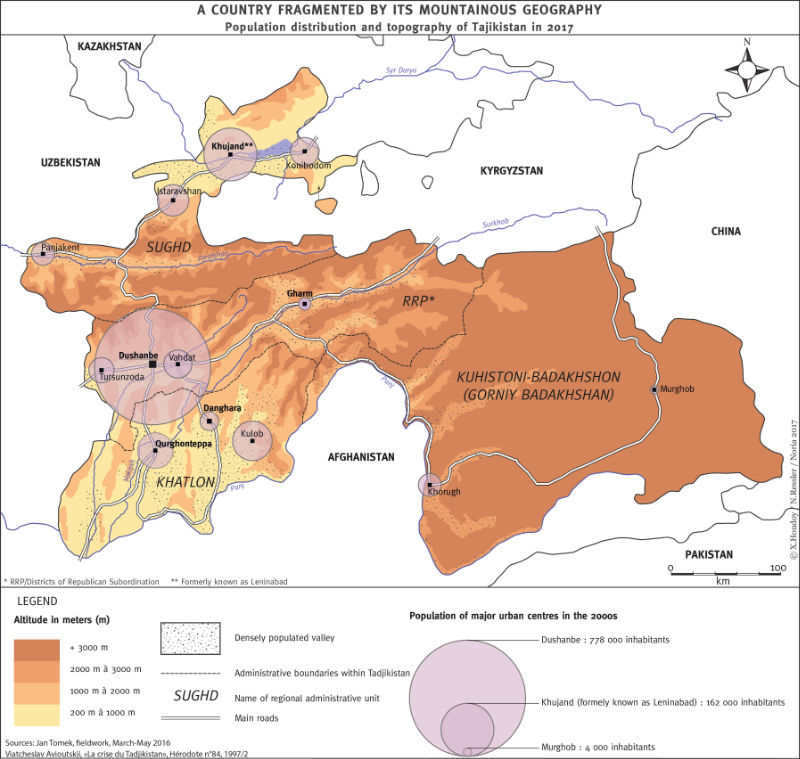

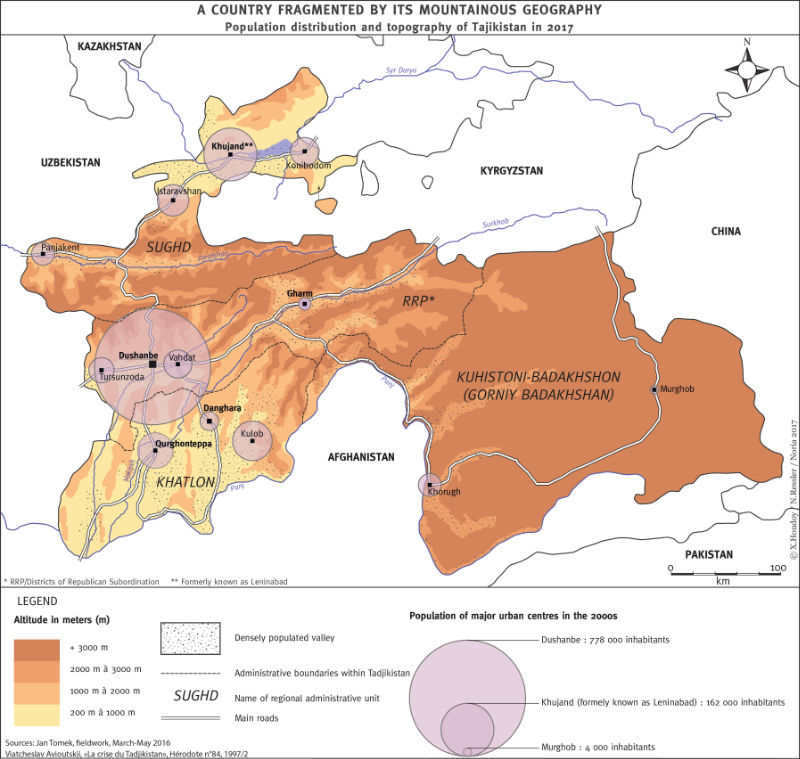

Parts of Central Asia – a region where authoritarian rule has been the norm since the end of the Soviet Union – are liberalising, albeit modestly. In Uzbekistan, this has been the case since the passing of President Karimov in 2016. As for Kyrgyzstan, it experienced its first formal democratic transfer of power after the October 2017 presidential elections. Tajikistan, however, seems to go against regional trends and is steadily sliding towards consolidated authoritarianism. For much of the 2000s, this small landlocked country, located at the junction of Asia’s highest mountain ranges

1, enjoyed a considerable degree of political pluralism (second only to Kyrgyzstan), and the highest degree of media freedom in all Central Asia.

2

The end of this brief democratic opening coincides with the unravelling of the post-civil war power-sharing agreement. Tajikistan is still recovering from the bloody civil war of 1992-1997, which led to the loss of 60,000 to 100,000 lives and to the displacement of approximately 650,000 Tajikistanis.

3

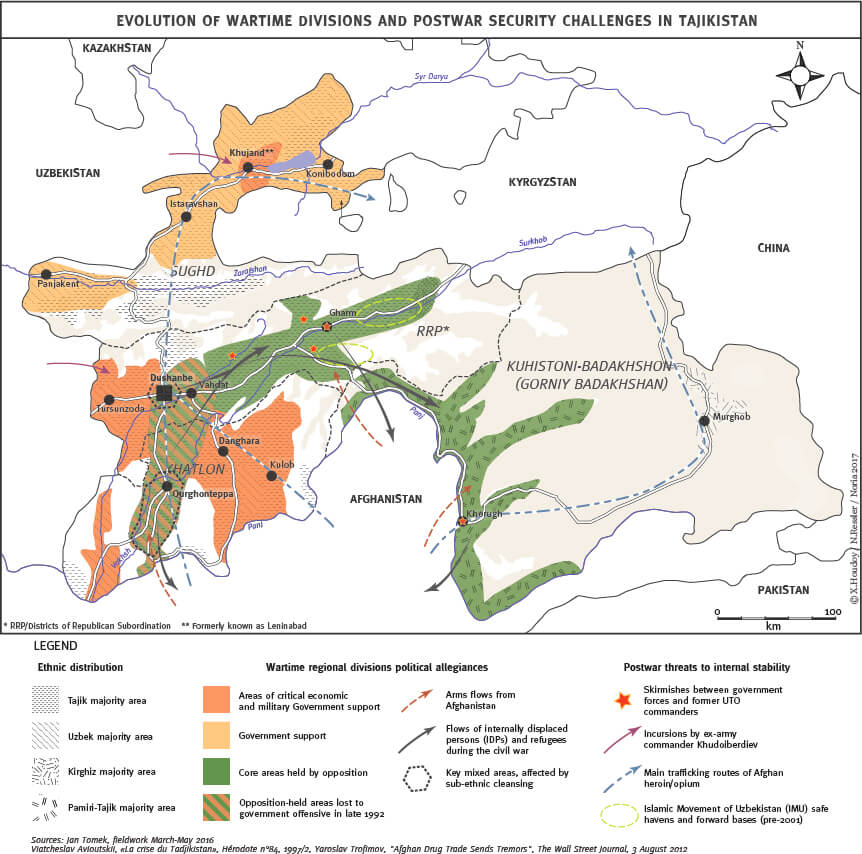

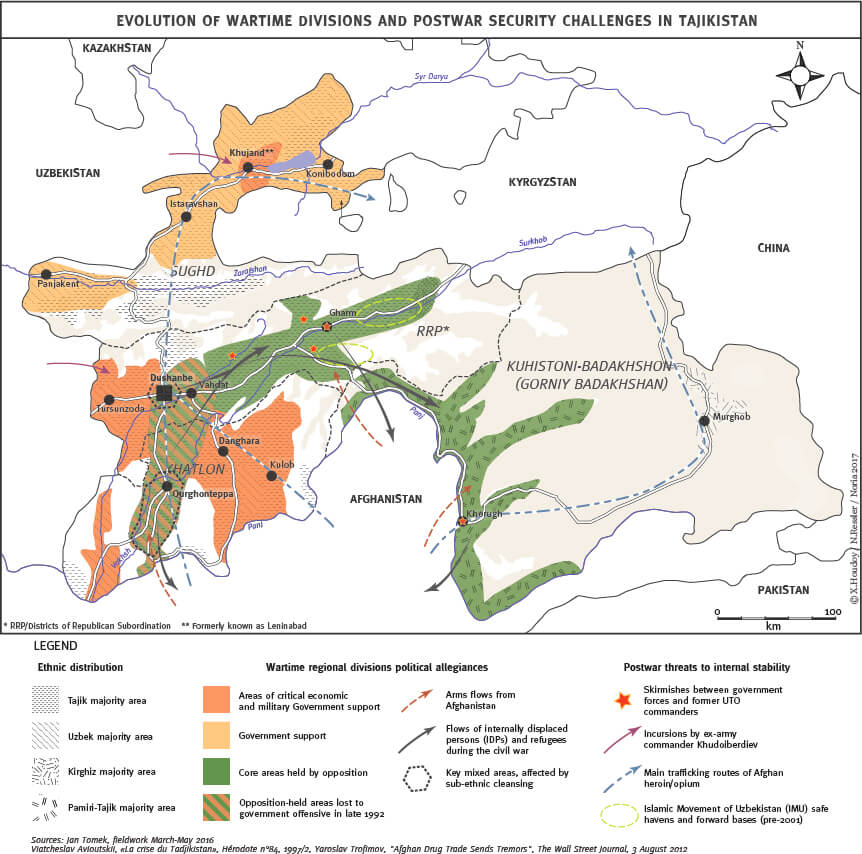

The conflict pitted regionally-based interest groups against one another in a struggle both for access to state resources and over competing ideological visions for the country’s future. The pro-government factions, drawn from the ranks of the Soviet-era bureaucratic elite and backed by the traditionally dominant lowland-dwelling Tajikistanis in the north and south of the country, were bent on defending the post-independence status quo. Independence had been thrust upon the Central Asian republics unexpectedly in 1991. Tajikistan’s political leadership, having with great reluctance shouldered their emancipation from Moscow, aimed to mitigate for these changes by preserving a degree of continuity with the Soviet era. This meant maintaining strong state control over the lives of the country’s citizens, especially in the economic, religious and national identity realms.

The chief challenger of the status quo was the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), a loose coalition of Tajik nationalists, moderate Islamists, liberal democratic activists and advocates for greater self-determination for the linguistically and confessionally distinct Gorno-Badakhshan region. The Tajik opposition’s aims were the relinquishment of Tajikistan’s Soviet legacy and a partial reorientation of the country’s political ties from the post-Soviet space towards the wider Persian-speaking world. The UTO was backed by the inhabitants of the rugged mountainous regions of central and eastern Tajikistan, by their regional-identity-preserving kinsmen in the cotton-rich southern lowland Qurghonteppa region, relocated there by force during the Stalinist era, and also by the liberal-minded parts of the urban intelligentsia.

The armed conflict was the culmination of a series of domestic crises, starting with the February 1990 riots (triggered by the rumoured relocation of Armenian refugees to Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital). Large-scale opposition protests in mid-1991, in reaction to the failed coup in Moscow, culminated in the resignation of then President Mahkamov and the outlawing of the Communist party. The emboldened opposition took to the streets again the following year, after the dismissal of the Badakhshani minister of interior Navzhuvanov.

4 Firearms found their way into the hands of the participants of opposing rallies and town square sit-ins and violence eventually broke out. The fighting then spread to most parts of the country, as returning protesters and counter-protesters alike brought belligerent zeal to their own respective home provinces. The first months of the war were also the most violent. A pro-government paramilitary group known as the Popular Front initiated “sub-ethnic” cleansing, singling-out civilians on the basis of on their regional origins, first in the mixed Qurghonteppa region, only to bring this tactic over later to the capital. Tajikistan’s neighbours and other regional powers played an important role in both the civil war and the eventual peace talks. The government received fluctuating degrees of support from the Russian Federation and neighbouring Uzbekistan, while Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance

5 supplied the UTO with arms, training and logistical support. As for Iran, it provided the opposition with ideological backing, most notably supporting the now-banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), the UTO’s most powerful constituent.

The article maps the peace process and post-war power-sharing in Tajikistan. It shows how the post-conflict political order unravelled, with the creeping monopolization of the executive branch by pro-government forces squeezing out all meaningful opposition. Nevertheless, despite the political and economic challenges and persistent regional divisions, no renewed larger-scale armed conflict has taken place in Tajikistan so far.

6

The peace process and power sharing : shaking the traditional inter-regional power balance

The end of the war in Tajikistan can be attributed to coordinated international efforts to bring the warring sides to the negotiating table. This reflected both new security developments in the region and an alignment of national interests among key regional players. This was most notably the case of Iran and Russia, brought together by the latter’s bid to complete the construction of a nuclear power plant in the southern Iranian city of Bushehr. In early 1996, Russian foreign minister Kozyrev had been replaced by the more proactive Yevgeny Primakov, an expert in the Middle East, and Russia’s “soft underbelly” to the south regained prominence in Moscow’s policymaking. In Afghanistan just next door, the rapid northward advances of the Taliban after the fall of Kabul that same year allowed for some Russian arm twisting of the Northern Alliance, compelling the latter to stop supplying the UTO with weapons.

7 External interference thus ensured that none of the two warring parties in Tajikistan could secure a decisive victory and that the only conceivable outcome would be a negotiated peace deal.

“Track Two” diplomacy laid the groundwork for official meetings in Moscow, Tehran, Islamabad and other regional capitals. These meetings set the modalities for an indefinite ceasefire, the return of refugees and internally displaced persons, and the demobilization of the “armed opposition” or their incorporation into the national army. However, a serious shortcoming of those peace talks and the peace process at large was that they excluded very early on some of the major regionally-based interest groups. This was notably the case of the more hard-line Islamists within the UTO and of the largely pro-government Uzbek minority. Conspicuously side-lined was also the historically dominant Leninabad Region in the north of the country, virtually unscathed by a civil war roaring at a safe distance two high mountain chains away, which gradually lost its political dominance to the southern Kulob Region.

8

These exclusions led to several violent attempts to derail the peace process. The most high-profile case was a series of armed incursions by rogue ex-army commander Khudoiberdiev, a member of the country’s sizeable Uzbek minority, carried out from neighbouring Uzbekistan in 1996 and 1998. Furthermore, in remote parts of central and eastern Tajikistan, a handful of former UTO commanders kept engaging in skirmishes with government forces until as late as the mid-2010s.

9

In light of this limited inclusiveness, the civil war and subsequent peace process did little to resolve the structural causes behind the original outbreak of hostilities, namely weak state capacity, extreme regional imbalances in access to resources, a regionally fragmented and weakly consolidated national identity, and chronic side-lining of both Islamist and liberal voices. The only deep change the civil war brought about was the southward shift of the inter-regional power balance. This change had manifested itself in the replacement, half way into the war, of Leninabadi President R. Nabiev by Emomali Rahmon, the current incumbent.

The latter had worked as a chairman of a collective farm in the Danghara District of the southern Kulob Region, half-way between Dushanbe and the city of Kulob itself. The appointment of then inconsequential and seemingly weak Rahmon was a compromise between the economically and politically-dominant North and the high command of Tajikistan’s armed forces, which traditionally hailed from Kulob. Leninabad’s isolation from the rest of the country, the lack of more active Northern involvement in the civil war and the South’s brandished authenticity as the home of true Tajiks (as opposed to the more “Uzbek-flavoured” North), all contributed to this side-lining.

The implementation and the erosion of the power-sharing deal : early red flags

The post-war arrangement granted 30% of the seats in the executive branch to the UTO. The necessity to “free up” the promised percentage served as an excuse for the newly dominant southern regional grouping to remove from positions of power the regional cliques that had been excluded from the peace negotiations.

10 The ones bearing the brunt were the northern Leninabadis and the Uzbeks, but also to some extent non-Danghari Kulobis. Last but not least, none of the key ministries were ceded to former UTO commanders; they were all securely in the hands of the ascendant Southern political elites.

11 Such repudiations from the executive branch, which the government could easily blame on exogenous constraints, like the implementation of an internationally-brokered peace agreement, were a sign of things to come.

The post-civil war power-sharing mechanism itself suffered an early blow in 2000, when the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund pledged tens of millions of dollars of post-conflict economic assistance to Tajikistan under the condition that government spending will be noticeably slimmed down. Ministries, government agencies and state companies were thus disbanded or merged, in a way that consistently targeted those positions held by the opposition, rather than by the dominant, essentially Southern, power group.

12

Disbanding existing ministries proved to be too limited of a tool in reshaping the post-war power balance. The post-conflict compromise was further undermined by a de-legitimization campaign against non-co-opted high-ranking members of the UTO still holding quota-related positions of power. The most common approach was the use of flimsy disciplinary or criminal charges against prominent ex-UTO commanders. This tactic was used in 2003 against Shamsiddin Shamsiddinov, deputy-chair of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT)

13 and, in 2006, against Mirzo Ziyoev, minister of emergency situations.

14

The slow pace of this marginalization suggests that Southern political elites had learnt from their Northern predecessors’ mistakes. Some experts claim that the escalation of violence at the start of the civil war in the early 1990s was set off by a full-on attack on the opposition by overconfident Northern political elites.

15 The Southerners’ slow and cautious eviction of the opposition proved to be a more successful strategy. This explains why the IRPT was only outlawed in 2015, first by parliamentary vote and later again by a supreme court ruling. What begs an explanation, however, is the Islamic Renaissance Party’s surprising complacency.

A new political and socio-political reality : the constriction of the ruling circle and the narrative of securing peace for Tajikistan

Indeed, besides a handful of prominent exceptions, there does not seem to have been any serious backlash against the slow monopolisation of the Tajikistani state apparatus by an increasingly narrow regional clique. This self-restraint has been a striking feature of the post-civil war

status quo in Tajikistan.

16 It is true of the opposition in Tajikistan, but also of the bulk of the country’s adult citizenry, among which the desire to maintain peace seems to have trumped almost all other political demands. The still vivid memory of the anti-government protests in Shahidon Square in 1992, which set off a chain of events culminating in armed conflict, precludes any large-scale display of public discontent in an increasingly authoritarian state.

Concurrent elections in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in 2005 were illustrative of the political apathy of Tajikistani citizens to cases of vote-rigging, while the same allegation in Kyrgyzstan led to the toppling of the regime.

17 On a wider regional scale, the civil war in Tajikistan is used by autocratic regimes like Uzbekistan as a cautionary tale: it allows to present peace as incompatible with real political competition, let alone the legal existence of Islamist parties.

The people currently in power in Tajikistan seem to understand this deterrent effect very well. Moreover, the official narrative frames peace in Tajikistan as solely the President’s achievement. By imposing this narrative, Rahmon’s inner circle indirectly acknowledges that it can no longer simply rely on the fading recollections of Tajikistani citizens. Early on, primary school textbooks in post-war Tajikistan had included sentences like “We are fighting for peace”.

18 More recently, a December 2015 law passed by the Parliament declared the current President “Founder of Peace and National Unity, Leader of the Nation” – local media outlets failing to write an unabridged version of this official title each time Rahmon is mentioned face hefty fines.

19 As a legitimizing device, memories of the civil war and its atrocities had given way to a broader ideological narrative, hinging on the myth that Emomali Rahmon single-handedly ended the civil war in Tajikistan. Many state-commissioned posters and banners throughout the country convey this notion more or less explicitly.

However, these efforts might prove insufficient given Tajikistan’s demographic trends. While 7% of the population is between 18 and 25 years of age, a whopping 40% is under the age of 18.

20 These cohorts have no personal recollections of the war of the 1990s. With time, the proportion of Tajik citizens with some degree of political consciousness but lacking the political self-restraint stemming from a first-hand experience of civil strife will increase dramatically. This will serve as a test for the credibility of the government’s one-sided narrative of peace-making, and could have a potentially destabilizing effect on the domestic situation – especially if the flow economic migrants, which is both crucial for Tajikistan’s remittance-dependent economy and a social and political “safety valve”, gets disrupted. The most important stabilising factor in Tajikistan’s political culture is thus slowly fading away. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’s relative success in recruiting young Tajik migrant workers in Russia for their war effort in Syria and Iraq can serve as a red flag.

21

Conclusion

Contrary to the prevailing official narrative, putting an end to the civil war in Tajikistan would have been hardly conceivable without an alignment of national interests amongst relevant regional players like Russia and Iran. While most short-term and medium-term goals of the peace process (the return of refugees and internally displaced persons and the end of hostilities) have been met, the erosion of institutionalised power-sharing mechanisms has greatly undermined the post-civil war status quo. With the structural tensions behind the war still unresolved, the only major stabilising force in Tajikistan is the considerable self-restraint of stakeholders, primarily of the opposition, which partly accounts for the IRPT’s passivity all the way until the recent government crackdown. All in all, post-civil war political developments in Tajikistan show a considerable degree of path-dependency, with wartime experiences and the peace process still determining political outcomes to a large extent. However, while this still holds true of the ruling elites, an increasing percentage of the population with no recollection of past hostilities would be less reluctant to refrain from violent contestation.

Notes

The conflict pitted regionally-based interest groups against one another in a struggle both for access to state resources and over competing ideological visions for the country’s future. The pro-government factions, drawn from the ranks of the Soviet-era bureaucratic elite and backed by the traditionally dominant lowland-dwelling Tajikistanis in the north and south of the country, were bent on defending the post-independence status quo. Independence had been thrust upon the Central Asian republics unexpectedly in 1991. Tajikistan’s political leadership, having with great reluctance shouldered their emancipation from Moscow, aimed to mitigate for these changes by preserving a degree of continuity with the Soviet era. This meant maintaining strong state control over the lives of the country’s citizens, especially in the economic, religious and national identity realms.

The chief challenger of the status quo was the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), a loose coalition of Tajik nationalists, moderate Islamists, liberal democratic activists and advocates for greater self-determination for the linguistically and confessionally distinct Gorno-Badakhshan region. The Tajik opposition’s aims were the relinquishment of Tajikistan’s Soviet legacy and a partial reorientation of the country’s political ties from the post-Soviet space towards the wider Persian-speaking world. The UTO was backed by the inhabitants of the rugged mountainous regions of central and eastern Tajikistan, by their regional-identity-preserving kinsmen in the cotton-rich southern lowland Qurghonteppa region, relocated there by force during the Stalinist era, and also by the liberal-minded parts of the urban intelligentsia.

The armed conflict was the culmination of a series of domestic crises, starting with the February 1990 riots (triggered by the rumoured relocation of Armenian refugees to Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital). Large-scale opposition protests in mid-1991, in reaction to the failed coup in Moscow, culminated in the resignation of then President Mahkamov and the outlawing of the Communist party. The emboldened opposition took to the streets again the following year, after the dismissal of the Badakhshani minister of interior Navzhuvanov.4 Firearms found their way into the hands of the participants of opposing rallies and town square sit-ins and violence eventually broke out. The fighting then spread to most parts of the country, as returning protesters and counter-protesters alike brought belligerent zeal to their own respective home provinces. The first months of the war were also the most violent. A pro-government paramilitary group known as the Popular Front initiated “sub-ethnic” cleansing, singling-out civilians on the basis of on their regional origins, first in the mixed Qurghonteppa region, only to bring this tactic over later to the capital. Tajikistan’s neighbours and other regional powers played an important role in both the civil war and the eventual peace talks. The government received fluctuating degrees of support from the Russian Federation and neighbouring Uzbekistan, while Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance5 supplied the UTO with arms, training and logistical support. As for Iran, it provided the opposition with ideological backing, most notably supporting the now-banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), the UTO’s most powerful constituent.

The article maps the peace process and post-war power-sharing in Tajikistan. It shows how the post-conflict political order unravelled, with the creeping monopolization of the executive branch by pro-government forces squeezing out all meaningful opposition. Nevertheless, despite the political and economic challenges and persistent regional divisions, no renewed larger-scale armed conflict has taken place in Tajikistan so far.6

The conflict pitted regionally-based interest groups against one another in a struggle both for access to state resources and over competing ideological visions for the country’s future. The pro-government factions, drawn from the ranks of the Soviet-era bureaucratic elite and backed by the traditionally dominant lowland-dwelling Tajikistanis in the north and south of the country, were bent on defending the post-independence status quo. Independence had been thrust upon the Central Asian republics unexpectedly in 1991. Tajikistan’s political leadership, having with great reluctance shouldered their emancipation from Moscow, aimed to mitigate for these changes by preserving a degree of continuity with the Soviet era. This meant maintaining strong state control over the lives of the country’s citizens, especially in the economic, religious and national identity realms.

The chief challenger of the status quo was the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), a loose coalition of Tajik nationalists, moderate Islamists, liberal democratic activists and advocates for greater self-determination for the linguistically and confessionally distinct Gorno-Badakhshan region. The Tajik opposition’s aims were the relinquishment of Tajikistan’s Soviet legacy and a partial reorientation of the country’s political ties from the post-Soviet space towards the wider Persian-speaking world. The UTO was backed by the inhabitants of the rugged mountainous regions of central and eastern Tajikistan, by their regional-identity-preserving kinsmen in the cotton-rich southern lowland Qurghonteppa region, relocated there by force during the Stalinist era, and also by the liberal-minded parts of the urban intelligentsia.

The armed conflict was the culmination of a series of domestic crises, starting with the February 1990 riots (triggered by the rumoured relocation of Armenian refugees to Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital). Large-scale opposition protests in mid-1991, in reaction to the failed coup in Moscow, culminated in the resignation of then President Mahkamov and the outlawing of the Communist party. The emboldened opposition took to the streets again the following year, after the dismissal of the Badakhshani minister of interior Navzhuvanov.4 Firearms found their way into the hands of the participants of opposing rallies and town square sit-ins and violence eventually broke out. The fighting then spread to most parts of the country, as returning protesters and counter-protesters alike brought belligerent zeal to their own respective home provinces. The first months of the war were also the most violent. A pro-government paramilitary group known as the Popular Front initiated “sub-ethnic” cleansing, singling-out civilians on the basis of on their regional origins, first in the mixed Qurghonteppa region, only to bring this tactic over later to the capital. Tajikistan’s neighbours and other regional powers played an important role in both the civil war and the eventual peace talks. The government received fluctuating degrees of support from the Russian Federation and neighbouring Uzbekistan, while Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance5 supplied the UTO with arms, training and logistical support. As for Iran, it provided the opposition with ideological backing, most notably supporting the now-banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), the UTO’s most powerful constituent.

The article maps the peace process and post-war power-sharing in Tajikistan. It shows how the post-conflict political order unravelled, with the creeping monopolization of the executive branch by pro-government forces squeezing out all meaningful opposition. Nevertheless, despite the political and economic challenges and persistent regional divisions, no renewed larger-scale armed conflict has taken place in Tajikistan so far.6