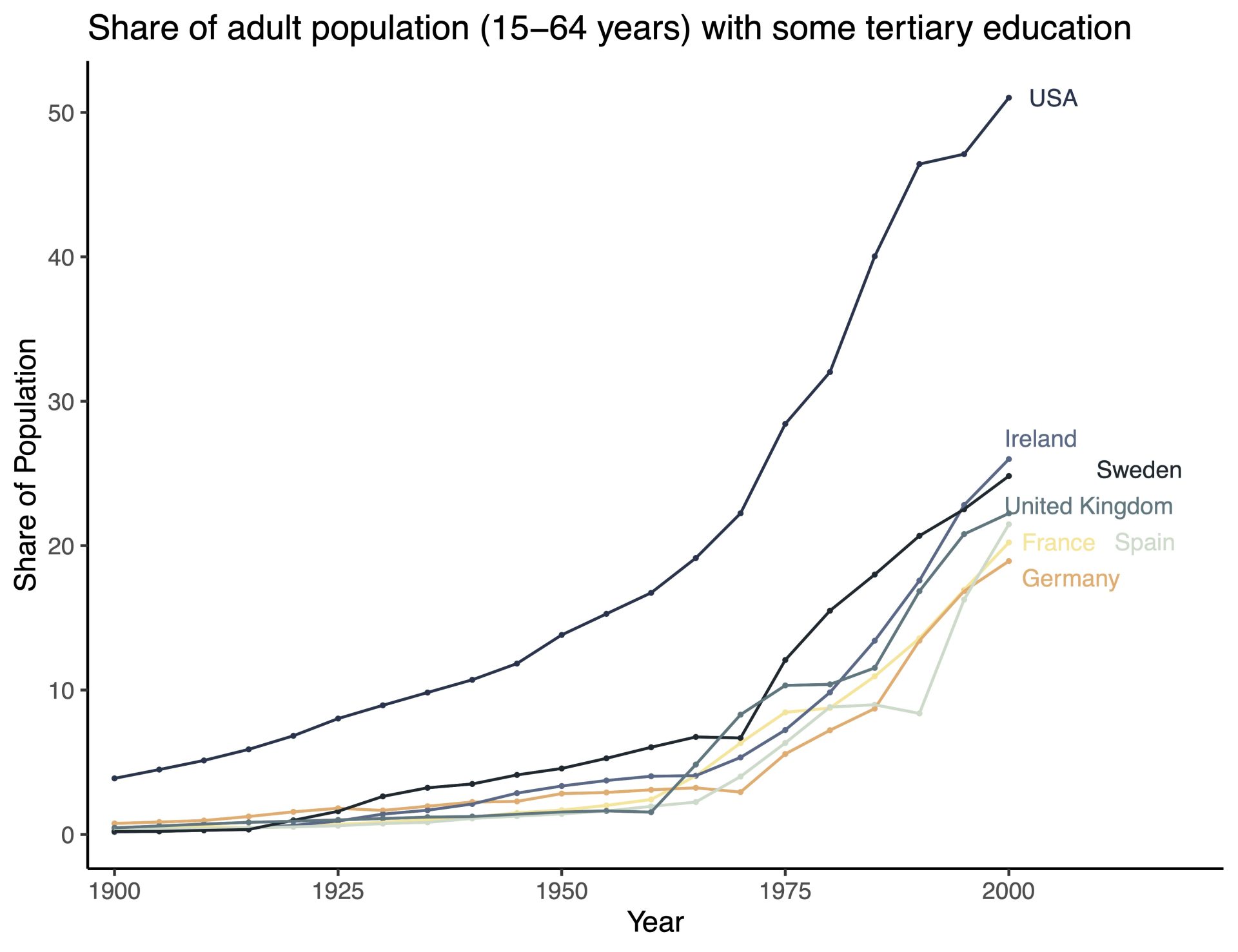

What determines how these dials are set? As Iversen and Stephens show, higher education systems often cluster cross-nationally on several indicators of state involvement—clusters they label Social Democratic, Christian Democratic, and Liberal and which they attribute to historical differences in the organization of capitalism and electoral politics in the mid-late 19th century.[29] Other studies of the political economy of higher education financing similarly start the causal story behind the setting of the dials in the postwar era.[30] Iversen and Stephens, for instance, assert that “the three worlds of welfare and publicly financed skill formation were not clearly detectable as of 1950.” Indeed, the historic expansion of higher education, what education scholar Martin Trow called the ‘great transition’[31], is a post-war phenomenon.

Find Lee and Lee citation at [32]

Financing Higher Ed: The Political/Policy Trilemma

As Ben Ansell’s work has developed, higher education financing has required policymakers to balance the scale of enrollment, the degree of subsidization, and the public cost of higher education—what he calls a ‘trilemma.’ When public cost is held constant, a country faces a tradeoff between the first two. Partisan preferences over these trade-offs are derived from their unequal fiscal burdens. Unless access to higher education is made independent of income, allocating public resources to universities is fiscally regressive, benefiting the children of a rich elite with the taxes of a poorer majority. However if enrollment is expanded to a mass level, regressivity is diluted, and higher education subsidies begin to look more like standard redistributive public spending. Accordingly, at low levels of development, conservative parties favor channeling resources to universities (and by extension, their wealthier constituencies). Left-wing parties, meanwhile, tend to prefer building out primary and secondary schooling, which benefits their lower-income base. As tertiary enrollment becomes accessible to the masses, the parties swap positions. Left-wing parties embrace higher subsidization and mass enrollment while the right tries to limit public grants and equal access. The degree to which universities rely on state funding and find themselves susceptible to either partisan pressure or private donor pressure is thus a function of the long-term balance of partisan power.

There are examples, however, where the left-right interplay was flummoxed. We can see this in countries with a historically strong Christian Democratic presence or federalist constitutional constraints. Take Germany as an example. There, the roots of a vocational training system were introduced at the turn of the 20th century by an authoritarian state.[33] Access to universities was jealously restricted by the sub-national länder. A dual-track education system eventually calcified during postwar years of Christian-Democratic rule, which prioritized cross-class compromise between unions and employers as part of what Kees van Kersbergen calls a “politics of mediation.”[34] As the länder controlled the admissions process and remained hostile to raising funding or enrollment, and as the unions acquired interests in the dual-track system, so did the left-wing parties; the SPD in Germany remained historically “unwilling to countenance expansion of a system where few working-class students gain access.”[35]

Despite a shared lineage as providers of an elite distinction[36], the tertiary education sectors in the United States and Europe were on different footing before they entered the age of mass enrollment. In the United States (and to the lesser degree the United Kingdom) large endowments, tuition-charging, philanthropy, and alumni fundraising practices developed in the late 19th century under a “free money” ideology, to use a term from an excellent new book by Bruce Kimball and Sarah Iler.[37] The endowment-centric ideology flourished best in monetary and partisan conditions specific to the United States. With the threat of socialist or social-democratic policy influence low, rights to the income of financial assets guaranteed, and macro-economic conditions stable, the endowments of elite universities amassed enormous holdings. Under these conditions, the universities shaped the transition to mass enrollment in such a manner as to preserve (and diffuse) their private funding practices across the country. For instance, ‘free money’ ideology was incorporated into the policy prescriptions of the General Education Board, Carnegie and Ford Foundations. On the European continent, the upheaval of world wars, hyperinflation, and the rise of communism and social democratic parties meant that private philanthropic foundations in the 20th century faced uncertainty and frequent decline.[38] In peripheries such as Ireland, the Mediterranean and Scandinavia, capital markets and industry were not deep enough to generate the titanic personal wealth that endowed the British and American ivory towers at the turn of the century. These factors guaranteed that Europe’s transition to mass higher education after the war would rely on heavy state financing.

Later, the same elite Anglo-American institutions were also positioned to co-produce and benefit from the shift to financialization. Under their influence, Congress and regulators made aggressive forms of endowment accumulation more profitable. In the 1970s, Congress loosened constraints on junk bonds and other debt vehicles, cut income and capital gains taxes, and passed legislation to allow institutional investors to hold more equities in their portfolios. In 1984, Congress also eliminated a two percent excise tax on university endowment investment returns. Outside the Capitol, the primacy of endowments and donor-giving as metrics for university excellence was embedded in the formulas by which universities were ranked by the US News & World Report and Times Higher Education. Rankings further attuned university growth strategies to the importance of accumulating large reserves and encouraging donor philanthropy. Indeed, the intimate ties between the university social environment and asset management capitalism, in particular venture capital, private equity, and hedge funds, constitute what Charlie Eaton calls in his book Bankers in the Ivory Tower (2022) the ‘high-finance advantage.’

Student Loans and Defense Dollars

Of course, alumni philanthropy and endowments were not the only means by which higher educators expanded. Today, American universities are a top employer of lobbyists on Capitol Hill.[39] Josh Mitchell[40] and Susan Mettler[41] separately detail their role, along with financier partners, in shaping a student loan industrial complex. With the post-realignment Republican party unwilling to fully subsidize education via universal block grants beyond the G.I. bills, Congress created a loan-financing regime to expand enrollment and make education accessible to the masses. Subsidized credit became particularly important after more ambitious public funding schemes following the 1965 Higher Education Act failed to pass conservative opposition.[42] During the Cold War, universities with strong science and technology faculties, such as MIT, Stanford, and Georgia Tech, could also supplement their endowment growth by tying themselves to the national security apparatus and pursuing substantial government research funding.[43]

This history casts a long shadow on divestment activism. During the transition to mass higher education, universities in the United States and United Kingdom not only protected their philanthropic foundations from nationalization but entrenched and diversified existing financial models. In preserving private funding channels, American and British universities retained greater independence from the political parties of the day but exposed themselves to the political conservatism of their own donor base. Historically, the alumni donor base for the prestigious R1 schools in the U.S. or Russell Group in the U.K. tend to be older, wealthier, whiter, and more male than their respective student bodies and the national electorate. As the endowment portfolios of the deep pocketed universities became larger and more complex—especially in the 1980s with asset securitization enabled by the loosening of financial rules—this conservatism became more pronounced.

Insulation from state pressure did not lead all US and UK higher education providers to become conservate, of course. Some schools developed a “social circuitry of activists” among alumni and students, who cultivated campus leaderships and donor networks more sympathetic to social activism. This encouraged the development of institutional reputations for being progressive, anti-racist, or otherwise socially conscious. Notable here are liberal-arts colleges, seminaries, historically black colleges and universities, and women’s colleges. This factor can help explain why schools like Evergreen State College and Union Theological Seminary were willing to make public announcements against the Israeli occupation prior to national legislation, similar to Brown University and Vassar College’s decisions in an earlier era against South African apartheid.

Continental Europe followed a different path, with attendant consequences for the protests against the Gaza genocide. There, as mentioned, university philanthropic funds were destroyed or nationalized earlier in the 20th century, and the purse strings of higher education were subsumed under the state.[44] Downstream of that process, university divestment politics become synonymous with partisan control. Where the political objectives of European student movements have aligned with national political party sentiment, the universities are more likely to capitulate to student demands. They have also been more likely to capitulate swiftly and in a unified, clustered cascade than is the case in the United States.

Policy Implications and Conclusions

Two complementary variables, both products of history, explain how higher education institutions respond to activist demands: (1) the degree to which they are subjected to partisan-cum-state control and (2) institutional funding structures. The Palestine protests on campuses in spring 2024 serve as an affirming test case for these claims.

US endowments were originally created, at least in part, to shield elitist institutions from political interference, such as the whims of state legislatures. For instance, Unitarian Harvard and Congregationalist Yale had spats over the curriculum with their respective state legislatures up to the 1840s, after which they solicited private sources of funds in large enough amounts to insulate themselves from lawmaker influence for the remainder of the century. The acquisition of private donor funds came at its own cost: It exposed university decision-makers to the preferences of the donors. In the case of early 19th century Yale and Harvard, that donor class was the New England business elite. Today, it’s a global network of wealthy men, such as MAGA billionaires Kenneth Griffin or William Ackman.

On one hand, the trend in the United States tilted the universities’ selectorate toward the political conservatism of an older, richer, whiter, and more male donor base. It also naturalized an economic order in which investing according to profit incentives is interpreted as an apolitical act, whereas divesting on the basis of moral demands is understood as an unwelcome political intervention. We can juxtapose this to the more morally alert investment strategies of pension and sovereign wealth funds in Norway. On the other hand, American higher education preserved a heterogeneity of institutional forms and funding structures into the age of mass enrollment, leaving open the possibility that some donor networks—for instance those at progressive liberal arts colleges and historically black institutions—could provide cover for an institution to accommodate its student activists, even against the currents of national partisan consensus. Thus some of the American colleges can be first movers. In Europe, as both the peripheries and core transitioned to mass higher education, the purse strings of the old elite universities were subsumed under the state. Under these conditions, student protests can still be effective at driving divestment. However, efficacy depends on students forcing their priorities directly into the governing party coalitions, not by a ‘long march through the institutions’ that conquers the universities first and the government second.

Disparities in the funding of higher education shape not only the extent of university autonomy from partisan control, but also how social movements relate to the university as an arena of contestation. In Europe, activist pressure more frequently revolves around the school’s institutional rather than financial relationships with complicit entities. This reflects the fact that university endowments in Europe are meager or absent, and European university finances are more widely recognized as tethered to the state. In the United States, in comparison, where universities are often perceived to be autonomous institutional and financial actors, activists lay intensified claims on them—and contest the universities’ endowment and exterior funding channels. This dynamic is reinforced by the symbolic and physical sequestration of American student and campus affairs from urban life, as manifested for example in the geographic layout of land-grant campuses, the housing structure (dorms, Greek life, on-campus apartments), and alumni and student culture.

This leads to a final insight pertinent to protests against the genocide in Gaza. In continental Europe, universities’ ties to states can be a problem and an opportunity. Where European states are more responsive to democratic pressure than Anglo-American varieties—a virtue born of their more proportional political institutions and institutionally-supported working class movement—it is possible governments can be swayed and with them, the national universities. In the United States and United Kingdom, student activists face not just the antipathy of the parties but an additional opposition: the donors.

This insight serves as a rejoinder to a theme of university institutional design—discernable in the anti-state sentiment of Enlightenment education theorists such as Mirabeau, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and J.S. Mill—which asserts that the ideal university is the one capable of funding itself independently from the legislature. In Humboldt’s words, the financially dependent university degenerates into a “mere institute for the use of the state.” Independent financing he argued insulates the university from politics and makes it best able to provide a fertile ground for an emancipated civil society and the moral development of the whole person (“Bildung”). He even resigned in disappointment after failing to secure a land-grant from the King of Prussia for his new university in Berlin. Instead, we should understand that universities always contend with different selectorates of various sizes and persuasions that impose political demands, whether by party-dominated legislatures or private donors. In fact, institutional reliance on the state can serve as an advantage to progressive mass movements as long as the state itself is democratic.

[1] Soule, Sarah A. 1997. “The Student Divestment Movement in the United States and Tactical Diffusion: The Shantytown Protest.” Social Forces 75 (3): 855–82.

[2] See for example materials from the ongoing South Africa v. Israel case in the International Court of Justice. Also Amnesty International, “‘You Feel Like You Are Subhuman’: Israel’s Genocide Against Palestinians in Gaza.” December 5, 2024. Human Rights Watch, “Extermination and Acts of Genocide Israel Deliberately Depriving Palestinians in Gaza of Water.” December 19, 2024. Forensic Architecture, “A Cartography of Genocide: A Spatial Analysis of the Israeli Military’s Conduct in Gaza since October 2023.” October 25, 2024.

[3] Tooze, Adam. 2024. “Chartbook 279: Columbia University’s ‘Crisis’ – a Political Economy Sketch Map.” Substack newsletter. Chartbook (blog). April 26, 2024.

[4] See MIT Coalition for Palestine. MIT Science Against Genocide report (December 10, 2024).

[5] Sowersby, Shauna. 2024. “Evergreen Signs Agreement with Students to Move toward Divesting from Companies Profiting in Gaza.” The Olympian. May 3, 2024.

[6] The New York Times. “Where Protesters on U.S. Campuses Have Been Arrested or Detained,” May 2, 2024.

[7] Le Monde. “L’appel de 70 présidents d’établissements d’enseignement supérieur : « Les universités ne doivent pas être instrumentalisées à des fins politiques »,” April 25, 2024.

[8] ETH Zurich Staffnet. “‘ETH Zurich Is Not a Platform for Political Activism.’” May 8, 2024.

[9] Carroll, Rory, and Rory Carroll. “Trinity College Dublin Agrees to Divest from Israeli Firms after Student Protest.” The Guardian, May 8, 2024.

[10] Miller, Lisa L. 2023. “Checks and Balances, Veto Exceptionalism, and Constitutional Folk Wisdom: Class and Race Power in American Politics.” Political Research Quarterly 76 (4): 1604–18.

[11] Oklobdzija, Stan. 2024. “Dark Parties: Unveiling Nonparty Communities in American Political Campaigns.” American Political Science Review 118 (1): 401–22.

[12] Jackson, Holly M. 2024. “The New York Times Distorts the Palestinian Struggle: A Case Study of Anti-Palestinian Bias in US News Coverage of the First and Second Palestinian Intifadas.” Media, War & Conflict 17 (1): 116–35.

[13] Mearsheimer, John J., and Stephen M. Walt. 2007. The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. See also Pappe, Ilan. 2024. Lobbying for Zionism on Both Sides of the Atlantic. Simon and Schuster.

[14] For a good treatment of ALEC, see Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander. 2014. “Who Passes Business’s ‘Model Bills’? Policy Capacity and Corporate Influence in U.S. State Politics.” Perspectives on Politics 12 (3): 582–602.

[15] Rynhold, Jonathan. 2023. “Partisanship and Support for Israel in the USA.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Israel, edited by P. R. Kumaraswamy, 1–31. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

[16] “Positions of EU Leaders on Israel-Palestine Dispute (Track Record).” 2024. Eumatrix.

[17] Browne, Brendan Ciarán. 2024. “Reading Irish Solidarity with Palestine through Ireland’s ‘Unfinished Revolution.’” Journal of Palestine Studies 53 (1): 92–103.

[18] Finn, Daniel. “Brittle Opposition.” NLR/Sidecar, December 05, 2024.

[19] Jewish Currents. “Bad Memory” [Deutsch]. Spring 2023.

[20] Thörn, Håkan. 2019. “Nordic Support to The Liberation Struggle in Southern Africa-Between Global Solidarity and National Self-Interest.” Southern African Liberation Struggles, 1.

[21] Andresen, Knud. n.d. “Between Goodwill and Sanctions: Swedish and German Corporations in South Africa and the Politics of Codes of Conduct.” In Apartheid and Anti-Apartheid in Western Europe, 25–48. Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

[22] Levitan, Nir. 2023. Scandinavian Diplomacy and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Official and Unofficial Soft Power. London: Routledge.

[23] Owiredu, Maria. 2024. “Sveriges Politiska Partieroch Israel-Palestinafrågan: En Analys Av Svenska Partiers Agerande 2006–2021.” PhD Thesis, Linnaeus University Press.

[24] On education policy and financing, Carles Boix, Marius Busemeyer, and Ben Ansell have also examined the impact of partisan coalitions.

[25] See Iversen, Torben, and John D. Stephens. 2008. “Partisan Politics, the Welfare State, and Three Worlds of Human Capital Formation.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (4–5): 600–637.

[26] Eaton, Charlie, and Mitchell L. Stevens. 2020. “Universities as Peculiar Organizations.” Sociology Compass 14 (3): e12768.

[27] Collins, Randall. 1979. The Credential Society: An Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification. New York: Academic Press.

[28] Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998. The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power. Stanford University Press.

[29] Iversen, Torben, and John D. Stephens. 2008. “Partisan Politics, the Welfare State, and Three Worlds of Human Capital Formation.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (4–5): 600–637.

[30] See for instance Ansell, Ben W. 2010. From the Ballot to the Blackboard: The Redistributive Political Economy of Education. Cambridge University Press. Busemeyer, Marius R. 2014. Skills and Inequality: Partisan Politics and the Political Economy of Education Reforms in Western Welfare States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Eaton, Charlie. 2022. Bankers in the Ivory Tower: The Troubling Rise of Financiers in US Higher Education. University of Chicago Press. Stevens, Mitchell, and Michael W. Kirst. 2015. Remaking College: The Changing Ecology of Higher Education. Stanford University Press.

[31] Trow, Martin. 2010. Twentieth-Century Higher Education: Elite to Mass to Universal. JHU Press.

[32] Data source: Lee, Jong-Wha, and Hanol Lee. 2016. “Human Capital in the Long Run.” Journal of Development Economics 122 (September):147–69.

[33] For a canonical study, see Thelen, Kathleen. 2004. How Institutions Evolve: The Political Economy of Skills in Germany, Britain, the United States, and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

[34] Kersbergen, Kees van. 2003. Social Capitalism: A Study of Christian Democracy and the Welfare State. London: Routledge. Kersbergen, Kees van, and Philip Manow. 2009. Religion, Class Coalitions, and Welfare States. Cambridge University Press.

[35] Ansell, Ben W. 2011. “9. Humboldt Humbled? The Germanic University System in Comparative Perspective.” In Social Policy in the Smaller European Union States, edited by Gary B. Cohen, Ben W. Ansell, Robert Henry Cox, and Jane Gingrich, 215–36.

[36] At the dawn of the 20th century, universities in all OECD countries were competing providers of an elite distinction, serving less than 3% of the graduating age cohort from secondary schooling. Many universities held assets such as land or company stock and relied on wealthy benefactors to cover expenses.

[37] Kimball, Bruce A., and Sarah M. Iler. 2023. Wealth, Cost, and Price in American Higher Education: A Brief History. JHU Press.

[38] For a useful typology of Europe’s philanthropic funding regimes, see Anheier, Helmut, and Siobhan Daly. 2006. The Politics of Foundations: A Comparative Analysis. Routledge.

[39] OpenSecrets, Federal Lobbying by Industry, 1998-2024.

[40] Mitchell, Josh. 2021. The Debt Trap: How Student Loans Became a National Catastrophe. Simon and Schuster.

[41] Mettler, Suzanne. 2014. Degrees of Inequality: How the Politics of Higher Education Sabotaged the American Dream. Basic Books.

[42] Student debt, infamously, is the only class of debt U.S. borrowers cannot escape by declaring bankruptcy.

[43] Leslie, Stuart W. 1993. The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford. Columbia University Press.

[44] In Austria for instance, the monarchy repeatedly attempted to appropriate foundation assets to fill budget gaps at various times from the 17th to 19th centuries and then made private university foundations government institutions in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Image Attribution: عباد ديرانية, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This publication has been supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. The positions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.